It would be hard to overestimate the impact of ‘The Jungle,’ Upton Sinclair’s 1905 novel exposing the meat-packing industry. First published as a serial in the Socialist ‘Appeal to Reason’, its influence in the workers’ movement, law, journalism, and public perceptions of business were profound. Left wing literary critic Floyd Dell writes on its significance and many repercussions.

‘The Aftermath of ‘The Jungle’’ by Floyd Dell from the Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 4 No. February 12, 1927.

IN 1905 there began to appear, in a socialist weekly, the Appeal to Reason, published in Girard, Kansas, a novel of the Chicago stockyards, by an almost altogether unknown writer: The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair. I can remember, as a boy of eighteen, reading in my Appeal that first chapter describing the wedding party of Jurgis and Ona, and my delight in the rich, full-blooded humanity of that scene. It was the happy prelude to what was to be, as week after week the story unrolled itself, a tragic panorama of working-class life, true, terrible, and magnificent.

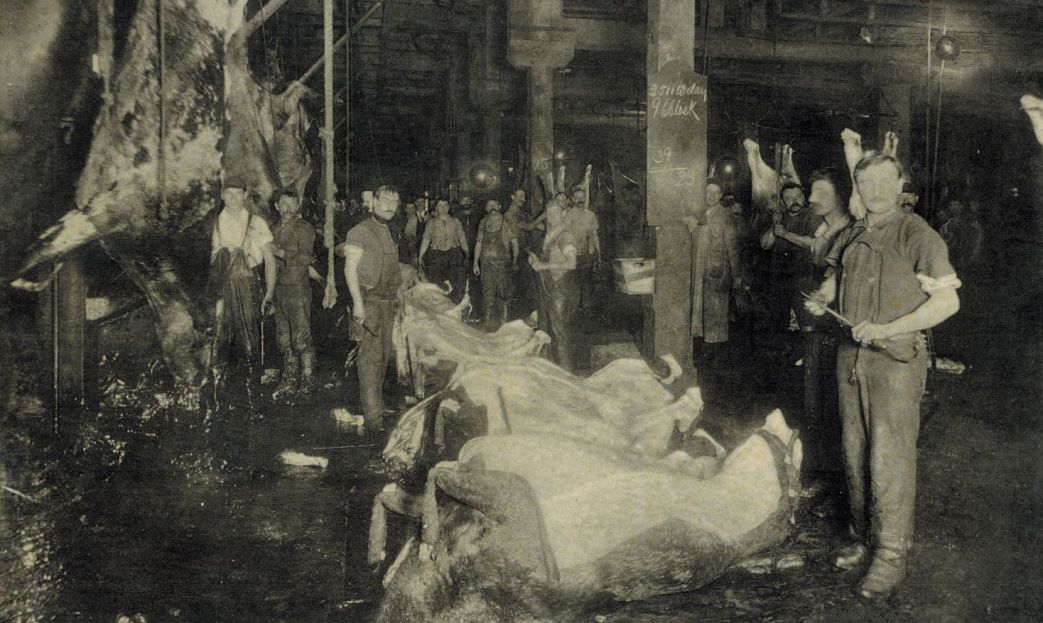

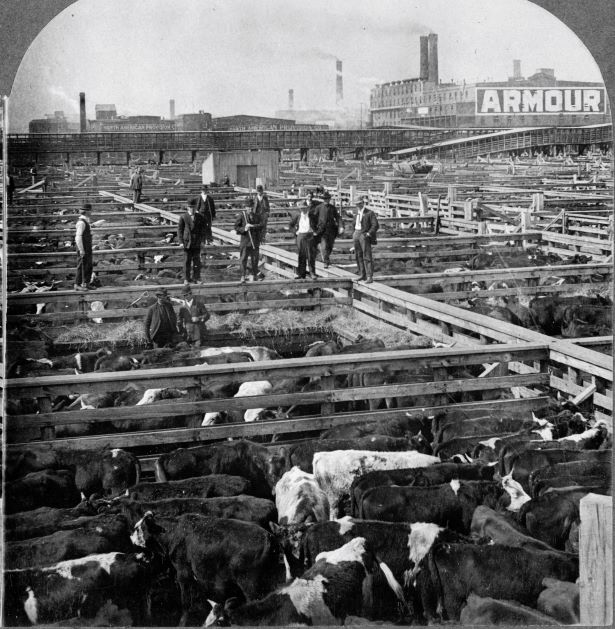

The story was simple enough; it related the for- tunes of a group of immigrants who lived and worked in the stockyards district–their struggle to get ahead, to own a home, to bring up their children decently, while all the time they are brutally exploited, preyed upon, robbed, outraged, by the unscrupulous forces which find in their poverty and ignorance and helplessness more opportunities for enrichment. The group is crushed, one by one, in the struggle; old men are thrown on the scrap-heap to starve, the women are drawn into prostitution to keep body and soul together, the children die; Jurgis himself goes to prison for smashing the face of a brutal boss, and when he comes out his little world had been destroyed as if by an earthquake–and he is left to wander, getting wisdom as he wanders, and coming at last to believe in a socialist reconstruction of this hideous world. At every point the story is enriched by the most vivid and relentless realistic detail; one is immersed in the filth and stench and cruelty of the stockyards, and one feels the sublime human aspirations which even there burn unquenchably in humble hearts.

For a while the knowledge that a great new novelist had appeared in America was almost confined to the readers of that socialist weekly–no small audience, however, for the “Appeal army” of enthusiastic subscription-getters had drummed up half a million readers for that publication. The first public, therefore, of this astonishing novel, was of farmers resting in stocking feet beside the stove of winter evenings, and of discontented workingmen in a thousand cities and towns–an audience which, whether rural or urban, understood the truths of human suffering which it so vividly portrayed. That was its first success–its recognition and acclaim by a proletarian audience. Then came recognition by fellow-writers, who heard of this strange and powerful novel being published in a socialist weekly, and sent for back numbers. David Graham Phillips wrote to the author: “I never expected to read a serial. I am reading “The Jungle” and I should be afraid to trust myself to tell how it affects me. It is a great work. I have a feeling that you your- self will be dazed someday by the excitement about it. It is impossible that such a power should not be felt. It is so simple, so true, so tragic, and so human. It is so eloquent, and yet so exact.” And, of course, Jack London, his comrade in the socialist movement, did not fail to acclaim this achievement. “The Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery,” he called it; and with that legend on the jacket and in the advertisements it was brought before the general American public in book form in 1906. It was an immediate and enormous success. It became a “bestseller” in America, England and the British colonies. It was translated into seventeen languages, and the world became aware that industrial America in its toil, its misery and its hope had found voice.

2.

But the literary sensation in America had already become secondary to the shock of its readers in learning of the conditions under which their meats were prepared in Packington, not as affecting the workers but as affecting their own health–for the story dealt incidentally with the use of condemned meat. The author later remarked that he had aimed at the public’s heart and by accident had hit it in the stomach. His deepest concern had been with the fate of the workers, and he realized with bitter- ness that he had become a celebrity not because the public cared anything about the workers but because it did not want to eat diseased meat.

The public was more or less prepared for such charges against the packers, on account of the “embalmed beef” scandal during the Spanish-American war. President Roosevelt, responding to a widespread popular demand, sent a commission to Chicago to make an investigation of conditions in Packingtown. This commission was assisted, at Mr. Sinclair’s expense, by Ella Reeves Bloor, who had been familiar with conditions there and had helped him in his seven weeks’ investigation preliminary to the writing of the novel; and the researches of this commission appear to have confirmed the chief charges made in the book.

The young novelist accepted, as a socialist, the opportunity which this situation provided for agitation. But the packers, and large business interests in general, were aroused, and all their power and influence was used to keep this agitation from reaching the public, and to represent the young agitator as an irresponsible sensation-monger. He set up a publicity bureau, worked twenty hours a day, wrote articles, sent telegrams, and gave interviews to roomfuls of reporters; but so thoroughly had the newspapers been mobilized by the business interests as a medium of defense that the publicity he actually achieved for the workers’ cause was slight; and on the other hand, his own reputation, in genteel literary and critical circles, and among the public at large, was seriously damaged. In the course of these efforts, President Roosevelt said to him: “Mr. Sinclair, I have been in public life longer than you, and I will give you this bit of advice; if you pay any attention to what the newspapers say about you, you will have an unhappy time.” He might have taken this as a warning that his temperament was not suited to public life, for he could not get used to being lied about in the newspapers; but he persisted in his efforts, and he did have a very “unhappy time.”

Nothing in particular was done about the workers’ conditions. Even the president’s meat-inspection law, as finally passed, had, in the opinion of those behind it, had all its teeth drawn first. Sinclair continued his attempt to agitate the question, but the public had been reassured, and the effort was futile. In The Brass Check, where the complete story of this period is told vividly, he says: “I look back upon this campaign, to which I gave three years of brain and soul sweat, and ask what I really accomplished.” He had taken, he says, a few million dollars away from the Chicago packers, “giving them to the Junkers of East Prussia, and to the Paris bankers who were backing enterprises to pack meat in the Argentine.” He had added a hundred thousand readers to the circulation of a popular magazine, which speedily repudiated its early muck-raking habits and became a defender of big business. And he has made a fortune for his publishers, who immediately became conservative and devoted their profits from “The Jungle” to promote a kind of writing hostile to everything in which he believed.

3.

“The Jungle” was in fact the climax of a literary movement in America which had aroused the fear and anger of large business interests. The great middle-class reform movement, marked in the political field by the careers of Bryan, Roosevelt and the earlier Wilson, had produced an audience sympathetic to the telling of unpleasant truths about American political and business conditions. In the magazine field this was called “muck-raking”; there were sensational revelations of the inside workings of Wall street by Tom Lawson, of municipal corruption by Lincoln Steffens, of Standard Oil history by Ida M. Tarbell, of Beef Trust finance by Ray Stannard Baker. In the fictional field there was a corresponding literature, written by such men as Robert Herrick, Frank Norris and David Graham Phillips. This literature had its social revolutionary fringe; Jack London was an avowed revolutionist, and such socialist critics of society as W.J. Ghent, John Spargo, Robert Hunter, Charles Edward Russell and William English Walling, had a wide hearing. A professor named Thorstein Veblen had written a devastating book called “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” and phrases from it had passed into general intellectual currency. These conditions were sufficiently alarming, in a country where every year, in one great industry or another, there was a bitter struggle between employers and men, in which bullets were the decisive factor. And now a young man, by writing a book, had put a great industry on the defensive before the whole public. It was necessary to tighten the grip of business upon the intellectual world. The newspapers were already well in hand; but there was a group of free magazines which were making money out of “muck-raking”-the very center of the intellectual rebellion. Big business struck at this group of free magazines, effectively, through the medium of advertising. The magazine policies were changed. Writers were called off from investigations of industrial conditions. An immense campaign of optimism was begun, and a cheerful outlook upon American industrial conditions was preached and made synonymous with patriotism. The writers for the most part changed with the times, and adapted their views to the new editorial demand; the others were silenced or discouraged. A few prominent radical journalists, unable to tell the truth any longer in the magazines, bought one of their own; but they, too, presently succumbed to the spirit of the times. Sinclair quotes, in “The Brass Check,” the titles of some representative articles from a recent issue of that once-daring magazine: “How We Decide When To Raise a Man’s Salary,” “The Comic Side of Trouble,” “Interesting People: A Wonderful Young Private Secretary,” “From Prize- Fighter To Parson.”

The public, deprived of the intellectual stimulant of unpleasant truth before it had quite got used to it, was easily trained in more cheerful tastes. Those writers who sought to revive the art of muck-raking found themselves with an indifferent audience. “People aren’t interested in that sort of thing anymore.” While as for fiction, the old genteel tradition reasserted itself, the standard of non-controversiality became identical with the standard of decency, and any author who dared to violate this standard ran the risk of finding himself removed in critical esteem beyond the pale of literary respectability.

The measure of the wrath of the masters of America and the docility of its intellectual class during this period may be taken from the Gorky incident, which happened in the spring of 1906, coincident with the Jungle agitation. The great Russian novelist, Maxim Gorky, had come to America to raise funds for the cause of Russian freedom–a cause long since made popular among even the respectable American intelligentsia by the writings of the American journalist, George Kennan. A great welcome was prepared for him. But it happened that two radical union leaders, Moyer and Haywood, were on trial for their lives in a western state in the course of an industrial war between the miners and the coal barons. Their cause had been espoused by the socialists, who now asked Gorky to sign a telegram of sympathy to Moyer and Haywood. He did so. A White House reception to Gorky was immediately canceled. And then the American papers, at the instance of the Czarist embassy, began to denounce Gorky, on the pretext that he had “insulted” the American people by bringing with him as his wife a woman to whom he was not married. It was known to those who made the charge that Russian revolutionists married without the churchly processes which alone were “legal” in Russia, and that Madame Andreieva was his wife according to the revolutionary code; they had known that all along, and had not made use of the fact. Now they unloosed upon him the furies of a hypocritical moralistic journalism. He was hounded out of New York hotels, denounced in every pulpit and newspaper in the country; his mission was destroyed. And the American men of letters who had been proud to be invited to dine with this Russian giant, were afraid to brave that storm; one and all, the respectable writers turned tail and fled, not daring to call their souls their own-a black day in the calendar of American letters. Great reputations fell that day, Mark Twain’s among them, in the minds of boys and girls, now grown up, who saw that humiliating and cowardly action with the clear eyes of youth and were ashamed for their country. If American literature is now less timid about sex, that young indignation may have something to do with it. But those boys and girls did not know why America and American men of letters had suddenly become so prudish: they did not know that Maxim Gorky’s influence had been destroyed in that sudden journalistic whirlwind, not because of the lack of churchly blessings upon his union with Madame Andrieva, but because he had rashly intruded into an American economic struggle on the unfashionable side. He, and the writers of America, must be taught a lesson, and made to realize who was running this country and what happened to anybody who tried to interfere with them.

The stage of Upton Sinclair’s literary career, immediately ensuing upon his immense celebrity as author of The Jungle, falls within this period when “muck-raking” was being outlawed and editors and writers taught a lesson by those in control of American business. He was one of the few who dared to brave this Thermidorian reaction, and he was chief of those to suffer from it. It is his temerity which explains the fact that his reputation in America as a novelist fell during that period to zero, or lower. He missed, by remaining a “muck-raker,” his chance of regaining literary respectability. His next novel, The Metropolis, published in 1907, was an attack on New York society; and The Money-changers, published in 1908, was an exposé of Wall Street. Nor is this explanation to be discounted by the fact that The Metropolis and The Money-changers were not very good novels.

The point is worth laboring. Novels far inferior had been of a different tendency; not to realize that is to be ignorant of American criticism and Sinclair, and to accept the yellow-journal pictures its fashions. It was the fashion to sneer at Upton of him, in which he was represented as a mere sensation-monger and a fool to boot.

George Brandes, generally accounted the world’s greatest modern critic, was astonished at this American neglect of one of its greatest writers; on visiting this country in 1914, he took pains to say to the reporters who met him at the steamer that there were three American novelists whom he found worth reading, one of these being Upton Sinclair. The statement, as it generally appeared in the press, referred only to Frank Norris and Jack London, omitting Upton Sinclair’s name altogether. Doubtless it was naively regarded as incredible that anyone should really take this disreputable “muck-raker” seriously…And it was not until a new rebellious literature and criticism emerged after the war, under the leadership of Sinclair Lewis and H. L. Mencken, that Upton Sinclair was again mentioned among American writers by any reputable native critic, who was not a Socialist.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1927/1927-ny/v04-n026-new-magazine-feb-12-1927-DW-LOC.pdf