The speech of the head of the Red International of Labor Unions on the discussion of the colonial revolution at the Sixth Comintern Congress in 1928 takes up the notion of ‘decolonization’ debated at the time, and the limits of categorization when contemplating policy.

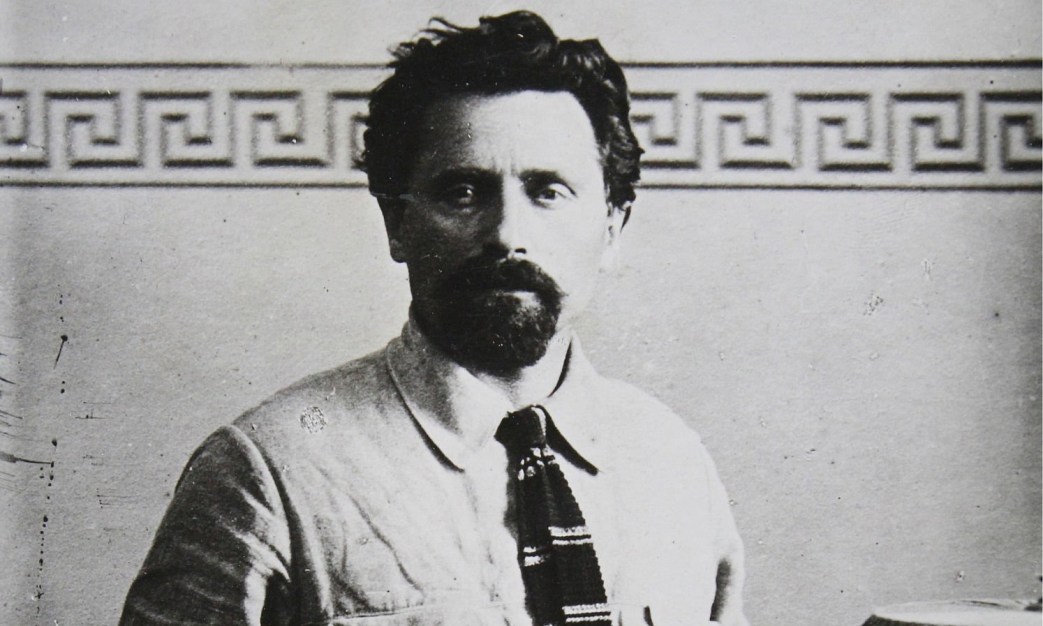

‘The Theory of Decolonisation and the Industrial Development of Colonies’ by Alexander Lozovsky from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 8 No. 76. October 30, 1928.

Comrades, the colonial question occupies an important place in the theory and practice of the Comintern. Therefore, detailed discussion of all the questions connected with this question, on the one hand, and the discussion of the concrete situation in which the struggle has to be carried on, on the other hand, is the premise for laying down a correct Bolshevik line for colonial Parties, Parties in capitalist countries and for the whole Comintern.

Over two-thirds of mankind have a colonial status. One has to reckon with an exceptional diversity of countries, races, political and social-economic systems, and therefore the most important and absolutely necessary task is concretisation and study of questions and problems which concern this or that country. If we speak of China as a semi-colony, and of India as a colony, if we speak about Egypt and at the same time mention also Mexico or Chile and Colombia, it is very difficult to bring all these countries under the same heading. Every separate country represents a complex of very intricate phenomena; colonies differ as much from one another as capitalist countries. The attempts to pigeon-hole all the colonies according to types, are not very successful. One should ask oneself the question: what makes the colonial question different now from what it was in 1920, when Lenin’s theses on the colonial question were adopted by the II. Congress of the Comintern. What change has taken place in these 8 years?

The following change has taken place: during this period, in a number of colonial and semi-colonial countries there has come onto the historical arena the proletariat as the main force of the revolutionary struggle. This was not yet the case in 1920. At that time the proletariat did not yet come forward as an independent revolutionary factor, as the main force in the struggle for independence. That is why we can and must already speak now about the dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry, and about the leading role of the proletariat in the national struggle. I think that this new element must put its mark on all the theses and the tactic of the Comintern in regard to this or that colony.

However, the advent of the proletariat as a serious, decisive revolutionary factor, at least in some countries as for instance, China, India and others, the advent of proletarian organisations, is linked up with a certain capitalist development of these countries, a development which is forced into imperialist moulds, which is to a considerable extent distorted and which is pursuing an excessively meandering and painful path as far as the masses are concerned. Nevertheless there is a certain amount of industrialisation and in connection with it the advent of a compact proletarian mass capable of carrying on an organised struggle against imperialism and the native bourgeoisie.

One cannot of course make from this the deduction which was made in the press concerning the decolonisation of the colonies. I think that this theory of the decolonisation of the colonies has no foundation whatever. A few formal signs, a change in the forms and methods of exploitation are taken as a substantial change in the relations between imperialism and the colonies. Decolonisation is possible only after the victory of the revolution in corresponding colonial countries, as a result of a prolonged struggle of the proletarian and peasant masses effectively supported by the International Communist movement in the shape of the Comintern and by the Communist Parties of the biggest imperialist powers. To speak of peaceful decolonisation, means begging the question, it means, instead of elaborating tactics adaptable to new conditions, circumstances, methods and means of enslaving colonial countries, trying to get off with abstract formulae instead of concrete revolutionary tasks, because the decolonisation theses does away with the whole question of struggle for national independence. Since the entire decolonisation takes place automatically, by means of the further development of capitalist relations, it is but natural that the national-revolutionary movement becomes unnecessary. That is why it seems to me that the theses are quite right in opposing this theory and in emphasising its non Communist character.

But this certainly does not mean that nothing has changed in the colonies. We witness there a number of facts which compel us to watch carefully the new forces which have made their appearance on the historical arena, to study thoroughly the new phenomena which are cautiously mentioned in the be- ginning of the theses in the casual phrase about “the reinforcement of the elements of capitalist and especially industrial development”. It seems to me that this caution is out of place. We can speak more definitely about the industrial development of some colonial countries, especially China, India, etc. But just because, even according to the theses, we witness a “reinforcement of industrial development” in some colonies, it is wrong to describe all colonies as “hinterland”, as “agrarian rear”, because this is not true to facts.

We witness two phenomena in a number of colonies:

1. Penetration of capitalism into agriculture (gigantic sugar, cotton and rubber plantations in Cuba, Africa, Indonesia, etc.).

2. Growth of extracting (oil, minerals, etc.) and manufacturing (textile, etc.) industry and growth of transport (water transport, railways). Agrarian rear is one thing and raw material rear (cotton, rubber, minerals, oil, etc.) and the existence of a manufacturing industry is another. The creation of raw material bases in the colonies and in connection with accentuated competition every imperialist power creates its own cotton, rubber, oil and mineral base (Japan and Korea) contradicts the theory of a solid “agrarian rear”, the theory of the “hinterland”, the theory of the “continent of rural districts”. If we speak of India as a “continent of rural districts” and of all colonies as “world rural districts”, as this is done in the programme without sufficient justification, all talk about proletarian and peasant dictatorship must cease automatically. In the “world rural districts”, in the “continent of rural districts”, there can be no industrial proletariat, and therefore no room for proletarian and peasant dictatorship. With such terminology the proletariat disappears as leader. And yet, when we speak of proletarian and peasant dictatorship, we evidently assume the existence of a definitely constituted proletarian mass the bearer of the presupposed hegemony. This bearer of hegemony could come into being only on the basis of the development be it only a slow, meandering and very painful development of capitalist relations in the colonies. That is why all these political slogans which are correctly issued for colonies of the first type (China, India, etc.), slogans of proletarian and peasant dictatorship, do not tally with the preliminary description of all these countries as “continents of rural districts”, as “world rural districts”, as the one and only “agrarian hinterland”. By insisting on these slogans, we leave no room for phenomena which are indisputable, which are reflected in the struggle of the Chinese and Indian proletariat, in the struggle which has become possible in the last years owing to the development of capitalism in the colonial and semi-colonial countries. That is why it seems to me that this part of the theses will have to be carefully revised, so as to vary the description of these countries and not to apply a terminology which will make it difficult subsequently to arrive at correct political conclusions. We must in this respect bring into harmony the beginning, middle, and end of the theses. To use poetical language, such harmony is conspicuous by its absence.

Artificiality in the Classification of Colonies.

The second group of questions to which I would like to draw your attention is the classification of all colonial countries given in the theses. I must say that classification in general is necessary and useful but the classification placed before us, in spite of its undisputed conscientiousness, shows that an utterly impossible task has been set, and as you know, it is rather difficult to carry out impossible tasks…

Let us take these four types of countries. According to the classification we find in the first group China and India together with Indonesia, Egypt, Syria (!) as well as several Latin American colonies. In the second group we find South Africa, and Cuba, and in addition, Algiers, Tunis, etc. I have been asking myself what peculiarities have led to this classification? It appears that the classification rests on “the peculiarity and degree of development of the class differentiation”. The degree of development of class differentiation, means, translated from the social-political into the economic language, degree of development of capitalist relations in the given country (numerical strength of the proletariat, degree of industrial development, etc.). But the next paragraph gives also other characteristics for classification. This additional characteristic is: “importance of colonies and semi-colonies in the present system of the colonial policy of world capitalism”. But these two signs or characteristics are not brought into harmony. If we take as the basis the latter point, we get of course one classification. If we take the first point, i.e. “peculiarity and degree of class differentiation”, we get an utterly different classification. But as both characteristics are taken, the result is a considerable muddle. Why is Syria in the same group as India and China, whereas the Philippines and Cuba are not in it? If we read this classification very carefully and I suppose that everyone of us has read all the theses very carefully we find that it suffers from a certain artificiality. However, it would not be so bad if there were only a certain artificiality in the construction, unfortunately political deductions are made from this construction concerning our policy in the corresponding type of country. This classification or these barriers erected among the colonies, must determine our tactic. This is the crux of the matter. Well, if this is so and according to the theses it is so the question of classification acquires an enormous importance. If we take the theses, we see that the united national front, proletarian and peasant dictatorship, etc., are made to depend on the type under which a given country is classified. It was the intention of the author of the theses to facilitate for us by classification the elaboration of tactics, but instead of this classification has made this process more complicated. I personally think that this classification is artificial because it is based on principles of diverse character. It is difficult to carry this classification to a conclusion, it is difficult to make from it political deductions in as far as cording to the diverse characteristics by which the countries have been classified one has to make the same political deductions for colonies with a different development, different social relations, different class differentiation and a different economic system.

The Bourgeois Democratic Revolution.

Very naturally the bourgeois democratic revolution occupies much space in the theses. One must say that our Communists from the colonial and semi-colonial countries and Communists in countries which are not yet colonies but will soon become colonies (Latin America), are rather suspicious of the terminology “bourgeois-democratic revolution”. It seems them that to describe the revolution as bourgeois-democratic diminishes the role of the Communist Party. “How is the Communist Party to play a leading role in the bourgeois-democratic revolution?” asked many comrades. Hence the deduction that the Communist Party must be for the Socialist Revolution at all times and under any circumstances and cannot descent to the bourgeois-democratic revolution. Hence, the attempts to call a purely bourgeois revolution a Socialist Revolution (Ecuador). It must be made quite clear that an exact definition of the class-character of the revolution is the premise of a correct tactic. This failure to understand is not only a characteristic of the representatives of colonial countries, it was also a characteristic of many of our comrades in certain periods of the history of Russia. This lack of understanding must be avoided.

After all, what does bourgeois-democratic revolution mean, and how did Lenin, and with him the Bolshevik Party, understand it?

We have on this subject a wealth of literature and experience. If you turn back your mind to 1905, when this problem loomed big and when the dispute between Bolshevism and Menshevism went for the first time beyond the limits of organisational questions and got into the sphere of fundamental problems confronting the working class of Russia if you remember the struggle at that time, you are aware what is was about. From the estimate of the revolution as a bourgeois-democratic revolution, the Mensheviks arrived at the conclusion that the bourgeoisie must play a leading role in the revolution. From the same estimate the Bolsheviks arrived at a different conclusion: although the revolution is bourgeois-democratic, the leading role in it must rest with the proletariat and its Party, and only the proletariat, together with the peasantry can lead a real democratic revolution to a conclusion against the bourgeoisie. This is how Bolshevism put this question. This is how this question must be put for the whole Comintern and especially for the Communist Parties of the colonial countries. This must be told to those of our Parties which are considering revolutionary problems for the first time. It must be explained to the Communist and non-Communist masses what bourgeois-democratic revolution in the Bolshevik sense means, and what must be the tactic of the Party in this kind of revolution.

Moreover, it is absolutely necessary to give an answer to the question “what is dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry?” The slogan “dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry” has also its own history. This slogan has been our political device for many years. We owe to Lenin its most clear and most Marxist elaboration. He has explained what bourgeois-democratic revolution and dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry mean. On the basis of this experience the Comintern must say what bourgeois-democratic revolution is, what shapes and forms it takes, what the proletariat must do in this revolution when, together with the peasantry, it establishes dictatorship, what our desire should be also after the establishment of proletarian and peasant dictatorship. Unfortunately, we do not find an answer to this in the theses, and this is a very serious gap. We must bear in mind that this is the first time that the Comintern wants to give an exhaustive answer to all the fundamental problems which confront the revolutionary, colonial and semi-colonial labour movement. The general principles have been laid down by Lenin; but under new circumstances and a new correlation of class forces, in view of the birth of new mass revolutionary movements, in view of a new distribution of forces, we have to give an answer to these extremely complicated questions, we must explain all this as clearly and simply as possible so that every worker, especially every Communist worker, could understand, because he will have to act up to it wherever he is.

The Leading Role of the Proletariat and its Party.

In this connection of the utmost importance to the Comintern is the question of the form and expression of the leading role of the Communist Parties. This is laid down in the theses because this is our policy. The proletariat must have hegemony in the revolution and in the entire national-revolutionary movement. Well and good, the Communist Parties must lead the proletariat. This is a matter of course. But what does all this mean concretely, practically? How is this to be achieved, what does it mean for every separate country these questions must be answered. The general formula is the canvas. The patterns must be selected according to countries because the colonial world is so diverse that one cannot possibly compress all this into one general formula. In spite of the thorough elaboration of the theses and the evident desire to lay down concrete lines, we have not succeeded in doing this because conditions are too diverse to compress all this into four types, into a rigid and to a certain extent immovable framework.

Here generalisation must make room for specification. The theses go from the general to the particular. The reverse should be the case. The tasks confronting the proletariat of China, India, Indonesia, Egypt and the Philippines are the same in the sense that the workers of all these colonies must struggle for their national and social liberation. But this general standpoint is clear even without the theses. Our task consists in telling every proletariat, on the basis of a thorough study of the state of affairs and of the correlation of forces in the given country, what and how one should do now. While in China the leading role of the Party has already been secured it is true at a heavy price and has stood the test, in other colonial countries mass Parties are still to be created. Under such circumstances one should say first of all how a fighting mass Party is to be created, otherwise there will be talk about proletarian hegemony and the leading role of the Party whereas the Party is still in embryo. It is self-evident that in this respect one cannot limit oneself to a general formula; one must lay down concretely the lines and methods for the establishment of a labour movement independent of the national bourgeoisie and of fighting Communist Parties.

Two Phases and Three Stages.

The next group of questions which, it seems to me, are also not sufficiently clear and require elaboration (Comrades, I am mentioning here only matters which are not clear), are all the chapters which lay down the various phases and stages of the bourgeois-democratic revolution. There are four types of countries, two phases and several stages. Such a scheme is too complicated. For an average Communist all this must be considerably simplified.

There is much that is valuable in the part which deals with phases and stages: I personally read with the greatest interest and attention all these considerations, but they are too abstract. We do not write theses for ourselves, neither do we write them only for the European Communists; we write them also for the colonial workers, and maximum simplicity is absolutely necessary because otherwise a whole series of annoying political errors might arise. If we establish for several types of countries several phases of bourgeois-democratic revolutions and want at the same time to say what will happen when the given revolution will go from one stage to the other, we will inevitably get a scheme which it will be difficult to unravel. We do meet, for instance, with such terminology in the theses: “From the first phase to the end of the first stage”, “embryonic genesis of proletarian hegemony”, “third stage of the bourgeois- democratic revolution”. I want you to think a minute: four types of countries, two phases, in each phase three stages, and in addition to this “a preliminary phase”, “preliminary phase of the first stage”, “unfinished first stage of the first phase”, “preliminary situation of the second phase”, etc. All this sounds very well, but it is a bare scheme accessible only to a few people. Such an abstract structure can only confuse our Parties. For this reason, I think that this part of the theses should be revised.

The Proletariat and the Bourgeoisie in the Colonial Countries.

The question of relations between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in colonial countries deserves all our attention. This question is dealt with in the theses from two viewpoints theoretical and the practical, applicable to India. Inasfar as theory is concerned, the theses say correctly that not only support, but also agreement with the colonial bourgeoisie is Possible for struggle against imperialism. The proletariat and its Communist Party must support the national-revolutionary movement, they must develop, widen and intensify and carry it further. But, comrades, if a correct standpoint is mechanically transferred to India without studying concrete conditions and class forces, the evolution of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in the last years, etc., this is bound to lead to erroneous tactical conclusions. One should have first taken the country where such an experience has been gone through, one should have studied this experience, and only then one should have transferred to India what is suitable for it. It seems to me that one should take China and find out what this tactic has produced, pointing out the difficulties which arose in its application and making a study of all the mistakes which were committed (this is done, but not in this connection), and then make deductions: has the tactical line stood or not stood the test when it came face to face with practice. I think that our general line has certainly stood the test, in spite of the mistakes which were made. If we had begun with China and had then gone to India, we would have taught the Indian proletariat not to make the mistakes which were made in China. This is one thing, but it is not all by far. Is it possible to draw a simple analogy between our policy in China and India? Inasfar as these two countries are placed into one group, the same tactic is presupposed for them. This is not only wrong, but dangerous. Other circumstances, other correlation of classes.

What is said after all in the theses about our tactic in regard to the Indian bourgeoisie?

“It would be an ultra-Left mistake if the Communist Party began its agitation by simply placing on par the national-reformists (Swarajists, Wafdists, etc.) and the ruling countr-revolutionary bloc of the imperialists and feudal lords. The Swarajists have not yet betrayed the national-liberation struggle as this has been done in China by the Kuomintang, although they have capitulated ignominiously in certain cases before the imperialists and have even participated in the suppression of revolutionary and semi-revolutionary actions of the workers. In this phase, Communists must concentrate the main fire not against them, not against the national bourgeoisie, but against the present chief enemy, the ruling imperialist-feudal bloc”.

In this paragraph the tasks of the Indian Communists are not laid down correctly. First of all, what makes it necessary to wait with our struggle against the Indian bourgeoisie till it turns traitor like the Kuomintang, i.e. till it begins to hang and shoot thousands and tens of thousands of workers and peasants? Moreover, one cannot lay down the tasks of the Indian proletariat only from the viewpoint of external policy (struggle for independence). The Indian proletariat has as important tasks also in the sphere of internal policy: agrarian revolution, 8-hour day, etc. What constituted the fundamental error of the Chinese Communist Party in the period of the bloc with the Kuomintang? It was this: the Chinese Communist Party subordinated the social-economic demands of the workers and peasants (land, eight-hour day, etc.) to the struggle for national independence. In the meantime the Comintern has never visualised this bloc as relinquishment, renunciation on the part of the working class of its and the peasants’ immediate economic demands. This applies also to India. The Communist Party of India must define its tactic in regard to the national bourgeoisie not on the basis of the latter’s phraseology about Indian independence, but on the basis of its entire internal and external policy, and this policy is directed against the labour and peasant movement. This is the main thing; all the rest is empty phraseology.

Moreover, is the centre of gravity for India coquetting with Left tendencies for the sake of relations with the Swarajists? Is the main question for India: to support or not to support the Swarajist bourgeoisie? Certainly not. If we compare the Indian bourgeoisie with the Chinese, we will find that in India the bourgeoisie is stronger, better welded together and better educated politically than in China. In India the correlation of class forces is different from that in China. We have in India a national bourgeoisie which is always ready for compromise with the British bourgeoisie against the toiling masses. Therefore, in India our main task is establishment of independent labour organisations. It is essential to create, organise and educate politically an independent labour movement, independent of the Swarajists. It is essential to establish independent trade unions, a base for the labour movement. This central idea gets lost in the discussions “about the chief firing line” and about the possibility of supporting the Swarajist bourgeoisie under certain circumstances. I think that this is politically incorrect. We must say in regard to India, especially in the present stage of development: If you really want to achieve something in India, establish as rapidly as possible a Communist Party and trade unions, get away the labour movement from Swarajist influence, eliminate national-bourgeois elements from the labour and peasant organisations, otherwise all these mass organisations will get into bourgeois hands and will be used for counter-revolutionary purposes. This is the centre of gravity of the question, but this is not expressed with sufficient clarity.

The Labour Movement in the Colonies.

These theses are called: The revolutionary movement in colonial and semi-colonial countries. The revolutionary movement must be carried on in the industrially more developed countries under the hegemony of the proletariat. But it would seem that those who exercise hegemony should also be given a place in these theses, i.e. those who will lead the national-revolutionary movement. But you can look through these theses from beginning to end, and you will not find those who exercise hegemony. What is the proletariat in China, what is the proletariat in India, to what extent are they organised, what is their level, what lessons can be drawn form the class struggles of the last years? These matters are mentioned casually in connection with other questions. Although everything which concerns the position of the proletariat is of the utmost interest, least of all is said precisely about this point. The labour movement in colonial and semi-colonial countries deserves our full attention. What took place in Europe and America in the course of the last 150 years (since the industrial revolution in Great Britain), we witness to-day in the colonial countries, but only horizontally. The relatively compact masses of the proletariat in China and India which knows what factory life is, the proletariat of Indonesia, Cuba, Central America, etc., which has gone through the school of capitalist agriculture on the cotton, rubber, sugar, coffee and banana plantations of the Spaniards, the Pariahs among Pariahs the black proletariat in the mining industry and on the plantations of South, West and East Africa, hundreds of thousands of expropriated natives of Africa and the Antilles, are caught in the cogs of the gigantic imperialist machine. We have before us the proletariat of all colours, all races and all degrees of development from the slave labour of the Negroes and Malays to the “free” labour of the workers of Shanghai and Bombay. We have before us as on a screen the whole past and present of the working class. This diversity in the composition, quantity and quality of the proletariat is placing before us a series of very difficult problems, both organisational and political. In some colonial countries there are already experienced fighting Communist Parties (China), fighting revolutionary trade unions (China, Cuba). In other countries the Communist Party, although it has not the experience of the Chinese Party and trade unions, has already a glorious past (Indonesia). In others again Communist Parties and trade unions are only in the making and are growing in the process of the industrial struggles of the proletariat (India). There is a series of countries where no organised Communist movement exists although there are labour organisations (Philippines). Finally, there is a series of countries where the newly born coloured proletariat is not organised at all, but answers from time to time to unheard of exploitation by spontaneous rebellions and desertion from the place of employment (East and West Africa, Congo, Portuguese colonies in Africa, etc.). Our tactic must be adapted to the diversity of the colonial countries, “it must be able to lead the advanced proletarians of Shanghai and Bombay, as well as the black slaves of the rubber plantations.” That is why we must have different slogans and special programmes of action for every country. The main thing is organisation of the rising proletarian masses. How are the workers of this or that colonial country to be organised, where is the beginning to be made, on what should one concentrate one’s attention the Comintern must give an answer to all these questions. A general scheme constructed so that it should apply to China and India, cannot give us anything. The main slogan for the proletariat of colonial countries, no matter how small this proletariat be, is organise yourselves, create your own trade union organisations which must be independent of the national bourgeoisie, create fighting Communist Parties for struggle against external and internal enemies.

Home-Made and Imported Reformism.

A big lacuna in the theses is the absence of the question of home-made and imported reformism. And yet, this is a question which deserves all our attention. There are no objective conditions in the colonies for solid and lasting reformist influence on the workers. That is why the awakening of the workers in colonial and semi-colonial countries means at the same time that these workers’ turn about face towards Moscow, the Comintern, and the Red International of Labour Unions. We have seen this in China, Indonesia, Latin America, and Africa. Only in India, owing to the peculiar development of the labour movement there, nationalists and home-made refor- mists are at the head of the labour organisations. But even there the labour movement is veering to the Left. In China only the mechanics’ union in Canton is an organisation of the Gompers’ type, whereas in the rest of China neither the Right nor the Left Kuomintang has been able to establish genuine mass organisations, although they resort to all kinds of European-American reformist methods to deceive the workers. In Egypt the Government has destroyed the revolutionary trade unions and is endeavouring to establish national-reformist organisations. The same happens in Turkey where Kemalism, after destroying the trade union movement, is establishing its own law-abiding trade unions. In Indonesia, after the suppression of the insurrection, a Social-Democratic “party” appeared on the scene. It consists of Dutch officials and of a small section of the local petty-bourgeois intelligentsia. This Party is also endeavouring to establish its own trade unions. We witness the same kind of thing in some other colonial countries. National-reformism or police reformism are appearing on the scene as soon as the colonial bourgeoisie and its imperialist masters notice that workers are coming forward as an independent factor in the struggle. But local reformism is not very dangerous because objective circumstances do not favour adherence of considerable sections of the proletariat to reformism.

Then social imperialists come to the rescue. Their special task is to tame the colonial labour movement. In this respect, very characteristic is the work of the Labour Party and the General Council in India, Thomas’ trip to West Africa, the canvassing trips of the Right and “Left” (Purcell) members of the General Council to India, establishment of a reformist party in Indonesia with the help of the Dutch Social Democrats, the efforts of the Japanese social-monarchist Bundji Suzukhi to plant his reformism in China and the sudden interest of the Second and Amsterdam Internationals in the colonial countries of Latin America. The agents of imperialism are alarmed at the development of Communism in the colonial and semi-colonial countries and are endeavouring, under the protection of the imperialist and native bourgeoisie, to divert the rapidly growing labour movement of the colonies into Social-Democratic channels. All these phenomena must be pointed out in the theses because struggle against the attempts at the reformist corruption of the workers of the enslaved countries is one of the most important tasks of the Communist International. International reformism wants to impede the organisation and welding together of the workers and peasants as well as the development of the revolutionary struggle in the colonial countries. We must resist these efforts energetically.

The International Importance of the Chinese Revolution.

Although much space is given in the theses to China, the experience of the Chinese Revolution is not made the most of, especially from the international viewpoint. After the October Revolution, the Chinese Revolution is the most important event of the present century. The greatest importance of the Chinese events consists in the response they found among the Asiatic peoples. The last three years of revolutionary struggle in China produced such a wealth of experience that it will have to be studied a long time. This experience will have to be studied from the internal and especially from the external viewpoint. The experience of the Chinese Revolution must make us study very carefully the question of mutual relations between the proletariat and the national bourgeoisie in colonial countries. Have the errors committed in China been taken into account for the benefit of other countries? They have not. In the meantime we should raise the question of the independence of the labour movement from the national bourgeoisie, the development of the industrial struggle of the workers in the trend of the general struggles, the struggle for immediate improvement of the material position of the masses, the development of the agrarian revolution, the struggle against disguising the class struggle under the colours of a united national revolutionary front, this is a necessary premise of the utilisation of the national-revolutionary movement in the interests of the mass of all the workers and peasants.

The Chinese Revolution is also instructive in regard to the mutual relations of the working class and the peasantry. The Chinese Communist Party, as represented by its Central Committee, looked upon the peasant movement, for a considerable period, as an impediment to the development of the national revolution. The Central Committee picked up the theory of excesses circulated by the bourgeoisie and, instead of placing itself at the head of the peasant insurrections, impeded and sup- pressed them together with the Kuomintang. Has this negative experience an international importance? Most decidedly so. All Parties in colonial and semi-colonial countries must be told that only in a bloc with the peasantry will the working class be able to solve the bourgeois democratic tasks confronting any given country. Agreement with the national bourgeoisie under definite circumstances and on definite conditions, with simultaneous indefatigable work for the consolidation of our own ranks, is admissible, an agreement with the peasantry is obligatory. The former is temporary, episodical, the latter is continuous, and under no circumstances whatever can and must the proletariat sacrifice the interests of the peasantry as this was the case in China in favour of a united national-revolutionary front.

We must lay special stress for all colonial countries on the necessity of feverish organisational work for the consolidation of the Party and the labour and peasant organisations. This feverish constructive work must follow the line of promotion from below, from the thick of the mass movement, of new leaders and of purging all organisations from bourgeois elements, even if they be national-revolutionary elements. Establishment of their own organisations, their own proletarian leadership, this is what we must impress the colonial Parties with. In this respect the Chinese experience is very instructive. The Communist Party and trade unions of China were almost entirely in the hands of intellectuals, representatives of petty-bourgeois circles. The more critical the situation, the more unstable became the leadership. More working class elements in all the links of the Party organisation, more manual workers in the Party Executive, more peasants in the leading posts of the peasant organisations, such must be our slogans. It seems to me that it would be useful to take into account the experience of the Chinese Revolution also in this respect.

Conclusion.

Comrades, from all I have said here I will make the following conclusion: I think that the theses laid before the Congress have very much that is valuable and deserve to be adopted by the Communist International. But to enable the international Communist movement to make use of the theses adopted by us, to be able to spread them everywhere, to make them a practical guide for our work in all countries, they must not be abstract. Abstractness and a schematic form hinder a proper understanding of the theses. Thus, if we supplement the theses by a whole series of questions which I brought forward here, if we define correctly the relation of the Indian proletariat to its bourgeoisie, if we pay more attention to the description of the labour movement in the various colonial countries, to its trade union organisations and if we explain a whole series of points which, owing to their abstract character, even I found difficult to understand, these theses will become what they should be. The international Communist movement stands in need of fully elaborated instructions re our tactic in the colonial countries. This is necessary for colonial workers as well as the workers in capitalist countries, because only on the basis of the correct tactic will it be possible to establish a closer union between the workers of capitalist and colonial countries.

It is of the utmost importance to emphasise in these theses in separate paragraphs the necessity of creating and organising labour organisations independent of the national bourgeoisie. This is mentioned casually in a whole series of paragraphs, but a question of this kind must be a central question. The premise for correct leadership in the revolution of colonial countries are proletarian and peasant organisations which do not depend on the bourgeoisie, and indefatigable struggle against imperialism, feudalism and the counter-revolutionary bourgeoisie. (Applause).

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. A major contributor to the Communist press in the U.S., Inprecor is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n76-oct-30-1928-inprecor-op.pdf