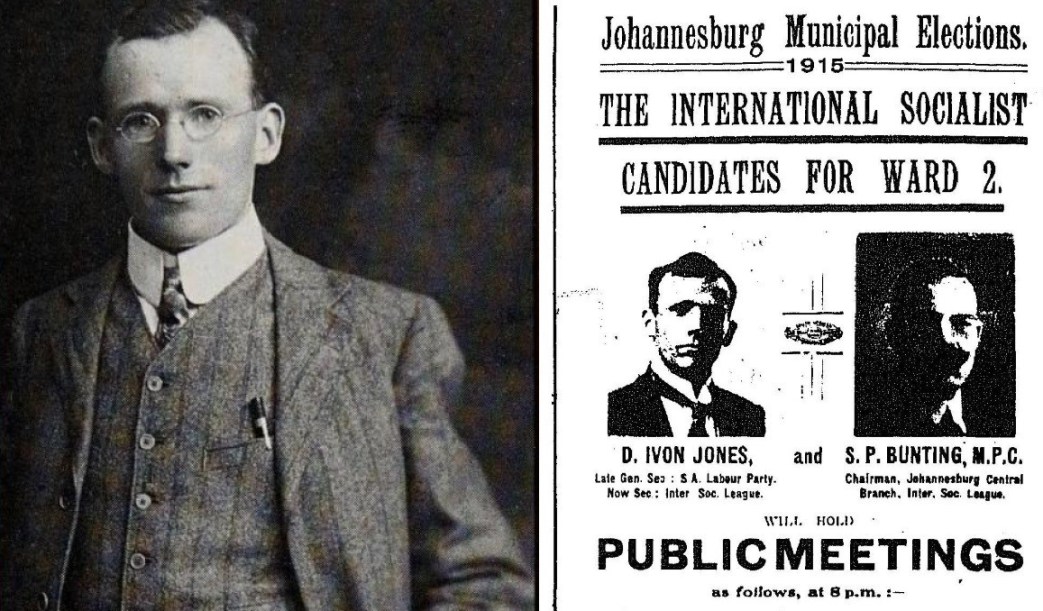

Welsh-born Marxist theorist and prolific writer, David Ivon Jones was a founder of the Communist International and central figure in the formation of South African Communism. Though he died only a year after this notable intervention, Ivon Jones as much as any white comrade steered the Comintern to face the Black and African working class. An extremely important document in the history of South African Communism, Jones’ extensive report to the Third Comintern Congress was published in abridged form for the Congress newspaper ‘Moscow,’ and later fully as a pamphlet. This is the full document.

‘Communism in South Africa’ by David Ivon Jones from Moscow. Vol. 1 No. 14. June 9, 1921.

Presented to the Executive of the Third International on behalf of the International Socialist League, South Africa.

The Third International has, of necessity, not given much attention to Africa so far, further than a passing recognition, in the heat of the European struggle that the teeming millions of the Dark Continent are also to come under its wing. Africa may not cover such a vital part of the anatomy of Imperialism as India does. But a country’s immediate contribution to the collapse of world capitalism is not its sole claim on our attention; we have to consider what positive dangers it may harbour for the movement as a whole. European capital, however, draws no mean contribution from South African cheap labour. “Kaffirs” (as gold shares are appropriately nicknamed) are the mainstay of a large section of the bourgeoisie of Paris and London. Besides which the depressing state of the vast mass of Kaffir labour from the point of view of proletarian development- illiteracy, generally low social and civil status and backward standards of life is not a matter to which the Communist International can remain indifferent.

Africa’s hundred and fifty million natives are most easily accessible through the eight millions or so which comprise the native populations of South Africa and Rhodesia. Johannesburg is the industrial university of the African native, although recruiting for the mines has been confined in latter years to parallel 22 in Portuguese territory.

South Africa, moreover, is an epitome of the class struggle throughout the world. Here Imperial Capital exploits a white skilled proletariat side by side with a large native proletariat. Nowhere else in the proportions obtaining on the world scale do white skilled and dark unskilled meet together in one social milieu as they do in South Africa. And nowhere are the problems so acute of two streams of the working class with vastly unequal standards of life jostling side by side, and the resultant race prejudices and animosities interfering and mixing with the class struggle.

SOUTH AFRICAN POPULATIONS.

The Union of South Africa, occupying the country South of the Limpopo River, comprises the old Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, the old British Colonies of Natal and Cape of Good Hope. These now form one Government with their own local Provincial Councils. The more sparsely settled areas of Rhodesia and German West Africa are not yet in the Union. The white population of the Union is divided almost equally into Dutch and English extraction, with a large Jewish population in Johannesburg. The whites number about a million and a half. The feuds existing between the two main sections of the white population are matters of history, and animosities resulting therefrom are serious political factors at the present day.

The native population of the Union numbers about six millions. The native race is mainly composed of one type, called the Bantu, meaning “folk,” divided into several tribes which have their remnants’ of means tribal territory in Zululand, Basutoland, Swaziland, etc., nominally under the protection of the Imperial Government; in practice, however, the native peoples are governed by the Union’s Native Affairs Department.

Between the black and white peoples there are shades. There is what is known as the coloured people. In South Africa coloured “half-caste.” The coloured population, inevitable accompaniment of a black and white society, numbers hundreds of thousands, mainly in the Cape Province, with large numbers in Kimberley, Johannesburg and Durban, and other industrial centres. They are a social link with the natives, though not socially intermingled. They are a section apart, aspiring to the social standards of the whites and invading the skilled trades. In the Cape Province coloured people enjoy the civil and political rights of the whites with a far larger measure of social equality than in the Transvaal.

In Natal, is centred a considerable Indian population, originally indentured to the Sugar Estates. A large proportion of these people are South African born. They socially intermix with the coloured people. Further immigration of Indians is prohibited in the Union.

INDUSTRIES.

In a country of a million square miles, agriculture is of necessity a staple industry, though the old Boer farmers’ methods are obsolete, and there are vast tracts of land held up idle by the landed syndicates in combination with the mining houses.

The Gold Industry of the Transvaal, with its Witwatersrand gold reef sixty miles long, is a world-renowned phenomenon. The Reef, with the town of Johannesburg as its centre, provides the economic stimulus for the whole country. The diamond mining industry of Kimberley and Pretoria, the coalfields of the Transvaal and Natal, the Sugar Estates of Natal, sum up such industries as affect the world market. The Railways are owned by the State.

POLITICAL AND SOCIAL CURRENTS.

In such a milieu one may guess that the social relations are rather complex. After the overthrow of the old Boer Republics, the Boer political leaders, Botha and Smuts, proceeded to make friends with the mammon of unrighteousness, and fitted themselves to govern by acquiring interests in land and gold mining. By 1907 they were deemed sufficiently safe to be entrusted with self-government. There was a distinct subsidence of the animosities aroused by the war. After the Union of the Provinces in 1910 the Dutch Party was again entrusted with the Government. Hertzog, the present leader of the Republican Party, was at that time the left wing representative of the Dutch in the Cabinet as Minister of Justice, and, it may be observed in passing, the first to conceive the brilliant idea of arming the mounted police with pick handles to beat down the tramway strikers of Johannesburg. After his expulsion from the Cabinet in 1912, the Dutch Party split up into the present South African Party led by Smuts and the Nationalist Party led by Hertzog, who, since the great war, gives half-hearted homage to the republican idea, and Tielman Roos, the more thorough-going republican leader. Since 1912 those “heralds of ill will,” Dutch Nationalism and British Chauvinism, further fostered and embittered by the world war, have sounded the slogans of Capitalist Imperialism versus petty bourgeois federalism. During the war the Dutch Nationalists broke out into open rebellion. It was, however, speedily suppressed. Latterly the Party has gained popularity at the polls with its republican and populist programme, appealing as it does to the increasing mass of disinherited Dutch Afrikanders. This has caused the consolidation of the British Unionist Party with the Dutch South African Party. The February elections showed that the Nationalist farmer recoiled before the consequences of the Republican propaganda, and the Government Party obtained a safe parliamentary majority for the Imperial connection.

DUTCH NATIONALISM AND THE NATIVE.

The great festival of the Dutch Afrikander people and of the Nationalists in particular is Dingaan’s Day. This day is made the occasion of political appeals on present issues, as well as a commemoration of December 16th, 1838, when the Dutch Voortrekkers crushed the power of the Zulus in a bloody battle fought on the Blood River, Weenen. On this festival the dual oppression bearing on the small Dutch farmer are inveighed against; justifiable hate of British imperialism and of the British Chauvinist on the one hand, and hatred of the progeny of Dingaan on the other, his own hewers of wood and drawers of water. “Presbyter is only Priest writ large.” More glaringly than in most Nationalist movements, the freedom demanded from British rule is almost avowedly freedom to more fully exploit the native. As a concession to Nationalist sentiment, Dingaan’s Day has now been officially declared a legal holiday throughout the Union. On these days, as on others, the rifle and the sjambok are invoked as the appropriate remedy for native grievances. In his personal relations the Dutch farmer adopts a quite friendly and patriarchal attitude towards his native labourers, provided of course they keep their proper stations. To the old Boer, the native is a simple beast of burden. His religion is that of the Old Testament. It involves no contradictions, for his economic environment is primitive, though rapidly changing now with the advance in agricultural methods. General De Wet’s excuse for going into rebellion in 1914, was that he had been fined five shillings for flogging a native servant-an unpardonable restriction on personal liberty! The Nationalist movement has a literary reflex. What there is of Afrikander literature is, of course, inspired by Nationalism. But the mania for isolation reaches absurd lengths. For example, Holland Dutch is one of the official languages of the Union. But the spoken language is a crude patois called Afrikaans. Previously the Dutch Afrikanders were content to let Afrikaans remain the spoken language, and used Holland Dutch as a vehicle of religion and literature. But now, the Nationalist movement resents Holland’s intellectual patronage as much as Britain’s Imperial dominance. Though there are no fixed standards of grammar or style or spelling in Afrikaans, it is now being tortured into requisition as a literary medium, and the upholders of “Hollandse” are stigmatised as the creatures of Smuts. The treasures, historical and literary, of the mother Dutch are thus thrown overboard; but the young Afrikander intellectuals cannot possibly endure such a self-imposed sentence of solitary confinement for very long.

Our remarks on this movement, as the movement of a class, must not be construed to apply to our Dutch friends as a race. They partake of the virtues of all good people. In the feud with the British it is they who have always held out the hand of conciliation, often spurned with insult by the British Jingoes.

BRITISH CHAUVINISM.

Among the British section of the population there is a corresponding animosity towards the Dutch Afrikanders. The recent elections show that the Republican scare took away many votes which had previously been given to the Labour Party, although that Party blows the Imperial trumpet loudly enough. But this brand is too notorious to need any description here.

FRANCHISE ANOMALIES.

Only whites are qualified to vote in the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. In Natal the coloured people are qualified to vote, and even natives, but on terms so strict that only three or four individuals are able to avail themselves of it. In the Cape Province, besides manhood suffrage for whites and coloured, natives are also qualified to vote on certain slight education tests, and the coloured and native vote is a serious electoral factor to be reckoned with. These disparities of franchise rights obtaining for the various provinces are inherited from the pre-existing provincial governments, and are the cause of the most amusing antics of electioneering parties operating simultaneously in the different provinces. The liberalism of the Cape is the legacy of the old Free Trade Governors of the Victorian period. In those days, Manchester looked upon native populations more as buyers than as cheap labourers- people whose standards of culture and, above all, wants should be improved.

In the Transvaal, thanks to the slave-holding traditions of the old Boer voortrekkers, Imperialist Capital with capital to invest rather than goods to sell, found cheap labour in a civil milieu to its liking for the exploitation of the gold reefs.

These political cross currents produced some curious effects during The British workers cried down our anti-militarist declarations, while the Dutch approved. But coming to our native workers policy, it was then the turn of the Dutch to decry, while the British with their trade union traditions were prepared at least to listen. We were being repeatedly consigned to prison by the Johannesburg magistracy; and the judges, drawn largely from the older population, has repeatedly quashed the sentences.

The Indian traders, who are fast gaining control of trade in Natal and other parts of the Union, are the cause of much heart-burning among the white traders, and anti-Asiatic movements, into which the workers are often dragged, are frequent.

Among the Trades Unions of the Transvaal, the wage-cutting effect of the coloured labour that swarms to the industrial centres is a burning question, aggravated as it is by the short-sighted policy of the Unions in excluding the coloured worker from membership. This time it is the turn of the employing class to sneer at Labour’s inconsistency. the war.

WHITE LABOUR MOVEMENT.

The white Trade Union movement in South Africa dates from the end of the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902, although such trades as the Typos., Engineers, and Building Workers were organised in South Africa previous to that. W.H. Andrews, prominent among those who did the spade work of the Transvaal Labour Movement, is still to-day active, blazing the trail of the Communist Movement. The growth of the movement was marked by the usual steps of the formation of unions in the different trades, the Trades Council of Johannesburg, from which sprang later the Federation of Trades and the Labour Party. After the Boer War, the gold magnates profited by their victory to introduce Chinese labour into the gold mines of the Rand. This created a White Labour Policy League, of which Creswell, then a victimised mine manager, was the head. This movement also mixed itself with the labour movement and brought Creswell into the Labour Party, of which the capitalist press soon appointed him popular leader in opposition to the class leadership of Andrews. In 1910, when the four provinces formed a Union Government, the South African Labour Party was inaugurated out of the various Provincial parties. This party had a Socialist objective in its platform, as also a demand for the abolition of the indentured system of native labour and the prohibition of the importation of native labour from territories outside the Union. The Party started in 1910 with four members in Parliament; it gained another four in by-elections up to 1915. The Party very soon became the accepted political expression of the white workers, its class-conscious elements, rather than the White Labour Leaguers of Creswell, being, dominant. At that time class-conscious meant white class- conscious, and the native as a fellow-worker and a comrade in industry never entered into any Labour calculations; neither did the idea of Labour enter the native mind, so well defined were, and still are, the respective industrial functions of black and white. Indeed, the wholly utopian proposal of segregation of black from white in strictly delimited areas, in accordance with the scheme of the White Labour League, and the withdrawal of the native from white industry, was the only Labour proposal for the natives up to the time of the war.

In 1913 a general strike of white workers broke out on the Rand, causing a complete stoppage of the gold mines for the first time in their history. This strike was a bloody affair. Troops were called out, and shootings by the regular troops resulted in 22 persons being killed and several hundred wounded. At that time the Chamber of Mines, which employs about 20,000 whites, had not learned the value of class collaboration—a wrinkle which Syndicalist Crawford* taught them later. In 1914 another general strike broke out, this time forced upon the white workers by the Government, which spread to all parts of the Union. The massacres of 1913 had brought the workers an unexpected victory; but in 1914 the Government had prepared in a military manner. Martial Law was proclaimed, and 60,000 burghers from the veld were armed and put in possession of Johannesburg, having first been told that the English were making war again. The workers were driven back to work and leaders imprisoned by the dozen. Nine trade union leaders, and others who were by no means leaders, were deported by force to England.

The indignation against deportation found a vent in the ensuing Provincial Council elections, when the Labour Party obtained a majority of seats in the Transvaal. This resulted in a large influx of middle class elements into the Party. The outbreak of war found the Party divided on the question of militarism, but the Executive was anti-war, though few in a truly revolutionary sense. At a special conference of the Party held in 1915 the Executive were defeated by an overwhelming majority on the war issue, and were thereby forced to resign. The Creswell faction carried things with a high hand, and forced every candidate to give a written undertaking to “see the war through.” The anti-war section broke away, and with the co-operation of what were called the S.L.P. men (comrades like John Campbell and Rabb, who propagated the principles of Marxism as formulated by De Leon) formed the International Socialist League, which is to-day the South African section of the Communist International. The League started its career backed by the majority of the Labour Party Executive, including the Chairman (Andrews) and the Secretary (Ivon Jones), who took similar positions in the new organisations. It, however, soon shed its Reform Pacifists on the adoption of a revolutionary programme and the extension of the class struggle to include the native workers.

THE ERA OF COLLABORATION.

The Labour Party, thus rid of its anti-war executive, fought the elections of 1915 on the cry of “See it through,” and for its pains got its Parliamentary representation reduced from eight to four. Up to the time of the split the Labour Party was composed of open political branches, and the Trades Unions affiliated or deaffiiated to the General Council, according to the fluctuating votes of their respective memberships. Up to the war the Party was largely composed of elements from the trades unions, the Engineers, Carpenters, Miners, Boilermakers, and Printers being affiliated. On the war issue the trades unions followed Creswell’s lead, but they seem to have very soon got ashamed of their handiwork, for to-day there are no trades unions affiliated to the Party, which has deteriorated as a machine into a collection of electioneering committees trading on the name of Labour. This is partly due to the increasing number of Communist supporters among the active elements of Trades Unionism; and partly to the influx of Dutch workers into the towns for which the unions must “cater.” To these workers the Labour Party is anathema, for it has by its beating of the Jingo drum violated their legitimate national sentiments.

Nevertheless, in the general elections of the early part of 1920, the Labour Party, by a judicious handling of the two issues of the Cost of Living and the Imperial connection, pulled off twenty-one seats. But at the general elections of the early part of 1921, when Smuts forced the issue of the Imperial connection against the Republican propaganda, the Labour Party, led by Creswell, though it jettisoned the “Red Flag,” all its economic demands, as well as the Jonah of Socialism, and frantically protested on every platform that it was faithful to the Empire, only obtained nine seats, Creswell himself being beaten. This looks like its final decline. The factors are too complex in South Africa for a powerful Social Democratic Party.

During the war the White Trades Unions gained enormously in membership, and lost equally in fighting spirit. Crawford, at one time anarcho-syndicalist, is now the apostle of class collaboration, and as Secretary of the S.A. Industrial Federation, is the willing agent of the Chamber of Mines.

LABOUR ARISTOCRACY.

The failure of the anti-war Executive of the Labour Party to keep the workers to the class struggle was due to the fact that, in the white worker, consciousness of class is, so far, fitful and easily lost. He is used to lord it over the unskilled native as his social inferior. The white miner’s duty is almost wholly that of supervision. With the fitters and carpenters the native labourer does no more than the fitter’s or carpenter’s labourer in European countries. But he is black, a being of another order, and moreover only has half a shirt on his back, more for ornament than for use, and sleeps in a tin shack. As workers whose functions are wholly different in the industrial world, there is hardly any com- petition involved; indeed, the white miner is as much interested as the Chamber of Mines in a plentiful supply of native labour, without which he cannot start work. They are therefore annoyed at any strikes of natives, and are prone to assist the masters in their repressive methods, although in the case of white strikes they are not behindhand in appealing to the natives not to go down the shafts; and the natives, as a rule, are unwilling to go without the white miners. For between white and native worker there is, as a rule, the best of good humour at the place of work. The native addresses the white worker as “boss,” it is true, but this term has now become almost a convention like “sir,” and there is no doubt that the native is animated by a large measure of respect for the white worker as his industrial educator, a respect which will find more generous play on both sides in a better economic order. One of the nightmares of the white miner is that he may lose his monopoly to the legal right of holding a blasting certificate. Under such conditions what wonder if consciousness of class among the mass of white workers is somewhat narrow and professional.

During the war, the capitalists, urged by the necessity of keeping up gold production, discovered that it paid them to regard the white workers as an unofficial garrison over the far larger mass of black labour, and that it was not bad business to keep the two sections politically apart by paying liberally the white out of the miserably underpaid labour of the black. The white workers were far more intractable to Communist ideas at the end of the war than in the second or third year when the colonial campaigns were in progress. The premium on the mint price of gold enabled the Chamber of Mines to keep up this policy of economic bribery till the end of last year. Now it seems as if it had come to an end. The bribe fund has petered out. The premium on the mint price of gold is being reduced, and under the threat of closing down the non-paying mines the white miners are compelled to accept lower pay. During the last few months there have been unofficial strikes against the will of the Union Executives and of Crawford, the Federation Secretary. The mines have retaliated by withdrawing the “stop-order” system. This system, introduced in 1916, was an ingenious bait to trade union officialdom. Every miner had his trade union contribution deducted at the mine office from his wages, and the mine offices handed it over to the union in a monthly cheque, thus making the Union an adjunct of the Chamber of Mines. “Now this “privilege has been ” withdrawn as a measure to weaken the none-too-pliant membership. The garrison is too costly. The mining industry can only save its profits by following the historic process, namely, to raise the black standard and depress the white, making towards a homogeneous working class.

RURAL MOVEMENTS.

Here is no white labour movement of any kind in the country districts of South Africa, excepting, of course, the attempts at organization in the townships wherever cheap white, coloured and native labour are engaged in local industries. The natives do nearly all the farm labouring. The sons of the Boer farmers, no matter how impecunious they may be, are generally too race-proud to labour on the land. In any case the cheap native labour tends to drive all but white proprietors to the towns. The laws of inheritance are measures of disinheritance. The farms are divided up amongst the children, calling for more intensive culture, to which the Dutch farmers have not been trained, the old system of pasturage enabled the farmer to sit on his stoep and smoke his pipe. Thus the farms fall to those who bring progressive methods of agriculture to bear on the land. There is a considerable class of landless Dutch Afrikanders. They eke out a living on the “bywoning” system, by which they are allowed to occupy a hut and pasture and cultivate a small corner of a farm in return for services to the farmer when called upon: a kind of servitude. But this system is falling into disfavour with the rich farmers. They prefer the “squatting system,” a species of sub-letting to natives on half shares. There is, therefore, a constant stream of landless Dutch to the towns. Large numbers are employed in gangs, called poor white gangs, on pay so miserable that they are in a constant state of semi-starvation. These cast-offs from the rural districts, spurned socially and economically by the very class of nationalist farmer whom they follow politically, help to make up the slums of Johannesburg, Vrededorp, the Johannesburg slum district, is a social cesspool where the Dutch, English, Indian, Coloured man, Kaffir and Hottentot all at last find equality in wretchedness, equally of no account to the capitalist class. It would be hard to find a parallel for Vrededorp in any town in Europe. The rigorous anti-liquor laws, which make it a penal offence to give alcohol to natives in the Transvaal, find their victims in this class. Three-fourths of the white inmates of South African prisons are convicted of selling drink to natives; that last tempting resort of the destitute and miserable.

As a result of the migration to the towns, the urban workers are becoming increasingly Dutch. Before the war the Executive of the Mine Workers’ Union was wholly of British descent. Now more than half are Dutch Afrikanders. The tramway systems and semi-skilled services are now largely run by Dutch workers, who soon develop into good trades unionists and loyal agitators for their class, always, of course, within the limits of their colour. At a local strike on the Simmer Deep mine last year, when both British and Dutch miners stopped work as a protest against the dismissal of a German member of the Union, both sections tacitly dropped their respective nationalisms for the time being; and it was good to see the young Dutch workers, who a week before and perhaps the week after, sported their nationalist green and yellow, on this occasion proudly wearing their bits of Red as the only suitable emblem for such an occasion as a strike. The industrial system is also weaning gradually the Dutch workers from the most violent forms of colour prejudice. The traffic of Dutch workers to and fro is linking up town and country as never before; and the expropriated Dutch of the country districts will soon share in the inevitable change of outlook.

THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIVE.

Speaking generally, the South African natives are a race of labourers. The bulk of the race is now found interspersed in white areas. Certain territories are still reserved for their tribal homes, such as Zululand, Basutoland, Swaziland and Bechuanaland. In these areas a sort of primitive communism exists as far as the land is concerned. What little government of local matters is required in a society where there is very little property is exercised by the chiefs, petty chiefs, and Headmen, always, of course, under the supervision of the police patrol. The perpetual sunshine renders maize the only prime necessity. Zululand, for example, is a land of free and rolling “savannah” with no property boundaries; dotted with the round straw huts of the Zulus, which are without windows or outlet for smoke, and with only a low hole in the structure to creep in and out. Round the huts are the small patches of maize chiefly dug by hand, or of idombis, a kind of Zulu potato. The natives in their tribal state live very closely to the soil, they and their habitations seem part of it, elemental in their simplicity of life. In Basutoland they are more affluent, owning horses and cattle; and of late an increase in cattle is to be observed in Zululand also, enabling their owners to plough at home instead of going to labour for the whites. In the Transkei, Cape Colony, a system of native small proprietorship was tried, known as the Glen-Grey settlements. But this is an exception to the general scheme of things. A recent clamour from white settlers that Zululand should be opened up for settlement for white farmers was answered by Minister Malan that this was out of the question, as it would increase the cost of native labour for the whole country. This, then, is the function of the native territories, to serve as cheap breeding grounds for black labour- the repositories of the reserve army of native labour—sucking it in or letting it out according to the demands of industry. By means of these territories Capital is relieved of the obligation of paying wages to cover the cost to the labourer of reproducing his kind.

Between the territories and the industrial centres there is a constant traffic to and fro of natives. What draws the native away from his home? The marriage customs are a cause. Wives are worth so many cows, and money must be got to buy them. But the chief impulse is the hut tax specially levied for the purpose; besides which large numbers are allured to the towns by social instinct and the excitement of town life among so many of their own folk there, so that the first excursion from home in many cases becomes a permanent absence. For the native there is the prospect of learning to read and write; he has a keen desire for education. There is the native church in the towns, either as an adjunct of the white religious bodies or his own Ethiopian church, an institution frowned upon by the white Christians for its lack of respectable guidance in the interpretation of the gospels! There is the allurement of machinery. The native is captivated by a piece of machinery, and will seek out its inmost pulsations and tend it as a god. In the towns also there is freedom from the social interference of the chiefs, even if obtained at the cost of subservience to white society. For native women there is emancipation from the tribal marriage customs; tens of thousands of native women are detribalized by contracting free liaisons in the towns not sanctioned by tribal custom. The chiefs are benignant enough old institutions. But they bewail their disappearing authority, although they are useful to the capitalist for the recruiting of labour. In a prosecution in which we were involved for a Bolshevik leaflet addressed to natives as well as whites, the Crown Prosecutor continually referred to those town natives who no longer own allegiance to the chief as “the hooligan class of native,” that is, they are no longer under official control. They have taken the step from tribesman to proletarian.

Outcast and outlawed the native may be, but no “hooligan.” In the Transvaal and the Free State Province the native has no vote, no civil and political rights. A breach of labour contract is a penal offence. The natives on the mines work on a system of indenture, generally of one year’s duration. They do not live in private dwellings, but are herded into “compounds” adjacent to the mines. Indeed, native housing in the towns is not fit for cattle. Most of the hundreds of thousands of natives who work in the towns are housed in backyards, tin shacks, stable lofts, the best way they can. Their level of existence is inconceivably low. Every native male must carry a passport: one to leave his tribe, another to seek work, a monthly pass while working, another pass when he wants to be out after nine o’clock curfew. A policeman may at all times stop a native and demand his pass. Hence most natives have been to jail at one time or another. This is a mere trifle to him with all the regulations that hem round his daily life. He is paid two or three shillings a day, with or without his ration of mealie meal, as the case may be. A rise of a shilling a day would create a panic on the gold market.

Yet in spite of it all, the Bantu is a happy proletarian. He has lovable qualities. “His joy of life and fortitude under suffering” to quote Lafargue’s words on the negro; his communal spirit, his physical vitality, his keen desire to know, despite his intellectual backwardness, make him an object of lurking affection to the whites who come in contact with him.

Moreover, he is no fool. He has a certain naïve wisdom which goes to the root of things. It was the questionings of the Zulus that led the celebrated Bishop Colenso to change his religious views. Arrested development of the native mind has been a theory very much resorted to by negrophobes. To the exploiters, the less a man has the more must be taken from him. Some bourgeois negrophiles, like Loram the Natal educationalist, have even gone to the pains of disproving this meaningless theory. To us it suffices that the native workers are the producers and are robbed of the products of their labour. The truth is that a radical difference in psychology exists. The native bends to capital, but capital also bends to his primeval instincts. See a gang of natives working on the roads or railways! On every possible pretext they will work in unison, raising and lowering the pick, with rhythmic flourishes thrown in, to the tune of their Zulu chants. Ever and anon the tune or the time changes, in an endless variety from the ancestral repertoire, in perfect harmony and rhythm-impromptu choruses of the wild, charming, even the dullest. No gaffer can speed up such a gang. And when the same gang tries to sing a simple Christian hymn it makes a most discordant mess of it. Such is arrested development!

THE NATIVE LABOUR MOVEMENT.

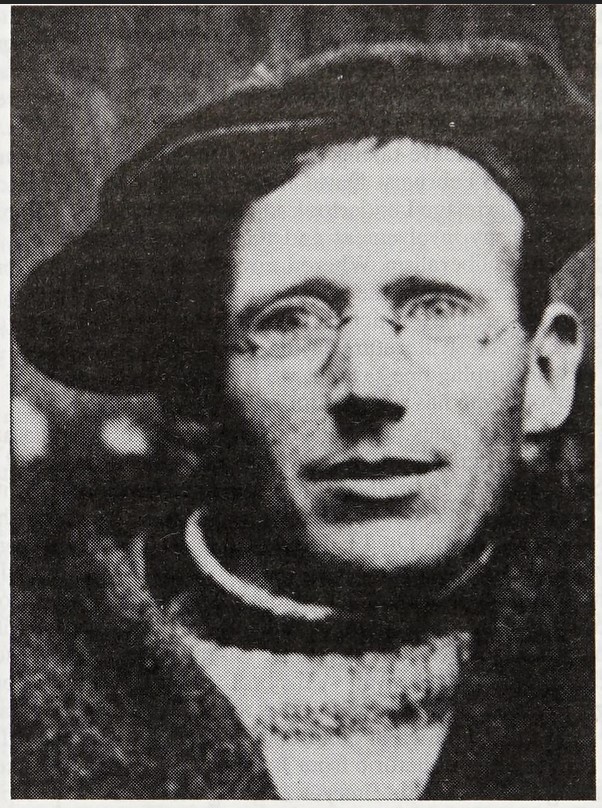

A formal statement of the various categories of native labour and the true Communist policy towards the native workers has been prepared by Comrade S.P. Bunting and accepted by the International Socialist League.

Before the war no trade union movement existed among the native workers, and such a thing as a strike was unknown. The first move in the direction of organised revolt was a strike of native workers on the dumping machinery of the Van Ryn Gold Mine in December, 1915. It was regarded as a novel affair by the white workers of the mine: but it appears that certain white men who engaged to keep the plant going were sneered at as blacklegs by their white fellow-workers. Prior to that, in the 1913 revolt of the white workers, appeals had been made to the native workers of the Kleinfontein mine to stop working, and it seems to have dawned then on the white workers’ intelligence, or some of their most militant leaders like George Mason, that the native was really a kind of a workmate. In 1917, Comrade Bunting and other members of the I.S.L. made an attempt to form a native workers’ union. A number of the more industrialized natives of Johannesburg were enrolled into the Union, which was named the “Industrial Workers of Africa” (an echo of the “Industrial Workers of the World”). It held meetings regularly, and the message of working class emancipation was eagerly imbibed for the first time by an ardent little band of native workers who carried the message far and wide to their more backward brethren. A manifesto to the workers of Africa was issued in collaboration with the I.S.L. written in the Zulu and. Basuto languages, calling upon the natives to unite against their capitalist oppressors. This leaflet reached a still wider mass of native workers, and was introduced and read to the illiterate labourers in the mine compounds. For the native of Africa, and the white too, for that matter, the question is not yet irrevocably put of “bloody struggle or death.” It is the era of awakening to the consciousness of class. The emphasis of the League on the new power of industrial solidarity, which their very oppressors had put in their hands, had as its aim to draw away the native’s hopes from the old tribal exploits with the spear and the assegai as a means of deliverance. The power of the machine dawned upon him. In 1918 the propaganda of the I.W.A., and the pressure of the rising cost of living, produced a formidable strike movement among the native municipal workers, and a general movement for the tearing up of passports. Hundreds of natives who had burned their passes were jailed every day, and the prisons became full to bursting. Gatherings of native men and women were clubbed down by the mounted police. The International Socialist League was charged with inciting to native revolt. Comrades Bunting, Tinker and Hanscombe were arrested at the instance of the Botha Government; but the chief native witness for the Crown broke down. He admitted that the evidence of incitement to riot had been invented for him by the Native Affairs Department, and the case collapsed. The moving spirits of the I.W.A. were driven out of Johannesburg by the police, some to find their way to Capetown, where a more permanent movement of native organization has since been formed. It has also spread to Bloemfontein, where Msimang, a young native lawyer, is active in native organization. In the Cape Province the natives are more advanced politically, and more permanently settled in the European areas. But the greater civil equality does not bring greater freedom to combine. Masabalala, the leader of the Port Elizabeth native workers, was imprisoned last August for his trade union activity. Trade unionism among the native workers makes the hair of the South African bourgeois stand on end. But the result of Masabalala’s imprisonment was that his comrades rose en masse and tried to storm the prison. A massacre by the armed police ensued: and the “white agitators of the Rand” blamed as usual.

But the most portentous event so far in the awakening of the native workers was the great strike of native mine workers on the Rand in March, 1920. These mine natives are mostly raw recruits from the tribal territories, from Zululand, Basutoland, faraway Blantyre and Portuguese Africa, all are here. For the time being all the old tribal feuds were forgotten, and Zulu and Shangaan came out on strike together irrespective of tribal distinction, to the number the number of 80,000. Without leaders, without organization, hemmed in their compounds by the armed police, the flame of revolt died down, not without one or two bloody incidents in which the armed thugs of the law distinguished themselves for their savagery. The I.S.L. at the time was engaged in the general elections, printing literature on the Soviets and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat for its five candidates. The white workers were undecided as to their attitude towards the native strikers. The I.S.L. came out with an appeal in The International and in thousands of leaflets entitled “Don’t Scab,” calling upon the white workers to play the game towards the native strikers. These distributed in the mine shafts by Communist sympathisers among the miners. One or two were made the object of a prosecution by the police, but released later owing to the difficulty felt, no doubt, of getting at the I.S.L. for propaganda, were in the heat of an election. The Capitalist Press, thinking to damage our election prospects, gave still further publicity to our appeal by reproducing it in full as a proof of our criminality! The Mineworkers’ Union Executive called upon its members to side with the masters and endeavour to run the mines, and publicly condemned our propaganda. But such is the division of labour in South Africa that whereas either black labour or white labour can stop industry, neither can properly start the wheels going again without the other.

NATIVE POLITICAL LEADERS.

There exists a body known as The Native Congress, with sections functioning in the various Provinces and for the whole Union. This is a loosely organized body composed of the chiefs, native lawyers, native clergymen, and others who eke out a living as agents among their compatriots. This body is patronized and lectured by the Government. It has weekly newspapers in the various provinces: Abantu Batho in Johannesburg, Ilangu Lasa Natal in Natal, etc. These are subsidized by Government advertisements, which are often withdrawn when the Congress drops the role of respectable bourgeois which it normally tries to assume. It is satisfied with agitation for civil equality and political rights to which its members as a small coterie of educated natives feel they have a special claim. But to obtain these the mass cannot be moved without their moving in a revolutionary manner. Hence the Government is dubious about the Congress, and the Congress draws back timidly from the mass movements of its own people. The native workers of the I.W.A. quickly grasped the difference between their trade union and the Congress, and waged a merciless war of invective at the joint meetings of their Union with the Congress against the black-coated respectables of the Congress. But the growing class organizations of the natives will soon dominate or displace the “Congress.” The national and class interests of the natives cannot be distinguished the one from the other. Here is a revolutionary nationalist movement in the fullest meaning of Lenin’s term.

NATIVE EDUCATION, ETC.

Apart from work done by Christian missions, the natives are thrown largely on their own resources for their education. Reading and writing are not necessary to their industrial function, so they have to acquire these at their own night schools, those who have the ambition. Here is a grand field for Communist activity given the necessary personnel and the money. In the Cape and Natal there are voices heard in favour of education for the natives. Farseeing bourgeois like Sir William Beaumont in Natal are advocates of votes for the native, with education, in order, as he says, that the native may be taught to vote as a good citizen, that is, as a good bourgeois. The mining industry has been wobbling in its attitude towards the educational and civil advancement of the natives, being hindered by political organizations, and the Franckenstein of race prejudice which it has itself conjured up, from reducing working costs by opening the higher industrial employments to natives and coloured men. In the last few years The Star, the Chamber of Mines daily, has incessantly declared in favour of the civil advancement of the natives, vigorously attacking the white unions for their denial of equality of opportunity to the native worker. These appeals, made in the interest of lower working costs, are nevertheless unanswerable in logic from the Labour point of view. The native does not care what the motive may be. He sees in his economic exploiters the champions of his civil rights. Now that the capitalist parties are safely seated in the Government saddle we may look forward to steps being taken to realize the programme. After the native strikes of 1920 the Chamber of Mines issued a newspaper for distribution gratis, printed in the native languages. Its leading articles were chiefly devoted to discrediting the Socialists and white agitators generally. The I.S.L. had under consideration the issuing of a Communist sheet in counterblast, but found itself unable to do this in addition to The International. This attempt to debauch the mind of the native workers while it is in the process of awakening is one which the Communist movement is too weak to frustrate; and we can only call the attention of the Third International to the fact.

THE I.S.L. AND ITS TASK.

The International Socialist League, soon after it parted company with the Labour Party, declared for the solidarity of Labour irrespective of race, colour or creed. Imbued with the ideas of De Leon, as popularized in the splendid series of Marxian pamphlets issued by the S.L.P. of America and Great Britain, the League proclaimed the principal of Industrial Unionism, placing in the Parliamentary fight the fight to end parliaments, and to replace them by the class state of the workers functioning through their industrial unions. Therefore craft unions were declared odious as dividing the workers instead of uniting them on the larger basis of industry. And as part of this craft disunity the exclusion of the native workers from part or lot in the Labour Movement was denounced as a crime. To us, the rather mechanical formula of De Leon’s Industrial Unionism (which was deemed capable of performing a bloodless revolution by “a lock-out of the capitalist class”) was made a living thing by its application to the native workers. Later on the word became flesh in the Soviets, and we no longer worry overmuch about the craft or professional form which the older unions have taken.

The League having thus been captured by the De Leonites, the reform pacifists gave us the cold shoulder, and several slunk back into the Labour Party. The League also formed branches which have had fluctuating success in the Reef towns of Krugersdorp, Benoni, Springs and Germiston, also at Durban and Kimberley. Durban has also had for years a small group calling itself the Social Democratic Party, followers of Hyndman in war and peace. This body refused to link up with the I.S.L. on the excuse that we were only the Labour Party under another name. It was allowed to hold its meetings during the war by an arrangement with the police that it would leave the war out of its propaganda. At this time the I.S.L. was being mobbed by the organized hooligans of the police and prosecuted for its class war propaganda. This S.D.P. outfit still follows Hyndman in sneering at the Third International and the Russian Revolution, and may justly be put down as of no account. The Social Democratic Federation of Capetown was also unwilling to link up for other reasons. It was composed of pro-warites and anti-warites, and the Jingoes and Pacifists remained in peace together. The I.S.L. was reformist because it fought elections, and the “men from the north,” as they called us, were accused of trying to sow disunity in the Federation by its neophyte enthusiasm for Karl Marx as the only authority! Comrade Harrison, one of the members of the S.D.F., carried on a valiant open-air propaganda on anti-militarism and what he calls “philosophical anarchy,” for which he was repeatedly prosecuted. Latterly a body of young class war enthusiasts broke away from the S.D.F. and formed the Industrial Socialist League. Anti- political, they thought to emphasize the fact by the word “Industrial.” It has now proclaimed itself the Communist Party of Africa. The I.S.L. itself also suffered a breakaway of anti-political anarchists for its persistency in fighting elections. This group also formed itself into a “Communist Party” in unison with the Capetown group. The I.S.L. has made attempts since the proclamation of the Moscow theses to unite these groups into the Third International. The reply of the Johannesburg group objected to the twenty-one conditions and to the “dictatorship of Moscow” (meaning the dictatorship of the Marxian principles). Comrade E.J. Brown, a member of the I.S.L. recently expelled from the Belgian Congo for trade union agitation there, has been more successful in Capetown in the matter of unifying the sound revolutionary elements, and forming a group anxious to fight under the banner of the Third International. The I.S.L. waits on these elements to fall into line before definitely transferring itself into the South African Communist Party of the Third International.

The number of Leagues and Parties all claiming to be revolutionary must not be taken as indicating a large revolutionary following. The I.S.L.’s election results have been very meagre indeed. The best poll was that of Comrade Andrews in Benoni in 1917 with 335 votes against 1,200 odd for the successful candidate. Since then the election results in Benoni have dwindled considerably. The mass of voteless native workers makes it impossible for us to win elections in South Africa. The necessity for propaganda, the need to keep the two streams of the proletariat theoretically one, the need to appeal on the political plane on class issues affecting the native, and above all the advisability of opening as far as possible the arena of civil right for the native struggle makes it imperative nevertheless that we fight elections. The League is by far the largest of the groups that I have mentioned, undoubtedly larger than all the rest combined, and the only one of any political significance. Any worker who puts up a fight for class solidarity in the Transvaal Unions is thereby deemed a sup- porter of the I.S.L. It has a large circle of passive sympathisers, as evidenced by the number that follow its banner in the May Day procession, in which the trade unions. co-operate. Nevertheless, the League’s membership has never exceeded four hundred at any time. And latterly the number of militants who have emigrated to Europe has weakened our organization. It is denied the support and inspiration of the great mass of the propertyless proletariat on which the European parties are able to draw. The revolutionary movement depends almost entirely on a few advanced spirits drawn from the thin upper crust of Labour aristocracy. Owing to the heavy social disabilities and political backwardness the natives are not able to supply any active militants to the Communist movement. The immediate needs of white trades unionism, in which a number of our members are actively engaged, tends to throw the more difficult task of native emancipation into the background. The white movement dominates our attention, because the native workers’ movement moves only spasmodically, and is neglected. It requires a special department, with native linguists and newspapers. All of which require large funds, which are not available. The Jewish community, with its anti-war and pro-Russian sympathies, has given generous support to our funds. But as the revolution clarifies, this support is now confined to the Jewish revolutionaries proper.

It will thus be seen that the I.S.L. has a particularly heavy task falling upon the shoulders of a few militants who have stuck doggedly to it for over five years. The present writer, having also left Africa for the time being, feels it his duty to appeal for some reinforcement to the South African movement, and to urge that it should come more directly under the purview of the Third International. A few missionaries, revolutionists who need a spell of sunshine, would be very welcome. Primitive though they be, the African natives are ripe for the message of the Communist International. Speed the day when they too will march with “the iron battalions of the proletariat.”