A stimulating essay from Louis Fraina as he looks at graft in capitalism and the middle class cry against ‘corruption.’

‘Lobbying and Class Rule’ by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 21. October, 1913.

The righteous spirit, like God Almighty, is here, there, and everywhere. Its wonders pass all understanding. Its all-pervasive power is omnipotent; and if the cynic doubts, behold, even politics is being transformed. Norman Hapgood, bursting with ethical conceit, leads the Fusion cohorts against Tammany in the name of the “ethical spirit in politics”; and what matters it that the Fusion Committee set a new high record of vulgar, dirty politics? The politicians are truly inspiring in their righteous pose condemning governmental ungodliness and corruption,–doubtlessly obedient to a guilty impulse. Men steeped in political evil are cleansing themselves white in the blood of the lamb of righteous politics. A veteran scalawag such as “Col.” Martin M. Mulhall pillories himself and his employers as unscrupulous and systematic corruptionists; and does so in the interest of righteous politics-making good his righteous claims by selling his shame for $10,000.

Capitalist government in America now seems to be one damned investigation after another. And to show the progress of civilization, there are no Cassandras moaning through the shame of the exposures, but cunning knaves exploiting the righteous spirit for the conquest of political place and pelf.

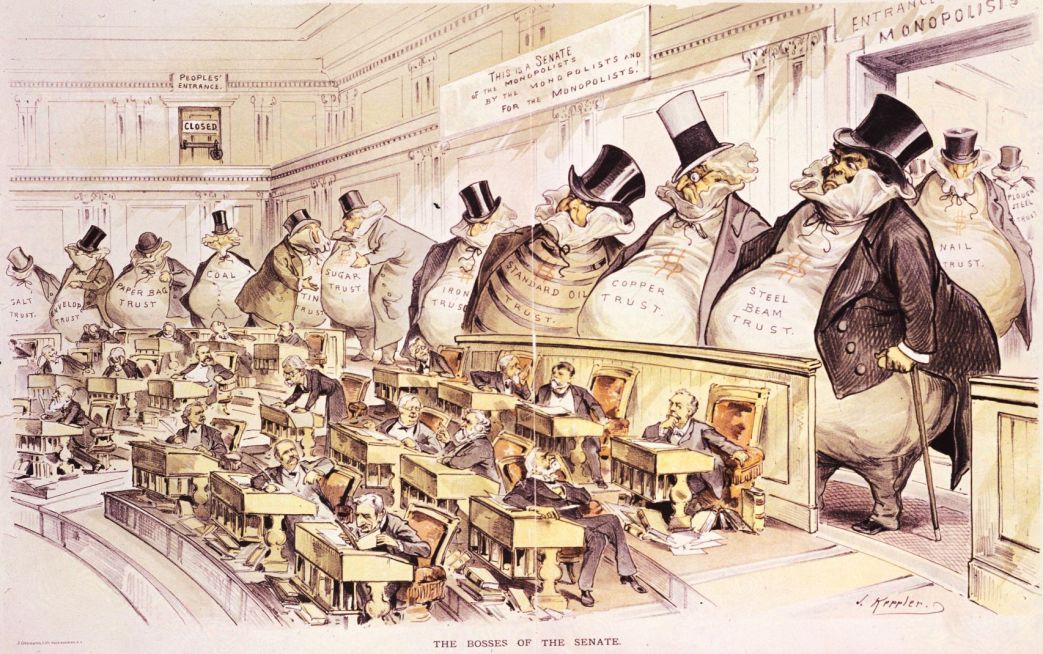

When President Wilson issued his broadside against the “insidious lobby” working to defeat his tariff bill, the Senate in a fit of moral indignation started an investigation. The investigation hadn’t proceeded far when overwhelming evidence led Senator James A. Reed, chief cross-examiner of the committee, to issue this statement concerning the activity of “the Interests”:

“One-They have opposed the election of men known to be opposed to their plans and desires.

“Two–They have secretly given aid and support, financial and moral, to those who have been subservient to their interests

“Three–They have carefully and secretly affected public sentiment through carefully prepared news matter sent out through press bureaus and otherwise disseminated through the press of the country.

“Four–With great skill, they have carried on a propaganda with their business connections and by this means sought to influence the votes of Congressmen.

“Five–They have maintained lobbyists in Washington whose business it has been not only to undertake to direct a course of legislation and to oppose all inimical legislation, but to undertake to control the election of the committees of Congress.

“Six–In one instance, at least, one of these interests, the woolen manufacturers, succeeded in having appointed, as confidential clerk of the Republican members of the finance committee of the Senate, the secretary of the Woolen Manufacturers’ Association, who performed his work so satisfactorily that he was presented by his employers, the woolen manufacturers, with $6,000.”

The lobby interests “raised and expended, directly and indirectly, for the purpose of controlling public sentiment and affecting legislation, many thousands of dollars.”

For a time, capitalist apologists found comfort in the belief that “the old-fashioned corporate representative who hung around legislative halls, armed with the all-powerful green-backs,” had disappeared. And then the Mulhall revelations showed that, while actual bribery may have declined, it was still practiced on an extensive scale.

The Mulhall exposure is a labyrinth of infamy and treachery. Its devious mazes lead from the manufacturers’ offices to the legislative halls, bribing, corrupting, pulling legislative wires.

Mulhall, as the field agent, of the National Association of Manufacturers, covertly bought the election of members of Congress obedient to its interests and fought those who were recalcitrant; “made payments of money to legislators who voted on bills as the Association dictated”; bribed minor labor leaders who acted as spies and strikebreakers for the N.A.M.; and bought employees of the House. The N.A.M. organized an adjunct, a paper organization, the National Council for Industrial Defense, for the special purpose of molding legislation and breaking strikes. At one time, President Van Cleave proposed raising $500,000 a year for three years to fight inimical legislation. The N.A.M. stands exposed as a widely ramified conspiracy against representative government, using the tremendous power of organized wealth in the interest of a capitalist clique. The vilest feature of all was not bribery, but the use of social influence, of political hopes, and the exploitation of ambitions and aspirations entertained by the men whom the National Association of Manufacturers wished to degrade into tools.

A novel and incriminating defense of the N.A.M. is that its officials were deceived by Mulhall. Undoubtedly; Mulhall’s testimony and letters show that he systematically lied to his employers. But the N.A.M. officials believed these lies, employed and paid and encouraged Mulhall on the basis of these lies. The N.A.M. reveals itself not only as an organized band of criminals, but as a rabble of gullibles. Cheating is ingrained in the bourgeois; he cheats and is cheated. The bourgeois is a dealer in gold bricks, and is himself an easy victim thereof.

Bourgeois radicals have inveighed against the trust-plutocracy as, in a sense, the only source of governmental corruption. And now here is the N.A.M., composed of manufacturers not allied with the trust-plutocracy, and most of them in opposition thereto, revealing itself as unscrupulous in political knavery as the trust-plutocracy. The petty bourgeois inveighs in reality not against corruption, but against the material interests which the corruption promotes. He uses corruption whenever necessary and effective for his own material interests.

Lobbying and corruption are not class measures; they are clique measures in the interest of one capitalist clique against another clique, or of the individual capitalist.

Lobbying and corruption have their basis in the multiplicity of conflicting interests within the capitalist class, as in the tariff controversy; in the temporary necessity of bribing legislators in an emergency, as when public indignation flares up at an outrage and threatens calamitous action on the part of honest or weak-kneed legislators; in the impatient desire of capitalists to grab immediately an advantage which could be secured without bribery in the course of economic evolution; in the individual capitalist seeking special privilege, as in the Allds’ bribery case in the New York legislature; and in the cunning of legislators aware of how business interests may be imposed upon and cheated, as in the recent Stilwell, scandal, ditto.

But corruption is no more a necessary condition of class rule than violence is a necessary condition of proletarian struggle. Both, in a measure, may be unavoidable, but they are not inherently necessary.

Corruption and the robbery of the public domain were big factors in building vast railway systems; corruption was a big factor in the formation and power of the trusts. Corruption thus plays an important part in plutocratic development; but that development would have been inevitable even without corruption, owing to the economic law of motion of capitalist society.

The United States Supreme Court was a mighty engine in the development of plutocracy. The Supreme Court has been remarkably responsive to plutocratic needs, setting the seal of its approval on some of the worst acts of economic brigandage. Two years ago the Supreme Court legislated the “Rule of Reason” into the Sherman anti-trust law; recently, it asserted, in the Minnesota rate decision, the supremacy of the federal government–both actions in the interest of plutocracy. Yet the Supreme Court has never been tainted with bribery. Social conditions, the spirit of the age, the inexorable logic of capitalist development, are the determining factors.

Government is necessarily government of the capitalists, and of the most powerful capitalists, the plutocracy. Economic power, and not corruption, determines control of government. Corruption helped to defeat Bryan and his middle class insurrection; but had Bryan triumphed, the economic facts and power would have restored the plutocracy to political supremacy.

Considering the multiplicity of investigations and the eagerness with which they are instituted, the innocent observer might conclude that things political were never as rotten as they are now, and that the future will see political purity enthroned. But the righteous spirit in politics is simply the last despairing protest of non-plutocratic capitalists against plutocratic power. When the recalcitrants shall have been bludgeoned into submission on the one hand by superior plutocratic economic power and on the other hand by a mighty Socialist movement, the righteous spirit will have become a phantom of the past. The middle class, more than any other class, translates its economic interests into terms of religion and morality.

The Rome of Nero was vibrant with the moral protests of the dying Roman spirit of old; and historians conclude that Nero’s reign marked the lowest depth of Roman infamy. Ferrero has shown, however, that conditions under succeeding emperors were even more rotten; but the old Roman spirit having been completely crushed, there were no more protests–the Roman Church acquiescing in and profiting by the infamy–and conditions retrospectively appear better. It now seems as if the United States would repeat that phenomenon.

Woodrow Wilson in the role of a Cato the Censor seeks to reintroduce the ideals and institutions of the Fathers. The ghosts of the old morality and democracy haunt plutocracy, but terrify it not at all. Roosevelt urges on his hosts at Armageddon; and impotent poetasters of reaction, such as Sylvester Viereck, hymn the Battle of the Lord. Behind the grotesque mask lurk and leer the petty bourgeois interests, which, once they make peace with the plutocracy, will profit by corruption and immorality.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n21-oct-1913.pdf