Life on the New York subway before it was organized by Transport Workers Union Local 100 in 1934.

‘Slaving for the New York Interborough’ by Patrick from The Voice of Labor (New York). Vol. 1 No. 2. August 30, 1919.

I AM a conductor on the –th Street street-car line.

At the barn where I turn in the nickels we have two unions-the Amalgamated Street and Electric Railways Employees, and the Brotherhood of Interborough Employees. If you are a member of the former you get fired, if you are not a member of the latter you are liable to get fired–for not washing! The Brotherhood is a real union; it started as a result of the great street car strike of 1915. The bosses started it. The men were striking for recognition of the Amalgamated, increased pay, shorter hours, etc. So the bosses thought to themselves: “Well if the men want a Union, they have a right to have a Union, and as Capital and Labor are partners, we must help them get it…”

Some Strike!

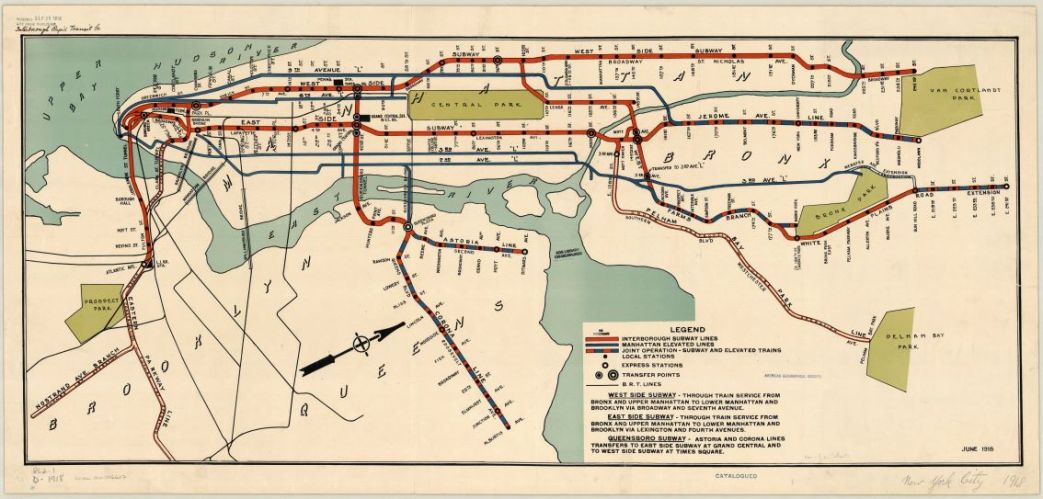

Recently the Brotherhood pulled off a strike, and believe me, it was some strike. The Elevated and Subways were tied up tight as a drum and we fellows on the street cars didn’t have to quit work for a single hour. There never was such a strike in New York. The Labor leaders could learn something from our strike. Not a wheel turned on either the Elevated or Subway lines for two days–except the wheels that carried enough cars to keep the city franchise. No arrests were made–why, there wasn’t so much as a picket seen during the whole two days.

This strike was very different than the ordinary strike. It was called by the Brotherhood president on the Company’s private wire. The Amalgamated offered to supply enough men to run the cars, just to prove it was a fake strike, and the Company refused. Under cover of the strike the Company fired about sixty men for belonging to the Amalgamated Union.

An Eight-hour Day

I have not yet got a “regular run.” This means that I get told each day what run I must take. I fill in when some fellow gets sick. Each morning I report for work at five o’clock and sit in the barn until I am called by the starter. Some mornings I get out by seven o’clock, and other mornings I sit around till nine; then the starter says I can go for the day. But a conductor or motor-man only gets paid while he is actually on the car, so on these days I get nothing. We are now getting 60 cents an hour, when we work.

For the men who have regular runs it is of course better. A man gets a regular run after about three months. But he gets last pick, and the runs at the bottom of the list are “long swing” runs, which means that they only go out in the rush hours. For instance, the fellow above me got a regular run a few days ago. He starts at 4.45 in the morning and works till 8 o’clock. By the time he gets his money and transfers “turned in” it is nearly 9 o’clock; he is then free until 12.30 p.m., when he goes on again and works for about an hour. He then “swings” until about 6 o’clock. From 6 o’clock he works until about 8.30 and he is finished for the day. For this day’s work he gets 8 hours pay. If there has been an accident or a long delay he has to make out a report, which usually takes him about an hour. But he only gets paid for the time actually spent on the car. If the time spent is 7 hours and 35 minutes, he gets 8 hours pay.

Seeing the Boss

In each barn there is a glass case in which a list of men who are to see the boss in the morning is posted. After waiting your turn you are finally admitted to the boss. Without looking up the growls: “What’s your badge?” (A street-car man is only a number).

“X—”, you reply.

After rustling through some papers he turns to you: “At 9 a.m. on Monday on a north bound run, at the corner of –th Street and –th Avenue, you accepted a transfer that was out of date. What have you got to say?”

You say whatever you think will get by, for of course you can’t remember what happened at that place, at that time, on that particular day.

“What do y’think this company’s operatin’ for? You’ll be takin’ cigar-coupons next. Two days on the list, and the next time you come in here you’ll be laid off.”

Two days on the list means that for the next two days you report at 5 a.m. wait around for four or five hours, and if not wanted are told to go home–thus losing two days’ pay.

Conductors and motor-men have to buy their own uniforms, from a store designated by the company. The uniforms cost around $18. A conductor has to “break in” for two weeks, and a motor-man usually takes six weeks before he is pronounced competent. During the breaking in period the recruit gets no wages.

The Silver Lining

The system of spying which prevails on the New York street railway system would make the Kaiser green with envy. The only way to get by is to assume that everybody is a stool-pigeon. Motor-men spy on their conductors, conductors spy on their motor-men. Men and women passengers are in the company’s employ and ride around for the purpose of spying. These plain-clothes spotters present bad transfers to the conductor, try to get past the box without paying a fare, enter into arguments for the purpose of trying to get the conductor annoyed, in order that he may insult them. They go to the front of the car and talk to the motor-man; if he answers back he is reported for talking while running the car.

But every cloud has a silver lining. The Interborough is not at all bad. It publishes a nice magazine which is distributed free. If one is a good employee he may get his name in print. If he has helped during a trying period, such as a strike, he may even get his photograph in the paper. If he has more children than any other man on the division then very probably the whole family will get its picture in the paper.

The Voice of Labor was started by John Reed and Ben Gitlow after the left Louis Fraina’s Revolutionary Age in the Summer of 1919 over disagreements over when to found, and the clandestine nature of, the new Communist Party. Reed and Gitlow formed the Labor Committee of the National Left Wing to intervene in the Socialist Party’s convention, eventually forming the Communist Labor Party, while Fraina became the first Chair of the Communist Party of America. The Voice of Labor’s intent was to intervene in the debate within the Socialist Party begun in the war and accelerated by the Bolshevik Revolution. The Voice of Labor became, for a time, the paper of the CLP. The VOL ran for about a year until July, 1920.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/v1n2-aug-30-1919-voice-of-labor-ocr/v1n2-aug-30-1919-voice-of-labor-ocr_text.pdf