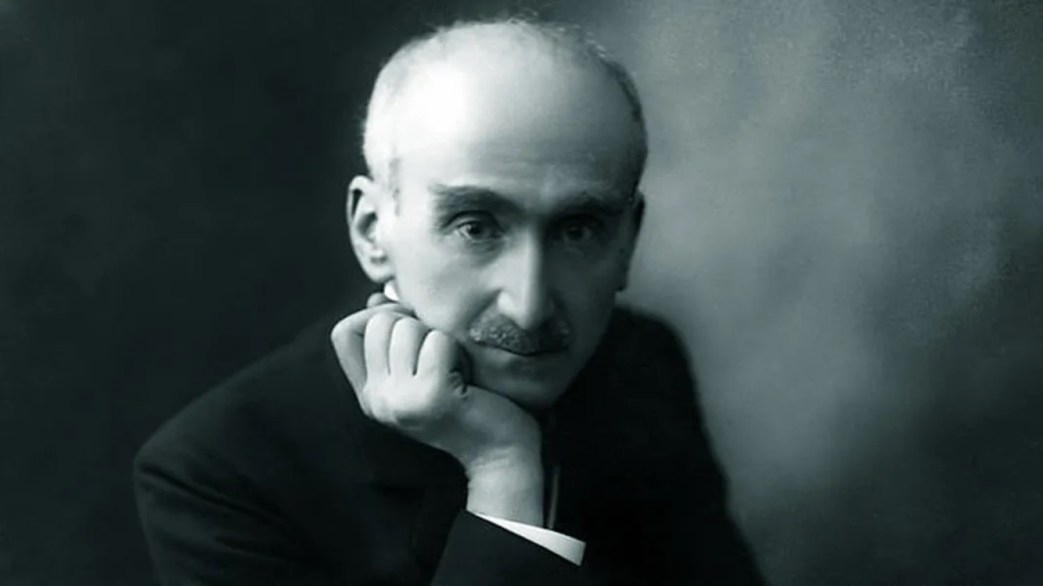

A marvelous exposition and critique of the ideas of French philosopher Henri Bergson, who posited that our experiences and ‘intuitions’ were better measures of understanding ‘reality’ than our ‘reason’, from another French philosopher, the revolutionary Marxist Charles Rappoport.

‘The Intuitive Philosophy of M. Bergson’ by Charles Rappoport from New Review. Vol. 2 No. 3. March, 1914.

I. THE FIRST PRINCIPLE OF THE BERGSONIAN PHILOSOPHY

It has frequently been said that knowledge consists of number and measure: to know is to count and to measure. Duration, time, seems to be as measurable as space. Bergson denies this. To his mind, and here we have the base of his philosophy, duration is not measurable. It is entirely a matter of intensity, heterogeneity, quality. To know, according to Bergson, is not to measure and to count. To know is to live, to feel within a duration, a pure intensity. which no human language can express except by symbols. Reason operates through notions, ideas, words, which distinguish, cut, reality into sections, setting off a series of disconnected moments, marking off the boundaries between objects. True reality is not created in the image of reason. Rational reality is an artificial reality created for the use of life, in the name of the utilitarian, practical principle. This artificial reality is labelled, classified, measured and counted. Reason does not consist in truth; it is only an instrument, a utensil of life, not life itself. Reality, life, is quite the contrary. It is an absolute discontinuity, an absolute heterogeneity, a thing to be contemplated in its entirety not from without but from within. Reality has no fixed contours, no definite frontiers. It is not composed of objects having the fixity, the solidity of statues. Reality is a flux, a flow, a process, an infinite movement to and fro. To understand reality, reason is powerless; intuition alone is able to approach it. Notions that are clear and definite divert us from the truth. Truth can only be lived, felt, through the light within. It can be expressed only by images. The musician, the artist, the one with his melody, the other with his symbol, are closer to reality than the scientist, who thinks he knows everything because he has bottled up life in a series of phials with a Greek or Latin label on each. Reality is an ocean which cannot be bottled up, nor is it to be dipped dry by the tea-spoons of human reason.

Reality is the immediate, the inexpressible, the unspeakable, the unutterable, in a word the experience of the irrational. That is why Bergson’s philosophy may be called the Philosophy of the Irrational, the Philosophy of the Immediate, or the Intuitive Philosophy. To term it the Subjective Philosophy would be to describe only one of its phases. For it insists that the intuition alone exhausts, absorbs, reality, while reason merely limits it, classifies it, categorizes it, determines it (this word comes from term in the sense of limit, end), in order finally the better to utilize it. Bergson says: “You have a right to say you cannot live without science. But do not say that science is life. Life is something you can never know, you can only live it. Life is an organism. Reason is a learned anatomist. Under its knife it holds not life, but a corpse, which it dissects with the aid of its own peculiar instruments, notions, number, measure, causality. The moment you begin to dissect life, life has ceased to exist. You imagine you are cutting in to the quick. You are wrong. You have before you only the membra disjecta of a reality one and indivisible.” Such, in our opinion, are the words Bergson addresses to the human reason. Reason and reality can never be reduced to an equation. Reason and life are incommensurable. Reason plays the part of a blind man striving to imagine the colors of the rose, of a deaf man striving to understand Beethoven. The intuition, looking upon the inside of reality, is alone competent. Intuition goes beyond reason. It enlarges, expands our capacity for understanding.

Such, roughly, is the directing motive of Bergson’s philosophy. To grasp all the finer aspects of his argument, he must be followed through the whole of his work, a work original in its form of expression and in its application, but not at all so in substance, as we shall proceed to show.

II. MOVEMENT, LIBERTY, PERSONALITY

If we cannot cut up reality, as the empiricists do, into bits that are measurable and numerable, we are likewise unable to compound it, as the defenders of the mechanistic theory do, by adding together its parts one by one. An organism cannot be formed by combining its anatomical parts. Bergson is a resolute adversary of the mechanistic philosophy, which believes it possible to compose a whole from the addition of the parts, a world from atoms and molecules, a personality by a summation of “mental states”, life from physical and chemical factors, memory from associated ideas. This is the procedure of the rationalistic method, which, like reason, works only upon the finite, the discontinuous, the fragments of reality. Bergson is anti-rationalistic. He contemplates, not the parts, but the whole. He synthetizes. Where the rationalistic method sees only the mechanism, the intuitive method postulates the organism, the living, active phenomenon, which cannot be separated into its parts without the risk of death, which has no fractions, and which, moreover, is a hapax legomenon, a thing occurring only once, never repeating itself. The intuition attains to the absolute. We have accordingly not a fixed, a cadaverous reality, but a reality living, moving, palpitating with life, rich in color, full of the ruddy blood of life, eternally young, eternally active.

Intuition is the direct, the intimate vision of things. The work of the reason may be compared to the impressions of a traveller, passing through a country which is strange to him both in manners and language. He sees the surface, the contour of things. He observes gestures, he hears sounds that to him are barely comprehensible. The work of intuition, on the other hand, is that of a compatriot, living the very life of his people, whose mysteries he divines and knows, whose every heart beat, whose every mental change he feels and understands.

To demonstrate his theory, Bergson frequently cites the example of motion, and reviews the fallacies, the sole purpose of which was to deny the existence of motion, under the pretext that every body in motion traverses an indefinite number of points, displaces itself; from which supposition was drawn the conclusion that at each instant the body was stationary on each point traversed. Bergson rightly observes that the fallacy consists in trying to create movement by using bodies at rest, that is to say, to form motion out of the motionless. Movement is a particular phenomenon which can not be broken up into parts. The moving body does in fact traverse the points of its line of motion, but it does not stop on the way. Motion cannot be accounted for by the motionless, any more than life can be reduced to the movement of the atoms, the organism to mechanism, liberty to determinism. At every stage of being, there arises a new fact, a new force, which, while resting on the elementary conditions of an inferior order, marks a progress, a leap into the unknown, an original movement, an urge (élan), a creation, an invention. Physics and chemistry are not enough to explain the phenomenon of biology. Matter does not explain mind. A knowledge of the determining causes does not reveal how the effect produced arose. The passage of life is marked by an X, an unknown quantity, a mystery.

This was said long before Bergson. M. Du Bois Reymond uttered, in regard to this same mystery, the famous apothegm: ignorabimus (we shall always be ignorant). Bergson brings in intuition and declares that this mystery of life is called “élan” “creation”, “invention”, “liberty”. For the moment, let us not criticise, let us not suggest. Let us go on with simple exposition. Bergson’s philosophy, in a word, is a dynamic philosophy Reality is for him entirely a matter of life, action, perpetual movement. Its dynamic character makes it inaccessible to reason. Reason, according to Bergson, is not supple enough, it is too rigid, too rectilinear, too static to attain with penetration to the dynamic, the eternal Becoming of reality. Reality is an eternal creation, not a creation ex nihilo, but a creation from given materials. It is a creative evolution.

III. REALITY AND ACTION

So then, the world of being, everything that exists, is divided into two parts: the world of intuition, replacing the thing in itself, the Noumenon of Kant; and the world of reason, a world necessary, but artificial. But why necessary? But why necessary? Necessary for action. Objects, cut out by reason from the indivisible block of reality, are only fulcra, centers of operation, loci standi, for the individual in action. Action creates from the solid, it solidifies the fused metal to forge of it instruments, utensils. Objects are the “schemes”, the “charts” of our action on matter. Matter itself is a fiction of reason, suggested by the need to act, the need to live. Being is a moving perpetual, where reason arbitrarily establishes stopping places, stations for the needs of the active life, for action. Language, by means of fixed terms, helps us to bring moving reality to a condition of rest. Words do not change, but reality is a constant change. That is why words never correspond to things. They are only symbols This is true likewise of the notions of reason, of our ideas. They are only the words of thought, words uttered in silence, in the language within. To return to movement, the moving body is not the summation of positions in space arranged one after the other. It is a new color, “it is quality itself, vibrating, so to speak, within, beating the time of its own existence in a frequently. incalculable number of moments” (see Matter and Memory, p. 225). Reason takes pictures, snap-shots, of reality, but the mirror of reality is always-we must never forget this point, according to Bergson–the intuition. The world, considered as the object of reason or science, is a world adapted, arranged, revised and corrected, or rather, deformed and distorted for the purposes of action. That is why conception, the concept, is always inferior to perception, the percept. For to conceive through the reason is to shorten, to abridge, to deform reality, while to perceive-always, of course, by intuition-is to arrive at the foundations, the “inmost heart” of reality.

Bergson has devoted special attention to dreaming, to laughter, and to memory, giving the results of his study in three works bearing these titles. These studies are so many stages in his development of the Philosophy of Action. The dream is made up of the fragments of shattered memory, which are reassembled in direct relation to the situation, the state of our body. “All our life is there, preserved even to its smallest details.” The dream is the passive reproduction of life. Memory, on the other hand, plays an active role. “What part does memory play in an animal organism?”, asks Bergson. And he answers: “Memory recalls the consequences, good or harmful, of a given action. In man, similarly, memory adheres to action. Our recollections form a pyramid, the apex of which pierces into our present action.”

The volume entitled Laughter is a remarkable study of the nature of the comic. At first glance, the question would seen to have no direct relation to Bergson’s intuitive philosophy; but on maturer reflection, one discovers a very intimate bond between the definition of laughter and the intuitive method of Bergson. Here is the definition: “What provokes laughter is a certain mechanical rigidity where we should expect to find the living flexibility of a person. He cites as an example a man falling down.”

If Bergson, who never laughs, at least in his public lectures, had a sense of humor, we might suspect that his definition of laughter was aimed at the mechanistic conception of life, the theory which sees only a corpse-like rigidity in the phenomena where the philosopher-psychologist sees all the rich suppleness of life, of action.

IV. A FRENCH HEGEL

Bergson, like Hegel, is an “obscure”, a difficult philosopher, in spite of his remarkable power as a writer. I consider him even more difficult than Hegel. For the difficulty of under- standing Bergson comes from the subject itself and from the very nature of his philosophy. Bergson, in fact, has a horror of clearness, distinctness; for distinctness presupposes isolation, classification, categories with fixed limits, definite outlines. All this is the business of reason, to which Bergson, a sworn enemy of rationalism, attributes a very subordinate role. However, intuition does not give up its secret too readily. The chosen field of intuition is the inexpressible, the ineffable. Its native element is reality, confused, plunged into an unfathomable, mysterious abyss. The pathways of intensity, that is, of pure duration, are not marked by sign-posts. Measure indicates no stopping places. The light of reason casts no rays through the shadows of the immediate. Bergson’s style is admirable; it is that of a great writer and a great artist. But, as an artist, the images, the symbols, by which he expresses himself, only double the difficulty, without hastening the solution of it. This imagery introduces one into the sanctuary of Bergson’s life; it fills one with a palpitation of beauty, surrounding one with enigmatic shadows, we might even say, with ghosts. But do not pretend, do not try, to understand. To do so, would be to betray the whole intent of Bergson’s philosophy, which is made up entirely of intuitions, of approximations, of tones, colors, sensations, of what the Germans call Erlebnisse, “experiences.” Bergson’s philosophy insists on being lived, felt: his lectures are laic masses, laic “services”. His hearers are worshippers. There is something distinctly religious about the atmosphere which pervades the Collège de France, Room VIII, on Fridays between five and six P.M., where a select cosmopolitan crowd packs in to listen to M. Bergson. I shall never forget one evening, when suddenly, during a lecture, the electric light went off. Bergson, with perfect composure, pronounced the simple words, “Let us not bother ourselves with such contingencies,” and went on with his lecture. Not a word, not an exclamation came from the throng packed almost to suffocation in the hall, and this audience was a crowd predominantly French, and accordingly, as is generally believed, inclined by habit to mockery and scepticism. It gave the impression of a multitude kneeling in prayer in the obscurity of a church. Outside thunder was rumbling, and flashes of lightening were sweeping the sky. But the audience saw nothing, heard nothing. It was elsewhere, soaring with M. Bergson in the lofty regions of pure intuition. If it was not the amor spiritualis Dei of Spinoza, it was certainly the intellectual passion, the thrill of logic and beauty inspired by the subtle fragrance of Bergson’s philosophy, which caused this miracle of transforming auditors into worshippers.

Like Hegel, Bergson has a Right and a Left. The conservative and reactionary Right clings to intuition, to the criticism of reason, to impenetrable mystery as a secret gate through which to introduce all the ancient beliefs, all consoling truths, God, Soul, Immortality, Absolute Liberty, Autonomic Personality. For such people Bergson is a new Messiah, sent by God to deliver the pagan world from two monsters, materialism and determinism. The Sun of Intuition enlighteneth the paths to the Infinite!

But Bergson has, or rather once had, a revolutionary Left, made up of the Syndicalists under the leadership of M. Georges Sorel and his disciples, MM. Lugardelle and Berth. The Syndicalists seized on the dynamic aspect, the action wing of the Bergsonian philosophy. Bergson brings everything back to action, “to an impulse which is the essence of life,” to thought which is active, to feeling which vivifies and creates. Revolutionary Syndicalism, or Syndicalism which has a revolutionary pose, tried at one time to appropriate this philosophy of action. It took the Syndicalists some time to find out that Bergson’s philosophy was, by the nature of things, by the logic of its anti-rationalism, the Philosophy of Reaction.

V. CRITICISM OF BERGSON

It is futile to attempt to drive reason out of philosophy. Reason does not submit passively to it: she at once asks the reason for her exile. When he cuts human nature into two parts, into intuition and reason, Bergson misunderstands the true nature of what he calls intuition and the true nature of Reason cannot be detached from intuition, for which we already have a satisfactory term, experience. Reason is only a moment, the culminating point, of experience. Experience obtains its immediate data by way of the senses, through the channel of real intuition, of what Kant calls Anschauung. But experience unrationalized, experience unformulated under the guidance of reason, is a chaos, an indescribable mass; experience or intuition, without reason, is blind. But reason, taken by itself, does not give reality; scholastic reasoning, reasoning on reason, made up of ideas and of forms, without the check of experience, of life, is a horrible vacuum. Knowledge is a complex process having at its base the direct contact of the environment with our senses, and at its summit the synthetic labor of the intelligence, which formulates laws.

By stripping reason of all content, Bergson has distorted its function, committing himself an act of arbitrary abstraction, of arbitrary classification. He has detached reason from its living root, from experience. He has himself been guilty of a rationalistic operation in the scholastic sense of the word. The whole progress of modern science consists in the negation of the possibility of conceiving reality by pure reason. Reason has recovered from the arrogant pretentions to omnipotence that characterized it in the Aristotelian period and in the Middle Ages. Since Bacon and the Renaissance, Reason makes no affirmations without “questioning Nature”. With Kant it claims only the role of the organizer of the immediate and material data of experience. The fundamental error of Bergson is to contrast reason with life and experience (“immediate intuition” or “direct vision”), whereas reason and experience simply complement each other, both together forming the rings of a single uninterrupted chain. Bergson in fact does not distinguish between reason-abstraction, generalized from formal logic and dealing only with relationships, and concrete, empirical reason, which is the last word of organized, methodical experience.

Bergson has not observed that in arbitrarily isolating from reality (which, to his own sense, is a unit) a fragment, which he then proceeds to reduce, to deprive of all content, leaving it only the aereous and transparent exterior of mathematical form, he falls himself into the same rationalistic errors which he is fighting. He mistakes his concept of reason for the percept of reason, taking reason-abstraction for reason-life. Reason is like the lance of Achilles: it cures its own wounds. Reason itself proclaims its own vacuity if it pretends to be sufficient unto itself, if it tries to make itself independent of reality, of life. The reason of modern philosophy, the reason of the New Organon, of the Critique of Pure Reason, excepting a few errors that were quickly perceived, has put an end to Reason-abstraction to make way for Reason-experience. Formal reason, reason-abstraction, may be compared to an empty receptacle, to an unfurnished room where nothing is to be seen but the walls; whereas scientific, experimental reason, is a receptacle that is full, a room well furnished and decorated.

And here is another fundamental error in the philosophy of Bergson. It is true that reality is an immediate, an All directly perceived by our senses and untranslatable into terms of pure reason, of reason taken by itself. But the contrary is not true. Every immediate is not reality, objective reality. The woman we dream of, the woman we live during slumber, has nothing in common with the real woman, except the name and the image. Likewise to imagine an Infinite Being who consoles us, who is useful to our psychological and moral comfort, to live this Being in the imagination, in the so-called mystic life, that is to say, beyond the control of reason, is not sufficient to make that Being really exist. The fact that you vividly pre- sent to my imagination a million dollars is not enough to make me a millionaire. Nevertheless the whole of pragmatism is erected on this sophistry, which subjects reality to the products of Intuition, intuition useful and stimulating, consoling and beneficent!

Let us give full permission to the pragmatist to go on his own credit, and, to resume our figure of the imaginary millionaire, let him view himself as a millionaire to his heart’s content. No banking house will follow him in his illusion even though that illusion be an illusion that is lived, a beneficent illusion, an illusion which endows with blessedness the pauper who creates for himself his imaginary wealth.

Intuition not controlled by reason is an arbitrary instrument, a sort of magic lamp of the Thousand and One Nights. It is no longer a question of philosophy, but of magic.

By excluding from the total experience its supreme moment, reason, Bergson goes back to the sophistries of the ancients, which held (1) that we know nothing, (2) that we can say nothing, (3) that we can understand nothing. The immediate, the inexpressible, the unspeakable must lead to absolute solecism. How can I, in fact, communicate to others the results of my intuition, absolutely detached from reason and from language? I am plunged into the abyss of confusion, of unconsciousness. No outlet is left upon life. There is no possibility of communicating with others. For the intuitive being is without reason, without a tongue. It exists only for itself, only by itself. It has no existence for the rest of us. So then, it has no existence at all.

Bergson may thus be refuted on his own grounds, by using the same rational method that he uses.

VI. BERGSON’S CONTRIBUTION

The part that will survive of Bergson’s philosophy, outside His is of his theory of quality-duration, is not entirely new. the dialectic method founded by Heraclitus and used by Hegel Marx and Engels. And if Bergson were addicted to citations, he might be criticised for not having mentioned his predecessors. Reality-change, reality-life, reality-action, is the indestructible basis of the Bergsonian philosophy. To this doctrine he has given an expression always artistic, always subtle, often original. But its substance was acquired long before Bergson.

Like all great metaphysicians, Bergson has an eagle eye for the defects in the metaphysical systems of others. He has criticised with keenness, and even with geniality, certain materialistic dogmas, certain materialistic errors, under the cover of which materialism was losing its efficacy as a method for research, and posing as a sort of master-key to all problems, opening every door, explaining every enigma, and believing itself the point of arrival instead of a point of departure. Bergson has taken the conceit out of the materialists.

VII. THE RETURN TO PURE RATIONALISM

But Bergson is blind to the nature of his own solutions. He does not see that in identifying life with impulse (élan), the absolute with intuition of pure duration, personality with flux, liberty with invention and creation, he is doing nothing but imitate the traditional metaphysics, which had the bad habit of concealing behind words our utter ignorance, of solving difficulties by inventing new terminologies. Bergson arrives at a conclusion quite the opposite of the one at which he aimed: he arrives at rationalism. He creates new notions, new ideas, which are offered as substitutes for new concrete solutions. He has restored rationalism to its ancient pride. Reason was getting tired of struggling with facts, of struggling with things. It was getting home-sick for its ancient self, the intricacies of pure reason. So Bergson went to see Plotinus. We are back again in the scholastic age.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1914/v2n03-mar-1914.pdf