Austin Lewis was the leading Marxist theorizing industrial unionism in the United States before World War One. Among his most important works, meant to become a book, were a series of articles on on the politics, economy, and psychology of ‘solidarity’ for the New Review. Here, he looks at the Wheatland hoppickers strike and finds ‘solidarity’ to be a material reality.

‘Solidarity–Merely a Word?’ by Austin Lewis from New Review. Vol. 3 No. 10. July 15, 1915.

DURING the trial of the Wheatland hoppickers at Marysville in Yuba County, California, in January, 1914, the word “solidarity” forced itself into notice almost against the will of counsel for both sides. The accused were undergoing trial for the murder of the district attorney of Yuba County. The official had been shot in a fracas attending the breaking up of a public meeting of hoppickers, who were protesting against conditions of employment which were subsequently held by the state investigating committee and public opinion to have been intolerable. Richard Ford who was credited with the leadership of the strike movement had made use of the word “solidarity” in one of his speeches. The special prosecutor, an able, though narrow, country lawyer, and presumably of fair education, stoutly asserted that the word “solidarity” was unknown to him. It cannot be known whether as a matter of fact his ignorance was real or assumed, for though he may have known the word himself he was clever enough to have been well aware that the jury did not know it. Later indeed he asked the jurors to view with suspicion those who used other than ordinary words. This brought a definition of “solidarity” from the counsel for the defense which evidently did not help his clients much for they were convicted. We may safely assume therefore that the word “solidarity” was unknown or regarded with hostility in Yuba County prior to the trial of the hoppickers.

About three weeks after the trial a great meeting of four thousand people or more was held in the Dreamland Rink in San Francisco. The audience had assembled to protest against the conviction and imprisonment of several active labor men, including the two convicted in the trial just mentioned. Among the speakers was a Unitarian minister who had come to the meeting from his evening service. His name was unfortunately a long way down on the list, he had come late, and the audience was anxious to hear a certain speaker. Moreover, it being Sunday, he had dressed carefully and in clerical attire. His long frock coat, polished shoes and air of ministerial precision were all too plainly not approved by the audience, which greeted him with cries for the name of the person to whom they preferred to listen.

It was quite a difficult moment for the minister. He conciliated the crowd by a few well chosen words and most of all by his statement that he would speak briefly. Then developing his thought in a few direct sentences he led up to the word “solidarity.”

The response was immediate, enthusiastic, indeed. All hostility was forgotten and the audience gave itself up to rapturous applause at the mere sound of the word and under cover of this applause the speaker cleverly retired.

Here was at once evident a striking difference between San Francisco and Yuba County. The difference explained at once how a laboring man of San Francisco charged with an offense in the course of a labor fight could not have a fair trial in Yuba County. It was at once clear that the actions of men who organized and struggled in the name of that unknown and hated word would be both incomprehensible and terrific to those who did not grasp its significance and the moral notions which lay behind it. Not to know the word “solidarity” was to be ignorant of the compelling notion which animated that crowd in the Dreamland Rink. Not to know and not to comprehend meant of necessity to be unfair. Affidavits of lack of prejudice would of necessity fail to convince any man that saw the trial and was present at the San Francisco meeting of the fairness of the Yuba County jury.

Still, the class from which the Yuba County jury was drawn was not essentially different from that of which the San Francisco audience consisted. The two sets of men were probably in the main educated under very similar conditions. Each had received practically the same training in civic and social ethics and they were not far apart in their respective stations in life. The local newspaper in Marysville had made somewhat of a grievance indeed of the fact that the prisoners and other “hoboes” who were in the courtroom made a better appearance than the majority of the small farmers and others summoned on the panel as prospective jurymen. There would probably be about the same percentage of foreign born in the audience at Dreamland Rink as in the jury. As regards general intelligence and alertness, both physical and mental, the “hoboes” had beyond all comparison the best of it. External differences between the groups were but slight as com- pared with the resemblances and a foreigner would have had great difficulty in making any rational or satisfactory differentiation.

All the jury had at one time or other belonged to the class of wage-workers. The small farmers had acquired their farms after a period of labor as employees and the dredger man, the gardener, and the union carpenter were actually engaged in manual work at the time of the trial.

But solidarity made no appeal even to the union carpenter, to the surprise of his fellow craftsmen in the city, who found after investigation that he was an organization member from compulsion and not from choice. The city radicals also pointed out with some emphasis that he had at one time been an employer and hence could not be expected to appreciate the significance of solidarity.

These explanations were, however, tempered if not destroyed by the knowledge that the trade organizations of Marysville had gone on record against the men on trial although the organizations in the rest of the state had generally taken steps in defense of the accused and had raised funds on their behalf. Moreover the Yuba County trade organizations had declared that the men would have a fair trial in their city, the possibility of which was scouted by the working class outside that locality. However the statement of the Yuba and Sutter County Building Trades Council was modified by a careful qualification. Their resolution ran as follows:

“Further, as far as the trials of the Wheatland suspects are concerned, whether they be members of organized labor affiliated with the A.F. of L., or I.W.W., or with no affiliation whatsoever, we have every confidence that they will have a fair and impartial trial, as the constitution guarantees in so far as lies within the power of the superior judge of the court.”

This may possibly be interpreted as merely a personal testimonial to the judge who was to try the case and perhaps was due to the fact that sons of the judge were members of the organization. But it does not alter the fact that the organization in Yuba and Sutter Counties refused to give either moral or financial support to the men on trial.

As an isolated instance of the lack of that solidarity which is so vehemently proclaimed as the necessary result of the trend of economic development the above might be interesting but not convincing. But it is really typical rather than exceptional and raises a question as to the actual existence of the desired solidarity.

Why did the Dreamland Rink audience applaud the word “Solidarity?” A few years ago it would have fallen idly and uncomprehended. Only lately has it become a commonplace of the platform.

In the nineties a San Francisco audience would have had the same difficulty in comprehending its significance as did the Yuba County unions and the Yuba County jury last January.

But of late the street corner orators of the I.W.W. and a multitude of radical writers and speakers have familiarized the working class public with the new term. Just as the Socialist agitators made the word “proletariat” “understanded of the multitude” so have the industrialist agitators made the word “solidarity” one of the phrases of the day in labor circles. So general has the word become and so familiar has its sound grown that its mere repetition is enough to provoke that applause with which the use of a well known and popular expression is always rewarded.

The Socialist theory of the class struggle with its final conflict between the two hostile classes of capitalists and workers involved necessarily the concept of the solidarity of the working class. The phrase has been bandied about until it has become almost sacrosanct by mere repetition.

In the early days of the Socialist movement a speaker was almost sure of applause when he used the expression “collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange” or the term “cooperative commonwealth.” Today the word “solidarity” is almost as effective. William English Walling in his Progressivism and After says:

“Working class solidarity has become an ideal not to be analyzed, a mystical dogma to be preached, but not to be explained…In a word working class solidarity is a perfect example of that very ‘ideological’ habit of thought against which the economic and class conflict interpretation was directed.”

The very expression itself does not mean what it would seem to imply. It all depends on the circumstances under which it is used.

If the term is employed during a strike in which the American Federation of Labor is engaged and which has created much local interest and the Central Labor Council of the locality has become actually identified with it, the significance is, that all the unions of the locality affiliated with the Central Labor Council are expected to show their “solidarity” by actually and actively supporting the strike. This is the most that it could mean under those conditions and, as a matter of fact, it might mean a great deal less. It certainly would not include the great masses of unskilled and unorganized labor. It might not even include the entire strength of organized labor in the locality, for the orators would not hesitate to use the expression, even though the jurisdiction and other intervening impediments might practically render it meaningless.

This is really the case in the majority of labor disputes. Owing to the form of organization the various elements on the labor side in the struggle are not brought into line and do not act coherently and simultaneously. Subsidiary and even cooperative branches of the same industry are not sufficiently cohesive to stand together and to maintain an organized common action against what would seem to the common enemy and, the attack falling upon the forces of labor piecemeal, they succumb piecemeal.

As a matter of fact the unions are frequently quite anxious to show that there is no solidarity and to avoid even the appearance of united action. The Union Labor Journal of Stockton, in an editorial written on the eve of the greatest labor conflict in the history of that city, says in its issue of July 11th, 1914: “As a matter of fact union labor never indulges in the sympathetic strike. The sympathetic strike as a practice of union labor is wholly a fiction. To be sure an allied trade may go on strike with another trade as the result of a difference existing between a common employer and the other allied trade but such strike is by reason of an agreement existing between the allied unions which makes a strike of both unions imperative. The existence of such an alliance between unions is always a matter well known to the employer.” (Italics ours).

It is clear that the term “solidarity of labor” can possess no significance for those who take this line of thought. The very expression “allied unions” implies organizations which find an advantage in united action, but this united action is by the very nature of the expression temporary and for merely practical purposes. An alliance is not solidarity. In fact, the term is in itself a negation of solidarity. If the special prosecutor of Yuba County therefore did not grasp the significance of the term “solidarity” he did not differ from many of the organized members of the trades even in the cities. For where the speakers of the latter use the expression, it is, as we have seen, with little comprehension of its meaning, and with practically no understanding of its ultimate and real significance. Indeed, the special prosecutor, with a sort of instinctive grasp of the facts, highly creditable to his perceptive faculties, set to work to accentuate the differences between the prisoners and the American Federation of Labor unions which had supported them financially and sympathetically. He pointed to the I.W.W. song-book and particularly to the song called “Mr. Block” to prove that the prisoners were members of an organization which ridiculed the American Federation of Labor and even spoke disrespectfully of Mr. Gompers. Here, indeed, he was in accord with many of the leaders, even in the unions which had come to the assistance of the accused.

The members of organized labor who had been trained in the old conceptions of trade unionism had really but little sympathy for these migratory hoppickers as workers, but the inhuman and detestable conditions under which they labored shocked them and appealed to their human sympathies. The State investigation and the testimony of respectable and unimpeachable witnesses had shown that women and children were wallowing in filth and misery, were deprived of water, subjected to the risk of disease and to penalties and discriminations against which even the conscience of the middle class revolted.

The agitation of the middle class in the Wheatland affair will compare well with that of the unions except in the very necessary matter of raising funds. Civic centres, churches, women’s clubs and other organizations of a social or civic character, took an active interest in the case. A group of university students under Dr. Parker, the executive secretary of the State Immigration and Housing Committee, gave careful and enthusiastic attention to all the circumstances surrounding it. Mrs. Inez Haynes Gillmore, a famous writer of fiction, published an excellent article in Harper’s Weekly (April 4, 1914). Women interested in public affairs, like Mrs. Lillian Harris Coffin and Mrs. George Sperry, went to Marysville to watch the trial in the interest of humanity and fair play, just as did Miss Maud Younger, whose efforts have always been put at the disposal of the working class, and Miss Theodora Pollok, who worked indefatigably. Other women, even at Los Angeles, five hundred miles from the occurrences at Wheatland, busied themselves in preparing and circulating petitions and did all in their power to create an agitation in favor of the accused.

So that it could not be said that the agitation on behalf of the hoppickers was essentially an example of the “solidarity of labor” of which we hear so much and see so little.

The fact remains, however, that in spite of all misunderstanding and ignorance the word “solidarity” is a term of increasing potency. Apart from its effectiveness as a rhetorical expression the labor fight is sometimes actually carried on in terms of solidarity when otherwise no basis for united action could be found. Thus to refer again to the particular case which we have under consideration.

During the agitation on the Durst hop-ranch the Japanese workers voluntarily threw in their lot with the rest of the workers. The spokesman for the Japanese stated, rather astutely, that it would probably not be for the advantage of the white workers for the Japanese openly to espouse their cause and strike with them. By this he meant that the feeling of the working class against the Japanese was so general throughout the State that the association of the Japanese with the strikers would in all probability be detrimental to the latter. He said that in order not to embarrass the situation for the projectors of the strike the Japanese would withdraw from the field in a body, which, as a matter of fact, they did.

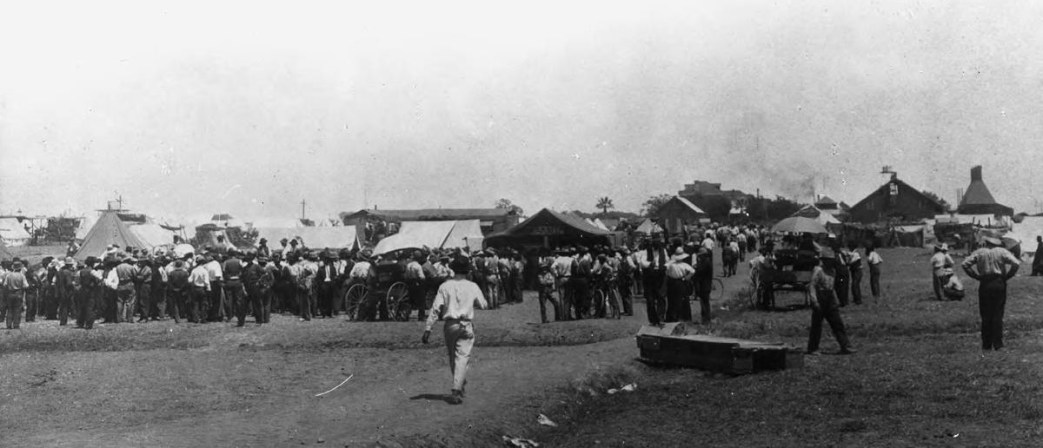

The same spirit pervaded the entire mass of the employees on the Durst ranch, and according to the testimony of a gang-boss employed in superintending labor during the hoppicking season, no less than twenty-seven languages were spoken by the workers. Syrians, Porto Ricans, Mexicans, and a heterogeneous collection of races and breeds left work simultaneously, and were a unit in support of the demands of the strikers.

This was no slight matter, for the majority of them were practically penniless; they were far from the centres of population, and to leave work meant, in many cases, to go hungry. To them solidarity was an essential fact of life.

Being unskilled workers and not having any special craft, trade, or property on which they could depend, they were driven to rely upon mass action for life and for protection against the aggression of the employer. To them, therefore, “solidarity” expressed not an ideal, not a distant goal, not a political achievement, as to the Socialist, but that mass-action to which they were necessarily driven and upon which they could alone rely.

Shall we say then that “solidarity” is incomprehensible except to those workers to whom mass-action is imperative?

Such an answer would be close to the facts, for the meaning of “solidarity” can only be learned by experience.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n10-jul-15-1915.pdf