A fascinating report on the industry where all work is defined by gender and ethnicity from the Women’s Trade Union League

‘The California Fishing Industry and Its Women Workers’ by Elsa Lissner from Life and Labor (W.T.U.L.). Vol. 11 No. 5. May, 1921.

COMMERCIAL fishing in California centers principally around the bays on the west coast, those of San Francisco, Santa Cruz and Monterey, to the south at Los Angeles Harbor and San Diego and on the northwest, at Pelican, Humboldt and Mendocino. The industry is divided into two branches, one for which the fresh fish market is the outlet, the other, the canneries. Most of the fishermen who catch for the fresh fish markets on this western coast own their boats and equipment. According to the California State Fish and Game Commission, there are over 50 varieties of fish caught. Scarcely one-fifth, however, goes to the fish markets. Those who catch for the canneries possess the boats and nets, also, in some cases, and contract for the tonnage they bring in. However, it is a common thing for the canneries to finance the fishermen. Certain sums are withheld from the value of the catch to apply against the loan. Sometimes the cannery owns the boat and the fishermen the net. In this event, the method ordinarily pursued is to divide the value of the catch. Since the crew consists usually of eight men, there are ten shares to a catch, eight for the men, one for the net and

one for the cannery, first deducting a part for the fuel expense. When the cannery owns both the boat and the net, two shares are withheld by the plant.

Organization among the fishermen is that of cooperative association made up of those nationally similar. The principal associations are the Italian, the Austrian and the Japanese.

Among the cannery workers, men or women, there is no permanent union organization for those employed in California. The men who work in Alaska in the salmon fishing are recruited in San Francisco, the Alaska Fishermen’s Union having its headquarters there. They are enlisted in the spring to work during the salmon run of the summer, which lasts only eighteen days. Conferences between employers and representatives of this union take place in San Francisco before the opening of the season in Alaska. The agreement is drawn up by which the terms of employment are specified. Although there have been no strikes, wages and conditions of labor have been materially improved since the formation of the union in 1902. Wages have increased gradually from $50.00 for the season’s run to $200.00 in 1920. There are about 4,000 members, longshoremen, sailors and fishermen as well as men who can turn a hand at any of these jobs. Fishermen in Alaska have to be Jacks of all trades, but none of these men is employed in the canneries for which the fish are caught, nor are any women employed. Chinese, Mexicans and Japanese work in the plants.

In California, there have been sporadic attempts at organization among the fish cannery workers. The women have joined with the men when such organization has taken place. This has been mainly in the Monterey district, the union being a temporary one during a strike for increased rates of pay. One such strike during the 1920 season resulted from the introduction of a scaling machine into some of the canneries, scaling having been a hand operation before this. The strike brought about adjustment of the piece rates.

All nationalities are included among the fishermen, Japanese, American, Italian, Austrian and Slav predominating. The Americans may be, of course, naturalized citizens of other countries. In a report to the State Board of Control by the State Fish and Game Commission it was estimated that in the south (south of San Luis Obispo) about 55 per cent of the fishermen are Japanese and that they bring in about 85 per cent of the catch. In the Monterey district, the fishermen are mainly Italian and Japanese and in the southern centers they include Austrians also. Generally speaking, it is the Italian who catches for the fresh fish markets, the Italian, Austrian and Japanese for the canneries. In the south, there are many Austrians who have migrated within the last two years from the Puget Sound region because of the scarcity of the salmon there.

The Japanese use the hand line method of fishing and catch all the albacore, which is the commercial tuna having the desirable white meat. Since the Japanese is the only one who uses this vastly more difficult and tedious method of hand line fishing, and since the albacore, with greatest trade value. can be caught only in this way, the canner has encouraged the Japanese fishermen. The blue fin and yellow fin tuna are brought in by the Austrians, who use the purse seine net. During the 1920 season there was considerable loss by damage to nets because of the unusual size of the tuna fish, principally the blue fin. It is said that some of these fish weighed as much as 100 pounds.

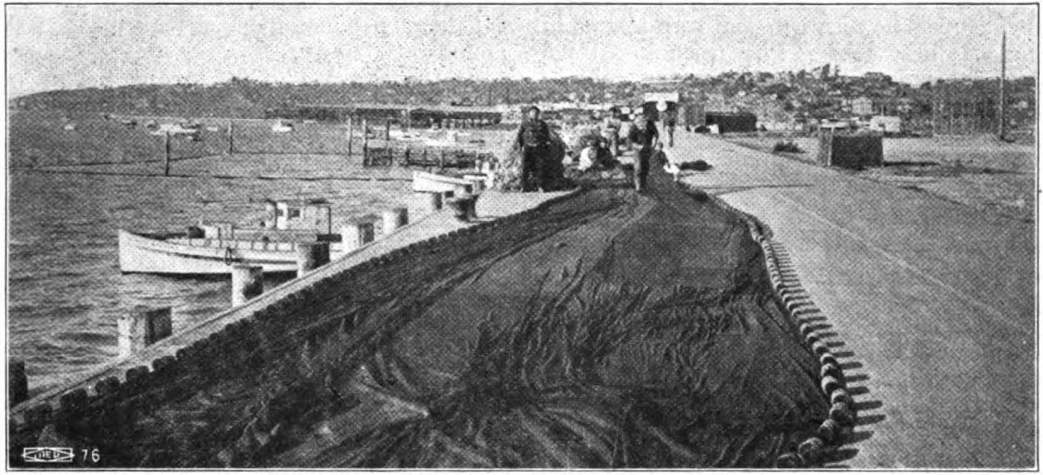

The net most used for sardine fishing is the lamparo or circle net. This was introduced into California by fishermen from southern Europe, replacing some forms of purse seine. With the lamparo, the fisherman circles the school of sardines, drawing it closed over the catch. Since the nets cost from $2,000.00 to $5,000.00 apiece they are tended with great care. It is a picturesque sight, a net spread along a wharf where it has been dried and the fisherman squatted at his weaving with his box of mending twine and his shuttle, singing an old tune of preoccupation.

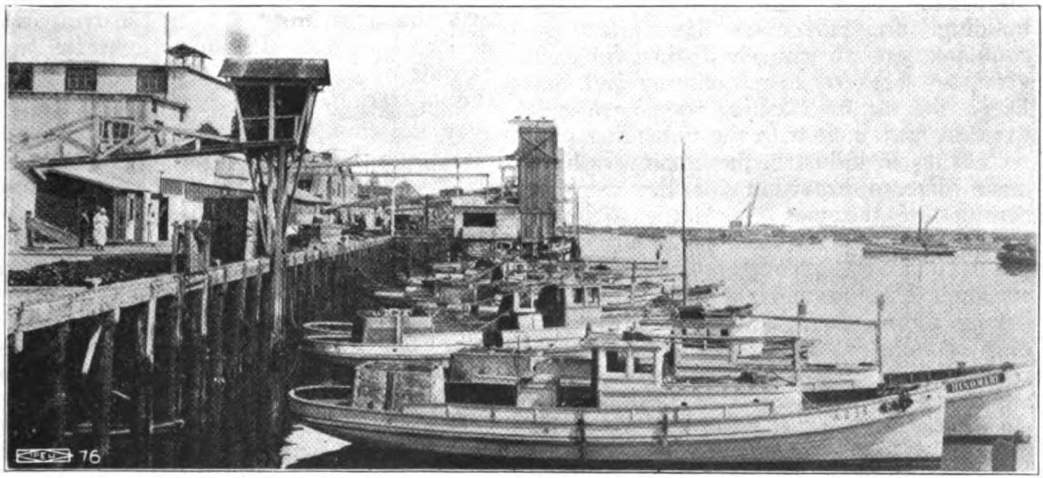

THE fishing boats come in with their loads usually at night. However, one day at East San Pedro, the writer watched them put ashore at noon. These boats were manned with Japanese fishermen. They tied up at the unloading pier of one of the canneries. There is a protected area here, a small part of the Los Angeles harbor, formed by a breakwater which affords a suitable location for the fish canneries. From the deck of the boat the fishermen shoveled the fish with a tool that resembles a tennis racket, somewhat wider and with a longer handle.

They threw the fish with this net shovel into a box which was lifted about 20 feet and turned onto a conveyor by which the sardines were carried into the cannery. There was much movement and activity. Hundreds of sea gulls, chattering and scolding, and many pelicans, snatching and flapping, gathered to snap a dinner from the water into which the sardines had spilled. The more daring gulls hovered over the boat and even lighted on the moving conveyor. There were four boats in this fleet. One, already unloaded, was being dragged of its net. Four Japanese, on the wharf, pulling sturdily upward, piled it on the truck to be taken where it could be dried. The Japanese in the boat seven or eight feet below, in his green sweater and bright woolen cap, straightened the net as the others pulled and folded, picking out the seaweed and the fish caught in the net, shaking out the tiny ones still clinging. Unloading a boat of silvery, slippery sardines seemed a hopeless, endless task; the fishermen started gallantly but stopped after a while, panting. It takes about an hour to unload the average catch.

There is comparatively little salmon canning in California. The salmon, at one time, were caught and canned when they came up the rivers to spawn, but at the present time the fishermen go out to sea and fish with line and tackle. The salmon in the Monterey district is no longer packed because it is too light in color, the deeper pink being commercially more desirable.

According to the State Fish and Game Commission, the estimated wholesale value of last year’s (1920) total fish pack in California exceeded nineteen million dollars and numbered 1,941,984 cases.

In the San Diego and San Pedro districts the pack is largely tuna and sardines. In Monterey, the main product is sardines. It was in this district, about twenty years ago, that sardines were first canned in California. On the northwest coast, only salmon is packed.

The only branch of the fishing industry employing women is that of fish canning. There are 52 fish canneries in the state employing normally about 3,800 women. Twenty-five plants pack both sardines and tuna, 8 pack tuna only, 14 pack sardines only and 5 salmon. Women’s work consists in cleaning fish and in packing or filling cans; in the salmon canneries, of packing only. The sardine branch requires in normal times about 2,500 women, the tuna about 3,000 and the salmon between 250 and 300. These women are Italian, Mexican, American and Japanese. In the Monterey district, for cleaning sardines the women are almost exclusively Japanese. This is the case also in the San Pedro district, which embraces the entire Los Angeles harbor region, Long Beach, San Pedro, East San Pedro, Wilmington and Terminal Island. In the San Diego district where there are comparatively few Japanese women employed, cleaning is done by Mexican and Italian. women. In the preparation of tuna a few Japanese women in the San Pedro district work at cleaning. Almost all the women employed in the operation of filling the cans are Italian or American. In the salmon plants in the northwest, Indian and half breed women are employed.

THE women who work in the fish canneries ordinarily live in the town in which the plant is located. There are not many who migrate for the season as they do to the fruit and vegetable canneries of the state. The exception is East San Pedro, where some of the plants provide living quarters for the fishermen and for the cannery workers. Part of this village is entirely Japanese, its nets spread in the streets, its children playing circumspectly in the sand and the glaring sunshine. Along the channel are many Japanese fishermen’s houses also. As on his own waters, his tiny house is built on piles, with a few inches of the porch devoted to bright flowered plants and green vines which overhang the smoky gray tide waters. Some of the workers live across the channel in San Pedro itself. They cross on the ferry, which takes about three minutes and which is run by a young woman who swings the rope like a cowboy when you tie up at the wharf at either end of the trip.

THE fish canneries range from the roughly built old wood or corrugated iron building to the modern concrete structure. In the Monterey district, the buildings fringe the bay, clustered quite closely together. With a background of historical California of memories, adobe buildings and of rolling hills, they are situated between the Fort of Monterey and the bay, the fishing fleet bobbing in the foreground. It is here that stories of vendettas and hot blood are told, for the fisherman and his women folk are largely Sicilians. The cannery buildings of best outward appearance are in San Diego. The plants there are scattered in three groups at far reaches around the bay. Those built close to the new Municipal wharf are modern, well equipped and attractive factories of gray cement and green tiled roofs, with flowers and vines and window boxes.

When a canner is working there is always the inevitable and hungry sea gull circling the unloading pier. At East San Pedro, one plant adjoins the other, facing Fish Harbor and the shipyards and the battleships anchored in the bay, with the Japanese village at the back.

The different operations of fish canning are usually performed in separate parts of a building. In many cases, the sanitary accommodations are entirely distinct for each group of workers. In Monterey and San Diego, the sardine cleaning rooms are built over the water close to the unloading pier. As always in industry, the employers have made diverse provision for the working comfort of the women. Some of these rooms are drab and cheerless, with wind and drafts leaking through the cracks. Some are built encouragingly next to the warm drying room. In other districts, the sardine cleaning room is merely one work- room distinct from the others. Occasionally, in the tuna plants, the cleaning and packing is done in one large room, as is so often the case in the fruit and vegetable preparation. It seems to be the custom, however, to keep them separated.

In the process of cleaning tuna, the fish are cooked and then cooled over night. After this they are brought to the women to be cleaned. The fish are headed and roughly cleaned by the fishermen before being brought to the cannery. The cleaner places the fish before her on the table, which is usually zinc covered and flat topped, although occasionally there are shelves for placing the baskets. She first scrapes away most of the skin with her knife and then by inserting her fingers in the side breaks. it lengthwise. She removes the strong back bone and the fish splits into four pieces. Then she rests a quarter on her left arm while with the knife in her right hand she scrapes away the brown meat, the white meat being kept as nearly whole as possible. This often makes for shoulder muscle strain for the beginner until the muscle hardens to the work. The fish, two, three or four on a wire tray, are brought to the women by the men. At the side of each woman is usually the refuse barrel into which the skin, black meat and bones are thrown. The cleaned fish is carried away also by the men, the women doing no lifting. The filling crew or packers show more tendency to sit at their work than the cleaners, there being considerably less body sway necessary. The cleaned fish is brought to these women and they cut it in slices. One or two of these pieces is fitted into the can and the remaining space filled with the small broken pieces. The empty cans are brought to the packer either on trays or by means of conveyor and the filled cans are taken away in a similar manner. As in the fruit canneries, the woman who is careful and capable of judgment is the one sought for this operation.

In the canning of sardines, the process starts for the women with the cleaning of the raw fish. Most canneries have machinery which scales the fish first; in some few, this is still done by hand. The sardines come first to the cleaning or cutting table, which is generally trough-like and partly filled with water to keep the fish from bruising. The women work so fast that they splash the water over the floor, so that the process is a very wet one indeed. All canneries, however, have racks on which the women stand and for the most part they wear rubber boots and rubber aprons. A few plants use a cleaning table which is comparatively dry in its application. It is flat, with strips of wood dividing each worker’s place. The fish comes to the woman by conveyor and by means of the trap gate she can control the amount of fish on her table. At the cleaning table, the head is removed and the entrails pulled, an operation that is done by experienced workers in one motion and with incredible swiftness. From this table, the fish pass through hot air boxes, where they are dried. They are then usually fried in olive or cotton seed oil, and after cooling for several hours they are sent to the packing tables. This part of the process, like most packing processes, is a careful operation. No fish may be broken, even the smallest bit, and, of course, they must fit into the can without jamming.

In canning salmon, the only part of the process in which women are engaged is that of packing, the remainder being entirely one of machinery.

At the present time, there is great irregularity in the matter of hours in the tuna and sardine branches of the fishing industry. There is also a lack of continuously steady work. There is less of this in tuna packing than in that of sardines. The tuna fish is cooked as the first step in the process and after that may be kept without spoiling for about three days, so that regardless of the hour they are brought in, the work of the women can be performed during the day. However, there is not always a steady supply of fish available. With the sardines, it is very different. According to fishermen, no sardines are caught during the bright or full of the moon unless there happens to be a fog. This makes it impossible to work continuously throughout the month. In addition, the fish taken at night must be brought in at once since they spoil after being out of the water within a few hours. They must be cleaned, therefore, with as little delay as possible. This necessitates night work for women in the sardine canneries, the factory whistle calling them to the task when the boats come in with the catch.

FOR the protection of women in industry in California, the Industrial Welfare Commission was established by the legislature of 1913, being one of the so-called “ten commandments” of the administration of Governor Hiram W. Johnson. At the present time, the members are A.B.C. Dohrmann, chairman, Alexander Goldstein, Walter G. Mathewson and Mrs. Katherine Philips Edson, executive commissioner. The Industrial Welfare Commission was one of the commissions which provided in various ways for the protection and welfare of the worker. It was part of a program of social legislation for which Governor Johnson was responsible. The commission exercises. legal jurisdiction over the work of women and minors in industry. It is empowered to call wage boards and establish a minimum wage in any industry in which women or minors are employed. At the present time, its orders cover ten industries and it has issued two sanitary orders in addition.

The minimum wage is based on the least cost of living for a self-supporting woman, with the standard one of maintenance adequate to supply “proper living and maintain health and welfare.” In common with the orders regulating several other industries the commission, in the fish canning industry, sets the minimum or least wage which may be paid to experienced women and minors. Apprentices are allowable, but the minimum rate is set for them also. In other industries the number of apprentices. is restricted to 331 per cent of the total number of women employed. In the fish canning, there is no limitation but a rapid promotion in the wage scale until the experienced rate is guaranteed at the beginning of the fifth week. The first order regulating the fish canning industry was issued in November, 1917, and provided a minimum wage of $10.00 a week. This was amended in June, 1919, with the minimum rate raised to $13.50 a week. In May, 1920, the order was further amended and the minimum rate set at $16.00. This is effective at present. The order also restricts the hours of labor to eight in a day, with the weekly number limited to forty-eight, but allows for overtime because of the high perishability of the product which is handled. The minimum rate for this overtime or emergency work is rate and a quarter.

Almost all the work in the fish canneries is on the piece rate basis. This is permitted provided the legal time rate set by the commission is guaranteed. The Industrial Welfare Commission also provides in this order that work performed after 10 o’clock at night and before 6 in the morning must be paid for at not less than rate and a quarter of the legal minimum rate. It also requires that where a full week’s work of forty-eight hours of regular time is not supplied, an increased hourly rate must be guaranteed.

Much progressive work is being done by the canners for the improvement of working conditions and the more efficient handling of the product which, of course, tends to such improvement. An endeavor is being made to find a method by which the sardines can be held longer without spoilage so that night work may be eliminated for the women workers in the canneries. The canners have tried also to find methods by which the supply of fish can be regulated so that continuous work may be provided. In this connection, an interesting experiment was tried lately. Through cooperation between the canneries in San Diego. the office of the State Fish and Game Commission and Captain Spencer, Commander of the Naval Air Station at North Island. sea planes were used for sighting the schools of fish. Through wireless communication the canneries or fish markets were notified when a school was located. It was found that this scheme helped to eliminate the uncertainty of employment in the fish canneries arising from the inability of the fishermen to locate schools of fish by the older methods.

On the whole it may safely be said that standards of work and wage for women have risen steadily and surely in the fish canneries in California.

Life and Labor was the monthly journal of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was founded by the American Federation of Labor, which it had a contentious relationship with, in 1903. Founded to encourage women to join the A.F. of L. and for the A.F. of L. to take organizing women seriously, along with labor and workplace issues, the WTUL was also instrumental in creating whatever alliance existed between the labor and suffrage movements. Begun near the peak of the WTUL’s influence in 1911, Life and Labor’s first editor was Alice Henry (1857-1943), an Australian-born feminist, journalist, and labor activists who emigrated to the United States in 1906 and became office secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago. She later served as the WTUL’s field organizer and director of the education. Henry’s editorship was followed by Stella M. Franklin in 1915, Amy W. Fields in in 1916, and Margaret D. Robins until the closing of the journal in 1921. While never abandoning its early strike support and union organizing, the WTUL increasingly focused on regulation of workplaces and reform of labor law. The League’s close relationship with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America makes ‘Life and Labor’ the essential publication for students of that union, as well as for those interest in labor legislation, garment workers, suffrage, early 20th century immigrant workers, women workers, and many more topics covered and advocated by ‘Life and Labor.’

PDF of issue: https://books.google.com/books/download/Life_and_Labor.pdf?id=z5NZAAAAYAAJ&output=pdf