A major report and analysis by Louis C. Fraina of the drama in Germany during March, 1920–the reactionary Kapp Putsch and subsequent Communist risings. Fraina was a witness to these event, being in Berlin while attending the congress of the Comintern’s Amsterdam Bureau. While ending with a ‘to be continued…’ I have not been able to find subsequent articles.

‘The Counter-Revolution in Germany’ by Louis C. Fraina from The Communist (Old C.P.A.). Vol. 2 No. 7. July 1, 1920.

Berlin March 28. THE Ebert-Noske-Bauer Government, shorn of Noske and Bauer, is again in power. The streets are still a mass of barbed-wire, entanglements erected by the counter-revolutionary troops against the Government and now used by the Government against the revolutionary masses; Government troops, armed with rifles, and sheath-bayonets hand-grenades, patrol the streets prepared to shoot down the workers (scores have already been shot) the identical troops that did not fire a shot in defense of the city against the counter-revolutionary invasion of Luttwitz-Kapp. The old apathy is again dominant in the streets of Berlin–that cold, hopeless apathy which immediately impresses the observer in Germany. In the “high life” districts, in Unter den Linden and Friedrichstrasse, the swirl of frightful gaiety again rushes on; while in the proletarian districts there is sullen resentment, tempered by partial anticipations of a new struggle.

Five days ago it appeared as if this new struggle might start immediately. The proletariat of Berlin was still on strike, in spite of the Ebert Government and the trades union bureaucracy having issued orders to end the strike. In city after city the workers used the opportunity of the crisis to usurp power, developing the General Strike beyond the limit imposed upon it as a strike in defense of the Government. In Westphalia and the Rhineland, in the Ruhr mining districts, the working class, while not yet wholly clear on means and purposes, was in complete control, seizing government power and organizing an active Red Army of 30,000 men, with 50,000 in reserve. But, for reasons which will develop later, these hopes are now a thing of the past; the Government is preparing an offensive against the Red Army, which has been compelled to accept an armistice: disaster and massacre will come in the Ruhr.

These are the inescapable facts of the situation: the Ebert Government is in power, but the military coup d’etat has partially conquered since it has compelled the Government to compromise and move more to the Right; the Government is withdrawing its concessions, or rather its promises of concessions to the masses; the interests behind the military coup are securing concessions as against the proletariat which rallied to the Government’s defense; the Government is compelled to rely more than ever on military force; while the Cabinet is being reconstructed according to the policy of the Right and not according to the demands of the Left. The proposal of the Independent Socialist Party for a “Socialist Government” (Cabinet coalition of Independents and Social Democrats) has been contemptuously rejected a rejection accompanied by a new Terror. The Socialist-bourgeois Government having and choose between the proletariat and the reaction, again chose reaction. The revolutionary crisis produced by the military coup, developing conditions for the final struggle for converted power, is being into a Cabinet-parliamentary crisis, with the Independent Socialist Party manipulating the situation to secure Cabinet concessions and parliamentary power: the Independents having, all through the crisis, acted not with an eye to the revolutionary seizure of power, but with an eye to (1) the reconstruction of the Cabinet on a “Socialist” basis, and (2) the coming elections in which they anticipate becoming the majority Party; while the Communist Party of Germany (as represented by the Reichs-Zentrale) is assisting the conversion of the revolutionary crisis into a parliamentary crisis by not measuring up to the requirements of the situation and by rendering criminally opportunist encouragement to the Independents in their proposal for a “Socialist” Government.

And the masses? The masses are stirring uneasily, baffled and betrayed; and they may yet, under the pressure of events, initiate a new struggle, compelling the hesitants and the moderates to accept revolutionary action.

1. The Collapse of Democracy

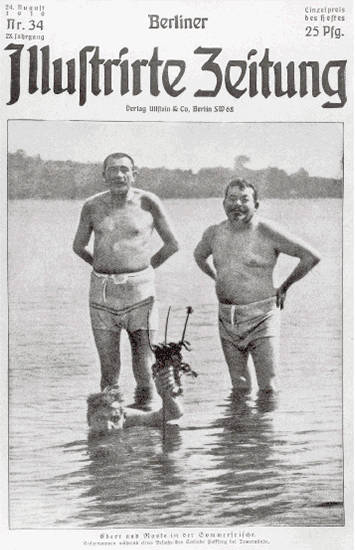

The Ebert-Bauer-Noske Government was directly responsible for the military coup d’etat. The coup was made by troops recently returned from the Baltic provinces, where the Government allowed a concentration of the most reactionary troops of the old German army for use against the Revolution and against Soviet Russia troops which, with the connivance of the Socialist Government, surreptitiously assisted Col. Avalaff-Bermondt in his counter-revolutionary campaign against Petrograd. The coup had been discussed for months and open preparations made; but the Government did nothing. On March 11 General von Luttwitz met President Ebert in Conference and issued an ultimatum, but von Luttwitz was not placed under arrest; while Noske, actively or compliantly, allowed the reactionary troops to prepare their coup. Late in the evening of March 12 Noske issued a statement that the fears of the Left concerning a military coup were unfounded six or seven hours later 10,000 troops invade Berlin to the strains of martial music and the plaudits of a crowd; the Government troops firing not a single shot in defense of the city, while the Government itself fled in an automobile…

There was no power of resistance in the Government–no resistance in democracy and the parliamentary regime. Aggressive and relentless against the proletarian revolution, the Government was weaker than woman’s tears against the counter-revolution. Democracy and the government had been compelled to re upon the most reactionary forces, upon the military of the old regime. Democracy and the Government did not act uncompromisingly against the military, since antagonizing or weakening the military meant weakening the basis of their own power; hence the Government supinely allowed the preparations for a coup to proceed. A revolutionary Government would have answered the threat of Luttwitz to march upon Berlin by mobilizing the armed proletariat and by general arrests of reactionaries, by mass terror against the bourgeois Junker reaction; but the Socialist-bourgeois Government had disarmed the proletariat, while aggressive measures against the reaction would have meant an open break with the Right, and the collapse of the Government under pressure of Right and Left. At a meeting of the National Assembly on March 18, Socialist Chancellor Bauer said: “After mature deliberation the Government decided not to enter into a bloody struggle with the Kapp upstarts, and therefore determined to leave Berlin, thereby avoiding violence.” (Against the Communists there never was any thought of “avoiding violence”!) But that is miserable equivocation. The Government had at its disposal in Berlin alone 30,000 troops and 50,000 armed civilians, and about 300,000 in Government all Germany; yet the evaded a struggle with 10,000 counter-revolutionary troops. Why? Because the Government knew that its troops, reliable in crushing a Communist uprising, were completely unreliable as means of defense against a reactionary uprising. Moreover, an open military struggle would compel the Government to arm the proletariat, thereby developing the forces of proletarian revolution. The Government, accordingly, chose to retreat and compromise; never for a moment did the Socialist Government of Ebert, Noske and Bauer forget the menace of a proletarian revolution; concession to the Right rather than permit the revolutionary to proletariat conquer!

Democracy and the parliamentary regime, acclaimed as the final symbols of the Revolution and the means to Socialism, broke in pieces. Democracy? It was, in the persons of the Government, fleeing to Dresden in an automobile; and there issuing proclamations about law and order, right and the constitution at a moment when the issue was power against power and might against might. The Parliament, the National Assembly?

It was dispersed as chaff before the wind by the bayonets of the Luttwitz troops; the Reichstag, where the Assembly met, now as imposingly empty and impotent as democracy itself, was guarded by three soldiers, while children played upon its steps an appropriate memorial to Karl Kautsky.

The National Assembly dispersed, issued its defiance to the military coup, spoke of democracy and right, of law and the constitution, decided to in convene Stuttgart–and exercised scarcely any influence upon the march of events. The National Assembly, which approvingly observed the butchery of the workers on January 13, now, on March 13, was incapable of mustering either the moral or physical energy to resist counter-revolution.

The representatives of petty bourgeois democracy fulminated threats against the military coup, but the democracy itself was apathetic. Even where hostile, democracy had no means of its own for action against the counter-revolution. Moreover, for this democracy to act decisively against the counter-revolutionary troops meant precipitating a struggle within the military forces of the nation, to disrupt the power which maintained the ascendancy of democracy. The petty bourgeois democracy, accordingly, adopted a policy of “watchful waiting” and “neutrality,” which under the circumstances assisted the counter-revolution democracy did not defend itself against the Right, with whom it could merge; while preparing to maintain itself against the Left, with whom there could be neither compromise nor merger. It might be unpleasant for the military reaction to conquer, but a satisfactory agreement could be arranged.

This, then, was the consequence of the Socialism of the Social Democratic Party that, in affirming democracy as the means to Socialism, it developed means for the ascendancy of Junker Capitalism, thereby directly promoting the coming of military counter-revolution.

And after 15 months of murdering the proletariat and Socialism, the Government and the Social Democratic Party were compelled to call upon the proletariat to act against its own creation, the military counter-revolution.

2. Developments of the Crisis.

In choosing the alternative of a General Strike the Government and the Social-Democratic Party were fully aware of the fact that the Strike might develop beyond the limits imposed upon it as a strike in defense of democracy and the Government. But the Government was equally aware that it might depend upon the military in the event of the strike assuming revolutionary proportions, and, moreover, the Government, simultaneously with the call for a General Strike issued in the name of Ebert, Bauer, Noske, Muller and David (Noske afterwards denied subscribing to the call) prepared measures to prevent the General Strike becoming revolutionary. In the Ruhr District, for example, revolutionary and under a state of martial law, the Strike was consciously limited, and it did not become a General Strike until March 17, when the struggle was no longer against the military coup but against the Socialist-bourgeois Government.

In accepting the alternative of a General Strike the Government, moreover, simply “legalized” and accomplished fact, since the masses acted independently of the Government,

On Saturday March 13 the General Strike was proclaimed in Berlin by the trade unions, the Social Democratic Party and the Independent Socialist Party. All three proclamations agreed in fundamentals strike against the coup, in defense of democracy; the Independents juggled with revolutionary phrases in characteristic style, but proposed no definite revolutionary measures; while the trades unions spoke of the “legal” Government being menaced by the coup, of the danger of reaction being restored in state and shops, of the Republic being in danger. There was no clear call to revolutionary action, not even from the Communist Party which, on Saturday, declared against the General Strike on the assumption that the military coup and the Government were identical.

The response of the proletariat to the General Strike was immediate and complete; in Berlin, the struggle immediately and completely assumed the character of a proletarian struggle against the military-bourgeois reaction.

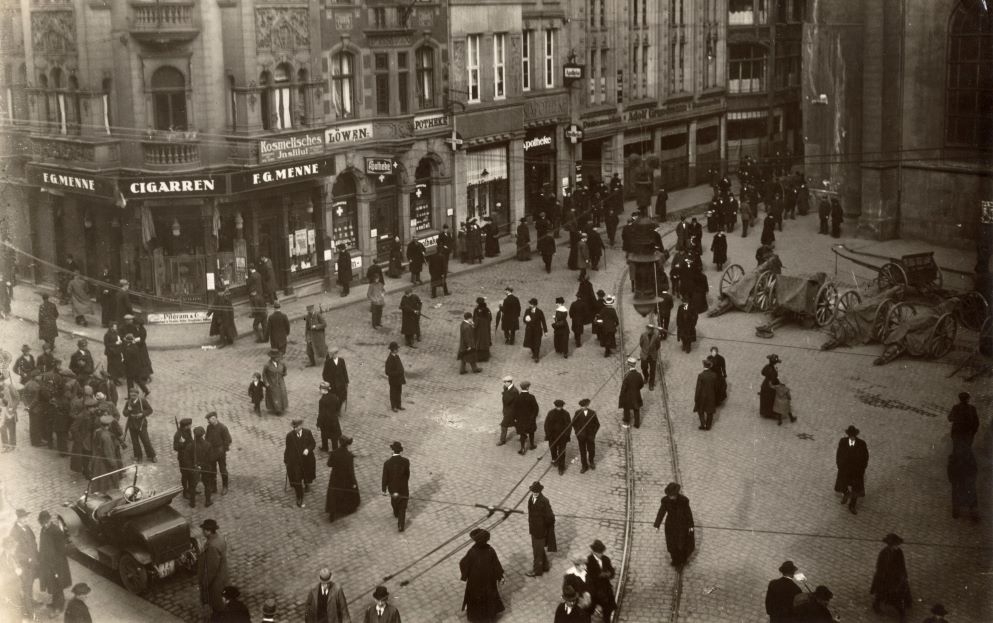

The situation in Berlin was most characteristic of the general situation in Germany. The collapse of the Government was complete; there was not a trace of this authority or its resistance…Herr Kapp occupied the Chancellery; while General von Luttwitz installed himself in the Ministry of war from whence Comrade Noske had issued orders of death against the Communist proletariat. This Government district, now a fortress of barbed wire entanglements, machine guns and artillery, opens on the Tiergarten where, fifteen months ago, Karl Liebknecht urged the proletariat to Revolution; while three streets beyond is the turgid canal into which the assassins of the Socialist Government cast the mutilated body of Rosa Luxemburg…The National Army either retired to its barracks or fraternized with the counter-revolutionary troops. The Noske Guards, insolently active in all the streets of Berlin the day before, now scurried to cover, and did not appear again until the struggle against the revolutionary masses started. The Einwohnerwehr (literally, Guards of the Inhabitants, civilian White Guards) issued a declaration of neutrality (neutrality under the circumstances meaning assistance to the counter-revolution) while emphasizing its readiness to march against “plunderers,” that is to say, against the proletariat; and it did march to action when the General Strike began to threaten “law and order,” and the struggle developed against the Government.

As against these open and masked forces of the counter-revolution, proletariat on General Strike was alone. It was clearly, emphatically the working class against all. The paralysis of industry, of most public activity, was complete; it was as if a giant mass of ice pressed down upon the city. The Kapp-Luttwitz Government was isolated; its troops occupied the streets, but the proletariat closed the factories, halted railway and street car traffic, and kept the city unlighted at night. The Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship issued innumerable proclamations about right and the constitution, bread and liberty, but the iron answer of the proletariat mocked it all; the Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship styled itself the “Government of labor,” but there was no labor; the Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship issued threats against the profiteers, but this did not worry the profiteers, while the General Strike did; the Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship issued a decree providing death for strikers and strike directors, but the General Strike implacably persisted. All Government authority, “legal” and “illegal”, was now a myth in comparison with the reality and the might of the General Strike.

The struggle of the proletariat in Berlin was, objectively, a revolutionary struggle. But, unfortunately, only in an objective sense. The proletariat was unarmed, while its representatives manifested neither revolutionary initiative nor political capacity. The fundamental task was to issue the call and develop measures for the arming of the proletariat; no such call was issued or measures adopted during the first four days of the General Strike the decisive period, during which the basis had to be laid for all subsequent action.

But elsewhere the revolutionary struggle flared up. Where the workers were armed they initiated struggle for power, and usurped power; in other places they disarmed the troops as a preliminary to the struggle for power. In city after city Soviet Republics were proclaimed; while in the Ruhr a giant revolutionary struggle loomed threateningly. Among these workers the military coup was a call to action, the opportunity to conquer power. It was the elemental action of the masses breaking loose, in spite of the dangers, in spite of the Party moderates and compromisers. These vital developments indicated that both the reaction and the Revolution had completely underestimated the German proletariat; the Reaction, its capacity to resist a military dictatorship; the Revolution, its will to engage in the struggle for power.

The menace of Bolshevism, which the Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship in its first proclamation had projected as a bogey, was now a real menace. To continue the struggle between the Government and the coup meant to prepare the conditions for the revolutionary conquest of power by the proletariat. What was necessary now was agreement and compromise, unity against the Revolution. The danger was very real. Hindenburg appealed to Kapp-Luttwitz to withdraw from Berlin, and to the Government for compromise and agreement. Now the strategy of the Socialist-bourgeois Government was apparent in avoiding the decisive military struggle against the coup, the opportunity was provided for agreement and unity against the Revolution. The opportunity was seized at the earliest moment.

It is a fact, in spite of denials, that the Government was negotiating with the Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship. On Wednesday these negotiations resulted in an agreement. On Monday the Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship had announced negotiations, and stated its conditions: “Elections to be held two months hence for the Reichstag and the Prussian Landtag; a new President to be elected, the former President to be requested to continue office until the elections.” This declaration was denied by the Government and the National Assembly; but the agreement was concluded two days later, practically on the Kapp-Luttwitz conditions. On Wednesday the Kapp-Luttwitz coup declared that, having accomplished its mission, the old Government agreeing (1) that elections should be held within two months and (2) election of the President to be by direct vote of the people, it would withdraw. This was not accomplishing the program of the coup, but it was a partial victory; and, moreover, the Kapp-Luttwitz troops withdrew from Berlin with all the honors of war, to the strains of martial music and assisted in their evacuation by the Government troops; carrying with them, moreover, an enormous mass of captured munitions. A proclamation characterized the agreement in this fashion: “After long negotiations between the representatives of the Government parties and representatives of both Right parties (which had recognized the Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship), especially between representatives Trimborn, Sudekum, Stressman and Hergt, the following compromise has been reached: The representatives of the majority parties will advocate elections to the National Assembly to take place not later than June; that the President be elected by the people, that the National Government will undergo a change in the near future; the carrying on of the business of Government in Berlin to be taken over by vice-Chancellor Schiffer.” At 12:15 Thursday morning, Schiffer issued a proclamation in the name of the Government, designating General Select as commander of the troops and calling for restoration of economic and political activity. (A joint proclamation by Schiffer and Hirsch (Social Democrat) in the name of the National and Prussian Governments declared it was false to accuse the National Army and the Security (Noske) troops of offering no resistance to the coup, and has this delicious bit: “It is not commonly known that on the night of Friday-Saturday (March 12-13) the troops stood at their posts ready to defend the Government; but, because of the difficult conditions of night fighting, they were, before the advance of the rebels, recalled to barracks”!)

Simultaneously with the conclusion of the compromise, the Government and the bourgeois parties issued the slogan: “Back to work!” The paralysis of the economic activity united with the menace of Bolshevism to compel a compromise. But the proletariat of Berlin rejected the call to end the strike, the trades unions and the Social Democratic Party being compelled to order the strike to proceed against the compromise.

The General Strike was now, in its impulse and in the mood of the masses, a Strike against the Government. But, in the conscious direction imparted to it by the trades union bureaucracy and S.D.P., the strike was against the compromise of the Government purposely or stupidly evading the problem, in that the compromise was not in a formal agreement but in the prevailing situation itself; the Government might repudiate the formal agreement but would inevitably be compelled to compromise, as actually did happen.

The compromise agreed upon by the Government and the military coup, the masses persisting in the General Strike, now in fact a Strike against the Government, these developments emphasized the inherent character of the crisis, as developing the conditions and providing the opportunity for the definite Communist struggle for power.

It was clear to all that the continuation of the General Strike was latent with the threat of proletarian revolution. On Thursday and Friday the citizens of Berlin acted as in mortal terror; the words Spartacus, Arbeiter, Unabhaengigen, were on all tongues and the basis of discussion in all crowds. At night, store and hotels were barred and people ordered off the streets: terror rampant in Berlin. The Government troops now occupied the entrenchments erected by the Kapp-Luttwitz troops and new entrenchments were erected. Riots were frequent, the Government troops using rifles and machine guns at the least pretext: in three days more persons were shot by the Government troops than in the five days of the Kapp-Luttwitz dictatorship. In the proletariat a new energy manifested itself, a developing consciousness of larger means and purposes. But the General Strike did not move to Revolution; nor was it the masses who were not ready, but the representatives of the masses…

Never were the limitations of the General Strike in itself more apparent than in Berlin. The Strike was complete; for eight days not factory nor a car was in motion. But in spite of all this, the strike broke and dispersed after unsatisfactory promises of concessions by the Government…

There are six aspects in the revolutionary conception of the General Strike:

1. A General Strike, if complete, must include the whole working class; but this temporary unity, while inspiring, is deceptive, since all groups in the working class are not in implacable opposition to Capitalism (officials, aristocracy of labor, trades union bureaucracy). The unity temporarily of fundamentally irreconcilable elements in a General Strike means that at a particular moment these elements will split apart and break the Strike. It is necessary, accordingly, to mobilize independently the potentially revolutionary forces, the industrial proletariat, the unskilled workers.

2. The limitations of the General Strike in itself are innumerable; unless it ceases being a strike it must break and disperse, since a General Strike presses more heavily on the proletariat than on the bourgeoisie–for example, the bourgeoisie can feed itself much more easily than the proletariat.

3. A revolutionary General Strike, accordingly, must cease being a Strike and become a revolution, mobilize itself for the seizure of political power.

4. The seizure of power implies breaking the military might of the bourgeois state; it is necessary, therefore, to arm the proletariat.

5. All that a General Strike can accomplish is to create temporary economic and political demoralization, making a breach in the old order through which the proletariat can break through for the conquest of power, its moral and physical energy, enthusiasm and mass consciousness being aroused by the General Strike.

6. A General Strike may become a revolution. But there must be adequate revolutionary leadership to formulate, at the start, the moral and physical measures which become the basis of action at the stage of the General Strike developing conditions of revolution.

None of these conditions were met. The fright of the bourgeois dissolved in smiles of satisfaction. The treachery of the moderates and the incapacity of the revolutionists prevented the General Strike becoming Revolution…

But should the Strike persist, danger would come: complete economic chaos and more revolutionary vigor. The Government, accordingly, again compromised; it repudiated the Schiffer “Intermediate” Government and established itself in Berlin. The trades union bureaucracy met the Government in conference; a compromise was agreed upon (to be repudiated by the Government in two days); and two hours after this conference Legien and other reactionary union officials issued an order to end the General Strike (the conference ended at 5 o’clock Saturday morning, and at 7:05 the proclamation calling off the Strike was issued). The same day the Independent Socialist Party (Speaking through Crispien in “Freiheit”) also urged ending the General Strike.

The situation on Saturday, may be summarized:

1. The trades union bureaucracy, moderate, treacherous, and itself as much in fear of a revolution as the Government, broke the Central Strike. This bureaucracy, petty bourgeois to the yearned for “tranquility.” The conditions of the unions were moderate, vague and general, capable of easy “interpretation” and repudiation: immediate disarmament and punishment of participants in the military coup; clearing the Government of reactionaries; new laws for equality of workers and officials (!); immediate socialization of industries ripe for socialization (now urged by the moderates for more than a year); drastic action against profiteers, if necessary by expropriation. Two interesting conditions were: 1) “Representatives of the Government parties will defend the right of the workers’ organizations to participate in the reconstruction of the Government, the unions to have a decisive influence. 2) Dissolution of all reactionary military formations which have acted against the constitution, and their replacement by reliable Republicans, especially from workers, employees and officials without neglecting any profession.” Magnificent evasions of the problem of power! As if even these moderate conditions could be secured by compromise agreements and paper concessions, and not by means of conquest of power!

2. The Independent Socialist Party acquiesced in ending the General Strike while calling upon the Government to arm the proletariat–as if the Government would cut its own throat. It issued other demands which were either miserable compromises or else incapable of accomplishment without the conquest of power. But, most characteristic and miserable of all, the Independent Socialist Party issued the call for a “Socialist Government” the exclusion of the bourgeois parties from the Cabinet, which was now to consist of Social Democrats, Independents and representatives of the trades unions. This was the final compromise of compromises coalition with the assassins of the proletariat and the Revolution as a means of expressing the Revolution and the proletariat.

3. The Left Wing Independents and the Communist Party repudiated the call to end the General Strike. Continue the General Strike for what? Against the Government’s compromise with Luttwitz-Kapp?

But that compromise was in the objective facts of the situation, not in any formal agreement. Against the Government? But that meant a revolutionary struggle for power. Neither the Communist Party nor the Left Independents, however, were prepared to engage in this struggle: the Left Independents because of their affiliation with the Independent Socialist Party; the Communist Party because it affirmed that the proletariat was not ready for the seizure of power. There was issued neither a definite call to revolutionary action nor a definite revolutionary program. Moreover, the disastrous character of the situation was emphasized by both the Left Independents and the Communist Party acquiescing in the Independent Socialist Party proposal for a “Socialist Government.” The Left Independents accepted the proposal enthusiastically, prepared to participate in such a Government; the Communist Party, through its Reichs-Zentrale, declared it would wage only “loyal opposition” to such a Government a declaration which perfectly satisfied the Independents and which they interpreted as approval. This was the final and worst mistake of a series of mistakes: it completely smashed any prospects of revolutionary action developing out of the General Strike.

Betrayed by the S.D.P. and the trades union bureaucracy, missing the urge of revolutionary direction and inspiration, the General Strike was on the verge of breaking. The non-proletarian elements in the working class immediately acquiesced in the order to end the strike; but large masses of the proletariat rejected the order. On Saturday and Sunday, while the representatives of the masses hesitated and compromised, the masses were again in a mood for action. The call for Soviets might have met response; but while the Communist Party issued this call, the Left Independents issued the call for elections of revolutionary Betriebs-Rate (Factory Councils, economic Soviets); and the C.P. acquiesced in the call. The Communist Party, as represented in its Reich-Zentrale, met the retribution of its incapacity: it might now issue the necessary revolutionary slogans, but these would not meet response, since comrades are the Communist Party had developed neither the moral energy nor the revolutionary enthusiasm of the masses; while these revolutionary slogans were now vitiated by the Zentrale’s compromises with the Independents. Undoubtedly it was too late to initiate now an immediate and successful struggle for seizure of power; but the Communist Party owed it to itself and the Revolution to come clean of compromise, to formulate measures and action calculated to develop moral reserves for action in the days to come…

On Monday the representatives of the revolutionary Betriebs-Rate elected the previous day met in the General Assembly. Large numbers of workers had returned to work; but large masses were still on strike, the Betriebs-Rate Assembly itself presenting 500,000 workers. The Assembly, dominated by the Independents, decided to “interrupt” the General Strike, the Communists urging continuing the Strike, but the Independents carried the day. The “interruption” of a General Strike as a revolutionary tactic depends upon circumstances; unless it is adopted at a moment when the Strike is at the crest of its power, but conditions make it impossible to conquer, hence it becomes necessary to secure a period for new preparations, “interrupting” a strike is simply a cover for defeat. Under the prevailing condition, this maneuver was characteristic of the Independents.

The Communist Party opposed this “interruption” of the General Strike, and rightly. Even now, considering the general situation and particularly the intense revolutionary struggle in the Ruhr, continuation of the Strike two or three days more would have disorganized Capitalism and the state, might have developed a struggle, and encouraged the Ruhr proletariat.

But the General Strike was “interrupted:” And from the Ruhr proletariat, waging a magnificent struggle and menaced on all fronts. came the searing cry of “Treason!” hurled at the representatives proletariat of Berlin.

Emulating the Bolsheviks who changed the name of their party in 1918 to the Communist Party, there were up to a dozen papers in the US named ‘The Communist’ in the splintered landscape of the US Left as it responded to World War One and the Russian Revolution. This ‘The Communist’ began in September 1919 combining Louis Fraina’s New York-based ‘Revolutionary Age’ with the Detroit-Chicago based ‘The Communist’ edited by future Proletarian Party leader Dennis Batt. The new ‘The Communist’ became the official organ of the first Communist Party of America with Louis Fraina placed as editor. The publication was forced underground in the post-War reaction and its editorial offices moved from Chicago to New York City. In May, 1920 CE Ruthenberg became editor before splitting briefly to edit his own ‘The Communist’. This ‘The Communist’ ended in the spring of 1921 at the time of the formation of a new unified CPA and a new ‘The Communist’, again with Ruthenberg as editor.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thecommunist/thecommunist3/v2n07-jul-01-1920.pdf