Philip Sterling recounts the history of vaudeville, once a preeminently popular form of entertainment, and the crisis technological and cultural changes along with the Great Depression, created. He asks, is it worth saving and answers yes, but.

‘Vaudeville Fights the Death Sentence’ by Philip Sterling from New Theatre. Vol. 3 No. 2. February, 1936.

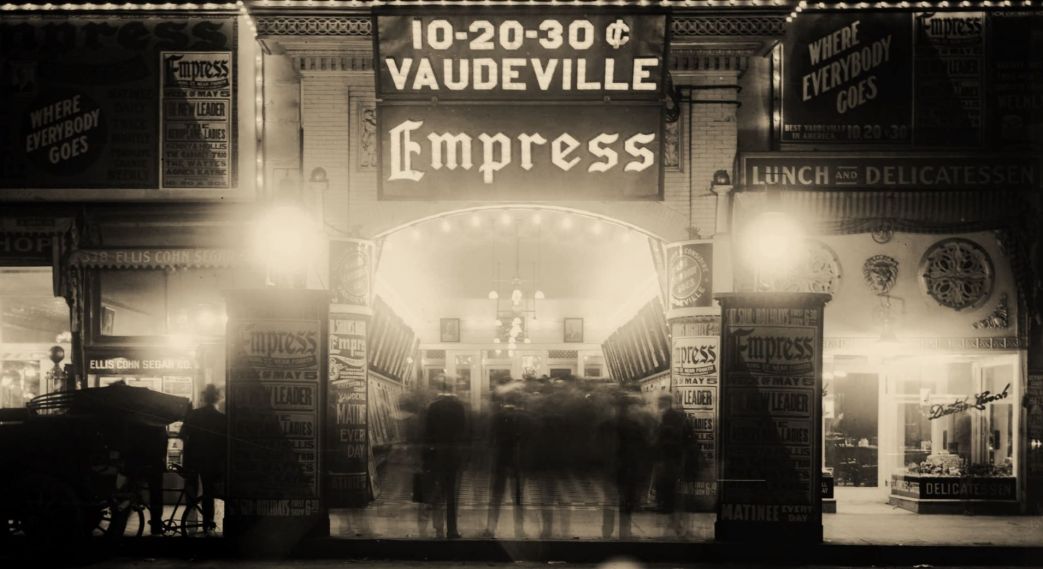

American theatre audiences, long accustomed to taking what is handed to them have apparently paid scant attention to the rapid disappearance of vaudeville from the popular stage during the past six years. This may have been due to the fact that during this period there was a decided trend away from the box-office queues toward the breadlines.

In any event, the causes of variety’s fall to its current sad estate are close at hand. They may be traced from Longacre Square directly down Broadway and up Pine Street to the Chase National Bank and a few other institutions whose financial control of the movie industry have given the money-men powers of life and death over America’s entertainment. With the advent of the talkies, radio and the depression, the money-men decreed death for vaudeville.

The simple retrenchment policies of all business enterprises during the depth of the depression is not enough to explain the forcible ejection of vaudeville from the theatre, because in the theatre business the retrenchment policy wasn’t simple. It entailed a complete rebuilding of the financial foundations and the administrative and distributive superstructure of the movie world. And as the movie world went, so went vaudeville for the cross country network of theatres which makes it feasible and profitable for actors to work continuously by traveling short distances was largely in the hands of the financiers who by 1931 had taken complete control of the movie industry.

In the process of rationalizing movie production itself, there developed a now perfected plan of making full-length “program” pictures which had no particular merit but which helped fill out an entertainment bill from which vaudeville had been eliminated. This was so because the monopoly theatre chains, RKO, Loew’s, etc., having fired the body of vaudeville actors virtually en masse found it necessary to provide an accept able substitute attraction at once, particularly in years when it was hard to lure a single dime from the pockets of Americans for any non-essential. Following the old show-world dictum, the producers immediately decided to give the suckers more for their money without worrying too much about quality. This move stepped up production, too, at a time. when the movie industry was on its wobbliest legs in history. The question of whether independent theatre managers or the customers would like it wasn’t a consideration. The deadly block-booking system makes exhibitors, like their patrons, take what they get. Thus grew up the somewhat tedious institution known as the double feature bill which generally gives the theatre audiences two lousy movies for the price of one half-decent one.

The double feature, and radio, which offers everything in vaudeville except personal contact, are still two of vaudeville’s chief bugaboos.

Now, after six years in the deathhouse, vaudeville is beginning to put up a fight. There is a chance that the fight may be a winning one because it is being conducted by an economic organization of the vaudeville artists themselves. There are about 43,000 members in the American Federation of Actors. the members of the American Newspaper Guild, they have begun to put behind them the false traditions of their profession’s glamour which in former years isolated them from other wage-earners. They are members of the American Federation of Labor, proud of it, and damn sorry they didn’t think of it before. The reason for that, however, lies in the history of company unionism as embodied in the National Variety Artists. But that’s part of another story.

The pertinent thing is that the American Federation of Actors has for more than a year been conducting an energetic “Save Vaudeville” campaign. Logically, this raises the questions: Is vaudeville worth saving and how can it be saved?

Many unthinking though well-meaning patrons of the dramatic arts may immediately reply:

“Vaudeville is a cheap, outmoded stage form that is dying not only because of external economic and social influences but because it has always been essentially banal, innocuous, and boring.” In this reply there may be a half-grain of truth. Speaking strictly for himself, however, the writer believes that vaudeville is worth saving and that it has not always had those essential faults named above. Vaudeville is a valuable theatre form, valuable, as is the rest of the theatre, not simply as a highly effective social instrument but as an excellent means for revitalizing the folk-flavor of the stage.

Its main faults are not inherent ones. They lie in the current content of vaudeville which has been gradually squeezed dry of all vitality by the deadly hand of monopoly control in the same manner that the cinema, the legitimate stage and radio have been devitalized by the same agencies.

The encyclopedias credit one Olivier Basselin, a fuller of Normandy as being the father of vaudeville. The word itself is supposedly a corruption of les Vaux de Vire, the valleys of Vire, where Basselin worked and wrote his barbed satirical drinking songs directed at the land-holding clergy, the French feudal court, the aristocrats and the landlords. But whether the encyclopedic information is accurate or not, vaudeville, since those fifteenth century days, has devoted its lilting songs, its light-footed, light-hearted dancing, its glib tongue and its nimble. hands to comment, criticism and burlesque of the life of the common people.

Until the twentieth century, the formal drama, the legitimate stage, were even further beyond the reach of the people and removed from their interests than is the case today. Vaudeville, in one form or another with its pithy turns, its intimate contact between audience and performers, has, as a result, existed in every modern country.

The evolution of vaudeville in the United States, however, was different. Like the rest of American life, its various stages of development were rapidly and violently telescoped. When vaudeville began to make its first consistent appearances in this country some seventy-five years ago, it was quickly was quickly seized upon for exploitation by the Barnums and other “great” showmen of the period.

In other countries vaudeville had developed as a folk-expression which drew its material to an extent at least, from the problems and the everyday lives of the people, of its audiences. In this country it evolved from the raucous, obscene side-show exhibitions which were held out by the showmen as come-ons for the stuffed whales, the two-headed calves, and the wax work figures on the inside of the tent.

When Barnum and his ilk had cleaned up in the hinterland, they headed east again and opened up pretentious theatres. Their attractions were modified and refined until Jenny Lind replaced Jo-Jo, the dog-faced boy, because presentation of Jenny Lind could command higher prices. Here was the beginning of the entertainment and show business monopoly that came to full bloom with the perfection of the movies. And once the monopoly got under way, the chances for an American vaudeville stage with a genuine folk vitality went permanently aglimmering.

It should be pointed out, however, that even despite the petty censorships imposed on vaudeville from within and from without the most popular and successful acts have been those with some slight amount of social content. The examples of Clark and McCullough and Gallagher and Shean are typical but it would be difficult to multiply them in the history of the vaudeville stage. Another indication of vaudeville’s inherent vitality-denied the right to make fun of social and political happenings, it has never ceased to make fun of itself.

There is no type of act in vaudeville that has not been burlesqued by some other act.

Up to this point the record of American vaudeville is not particularly bright. Why, then, is it worth saving?

The answer is this: Bad vaudeville is not worth saving but there has been and can be such a thing as good vaudeville. Good vaudeville combines individual virtuosity in anything from juggling to doing bits of Shakespeare and the live folk-spirit and dash which makes for creative entertainment. The flexibility and mobility of vaudeville make it an appealing form for social comment, and there is no contradiction between this and entertainment. The more vital the social content the social content the more entertaining vaudeville will be.

The theory is that people seek entertainment to relax, to forget their troubles. But such relaxation and forgetfulness are emotionally and almost physically unsatisfactory unless they evoke a response or an emotion of which the individuals in the audience are aware after they leave the theatre.

Nobody remembers the infinite variations of “Who was that lady I saw you with last night?” But when you hear the story about the man who stormed into an office and demanded a job, you have subject matter for humor which lies close to the heart of virtually any audience. The man in this case was rebuked by the prospective employer. The rest of the story goes like this:

Employer: That’s no way to ask for a job. You’ve got to be polite. Come back in an hour and try it again.

Applicant: (Returning an hour later with meek countenance and hat in hand) I beg your pardon, sir. But you recall that you were kind enough to tell me I could return here and make application for employment. Is that privilege still open to me?

Employer: Yes. And this certainly is an improvement on your first appearance.

Applicant: Well, you can go to hell. I’ve got a job.

The audience to which the writer heard this yarn told was justly enthusiastic in its response. How much more deeply this moved them than a stale pun with a sexy innuendo was obvious.

The simple conclusion of all this, and one with which important vaudeville figures agree, is that if vaudeville is to be revived and preserved it must have new material and new theatres free from the paralyzing grip of commercial monopoly.

How new theatres and new material are to be acquired is, of course, no simple problem. A discussion of the subject with Ralph Whitehead, executive secretary of the American Federation of Actors, convinces this writer that the fate of vaudeville lies in the hands of the members of the profession. Organization on an adequate scale and close collaboration with the rest of the labor movement offer a real possibility of rescuing and raising vaudeville to higher cuing and raising vaudeville to higher levels than it has ever known.

It is possible to envision the enlargement of the union’s booking office, the establishment of a string of vaudeville theatres from coast to coast closely allied to the union or even owned outright by the actors themselves and thus free from monopoly censorship. Even better, he pictures solid coast to coast year-round bookings for vaudeville shows under the sponsorship of trade unions and other labor groups. After all, here is where vaudeville’s real strength lies. It doesn’t need a theatre. It can spring to life and do its stuff in any hall or out of doors.

Another possibility is that hundreds of dark theatres could be opened by the use of Federal subsidies and that official stiff-necked censorship could be avoided by actor and audience control of the theatres. Such a program, with its admit- ted difficulties, could be achieved by effective organization and the combined mass pressure of the actors and the rest of the labor movement.

Mr. Whitehead, who may be regarded as an official spokesman for the vaudeville artists, agrees that the medium needs new material, but just how new and how sharply changed, he isn’t sure. He believes that a process of audience-education would be necessary. There is no doubt, however, that a process of act- or-education would be an even more pressing need.

Vaudeville actors who have grown up in the stultified atmosphere of mother-in-law jokes, mammy songs and sexy double entendre will have to begin, as did Gallagher and Shean, Will Rogers, Dr. Rockwell, Ed Wynn and Eddie Cantor, to look to the newspapers and to current events for the substance of their acts, only they will have to look deeper into the headlines than their predecessors. They will also have to look into the headlines with greater sympathy for the interests and needs of the wage-earners and lower middle class who constitute the bulk of their audiences.

At least one vaudevillian has already shown himself to be aware of this need–one Steve Evans whose fascinating and intelligently conceived impersonations this writer saw in a typical New York neighborhood theatre. It may be accident that Mr. Evans’ portrayal of John D. Rockefeller playing golf on his ninety-sixth birthday is so devastatingly satirical but the enthusiasm of the audience’s response should tell him and other variety artists that here is a track worth pursuing. Most moving of all his bits is his characterization of a Polish steel worker getting drunk on pay-day. Those who are redder than the rose may say that the bit is a libel on the working class. Evans acting skill in portraying a drunkard, his oral deftness in portraying the vagaries of a Slavic tongue wrestling with an unfamiliar tongue, are not the point, however. What makes his Polish bit vital vaudeville art is the manner in which he conveys the motivations of the character he portrays. You feel that here is a guy who’s got a right to get drunk. Your sympathies are entirely with him. You want to climb over the footlights, make the big, shambling good-natured fool put his money back in his pocket and take him home to his wife. But when he suddenly discovers that he hasn’t the “pflent-yeh moonyeh” of which he has been boasting, you realize that he has been robbed not merely by a pickpocket who preys on drunks, but by the life he lives. When he goes staggering off stage with a crying-jag about his wife and the six kids waiting for him at home, you are moved not by the maudlin sentimentality so common to vaudeville but by a deeper and more powerful emotion that remains in your consciousness long after you’ve left the theatre. Maybe Mr. Evans didn’t think all of this out in advance but it’s all there and it’s all vaudeville.

The audience-education postulated by Mr. Whitehead doesn’t seem so essential Certainly no advance build-up went into the wild acclaim and sweeping popularity which met Waiting for Lefty. (Seems you can’t write about the stage without mentioning that play.) By the same token any act which could do as much for the vaudeville stage would need no process of education to make it acceptable to audiences.

Another possibility grows from all these considerations. Should the idea of a self-sustaining, mass-supported labor vaudeville stage be quickly realized, and it could be, the masses of America would have a lever for freeing the movies from the grip of the Wall Street-Hollywood monopoly. With an established audience and a reliable source of financial support which would make it possible to tour vaudeville from coast to coast at a profit, the surpluses could be diverted to the production, distribution and exhibition of labor films which are now impossible because of a lack of financial resources.

One additional proof of the argument that vaudeville needs new material and that new material will interest large audiences may be offered. The experiments of the new theatre movements with vaudeville forms in New York, Chicago, San Francisco and other cities have been highly successful. Like its other efforts, the vaudeville of the new theatre movement has attracted not only audiences from the limited field of the organized labor movement but from the middle class groups as well who are perhaps the most hungry for good theatre. It is from both of these groups that vaudeville has drawn the vast bulk of its past audiences and from these that vaudeville must rebuild its support.

Vaudeville isn’t dead by a long shot, but from now on its life depends on what it can give to labor and the middle class and what these groups are prepared to give it. On one last point the body of vaudeville artists themselves should be reassured. The actors must disregard mother-in-law jokes and mammy songs for acts that mean something to the great mass of the American people. If they do so, they will have only passing difficulties in finding paying audiences throughout the country that won’t sit on their hands.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n02-feb-1936-New-Theatre.pdf