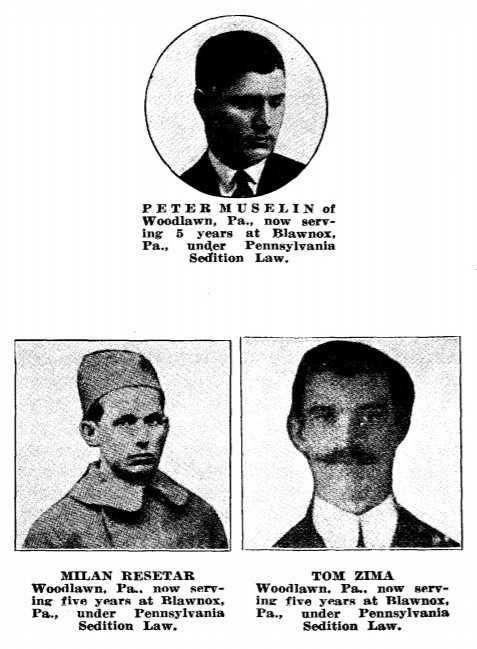

Croat-American baker and Communist Milan Resetar was living in Ambridge, Pennsylvania when he was arrested in 1927 with two other comrades, the Woodlawn Defendants, and charged with sedition for having Party literature. The three were sentenced to five years in prison. Unbowed, Resetar ran for State Senate while at the Allegheny County Workhouse. There his health failed, tuberculosis, and he was denied treatment which resulted in his death shortly before his release date. Milan Resetar, Presente!

‘Death in an American Dungeon’ by Paul Peters from Labor Defender. Vol. 8 No. 1. January, 1932.

EVEN after they had stowed away Milan Resetar in prison for five years, the hate of the steel lords pursued him. It hovered over his dark little cell at Blawnox. It pressed down on him as he labored, sick and broken, in the prison workshop.

In the end it killed him.

For wasn’t Milan Resetar a “dangerous criminal”? Hadn’t he read Lenin in the realm of Jones and Laughlin, steel kaisers of Woodlawn, Aliquippa, and Pittsburgh? And hadn’t the courts decreed that a man who read Lenin in the land of the steel lords was guilty of “sedition,” fit only to be buried away in a thick-walled dungeon with bootleggers and murderers?

Milan Resetar entered prison a robust man. Then the foul dungeon air began to fester in his lungs. The deadening prison diet began to gnaw at his bowels. He was wracked with pain. He wasted away.

“You are bluffing,” sneered the prison doctor. “You are a malingerer. You pretend to be sick because you do not want to work. You think if you act sick, I will ask for your parole.”

To his chief, this care-taker of slaves in the dungeons of the steel kings reported that “Resetar was a peculiar man mentally–not insane by any means, but peculiar and eccentric.” (Hadn’t he read Lenin? Hadn’t he had faith in the triumph of the workers?) Otherwise, the doctor added, “I found him to be without physical defects.”

“Dr. Mitchell did not like Resetar, or Tom Zima, or me either,” writes Peter Muselin, one of these three friends, raided, arrested, and sentenced together. “He does not like anyone who is here for sedition.”

When he could hardly stand any longer they sent Milan Resetar to the prison infirmary. “Palpitation of the heart,” they called his ailment. Five days later they thrust him out again, back to the grim prison workshop and the bleak prison cell. They said he was “improved.”

And then the old doctor went off on a vacation and a new doctor took his place. He saw this sick man staggering in anguish. The sweat of death was already on his face. A week after he had been dismissed from the infirmary as healed, they carried him to a bed again.

They found his lungs eaten up by tuberculosis, his heart enveloped in a pus sac.

And now they saw that Milan Resetar–Resetar the “malingerer,” Resetar, the “actor” and bluffer”–now they saw that he was dying.

The International Labor Defense tried to get him out of prison, into a hospital. They wrote letters, sent telegrams, made protests. They appealed to the judge, to parole board members, to the prison superintendent, to Governor Gifford Pinchot.

Some flatly refused to act; some said they could not; some passed the buck; the governor never replied.

Within a month Milan Resetar was dead.

Then came alibis, excuses. “I gave Resetar every possible medical care and attention,” chants the doctor in a pious prison report. “Nothing more could have been done for him in an outside hospital. He came to his death by natural causes.”

To the last Milan Resetar stood by his revolutionary faith. Even with death in his veins, he refused to yield by a tittle. “Before his death we offered to furnish him with the benefit of clergy,” reads the prison report with an air of rebuffed magnanimity, “but he refused this service, although he had been raised in the Catholic church.”

They buried Milan Resetar at a mass funeral.

Instead of the hypocritical cant of the preachers, fellow workers spoke of his belief in the fight of the workers, of his steady faith in their ultimate victory. Something of this faith rose up and pervaded the crowd of mourning men-as it will spread and strengthen workers everywhere: to stand more firmly together till the steel lords are overthrown and the prison walls are broken down.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1932/v08n01-jan-1932-LD.pdf