An inside look at an important strike in bringing forth industrial unionism into the labor movement was that of the Little Falls, New York textile workers in 1912-13. Robert Bakeman was a leading member of the Socialist Party in nearby Schenectady, where the Party held the mayorship, and was one of the first activists on the scene in helping what was at first an unorganized walk out of largely immigrant workers.

‘Little Falls: A Capitalist City Stripped of its Veneer’ by Robert A. Bakeman from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 6. February 8, 1913.

When one has thrown his whole being into a description of events that really seem to justify the free use of superlatives, he is rather taken aback when he is calmly asked, “Well, what more can you expect of the capitalist system?”

It takes a finished philosopher to hold continually in mind the doctrine that a given institution is but the reflex of the prevailing method of production, when one has such memories to combat as have we who were in the strike at Little Falls.

But the calm man is right and much as we should hate to have everybody cured all at once of that soul-satisfying inconsistency that permits a man to say in one breath that we are all caught in the system and in the next berate the individual capitalist, we must start out with the idea that Little Falls is an industrial city under the capitalist system and that the difference between her and other industrial cities is that she has violated the eleventh commandment and has been “found out.” Making slight allowances for the personal equation, it seems perfectly reasonable to think that with a similar strike in any other industrial center of the United States, Little Falls would be practically duplicated. The great fact that this country faces to-day is that the time is rapidly approaching when the employer of labor will not be able to grant the demands of the two million skilled laborers for shorter hours and more pay and charge the bill to the fifteen million unskilled and unorganized workers. A movement of the workers from the bottom up has started, a movement bigger than any labor organization. It is to her millions of unskilled workers that the nation must look, for the centre of the stage is theirs. No movement of the future can ignore them.

Little Falls is of importance only because it is one more of the signs that the giant who has slept so long is really awaking and because there is revealed the cancerous growth sapping away the vitality not only of Poles and Italians and Slavs but of a whole community–yes, of a nation.

Little Falls is a water-power village that has attracted half a dozen industries to its river-banks. Chief of these are two large woolen mills that knit sweaters and are apparently competitiors. There are about 2,500 men and women employed in the two mills. Up to October the wages were from five to ten dollars a week, with an average of about seven. But always in computing the wages of the workers we must bear in mind that a good many of them do piece work and that there are times during the year when there is very little work for them to do. The yearly income of a given worker, which is really the only fair basis of reckoning, is almost impossible to get. A feature of the work was brought out before the state investigating committee that had not been noted before, showing up one of the vicious characteristics of “piece-work.” It appeared that be- fore Oct. 1 in order to make six or seven dollars a week many of the girls had worked eleven, twelve and thirteen hours a day with only a few moments for lunch. In the little while between the enforcing of the 54-hour law for women and the beginning of the strike, men had been put at night work in the mills, and since there was no law to protect them, they were made to work twelve and thirteen hours a night, with no time off for lunch. It is fair to say here that the American-born or English-speaking girls were paid considerably higher wages than the others. And the whole strike revolves about the foreign-speaking peoples: the Poles, Italians, Austrians and Slavs, of whom there must be from 1,500 to 1,800 in the mills.

The fifty-four hour law was a sop thrown to labor. The politicians thought no more of it. And to the manufacturers it seemed a mere matter of adjustment in the bookkeeping department. Since the legislature took off ten per cent of the hours of labor, was it not the proper thing for the manufacturers to take ten per cent. off the wages? Where a girl had been making $6 they reduced her pay envelope to $5.40. The man who had been making $7 was reduced to $6.30. That was all there was to it. And if the manager of the mills as he handed over a check for a thousand for some pet philanthropy did think of the effect of that cut upon his employees, he may have very righteously comforted himself with the thought that the Legislature was to blame. For wasn’t he perfectly willing that they should work sixty hours or even sixty-five, and get paid for it, too?

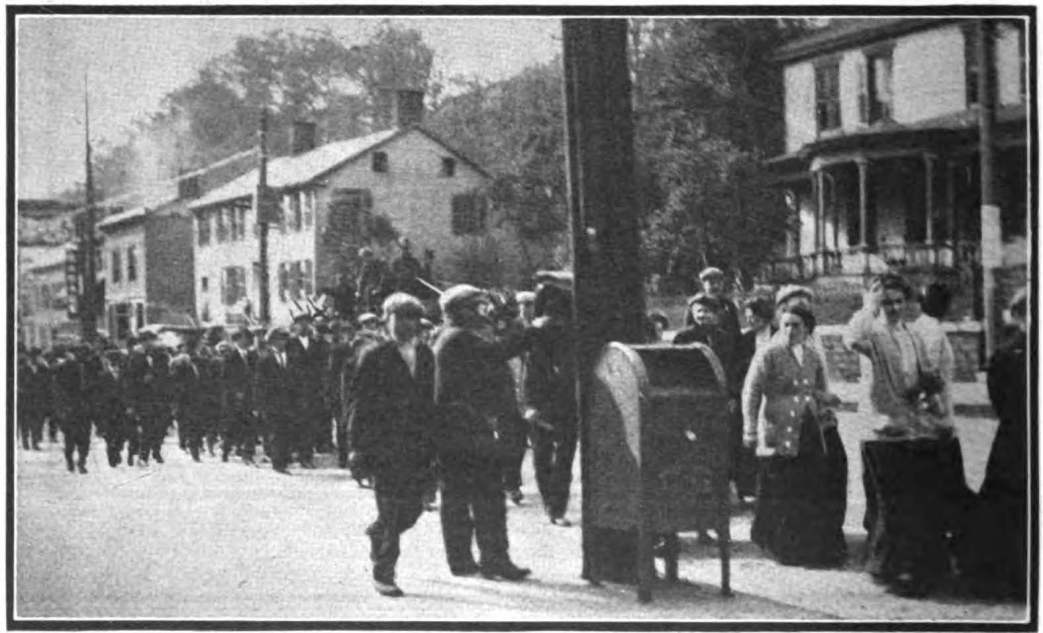

But the backs that had always adjusted themselves to receive any burden that was handed down to them, suddenly stiffened up. The “last straw” had been added. Perfectly spontaneously, as far as I can learn, without the slightest suggestion from outside their own ranks, nearly a hundred refused to go back to their work unless their pay was restored. Whether it was a knowledge through their own people of the Lawrence Strike or whether the workers felt that human nature could bear no more may be a question, but certainly the strike was spontaneous.

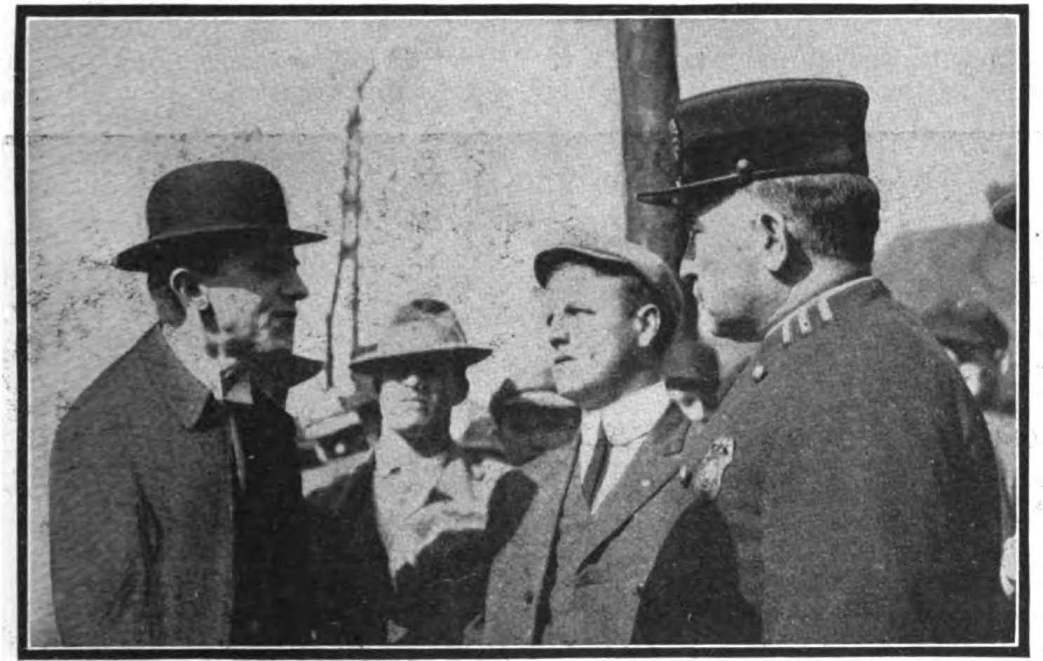

A classical pronouncement of the Little Falls strike came from the pen of the Chief of Police: “We have a foreign element on our hands. We have always kept them in subjection and we intend to in the future. We will allow no outsiders to ‘butt in’.”

I haven’t the slightest question that this represented Chief Long’s honest conviction and from our subsequent experience with him we feel sure that if it had not been for the coming in of outsiders he would have strangled the strike at its birth. Some time–perhaps Little Falls isn’t enough–American municipalities will awaken to the tremendous power lodged in their police authorities. Some time they may realize that there are other questions of importance in regard to a candidate for the police force besides his weight and height.

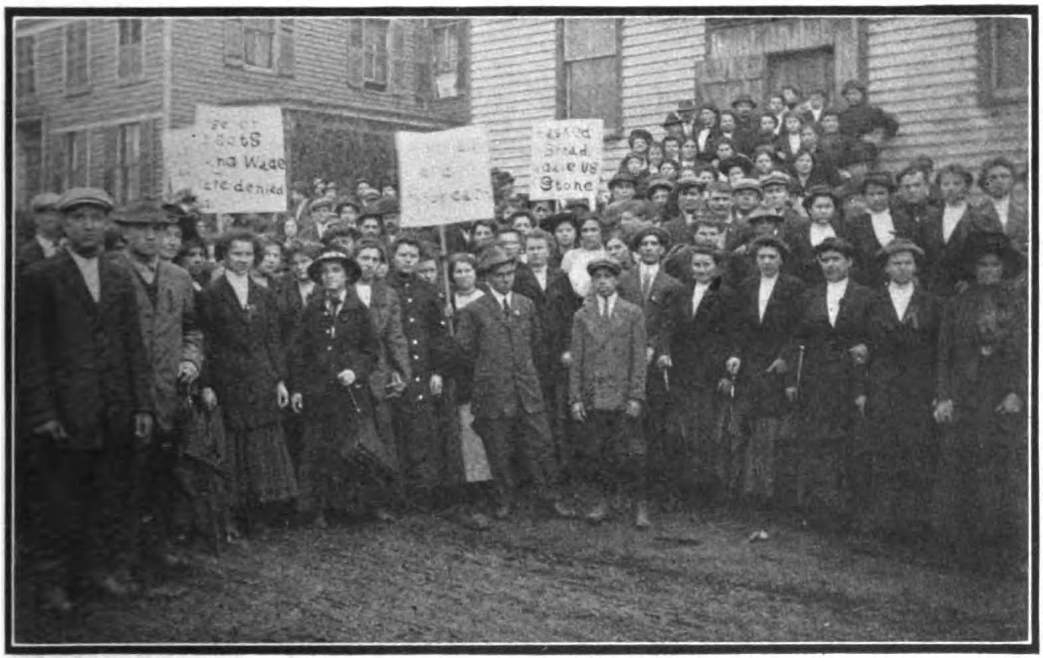

Here there were 1,500 people of four different nationalities, without a knowledge of the English language, unacquainted with our customs and our tangle of laws, without any organization–these at the mercy of a man trained in the subtleties of our business piracy and whose job depended entirely upon the extent to which he was able to exploit them. And he declared he would allow no outsiders to help them. But the outsides came just the same. A few of us went first to see if our knowledge of the English language would be a help, and then to urge the workers to get into some organization where their energy would be conserved. We found one man talking in Polish, urging the strikers to join the A.F. of L. Another followed him in Italian pleading the cause of the I.W.W. We picked up five sticks from the gutter and broke one, and then put the five together and showed that they could not be broken. The people seemed to understand and nothing more was said about either organization for more than a week, when the people themselves demanded that an I.W.W. local be formed. I want to repeat that an honest attempt was made to keep the strikers from becoming confused by the injection of the labor union issue until after the strike was won.

With our coming began the process of stripping the veneer from Little Falls. It had the same kind that every city has. From the heights the usual number of church-spires could be seen. I guess there was a Y.M.C.A. there, too, and the Fortnightly Club was composed of fashionable women who studied civics and hired a nurse to go through the miserable tenement houses owned by some of their husbands. The second day of the strike some of these club women were holding out boxes to the striking mill workers, asking money for the hospital Tag Day.

To be perfectly fair with them we must suggest our conviction that Little Falls didn’t really know the extent of its veneer. The women thought they were interested in the tenement house proposition until they were shown that the worst ones belonged to their own families. The minister of a large church in the city really thought that he would be true to his friend Mayor Lunn from Schenectady until he heard that the Socialist pastor-mayor was down in the city jail, arrested for having to do with a strike that affected some of his wealthy parishioners. The woman that refused to let Helen Schloss, the district nurse who joined the strikers, room longer with her because her friends were criticizing her, hadn’t realized before that she could ever do a thing like that. The business men who came to us, like Nicodemus, by night and told us we were right but that we must not mention their names, no doubt hated to have to feel they were cowards. The men who saw girls and women beaten and realized that this was fundamentally a strike of mothers and daughters to maintain a wage that would keep them from falling below the level of decency, undoubtedly blushed as they heard the clanking of the chains of social ostracism and economic pressure that held them in bondage. But it would be unfair not to make note of the fact that there were a few, and perhaps more of whom we did not hear, who broke through these chains and showed the red blood of manhood.

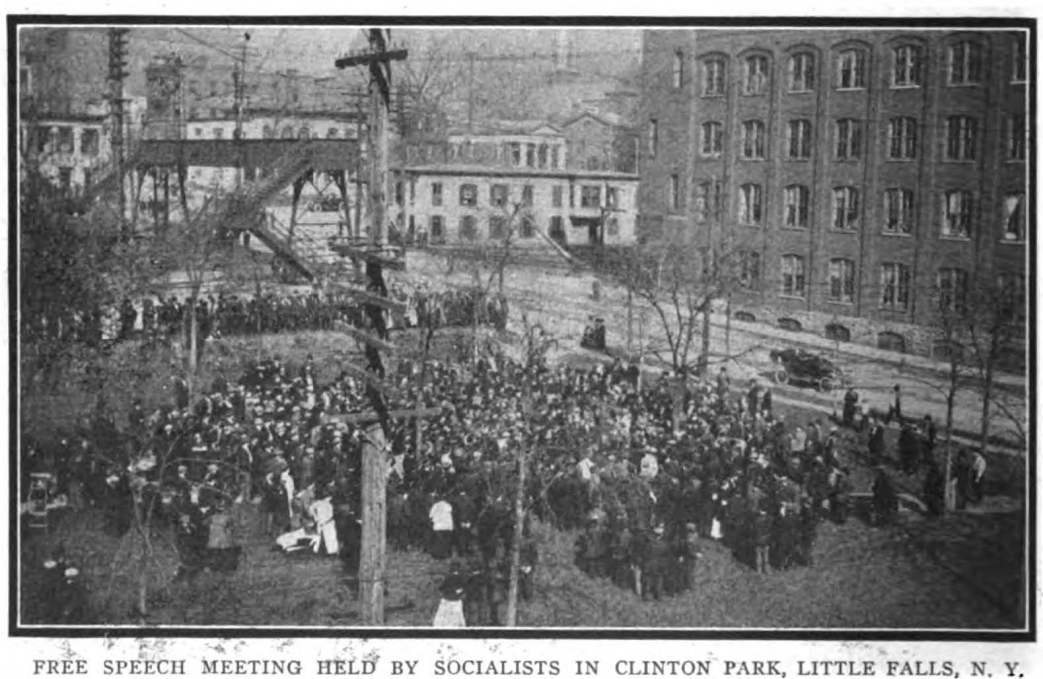

To one who has followed at close range the situation at Little Falls from the beginning it has been increasingly evident that the purpose of the authorities was to crush the life out of the strike before it was really born by ridicule and threats. Failing in this, they gave a mild hint of the limits to which they would go if the strike reached full strength; they would beat it to a jelly with brute force. They didn’t want to use the last method unless they had to, but they were prepared to if it were necessary. They didn’t care about anything but the strike. They wouldn’t have cared if the Mayor of Schenectady had barked his head off in Clinton Park; they wouldn’t have objected seriously if a hundred Socialists had addressed audiences every day —about anything but the strike. Those simple-minded men had not the slightest intention of handing body-blows to the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence and the Bible. It wasn’t free-speech they were against. The whole trouble came because these venerable institutions were in bad company. A man had been arrested the day before for speaking to the strikers. If others were allowed to speak then the case against him would fall through and encouragement would be given the strike. If the Mayor of Schenectady and the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence and the Bible had stayed at home, they wouldn’t have been imprisoned and broken and soiled. The issue has not been clearly stated to the public. Stripped of its ambiguities it is this–Have the millions of unskilled workers who have borne the ultimate burden of exploitation a right to organize for their protection? Every other issue subordinates itself to this one. The manufacturers have answered that question in the negative and the authorities in Little Falls have handed over the repressive forces to them apparently as completely as though they were employees of the mill corporations.

A brief skeleton of the facts in this connection is of interest. At ten o’clock in the morning of Oct. 14 the Chief of Police gave his unnecessary consent that the writer might speak. At eleven o’clock he withdrew his permission. He said it was contrary to the city charter. When asked to be shown the city charter we were taken before the city attorney, whose first remark was that he didn’t like our looks, and then that he didn’t like what we were going to say. When pressed to tell us what we were going to say, he said he didn’t like what he thought we were going to say! Perhaps it isn’t too much authority to place in the hands of the prosecuting officers to allow them to arrest men for what they think they are going to say, but we beg humbly to suggest that such officers be first obliged to pass some sort of examination in clairvoyance. We then sat down with the chief of police and tried to find for him some section of the city charter which would warrant our arrest. None such was found, but he said he guessed he would “take a chance” on the disorderly section. And so we were arrested and brought into court.

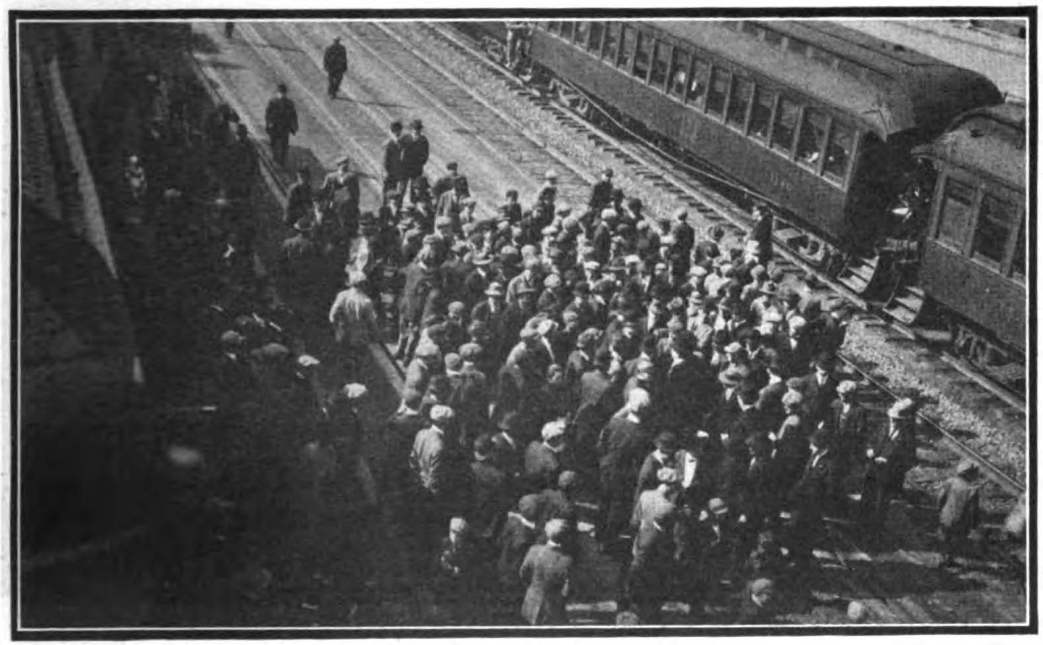

Although Mayor Scholl in a signed statement had said that if Mayor Lunn had spoken anywhere but in Clinton Park it would have been all right, we were arrested and sentenced to jail by Judge Collins for speaking a quarter of a mile from Clinton Park. And then the next day they arrested Mayor Lunn without knowing who he was. The next day five were arrested, and the next four, and the prosecuting attorneys studied the penal code every day after the arrests to find out what it was we had done. One day they came across the riot clause: “where two or three are gathered together,” and the sheriff solemnly read that, and then we came before the automatic court, and so on ad nauseam. And then came the so-called riot, and after it the arrest of more than thirty with the orders of Chief Long to “get the leaders” literally carried out. Every one was held on charges that called for such high bail that these leaders have already been imprisoned these two months and a half.

President-elect Wilson doesn’t believe it is true, but he admits that there is no denying the fact of the people’s conviction that our courts are not courts of justice. What have the people seen in Little Falls to uphold the idea that our courts are courts of justice? What have these “foreigners” seen to inspire them with respect for this one of our American institutions? They have seen practically every person who came in to help them arrested. They have seen the courts back up the arrest. They have seen, they believe, a riot started by the police in order to get an excuse to arrest all the “leaders” and by placing them in prison to break the backbone of the strike. They have seen the program begun by the police carried through the lower court without a hitch. They have seen officers maliciously enter their meeting-place and destroy their property. They have seen their fellow-strikers, some of them women and girls, to the number of ninety, beaten with policemen’s clubs. They have heard their women, young and old, insulted with vile words. They have seen some of their number promised release from jail if they would plead guilty and thus involve the rest. They have had officers tell them that they would not be punished if they would go back to work. They have seen for the last two months and a half fifteen or twenty of their number, whose only crime is activity in this strike against starvation wages, behind the prison bars. And the court of justice–they have seen it sit absolutely blind and deaf and dumb while this organized band of official plug-uglies have plied their trade. It will take a good many sermons and much singing of “America” and many readings of the Declaration of Independence to counteract the influence of that long day spent by more than thirty of us in an underground cell in the Little Falls jail. Among us was one man whose hands had been tied behind him in the mill while his mouth was beaten to a jelly; another had been shot in the head and it took us fifteen minutes to bring him to consciousness but he was left without medical attendance for more than six hours; and there were others whose heads were split open by cowardly officials who dared not beat them in public. When a young Italian asks if the police have any right to hit men that way, and before there is a chance to answer another blow is given, what is the thing to say? That man is insensible to feeling who is not conscious of the tragedy that has taken place when man after man says “they wouldn’t do this way in the old country.” Society is going to learn very soon that those dividends are dearly earned that necessitate the converting of the enthusiasm and patient trust of the foreign-born workers into suspicion and bitterness.

Little Falls stands stripped of her veneer. The flimsy foundations of her boasted philanthropies are perfectly manifest. The churches with their spires pointing to the heavens have followed the earthly course dictated by economic pressure. The line of demarcation between the capitalists with their dependents and the proletariat with their very few middle-class sympathizers is clearly drawn. That hateful word “class” is recognized as a fact based on economic lines. The “good” people of Little Falls know it is false to say “there is no North, there is no South.” They know now the extent to which they will go to keep intact their privilege of exploiting Polish and Italian and Slav women and girls. And Little Falls is ashamed–of being found out.

Little Falls is only a skirmish on the battlefield, but following Lawrence and Grabow it furnishes cumulative evidence of the purpose of the capitalists to crush the uprisings of the unskilled workers by the use of the repressive forces. Ettor and Giovannitti and Emerson are followed by Legere and Bochino and the rest at Little Falls who have been in jail now more than two months. No one, perhaps, knows what will happen to these men, but it is certain that as the contagion of discontent spreads among the unskilled millions the capitalists will have their legislatures pass laws that will make the workers easier victims of the police and militia and courts. We shall not need longer to gasp when constitutional and common law rights are violated, for Little Falls has shown this if nothing else that there is no limit beyond which the capitalist will not go, no right so sacred as to be inviolable when he fears separation from his fundamental source of exploitation-the unskilled, unorganized worker.

But the lesson of Little Falls is not fully learned by a statement of the attitude of the capitalists. A plain word about labor must be spoken. Nothing chilled the atmosphere at Little Falls so much as the attitude of the American Federation of Labor. It was exploited by the capitalists from start to finish. At first it denied that there was any strike. Then, when the employers settled with the workers, it allowed the mill-owners to say the settlement was made with the Federation. It was constantly giving material to the hostile newspapers. Schenectady members of the Federation came to Little Falls and went to police headquarters to get information to discredit one of the strike-leaders, and the writer himself found one member of the Jack-Spinners Union acting as a special police-officer. The churches who had been fighting the strikers the hardest, came out in praise of the A.F. of L. I hold no brief for the Industrial Workers of the World, but I do insist that every strike of the workers belongs to us all, no matter to what labor organization the strikers give their allegiance. Working class solidarity is of more account than all the names in existence. It is the only thing the capitalist fears.

No matter what else is sacrificed, the workers must not be divided.

From the textile mills and garment lofts, from the canneries and coal mines, from the steel mills and the lumber camps comes the cry of the awakening brotherhood of the races–the cry that makes the stagnant blood leap in our veins! On from Little Falls to the skirmish that comes next, and if some be left behind in jail, the spirit that defies the prison walls will escape to cheer you on!

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n06-feb-08-1913.pdf