Yes, this is a Marxist history of upholsterers and their unions you never knew you wanted to read.

‘Upholstering’ by A Stuffer from the Weekly People. Vol. 13 No. 36. December 5, 1903.

The layman, as he is comfortably seated in his cosy chair, little realizes the necessary training of mind and the delicate sense of touch that was once entirely requisite to produce the comforts of a luxurious home. Upholstering is an art handed down from the early ages yea, it can be traced back to the time of “Jabal, son of Lamech,” in the seventh generation of “Adam” and the sixth of “Cain,” who was a tent-maker. But it is not the intention of the writer to trace this branch of the furniture industry from its early beginning, but to take it up in its modern form, since the recent development of capitalism.

Up to four years ago upholstering depended upon skilled labor, such as described at the outset of this article. Prior to then there was a time when the upholsterer was an important member of the community because of his diverse trades. Then upholstering embraced tent-making, undertaking, saddlery, wagon trimming and undertaking. these trades at his command, the upholsterer played an important part. It was an easy matter for him to believe then that he was above other workmen in skill and social standing. He owned the tools of production, and, to that extent, owned his labor power. He therefore, had to be reckoned with in dictating terms.

With the rapid growth of cities under capitalism came a great demand for upholstered furniture, a demand that exceeded the supply. As mechanics were scarce, various schemes were tried to supply that demand. The undoing of the upholsterer was begun at this period. Apprentices were taken on in large numbers and bound to serve three years as such, with little compensation, generally none at all, the manufacturer settling with the parents for one hundred dollars at the expiration of the apprenticeship. With the emigration from other coutries, men paid the manufacturers to learn the trade. That generation of upholsterers and the one following almost lost track of their origin, while the present generation knows nothing of it at all, and the ones entering now will be nothing more nor less than a machine or section hand. Such is the rapid development of the industry under capitalism. With the advent of the apprentices first mentioned, and in the subdivision of labor that took place along with it, the demand of society was satisfied for the time being, as upholstered furniture is a luxury. Then the manufacturer had to devise ways and means to create a new demand for his goods, which consisted mainly of plain work. It was then that tufted work was introduced on a large scale–though tufting on a small scale in the manufacture of upholstered furniture by hand had been in use for over two hundred years-and consisted of the filling and retaining of materials in variously shaped designs (commonly called biscuit and diamond tufting, and consisting of filling such designs with various materials, and the laying of plaits in fabric to be tufted, and of securing such fabric to a suitable backing).

The steadily increasing demand for tufted work in furniture, carriages and other lines of upholstering naturally offered considerable inducement for the invention of a mechanical device for making or doing tufting, and, in 1898. the first successful machine of commercial value was put on the market. A pamphlet issued by the Novelty Tufting Machine Company on December 27, 1902, states that their machines were then in successful operation in “one hundred and thirty-seven furniture, one hundred and forty-two carriage and twenty-four casket factories. These figures do not include the machines of the various other machine companies, working under different patents, that are also in operation.

This means that a great many machines have been put into effective operation in four years. This also means much when we take into consideration the many failures of previous inventions and conditions generally, including prejudices, that had to be overcome; but the time is fast approaching when these features will be entirely eliminated from the field, for the echoes of the coming trust is heard from the West.

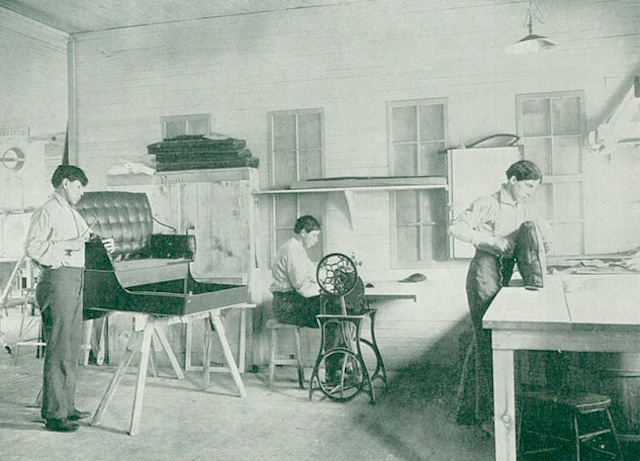

In the aforementioned pamphlet there also appears a photographic reproduction of an up-to-date steel power press In operation, showing class of labor employed”: two young girls standing on two sides of the press, taking off a pad just made, ready for the non-skilled upholsterer to place on his job and finish. “Finish” did I say? Nay, not even finish, for to-day young girls are employed to do even that part of the work that at one time meant a great deal to the mechanic.

Great was the joy of the upholsterer when the announcement of the failure of a machine to do “springing-up” was made Short-lived was that joy, however, for to-day there is in use a simple wire-woven spring ready to be placed in the job by a boy for a few dollars per week, and where this spring is not in use boys are taught to do the springing-up, and in a short time can do it as perfect as the old workers. As this is an important part in the construction of the article, one can see that this change takes the ground from under the mechanic. The upholsterer then takes up the next section and puts his pad on couches and backs on suits, and, where suits are made with plain seats, hands it over to the girls to put the gimp on. By this simple subdivision of labor the output has been doubled with less cost in the manufacturing, and the mechanic is walking the highways and byways looking for a job.

Thus, through subdivision of labor and the introduction of machinery, the passing of the skilled mechanic in the upholstering branch of the furniture industry has taken place, and the skilled upholsterer, an aristocrat of labor, is trembling and wondering “how it happened” and what will become of the skill that has required years of training of mind and adeptness of touch to acquire, and which has been so essential to place him in the front ranks of labor.

But have the upholsterers done nothing to obviate these conditions? Have they done nothing to help themselves?

Yes. Like all other trades, they formed unions to save themselves from destruction, and, like all other unions, organized upon the English method, failed to teach the true principles of unionism, class consciousness.

Race prejudice has well played its part throughout the career of these unions. Failing utterly to understand that capitalism is international, they have arrayed themselves against each other to the benefit of the capitalist class.

The first union of any consequence was organized in 1867-68, with Adam Marx as its president. With the building up of the cities came a demand for upholstered furniture, and the union prospered, so much so that forty hours per week and high hats were the order of the day. The upholsterer reached his highest standard between the years of 1868-72. In May of 72 a strike occurred for a 20 per cent. increase. The manufacturers organized, with C.H. Medicus as their president, and combated the efforts of the men for five weeks. They were compelled to give in, as they had no means of filling the men’s places. But the victory of the men was short- lived. The financial panic of 73 soon rent the union asunder. The division of labor that had taken place was also a factor, for with that division there also came a division in the ranks of the men. Some were known as the custom, and others as the wholesale, workers. This, though a slight difference in the manner of working, soon made a schism in the thoughts of the men, and instead of closing the breach (they failing to see that their interests were identical), it widened it. With this division, and business paralyzed throughout the whole country, the opportunity to sell their labor power became scarcer. No more could one man, or a body of men, leave a shop, seek and find employment in the next. This was now but a dream, a thing of the past.

The Employers’ Association, seeing the opportunity that they had so long waited for, and not having been brought up in the school of pure and simpledom, but knew their class interests, grasped this opportunity and taught a number of men the trade. This increase in mechanics caused the union to soon disappear, and compelled the upholsterer to accept whatever wages the market offered.

Union after union was formed by the men to regain their lost footing, but to no avail, and from 73 to 78 nothing could be accomplished. In 1879 a union was formed with Isidor May as president. It reached its highest sphere in 1886, when the amalgamation of all branches of the furniture industry took place and a demand for eight hours and 15 per cent. increase was made. This strike lasted ten weeks. In the beginning of the trouble the Employers’ Association offered to give 25 per cent. increase, but would not grant the eight-hour day. Through the manipulations of a leading manufacturer, who wormed all the secrets and resources of the union from his men, the union went down in defeat. It was during this period that the trade first saw its Parkism, when Henry Arlers paid $80 as a fine for waiting time.

Another subdivision of labor also took place about this period. Previously a mechanic would finish a whole suit, but now it was sofa-maker, armchair-maker, chair-maker, lounge and couch maker; not only that, but the manufacturers would pick out a few fast men, and set them to work to make the pace. This, together with conditions general after a losing strike, widened the breach between the men, and all efforts to again form a union failed and not until 1891 did it meet with any success. What is left of the union to-day found its origin there. Let us not take up its tribulations, but rather its undoing.

In the early part of 1899 there was in the city of New York Local No. 39. composed of the wholesale workers, and Local No. 44, composed of the custom workers. All were affiliated with the Upholsterers’ International Union. In May of that year a firm named “The National Parlor Suit Co.” moved its plant to Brooklyn. Local No. 39 refused to transfer to Local No. 33 of Brooklyn the jurisdiction of this shop, claiming that trouble was coming, and Local No. 33 could not handle this affair, despite the fact this local had in 1898 successfully carried on a sixteen weeks’ lockout. In the meantime a letter had been received by Local No. 39 from a tufting machine company stating that it was going to introduce the machine in the east and wanting the union to work in harmony with the company. In reply thereto the union’s corresponding secretary, Haas, announced that Local No. 39 would fight the introduction of the ma- chine and “put it out of business.” The company took up the challenge, offered the machine to the “National Company.” and it was accepted. The fight then began, with Haas appointed as manager by Local No. 39. After a few days the management of the “National Company” received a committee of the union, with James H. Hatch as spokesman. proposition of the union was to remove the machine, the “National” to give a thousand dollar bond that it would not use it again. The firm agreed to take the machine out, but balked at the bond proposition; whereat Hatch said: “You can dump the machine into the East River for all I care; but the firm must sign the $1,000 bond.” The conference came to an end, and the machine was taken out the next morning. But Hatch refused to allow the men to return to work, insisting upon the bond issue. This view of the trouble did not coincide with that held by the Brooklyn members of the joint committee, who claimed that, as the machine was removed the cause of the strike was also removed, therefore the men should return to work. This did not suit Hatch, for a victory so easily won would not allow him to show his greatness (sic) as a leader (?) and do damage to the position of living. off the backs of his fellow-craftsmen to which he was aspiring. He fought the proposition of Local No. 33 and told them to “go ahead and take a vote. You cannot do anything, for we outnumber you two to one,” meaning thereby that the members of Local No. 39 would vote the way he told them to; and, as they numbered 600 or more, the 202 members of Local No. 33 would be outvoted.

The view taken by Local No. 33 was upheld by the Executive Committee of the U.I.U., and, in a letter to the members of Local No. 33, its president, Anton J. Engel, said in part:

“But often when victory is won we are baffled or disappointed by the ambitions of some who do not believe there is sufficient glory for them in an easy victory, and, for reasons best known to themselves, through misrepresentations and self-assumed powers, succeed in diverting the proper course, thereby pro longing and possibly defeating the ends originally aimed at. Now this may be done consciously as well as unconsciously. But I am satisfied that it was done consciously and intentionally in the strike of the National Parlor Suit Co., because, being warned and advised by me that the victory or end aimed at had already been gained and nothing further could be gained by an agreement and bond of $1,000. Anyone that has any experience in the labor movement must admit that I am right. For the bond and agreement, even when signed and attested by a notary public, cannot be enforced by a union unless it is strong and powerful enough to enforce it of itself. Courts we know are under the control of the money powers, and Labor is not one of these.” Etc., etc.

Despite the ruling of the Executive Committee of the U.I.U., Hatch & Co. continued to strike. The firm, seeing that the men did not return, brought back the machine, determined to fight to a finish.

Hatch then brought into play the weapons of pure and simple trades’ unionism. The Central Federated Union of New York endorsed the boycott, and while it did frighten some very small East Side dealers, when it came to the large dealers such as Bloomingdale Bros., etc., etc., it had not the slightest effect whatever. It was an utter failure.

One shop after another then took up the machine and the union saw its end, also that of Hatch, who deserted his dupes, and moved to pastures new. Edward Henckler, Social Democrat and a one-time member of the S.L.P. having found no graft in the S.L.P. turned his attention to organizing the custom upholsterers for the purpose “of getting the walking delegateship at $18 per week,” as was said in the open meeting called for the purpose of organizing the craft, which Henckler did not deny. Henckler had about this time succeeded in getting the union formed, when up bobs Mr. Hatch again, who makes his bow and, with the prestige gained at the expense of the wholesale workers, robs Henckler of all his work and is appointed business agent at $25 per week and expenses.

The trade having now advanced to the present prosperous (?) period, and conditions being ripe for an advance along the line, a demand was made and granted.

Intoxicated with so easy a victory, it was decided to take the bull by storm and lock horns with the Dry Goods Association. Accordingly, a strike for increased wages was inaugurated in the leading department stores in September, 1902. Some details of this strike have appeared in the columns of The People. It is still on. But there are other details that have not been published. To get at these let us take up the report that was given to the Fourth Convention of the Upholsterers’ International Union, held at St. Louis, Mo., February 16-21, 1903. President Engel, in reporting as their delegate to the A. F. of L. Convention held at New Orleans, November 12 1902 told of the following

resolution by himself:

“No. 158. Whereas, The Central Federated Union of New York City has seated within its body two unions of upholsterers who have been expelled from the Upholsterers International Union for non-payment of per capita tax and assessments levied by the International Union and the American Federation of Labor, despite the efforts of our International Union to have them unseated; and whereas, these same expelled upholsterers’ unions are permitted to use the prestige of the Central Federated Union of New York City and the American Federation in their attempt to destroy the Upholsterers’ International Union by sending out circulars in which slanderous and dishonest insinuations have been made against the members and officers of the Upholsterers’ International Union and organizer of the American Federation of Labor; therefore, be it

“Resolved, That the Central Federated Union of New York City at once be notified that the United Upholsterers’ Unions at present seated in that body be instructed to affiliate with the International Upholsterers’ Union; failing to comply with this resolution within thirty days’ time after its adoption, the Central Federated Union of New York City shall unseat from its body the two unions of upholsterers; and be it further

“Resolved, That upon the non-compliance of the United Upholsterers of New York City with these resolutions, the organizer of the American Federation of Labor located in New York be and is hereby instructed to proceed at once to reorganize the Upholsterers of New York City into the International Union of Upholsterers.”

Two more resolutions of a like tenor, in which the expelled Hatch unions are accused of attempting to destroy the Upholsterers’ International Union follow.

A committee of the A. F. of L recommended that a conference be called of the U.I.U. and U.U.U. to meet in Washington on Jan. 18, 1903, “to adjust the differences which existed between both organizations.” On the call of Gompers the conference met.

The U.I.U. convention, acting in accordance with the plan of conference, then settled this matter by adopting the following: “Exemption from all dues, assessments, etc., accruing, and claimed by the U.I.U. against these unions since its withdrawal therefrom,” by a vote of 16 in favor and 2 against.

This action brings to mind a few questions. Why did Engel, and the convention, compromise with a fakir, and forgive so easily the sending out of “circulars in which slanderous and dishonest insinuations have been made against the members and officers of the U.I.U.?” and the attempts to destroy the U.I.U.?

It was known that Hatch must affiliate and get the endorsement of the U.I.U. to have the A.F. of L. place a boycott upon the Dry Goods Association, as can be seen from the resolution submitted by Hatch and adopted by the convention.

Did Engel “lay down” because he believed that “the ambitions of some who do not believe there is sufficient glory for them, etc., was a possible rival too secure his due-paying dupes, or did he and Hatch recognize “that birds of a feather flock together?”

On the other hand, why was Hatch so willing to go at the call of, and so anxious to get the support of, Gompers, of whom he said: “When Gompers is seated with his legs stretched under the table and a bottle of good wine within his reach, while dining with such as Oscar Strauss, he cares but little about labor?”

Throughout the whole 29 pages of the U.I.U. convention report not one word appears about the machine that is now reducing the once powerful craft to the condition of the proletarian who must travel from city to country and back to the city again as the seasons come and go, for no longer can he de- pend upon the work in the factory to supply his wants.

But such is trades union pure and simple. This, coupled with the fact that while a strike was on against the firm of J. & W. Sloane, the work was turned out by a firm in Brooklyn, whose shop is the cream of unionism, and that the building trades refuse to strike on houses upholstered by non-unionists, clearly exposes how nobly the class struggle is being waged by the pure and simple fakir-led upholsterers’ union! Upholsterers, awaken from your antediluvian sleep and realize that you belong to a wage working class, a slave class, under the present economic system of capitalism. The census report shows that the workers employed in the furniture industry received in 1890 $488.31 average wages and produced $1,622.57 in value. In 1900 they received $420,31 and produced a value of $1,531.40. But these figures do not tell the whole tale. Though values have decreased, you produce more suits, owing to the cheaper prices at which furniture sells, than in 1890. As a result, your work has been constantly intensified, so much so that the percentage of mortality among cabinetmakers and upholsterers, according to the census, has increased from 15.3 per cent. in 1800 to 18.0 per cent. in 1900. This is only a beginning, with living expenses increased 33 per cent.

Don’t you think it’s time to shake your misleaders from off your backs, so that you can walk erect like men knowing your interests and every ready to strike for the same?

Your capitalist masters know their interests, as can be seen from an address delivered by David M. Parry, of Indianapolis, Ind., president of the National Association Manufacturers before the Furniture Association of America, at the Murray Hill Hotel, on Monday, July 27, 1903:

“And I believe that the time has come when the employers of the country can perform a duty not only to themselves, but to the nation, by coming together in some form of organizations, the ex- press objects of which shall be the upholding of the Constitution of the United States, the inculcating of sane public sentiment and maintenance of free industrial conditions.”

Upholsterers, do you know that “maintenance of free industrial conditions” means that the capitalists shall alone be free to dictate what wages you shall receive and under what conditions you must serve your masters? And the ex- press object of “upholding of the Constitution of the United States” as construed by the master class means that when workingmen go on strike the militia and Federal army shall be sent to shoot down the working class, as was done at Buffalo, Homestead, Wardner, Chicago, Coeur d’Alene, Brooklyn and Victor? Do you recall Captain Miles. O’Reilly’s action at the Thompson’s strike in Brooklyn? And why should it not be so–is it not their government? for “Labor is not one of these.” “But,” say you, “that is a political question, and politics and economics are separate questions.” Nay, all economical questions. are political questions, and therefore inseparable.

Upholsterers, realize that you are no longer “aristocrats,” but proletarians, and must go tramping from city to hamlet meekly begging for a chance to live. Shake off your ignorant, stupid and corrupt misleaders! Join an organization that recognizes the class struggle and that is built and conducted upon lines of knowledge and honesty; that under- stands the issues and steps into the arena. fully equipped, to “summarily end that barbarous struggle at the earliest possible time by the abolition of classes, the restoration of the land and all the means of production, transportation and distribution to the people as a collective body, and the substitution of the co-operative commonwealth for the present state of planless production, industrial war and social disorder, a commonwealth in which every worker shall have free exercise and full benefit of his faculties multiplied by all modern factors of civilization; that is, the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance, and vote for the abolition of this hellish system of wage: slavery at the polls with the Socialist Labor Party. A. Stuffer. Brooklyn, N. Y.

New York Labor News Publishing belonged to the Socialist Labor Party and produced books, pamphlets and The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel DeLeon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by DeLeon who held the position until his death in 1914. After De Leon’s death the editor of The People became Edmund Seidel, who favored unity with the Socialist Party. He was replaced in 1918 by Olive M. Johnson, who held the post until 1938.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/031205-weeklypeople-v13n36.pdf