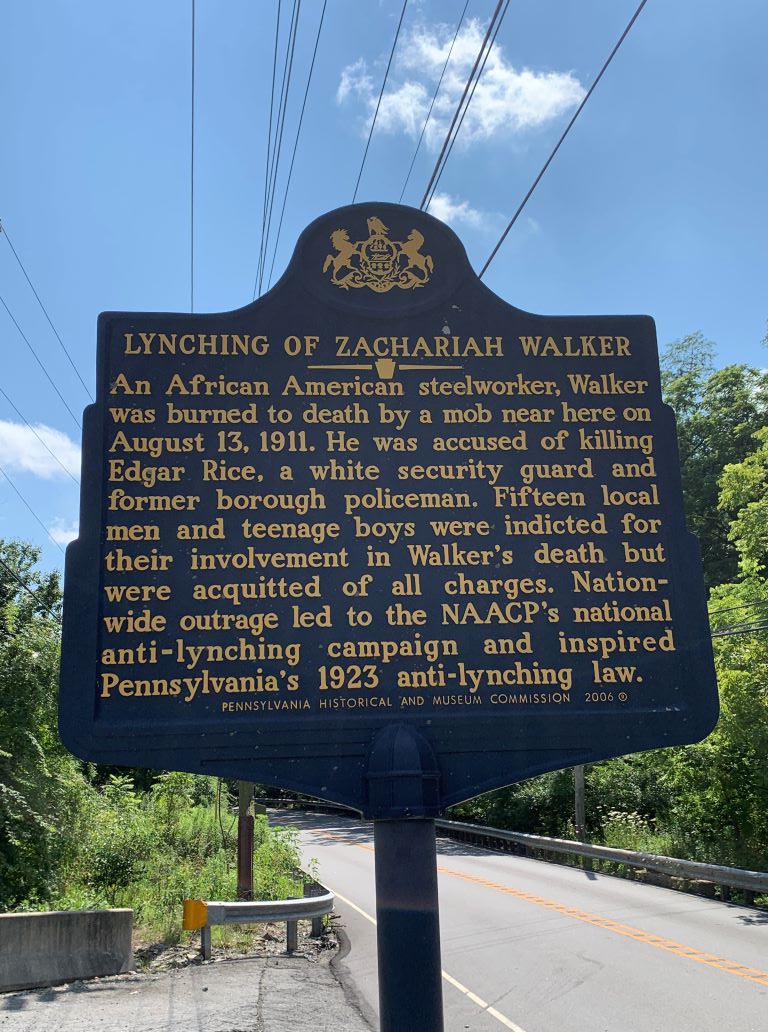

On August 13, 1911, a brutal lynching of Black steelworker Zachariah Walker, taken from a hospital recovering from an attempted suicide after he successfully defended himself in a gunfight with a local policeman, occurred in Coatesville, Pennsylvania. Mary Maclean, the only woman on the Crisis editorial board, went to investigate and resurfaced a remarkable local episode from sixty years before of Black resistance and the class rebellion, for every revolt of the enslaved is a revolt of the proletariat. Known today as the misnamed ‘Christiana Riot’, on September 11, 1851 the determined William Parker, who had previously fled from slavery, was sheltering others fleeing on the ‘Underground Railroad’ when tracked down by their ‘owner’ and his slave-hunting posse. Parker led the successful armed defense with the slave-owner, Edward Gorsuch, the only one to die. With aid of local white Quakers, many made it to Canada with William Parker staying with none other than Frederick Douglass on his way to Buxton, Ontario where he lived into old age.

‘The First Bloodshed of the Civil War’ by Mary Dunlop Maclean from The Crisis. Vol. 2 No. 6. October, 1911.

History is a peculiar goddess. Nothing gives her more satisfaction than to show mankind its capacity for weakness and folly by bringing into juxtaposition two events which set each other off particularly well. Thus, the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln became the scene of one of the most revolting massacres of Negroes in even our annals; and recently she chose Coatesville and August 13 for an exhibition of barbarity toward the black man that is probably unrivaled.

That Coatesville and August 13 made a fitting time and place is due to two facts. First, the entire neighborhood was one of the headquarters of the Underground Railway before the Civil War, and the town itself is named for the Coates family, as true friends as the slave ever had and as active in helping their escape. Secondly, the 11th of September —that is, one month after the man Walker was burned alive—was the sixtieth anniversary of what was called the first bloodshed of the Civil War, in the famous Christiana riot not twenty-five miles from Coatesville.

The “progress” of Southern Pennsylvania and the “settlement of the Negro problem” have been so marked that last month they burned alive an injured black man chained to a hospital bed, at almost the very spot on which, sixty years before, all but month, black and white men had stood shoulder to shoulder to defend with their lives the right of the Negro to freedom. It is an encouraging sign of the times, isn’t it? As Senator-elect Vardaman would say, it shows the North is getting over its mawkish (only he wouldn’t put it so politely) sentiment about the Negroes being human and having elementary human rights.

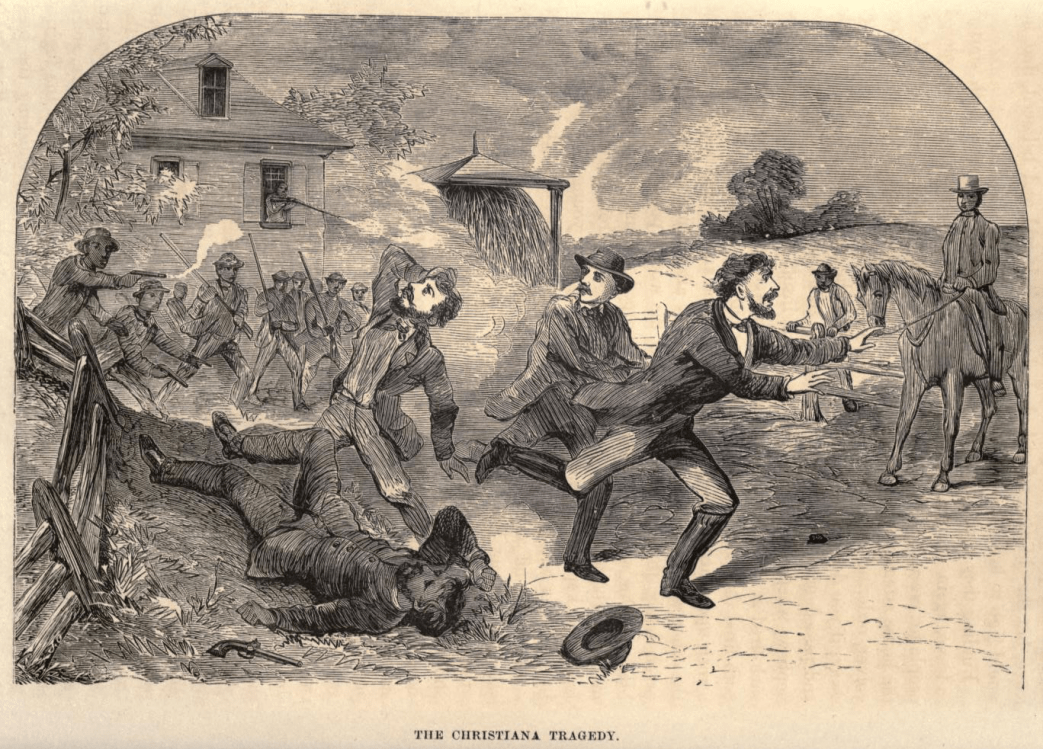

The Christiana riot has not bee widely celebrated, like the Boston massacre, although it bears to the Civil War exactly the same relation that the affair in New England did to the Revolution, but it was of great importance and the unveiling of a monument to commemorate it was celebrated last month by Southern Pennsylvania The lynching was the more popular entertainment, but there were perhaps even more dignitaries at the unveiling.

It is possible that one reason why the Christiana riot has not been more popular a subject for our historians is that black men gathered in quite nine-tenths of the glory. This was not owing to lack of willingness on the part of their white friends to help them, but to the presence among the Negroes of a man of remarkable powers of leadership, who not unnaturally attracted to himself the lightning of the William Parker was his name, and he was something of a figure of romance.

Certain names of colored men and women stand out prominently in the strange annals of the Underground Railway. William Still, chairman of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, and Harriet Tubman, the “Moses of her people,” and others are better known than Parker, because they shared more largely in the organization and devoted their entire time to the work of helping their brothers and sisters from slavery, but nobody could have been braver or more loyal than was William Parker in his less conspicuous way.

He was born a slave but he never intended to remain one. He had no mother and was brought up in a cabin with a crowd of other motherless children who fought and scrambled like young animals. There was this advantage, however. He learned to use his fists, an accomplishment he never forgot. When he was about eleven years old slave traders came to the plantation and William with his chum, Levi, took refuge in a tree while the selling went on. While perched out of sight in the wood the idea of running away came to the boy and he put it to Levi. Levi agreed to go if his mother was sold, but said he must first make sure of that, and William pledged himself to do as his friend did. At last, when all was quiet, the pair climbed down and ran to the quarters.

“Mother, are you sold?” asked Levi.

“No, child,” said the mother, and that ended the question of running away.

In the course of time Levi was himself sold and that left William alone. He reasoned that he was for the most part kindly treated and that as long as this went on it would hardly be fair to his master to run away, but he was decided that the first time he was beaten or there was talk of slave traders he would go. The great day came at last. The master, angered at something Parker had done, struck him violently with an ox goad.

Parker was a giant in strength. He tore the whip from the white man’s hand, beat him soundly with it and then ran for his life. Twice he was nearly caught. Once his pursuers passed within a few feet of him and once a man seized him, but Parker shook himself free, felled the man with his fist, and made his escape before the alarm could be given.

At length he reached Southern Pennsylvania and there he established himself. It was not a very safe place for black men. There was a band of rowdies known as the “Gap gang,” which worked not only to catch fugitive slaves, but also to lay hands on free Negroes and sell them South. Frequently a man would go to the fields and never return. Frequently a woman would start for market and her family would never see her again It was the work of the “Gap gang,” the spiritual ancestors of the “prominent citizens” of Coatesville today.

Parker associated himself at once with the work of the Underground Railway acting with men like Levi Coffin, the one-eyed Quaker who housed scores of runaway slaves and could spy out a slave hunter quicker than other men with the normal number of optics, and Lindley Coates, the “president” of that section of the railway, and Still, the colored post-office clerk of Philadelphia, whose spies were everywhere, Parker helped slave after slave to freedom.

In Maryland there lived a man named Gorsuch, not a bad-hearted man, but violent of temper and tenacious of his “rights,” even when they cut pretty deeply into other people’s. Gorsuch had a son, Dickerson, of a gentler turn of mind. Together they took care of a large plantation worked by many slaves.

When he heard that some of these slaves had run away the older Gorsuch burst into a fury. He would have his property back; he would have his rights; he wouldn’t let the thus-and-so n***s get away from him—ungrateful black hounds after all he had done for them— and so forth and so on. Dickerson endeavored to calm him. Perhaps deep in his heart he felt that if things were reversed he would himself rather strike for liberty. At any rate he tried to dissuade his father from following the fugitives, but the old man would not tolerate the idea of staying at home and the son dutifully went along with him.

The runaways had reached Christiana and were hidden in the house of Parker. On the night of September 10 the Gorsuches had reached Christiana but not unannounced. In Philadelphia William Still was chairman of the vigilance committee. Throughout the South he had agents who worked with the slave catchers and kept him well informed of their plans, and one of these spies was attached to the Gorsuch party. He separated from the slave hunters just before reaching Christiana and brought word to Parker that his guests were being sought.

It was after midnight when Edward Gorsuch and son rode up to the house of Parker, accompanied by United States Marshal Henry H. Kline. Upstairs the slaves lay hidden, and Parker, with his two brothers-in-law, Alexander Pinckney and Abraham Johnson, were awaiting the attack. It should he explained that Parker had worked out a theory of his relation to the Fugitive Slave Law. He seems always to have thought out the arguments for and against whatever he did, and he had quite decided that he owed no respect to the laws of the United States. If the law did not protect black men, black men were not bound to regard it, he said, to the scandal of even his radical white friends.

So when Kline called on him to surrender his reply was very ready.

“I am a United States marshal,” announced Kline.

“I don’t care for you nor the United States,” returned Parker calmly.

Somewhat disconcerted Kline withdrew for a consultation. Gorsuch was for violence, but Kline, more especially as it was his business to enter the house first, was less eager to begin the fight. They waited for some time.

The first light of dawn was showing, and Mrs. Parker asked her husband if she should not blow the horn. The blowing of the horn was the signal to the colored men of the neighborhood to rally for the protection of their friends, and Kline knew what it meant. As soon, therefore, as the horn sounded he shot at the woman. She knelt beside the windowsill and continued to blow to the accompaniment of bullets from the men below.

The sound of the horn on the quiet morning air went far, and soon from one side came the forms of black men running to the rescue and from the other, galloping out of a wood, members of the “Gap gang,” ready to take what advantage there might be in the fortunes of war. The situation would reach a climax in a few minutes.

Parker, whose courage alone had kept up the two men with him, opened the door and stepped out. Edward Gorsuch pointed a pistol at him, but Parker stepped up and laid his hand on the old man’s shoulders.

“I’ve seen guns before now,” he said, and he added: “I don’t want to do any harm.”

Then he precipitated the fight by remarking to Gorsuch, who was a very “religious” person:

“Old man, you ought to be ashamed of yourself to be in this business, and you a class leader at home.”

Dickerson Gorsuch stepped forward angrily.

“I wouldn’t take such an insult from a damn n***r,” he said.

Thereupon Gorsuch fired. The bullet grazed Parker’s head and at the signal the fight—the “first fight of the Civil War”’—began.

It ended with the victory of the black men, but Edward Gorsuch lay dead on the ground and Dickerson had fallen, severely wounded, beside him.

During the fight three Quakers, Elijah Lewis, Eastner Hanway and Joseph P. Scarlett, had ridden up. After the fight Levi Pownall, a Quaker whose house was one of the most important stations of the Underground Railroad, arrived and took the wounded Dickerson into his charge. Parker asked what he should do and Pownall told him that his only chance lay in immediate escape to Canada, which the Underground Railroad could effect.

Dickerson Gorsuch was in many ways a typical Southerner of the best type. He asked whether Parker had been hurt, and when he was told he had not been injured said:

“I’m glad. He is a noble Negro.”

What he could not understand, however, was that his “boys,” the fugitive slaves, should have fought against him even in an attempt to gain their freedom. He could not grasp the limitations of the patriarchal system any better then than many well-disposed Southerners do to-day.

The same roof that sheltered young Gorsuch was also a refuge for Parker, Pinckney and Johnson. Pownall smuggled them in, dressed them in the best of clothes and sent them walking casually out of the front door with the ladies of the house. In the darkness the guards who watched the place could not see whether they were black or white, and there was no suspicion that the careless gentlemen were the ex-slaves whose arrest was sought.

An order was issued for the arrest of Gorsuch’s fugitive property, giving their aliases. On the list appeared, as aliases used by them, the names of Parker, Johnson and Pinckney, although they had long been free Negroes. This device, however, did not succeed, for the three men, who had been joined by a fourth whose name is not known, were safe in the house of Isaac Mendenhall and his wife, two of the staunchest friends of the slave in that region. There they spent the first night of terror, and the plan was to take them on, as was the custom of the “railroad,” to the home of John Vickers, but Mr. Jacob L. Paxson, of Norristown, took charge.

It was better, he said, to take them to the home of Graceanna Lewis, instead of the more notoriously abolitionist resort. In the garret of Graceanna Lewis’ house, therefore, they hid for a day or two, and since the cook was not quite trustworthy food was secretly brought in from a neighbor’s house.

A friend called at the house one evening, and the dawn saw him well on his way to market at the next town with sundry “tubs of butter,” covered with cloth in the bottom of his wagon. These “tubs” were delivered at a carpenter’s shop in Norristown, as arranged by Mr. Paxson. For four days the men hid under a pile of shavings. Food was passed to them at night on a long shovel over a four-foot alley. On the fifth day five wagons exactly alike drove out of Norristown in different directions. In one of them lay Parker, Pinckney and Johnson, with their companion Suspicion had been pretty well diverted by this time, and if a description of the wagon was sent out there were four to distract attention from the important one. The men reached Philadelphia, were taken in hand by Still and were forwarded to Canada.

Parker’s wife and child, however, were caught by the slave hunters, presumably, for they were never heard of again. They claimed that she gave herself up voluntarily. Anyway, she disappeared.

While all this was going on the three Quakers, Lewis, Hanway and Scarlett, and thirty-five Negroes had been arrested, charged with treason. The treason consisted in not assisting a marshal of the United States to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law by helping him capture the runaways in the house of Parker. They were taken to Moyamensing Prison and lay there for ninety-seven days while the State worked up its case against Hanway, the first of their number to be tried.

Theodore Cuyler defended the prisoners and Thaddeus Stevens advised him. The feeling of the community was strongly against prosecuting the accused men, and Mr. Cuyler put the popular verdict in regard to the case clearly when he said to the judge:

“Sir, did 3 hear it? That these harmless non-resisting Quakers and thirty wretched, miserable, penniless Negroes armed with corn cutters, clubs and a few muskets and headed by a miller in a felt hat, without a coat, without arms, mounted on a sorrel nag, levied war against the United States? Blessed be God that our Union survived the shock.”

In fifteen minutes the jury brought in a verdict of not guilty. The prosecution changed the charge against the whole group to one of riot, and they stayed in jail for some time until the grand jury refused to consider the charge, and the entire case fell to the ground.

Thus, near Coatesville, did black men fire the first shot of that great war, which, ten years later, was to give them freedom.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1911-10_2_6/sim_crisis_1911-10_2_6.pdf