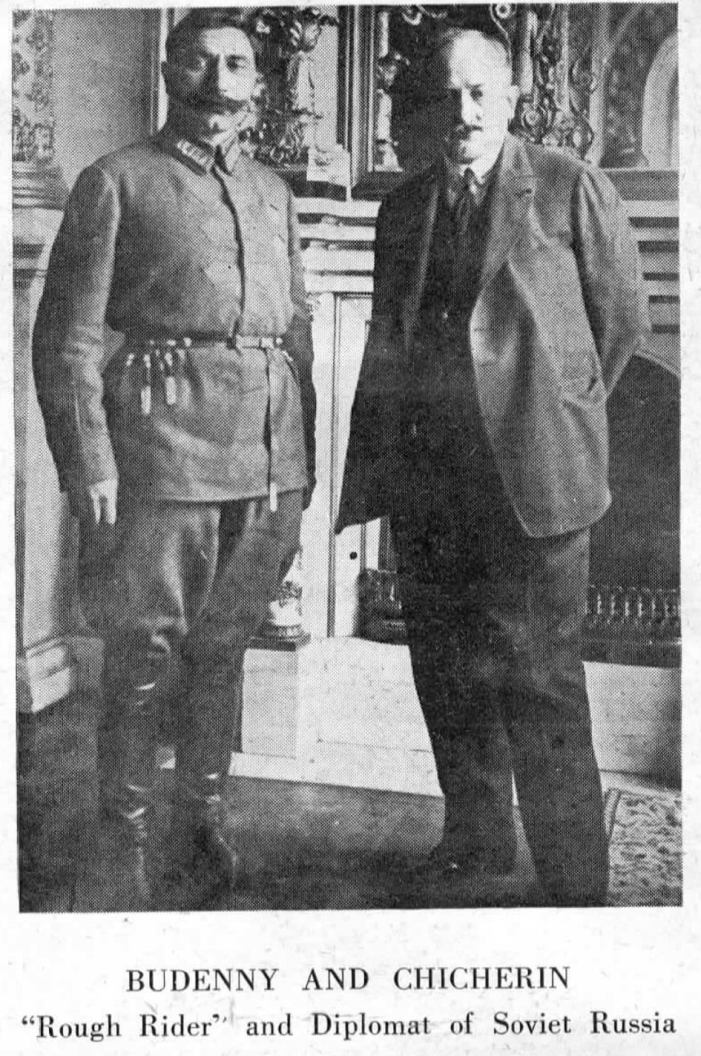

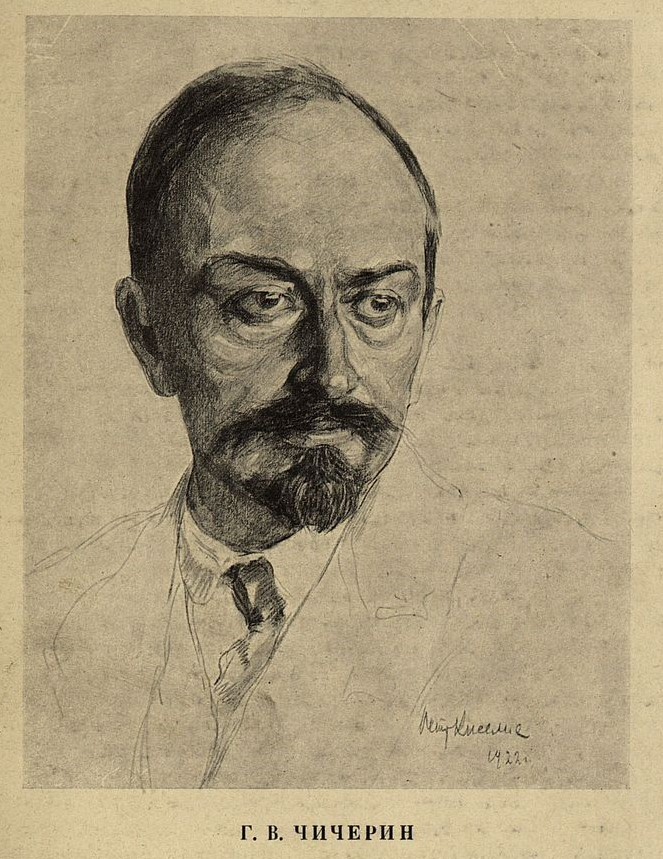

What can be the diplomacy of a revolution? What kind of revolutionary is a diplomat? And what diplomat is a revolutionary? The comrade with, perhaps, the most difficult job of any Bolshevik was the enigma, Georg Chicherin. Tasked with an impossibility; peace between the Soviets and imperialism, Chicherin the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs gives a report to the Fifth Soviet Congress July, 1918 on the first year of that effort. The full report, an essential document in the diplomatic history of the Soviet Union, below.

‘Socialist and Imperialist Diplomacy’ by Georgi Chicherin from The Proletarian Revolution in Russia edited by Louis C Fraina. Communist Press Publishers, New York City. October, 1918.

During the period that followed the signing of the Brest-Litovsk peace, we find that our foreign policy developed along different lines than those followed during the first few months after the November Revolution. The basis of our foreign policy since the end of 1917 and the beginning of 1918 has been a revolutionary offensive.

This policy kept step with an immediately expected World Revolution for which the Russian November Revolution would have been the signal. It was especially meant to reach the revolutionary proletariat of all countries and to arouse them to combat Imperialism and the present capitalist system of society. (We remind our readers that at this time until the peace of Brest-Litovsk, not Tschitcherin, but Trotzky, was People’s Commissaire for Foreign Affairs.)

After the proletariat of other countries refused their direct support for the destruction of revolutionary Russia, our foreign policy was radically changed through the occupation of Finland, the Ukraine, the Baltic Provinces, Poland, Lithuania and White Russia by the armies of German-Austrian Imperialism. In the last four months (March to June, 1918) we were compelled to make it our object to avoid all the dangers which menaced us from all sides and to gain as much time as possible: in the first place, to assist the growth of the proletarian movements in other countries, and in the second place, to establish more firmly the political and social ideals of the Soviet government amongst the broad masses of the people of Russia and to bring about their united support for the program of the Soviets.

Soviet Russia, with as yet no force sufficient to protect its own boundaries, surrounded by enemies waiting for its downfall, suffering from a period of unbelievable deterioration caused by the war and Czarism, and always cognizant of the dangers which threatened it at every step, had to be constantly vigilant in its foreign policy. The policy of delay was possible thanks to the diversity of interest, not only of both coalitions (the Central Powers and the Allied Powers), but also within each of these groups and in the respective Imperialism of all the warring countries. The position on the Western Front (Belgium-France) bound the powers of both coalitions temporarily to such an extent that neither of the two decided to aim at the direct and entire destruction of Russia.

A section of these imperialistic groups in both coalitions thinks of the future, of after the war, of economic relations with Russia, with this world market so especially ripe for development. This element in both coalitions would prefer a compromise instead of an annexation policy for the sake of economic advantages. The hope to embroil Russia in the war, while her army is not built up, plays a part in the calculations of both coalitions. The military party in each group would prefer an attack for the suppression of the Soviet government of Russia.

The Soviet government, although it had decided upon a waiting policy because it did not strive for a war of revenge, was, nevertheless, compelled, after the peace of Brest-Litovsk, to work for armed resistance and at the same time to reckon with those elements who were opposing the war parties. These elements are as yet weak and we are not able to strengthen them through our own military power. The ever-growing proletarian movement has it as yet come to a climax and therefore our report is a grave and serious one. A report about our retreat, about the great sacrifices which we make in order to give Russia an opportunity to get on her feet, to organize her forces and to wait for the moment when the proletariat of other countries will help us to bring the Socialist Revolution of November, 1917, to a successful conclusion.

The period following the signing of the Brest-Litovsk peace is characteristic because the German offensive was not marked on the whole Eastern Front by a distinct line. Finland and the Ukraine were free of Soviet troops, but the masses of these parts continued the struggle. The Entente Powers withdrew during this time their entire military support, at the same time remaining as ruler in places from which they should have withdrawn. As a momentary proof that the relations between Russia and the Central Powers were changed to ordinary peaceful relations, we must point to the arrival of Count von Mirbach [who was afterwards assassinated by Russian counter-revolutionists] in Moscow on April 23, 1918, and the arrival of our Russian comrade, Joffe, in Berlin on April 20, 1918.

Concerning the former allies of Russia, we must look upon the landing of Japanese troops in Vladivostok on April 5, which landing was, nevertheless, accompanied by assurances from Japan’s allies that this fact was not meant as an attempt to interfere in the internal affairs of Russia. In the meantime a great section of the English and French press was carrying on propaganda for the occupation of Russia under the slogan that such intervention was meant for the saving of Russia. But the governments of the Entente Powers adhered to a very careful policy regarding Russia, especially did the government of the United States of America adopt a decidedly friendly attitude.

The time which now followed was indeed critical with regard to Germany. The German-Finnish and the German-Austrian armies after having occupied the whole of Finland and the Ukraine, invaded the territory of the Soviet government and came face to face with Soviet troops, so that there were continuous skirmishes along the whole line of demarkation and Petrograd was directly menaced. The White Guards (Finnish counter-revolutionists) led by Germans drove into Murman territory and Port Ino, the key to Petrograd, was in grave danger. At the same time the German army continued its march on the Ukraine front into the governments of Kursk and Woronesj, into the Donnetz basin and on the river Don. In the south the Germans occupied the Crimea and, continuing their march beyond the Don, attacked Batoisk (opposite Rostov on the Don valley, near Azof). Counter-revolutionary lands forced their way into the Don and Kuban districts (the western part of the north Caucasus) under the protection of the Germans.

At last the German troops landed in the vicinity of Porte (harbor in the South Caucasus on the Black Sea) while the Finnish troops on the other side began their march in the Caucasus in the direction of Baku (on the Caspian Sea). This critical period was settled on the Finnish frontier by an agreement between the German and the Russian governments concerning a basis for a treaty between Russia and Finland. A gradual relaxing of military skirmishes on the Ukraine front was directly noticeable, caused by the beginning of peace negotiations in Kiev between Russia and the Hetman government.

The result of our so sharply conducted political dealing was: the retreat of that part of the Russian fleet (the Black Sea fleet) to Sebastopol and from there it sailed to Noworossysk (the harbor of the German menaced Kuban district). The demand for the return of this district was considered as an indispensable condition to territorial, as well as political and economic relations between Soviet Russia and German Ukraine.

Up to this moment (beginning of July, 1918) the most critical question gems to concern the Caucasus and can be attended by grave consequences, also the crisis in the Don, where counter-revolutionary activity is not yet settled. But the retreat of the fleet to Sebastopol made it possible for the nixed commission in Berlin to commence its work. This commission was made up of two parts: one a financial and judicial committee whose work consisted in planning a basis for peaceful economic relations between Russia and Germany; the other, a political committee whose task it was to solve the questions arising out of the Brest-Litovsk treaty.

The new negative moment in the relation between Russia and her former Allies was the uprising of the Czecho-Slovaks. In this case it developed that the governments of the Entente stood with those elements who, like the Czecho-Slovaks, served to support the counter-revolution in Russia.

Directly after these events followed the landing of English troops on the Murman Coast and in the press and the declaration of the diplomats the question of intervention becomes more pronounced. But those elements in the Entente countries whose aim is to reach a complete and friendly relation with Soviet Russia continue their struggle, and reveal at the same time the extraordinary shortsightedness of the policy of attacking Russia. Thus we see how complicated the problems are that the Soviet Commissaires are called upon to solve; we have been careful in our deliberations to avoid all dangers which would lead to irreparable actions from the side of our opponents, and have taken all possible steps to bring about a peaceful solution of our difficulties with both coalitions.

The relations of Russia to the states of Central Europe were determined by the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and the principal part of our policy in relation to Germany was to execute this treaty. The indistinctness. the as yet undecided agreements and the imperfection of the treaty of Brest encouraged the exponents of the annexationist policy to develop this policy still further, with regard to Russia.

The treaty of Brest is not distinct as to the boundaries of the territory occupied by Germany, and yet it determined that at the moment of the signing of the treaty all further progress should cease. The treaty leaves the situation of territories occupied by Germany an open question. The territory of the Ukraine is not defined, and the question of the boundaries of the Ukraine, together with the uncertainty of where the German troops would stop, was an extremely dangerous one. The indistinct, contradictory, and somewhat impracticable stipulations concerning the Russian ships create the possibility for new demands from Germany and the Ukraine upon Russia. Be sides there was the possibility of going still further than the stipulations. under the pretext of “self-determination.”

The simplest method was to accept a fictitious “right of self-determination” in the regions occupied by Germany. In fact, we had already received a report concerning the “self-determination” of Dvinsk (on the railroad from Warsaw to Petrograd and from Riga to Moscow, Warsaw in Poland and Riga in Courland being under German control) who desired to become part of Courland. We also heard from the delegation in the White Ruthenian regions (the governments of Grodno, Vilna, Vitebsk, Smolensk, Mohilef and Minsk-the region between Warsaw to a short distance from Moscow) that they wished to withdraw from the sovereignty of Russia.

Section 7 of the treaty of Brest provides that a special commission determine the boundaries of those regions that withdrew from Russia. When this commission convened at Pskov (between Dvinsk and Petrograd) it was empowered, by the consent of both governments to determine definitely the boundaries of the regions occupied by Germany. However, after the first session of this commission, their work was interrupted, and has not been continued since.

The following proposition was submitted by the Germans: that the basis for the right of self-determination be established on the boundaries German occupation; that every landowner whose land was bounded by the German line of occupation should have the privilege of deciding to which side (Germany or our side) his property should belong in the future. The solution of this question of principle was referred to Berlin, where the Political Commission (a mixed commission of Soviet representatives and Germans) will be occupied with it.

The position of the occupied regions is not as yet clear. The German government informed us that the railroad employees would retain their former wages, and enjoy all advantages as to the division of the necessities of life and that malicious agitators were spreading rumors amongst the employees that all those who continued their work under German occupation would lose their employment, their pension, and all their savings when later the now occupied territories were restored to Russia. Therefore, the German government requested us to send a public notice to the occupied districts. containing the information that these rumors were baseless and that the Russian government recommended that the railroad employees continue with their work. However, we found upon direct information that the wages of the railroad employes were reduced fifty per cent, and that these employees and all other officers were subjected to all kinds of persecution and that they did not enjoy advantage in regard to the necessities of life.

We informed the German government that we could not take any part in the responsibility of the administration of the occupied district as long as the German government insisted upon deposing all Soviets and continued to destroy traces of the Soviet system. The question of the internal administration of the occupied sections had also to be referred to the Political Commission in Berlin.

The military advance of the Germans after the treaty of Brest-Litovsk occurred in two directions: in Finland and in the Ukraine. After the Russian Republic had submitted to the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk and had recalled her troops from Finland, there remained in Finland but few Russian citizens who, upon their own responsibility, took part in the struggle of the Finnish working class. At the moment of the invasion of German troops into Finland, and after, we received continual threatening notes from the German Government claiming that we had sent troops and munitions to Finland. But every time when the occupations complained in the notes were investigated we found that in reality they did not exist. They merely served the Germans as a pretext for delaying the cessation of military measures. The notes served to justify the government of the Finnish White Guards when they refused to liberate the Russian citizens, Kameniev, Sawitski and Wolf, who were returning from Sweden and were arrested at the Aland Islands. The Finns pointed out our violations of the Brest-Litovsk treaty when band of White Guards invaded Karelie and the Murman regions, the south-west half of the former having been a part of Russia for two hundred years, and the later being wholly Russian.

The German government constantly reminded us that we are compelled, according to the treaty of Brest, to reach an agreement with Finland, and the Russian Soviet Government declared their willingness time and time again, despite the extreme provocative acts of the Finnish White Guards. I remind you of the shooting of thousands of Russians in Wyborg, of the many executions of Russian citizens, even of official members of the Soviets in Finland. I remind you of the arrest of Kowanko, the commander of Sveaborg, the Russian fortress of the Island of Helsingfors, the capital of Finland, of whose appointment Finland was duly informed through our representative ad interim and the agency of the German government. Kowanko was arrested immediately afterwards and had to submit to an investigation, and up to this date, July 19, 1918, has not yet been liberated. I remind you also of the violent seizure of the Russian ships by the Finns, of the seizure of the hospital ships, also of the enormous sums of money, amounting to many billions, taken from the safes of the fortress and the vaults of the Russian exchequer. Notwithstaning, the Russian government declared itself willing time and time again to negotiate, not only as an answer to the German demands, but the Russian government addressed itself directly to Fin- land with a proposition which was never answered.

The question of our relations to Finland was especially acute when an important German-Finnish army on one side advanced towards the Russian frontier near Bieloostrov (directly northwest of Petrograd) and the German government on the other side questioned us concerning the presence of English troops in the Murman district (which territory, as mentioned above, the German-Finnish White Guards had invaded) in this inquiry, the number of English troops was grossly exaggerated by the German government. In May, the question of Fort Ino became the most prominent, when the German government followed the example set by the Finnish High Commander and demanded the surrender of this Russian fort to Finland. This took place in the general critical period of the advance of the Germans, after the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, when the German troops advanced into the governments of Woronesj and Koorsk (in which governments the rivers Donetz and Don enter the Azov Sea) and the end of this advance could not be foreseen. Our notes to the German government at the later part of April and the beginning of May, containing pressing inquiries as to their exact intentions in relation to Fort Ino, resulted in the commencement of negotiations to reach a compromise. (Note: Fort Ino is one of those forts which threaten Petrograd).

When, despite the negotiations, the Finnish troops demanded the immediate surrender of Fort Ino, and the Fort was destroyed by the retreating Russian troops, the German government at last proposed as a basis for an agreement with Finland: the return of the town Ino, upon the condition. that this place and the district Ravoli (on the railroad exactly N.W. of Petrograd) in the vicinity of Bjeloostrov should not be enforced by the Russians, and upon the condition that we abandon the western part of the Murman regions, which the Germans and Finns had invaded, to Finland. Our acceptance of this as a basis for an agreement led to the discontinuation of the critical situation of May. However, notwithstanding this, Finland still continued to refuse to answer our proposal to enter into mutual negotiations.

The separation of Esthonia and of the northern part of Courland from Russia is in no way the result of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, because this treaty only provided for the temporary occupation by Germany of these parts. Already on the 28th of January there was delivered to our representative Worofski in Stockholm a declaration from the land owners and barons of Esthonia and Courland concerning the independence of these provinces. After that, meetings of the landowners and barons were held in Esthonia and Courland, and in Riga, the capital of Livonia, on March 22, and at Reval, the capital of Esthonia, on March 28, theiy decided on the convocation of congresses. These congresses were held in Riga and Reval on April 9-10, and they accepted the declaration as to the separation from Russia. On the 19th of May, our representative Joffe received notice to that effect through the office of the German Minister of Foreign Affairs.

In his note of May 28th, addressed to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Joffe called attention to the fact that the action taken in Riga and Reval was in reality but the expression of a comparatively small part of the people of Courland and Esthonia and that only by a real and general unhampered expression of all the people, under the condition, could the basis of self-determination and separation be decided.

The Russian government was but lately confronted with the question of its relations to Poland, when the representative of the Polish Council of Regents, Mr. Lednitzki, came to Moscow, and in his position as representative of Poland, desired to enter into relation with the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. On his first visit, we found his credentials unintelligible, but when he came the second time, he came with the formal authority of the Council of Regents to negotiate with us, concerning matters regarding Poland. However, we do not recognize the present situation in Poland as politically independent, and therefore cannot consider the Polish government as expressing the will of the people.

We entered therefore into relations with Mr. Lednitzki, but, as is self explanatory, only in essential, not in diplomatic relations, and then only when Count Mirbach, who was at that time the German ambassador in Moscow.

informed us that by maintaining such relations we would gratify an expressed wish of the German government.

A more intense German offensive on the Ukraine side would have been more threatening than the advance upon the side of Finland. Directly after the conclusion of the treaty of Brest the troops of the Central Soviet government were ordered to withdraw from Ukraine. The Soviet government was maintained within the borders of the Ukraine, which, after the second congress formed itself into the government of the independent Soviet Republic of Ukraine. After the German troops had occupied all points belonging to the Ukraine, they continued to advance still further in the direction of Moscow and even occupied the southern part of the Russian government of Tversk and Woronesj.

Therefore, the question of determining a line of demarkation on the Ukrainian front, which would determine the limits of the German advance. was quite acute, especially on the front near Woronesj, where Germany first demanded the occupation of some districts, but later only the occupation of the Wologodski district, with the important strategic railroad junction of Woronesj. The question of the line of demarkation was closely connected with the question of cessation of hostilities, and this was the beginning of negotiations with the Ukraine.

On March 30, the Ukrainian Rada addressed us with the proposition to commence negotiations, and the German government repeatedly pointed to our obligations as laid out in the treaty of Brest to conclude a peace with the Ukraine. From our side, we proposed opening negotiations at Smolensk (between Moscow and Brest). Although we sent our proposition directly to the Rada in Kief, and also to Berlin, our proposition did not reach the Rada in Kief soon enough, and it was not until April 16th that the Rada sent us a courier with a note proposing to conduct the negotiations at Tversk (halfway between Moscow and Kief), to where our delegates rapidly departed.

The peace delegation of the Ukraine came but to Worosjby (half way between Twersk and Kief), but the constant hostilities made it impossible for the delegates to meet. At this time, the Kief Rada was displaced by the government of Skoropadski, and Germany insisted that the negotiation be transferred to Kief, where they commenced on May 22nd.

The first question to be acted upon was the question of an armistice. The most important question, however, was the determination of a line of demarkation. We had repeatedly in the past made the question of determination of the boundaries of the Ukraine a topic for discussion as we considered this matter as most important, having to reckon with far reaching consequences in case of an unfavorable conclusion.

On March 29, we received a telegram from the German assistant secretary Busche, in answer to our queries, explaining that the territory of the Ukraine was temporarily determined upon, nine governments being added to the Ukraine.

When the negotiations concerning an armistice started, the Ukrainians demanded much more. They demanded that the line of demarkation be extended further to the North and to the East, so that they occupy eight more districts. They wanted especially the government of Woronesj, making fourteen districts, with a population of three million, to be given them.

The extreme moment in the negotiations occurred simultaneously with the critical moment in the South, with the critical moment upon the Black Sea, when Germany demanded that the Russian fleet near Novorossisk return to Sebastopol. The Germans did not limit their military forces to the nine governments added to the Ukraine on March 29th, but occupied Taganrog and Rostov on the Don (both of the Sea of Azof) on May 6. Their further advance came to a halt at the important railroad junction Batarsk (opposite Rostov on the Don), which was occupied by a Soviet army.

On April 22, the German troops had already invaded the Crimea and had more extensively occupied the peninsula of Tauri, while a certain part of our Black Sea fleet had time to leave for Novorossisk. We received a number of notes from Germany, wherein she complained of hostile treatment in different places upon the Black Sea, where ships belonging to our Black Sea fleet were destroyed.

On the South, the Turkish army advanced into the Caucasian regions, occupied Alexandropol (south of Tiflis) and threatened Baku, while southern Trans-Caucasia sent troops against Soviet Russia, against the adherents of the Soviet movement in the vicinity of Suchum (in South Caucasia on the Black Sea), and in the entire Abchasie (South Caucasian Mountain region). The advance of the Germans and their allies in the Kuban regions (the western part of North Caucasus) had already started.

And in this critical moment the demand was made of us to order the return of the Black Sea fleet from Novorossiesk to Sebastopol.

As a result of further negotiations, we received the guarantee from Germany that the ships would not be used during the war and after the conclusion of a general peace they would be returned to Russia. At the same time, the troops would not advance further upon the entire line of demarkation on the Ukrainian front, which was similar to the real position of the occupation at the beginning of the Ukrainian negotiations, which did not extend beyond Walveki upon the Woronesj frontier at Batasjk (opposite Rostov) upon the Southwest frontier. In case we refused, the advance to Kuban would continue, and besides we were told that the possibility of economic and political agreements, the order to cease all advances upon Ukrainian frontier, and even the beginning of the work of the joint commission in Berlin, depended upon our consent to the return of the Black Sea fleet from Novorossisk to Sebastopol.

The question of the return of the fleet thus became the centre of the whole German diplomacy against us, so that they might influence the whole further progress of our relations. The return of a part of the fleet to Sebastopol on June 18 and the sinking of the rest on June 19 made an end of this critical event.

Quickly upon this, the commission in Berlin, which had not convened for a long time, began to hold sessions, and the advance of the German troops upon the Ukrainian front ceased. The negotiations progressed even more rapidly. Three days after our consent was obtained for the return of our fleet, on June 12, a general armistice with the Ukraine was concluded. On June 17, an agreement concerning the line of demarkation of the Northern Ukrainian front was arrived at, and representatives were sent to Vitebsk to determine upon this line of demarkation. The most important point in the peace negotiations was the question of the boundaries of the Ukraine.

was agreed that the fate of those parts over which no agreement could be reached should be decided by a referendum, held under conditions that would guarantee the free and unhampered expression of the people.

The advance of the Turks, and later, of the Germans, in the South, was made easy through the policy of the Trans-Caucasian government (Social Revolutionary and Menshevik) a government supported by the privileged classes of the population, who had adopted a hostile attitude toward Soviet Russia After the attempts of the Russian Soviet government to enter into communications with the Trans-Caucasian government did not materialize, Germany offered her mediation for “regulating” the relations between us. After we had agreed to this, Count Mirbach proposed that we send our delegation to Kief for the negotiations with the Trans-Caucasian government. However, we proposed that we meet in Vladikavkas (in Caucasia) and we insisted that the negotiations be directly between the Russian Soviet Republic and the Trans-Caucasian government. Finally Count Mirbach informed us that the representatives of the Trans-Caucasian government, Vatshabelli and Tseretelli, were on their way to Moscow. and that the German government cherished the urgent wish that the negotiations between us commence.

But the Trans-Caucasian government collapsed. The Georgian National Council, which took the place of the government of Tseretelli, sent a representative, Mr. Khvendadste, to Moscow, with whom, however, we did not start negotiations. We knew that the government of the independent Georgians represented only the privileged class and that the masses did not wish nor recognize the separation from Russia. We also received the report that fictitious representatives of the Mussalmen of Askhabad (the Trans-Caucasian region bounded by Persia) represented themselves as an independent government, while we knew very well that the masses of the people did not wish to separate from Russia. The German government also informed us of the contents of a manifesto of a government of the Union of Mountain Tribes of North Caucasia, with the proclamation of their independence, while in reality, North Caucasus was in the control of the adherents of Soviet Russia, who rejected the proposition.

The independent Georgians permitted Germany to transport her troops over the Georgian railroad, which opened the way to Baku, on the Caspian Sea, for Germany.

The Turkish troops were, as we know, in the Armenian regions, in the beginning of July, 1918, where a strong Armenian movement was operating against them.

The question of the Caucasus was placed upon the order of the day of the Political Commission convened at Berlin (German and Soviet representatives). The question of economic relations between Germany and Russia was determined on one side by the necessity for the liquidation of losses through Czaristic war measures and through the social legislation of the November revolution in regard to German property in Russia, and on the other by the necessity for the creation of mutual economic relations in both countries. The treaty of Brest-Litovsk obligated us to pay indemnity for the losses of German citizens during the war through the liquidation of their undertakings, or through the cessation of payments of dividends and interest on loans. The execution of these obligations demanded from us the creation of a department that should investigate the German claims. This department is now in existence as the Liquidation Department of the People’s Commissariat of Trade and Industries, and functions with success.

If, therefore, the settlement of such obligations, caused by the Czaristic war measures, occurs less rapidly than we wish, which gives the German government occasion for constant complaints, then this is not caused by the partial defects of our department alone (these defects are now eliminated), but by the fact that the Russian bourgeoisie strives to take advantage of our obligations to the Central Powers, and endeavors by all kinds of fictitious contracts to make demands upon us. The question of payments of interest on old loans, dividends, etc., cannot be separated from the question of interest obligations, caused by social legislation, and, likewise, cannot be separated from our duty to support our prisoners of war in Germany.

Our social legislation endeavors to unite the principal sources of the economic life of the country and place them in the hands of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Soviet. Many of these sources are in the hands of foreign subjects. If we nationalize these branches of industry, then we are compelled to compensate the German subjects for their losses. Our local Soviets do not always understand that the interests of the State of Workers and Peasants does not demand the indiscriminate confiscation of everything that happens to be there, but a suitable nationalization of such industries as are necessary for us, from the standpoint of the general economic plans of the state.

The indiscriminate nationalization of all possible kinds of moving picture houses and apothecary shops, requisition of foreign property without plan, without direct necessity, caused the State of Workers and Peasants to pay damages which run into hundreds of millions.

All such impracticable actions give cause for protest from the German government and also cause for conflicts which increase the obligations excessively. The question of computation of the damage caused by us, the question of the financial liquidation of our obligations which were caused by these actions and the question of the regulation of our social legislation relative to foreign subjects, demand immediate decision.

The joint Commission of German and Soviet representatives, who are at this moment is session in Berlin, is confronted by an extremely complicated problem. Our representative, Bronsky, proposed the following conditions for an agreement, in the name of the People’s Commisaire of Trade and Industry:

1. Russia must, for the sake of economic restoration, take up her eco- nomic relations with the Central Powers again, and at the same time continue her relations with the Entente Powers as far as possible.

2. To meet our obligations to the Central Powers, according to the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, we are compelled to conclude a loan, whereby the total amount of these obligations shall be turned into a state debt. The payments of interest shall be partly in products of our country, and timber, and partly in gold and in German securities in possession of the Russian government.

3. As a guarantee for this debt, and also for the payment of the more necessary products for the economic reconstruction of Russia now being bought in Germany, we propose to give certain concessions for the exploitation of natural resources in Russia. The condition of these concessions are within the existing Social and Trade laws of Russia and provide that we take part in the exploitation of these resources, retain a part of the proceeds and reserve the right of control.

4. The concessions cover the following branches of the State’s economy: (a) The production of oil. (b) The building of railroads. (c) The preparation and exploitation of certain branches of agriculture by introducing more scientific and technical methods of agriculture, under the condition that Germany will receive a certain part of the products resulting from such methods. (d) The production of artificial fertilizer. (e) The exploitation of the gold fields.

5. For the realization of these measures all the productive forces of Russia must be mobilized.

The following are the necessary conditions under which the agreement is sanctioned:

(a) No interference whatsoever by Germany in our internal politics. (b) No intervention by Germany in those countries with which she was formerly united, by the conclusion of mutual economic treaties, to wit: Ukraine, Poland, the Baltic Provinces (Estland) and the Caucasus.

(c) Recognition by Germany of the nationalization of foreign trade and the banks.

(d) Guarantee from Germany of the continuation of the supply of ore to Soviet Russia from Krivoi Rog in the Kherson government, and from the Caucasus, from which districts Russia has hitherto received at least half of the total ore production.

(e) Ratification of the boundary between Ukraine and the Don region whereby Russia shall be awarded the Donetz coal mines, as at present this boundary line runs through the center of the mines.

Concerning the demand that we meet our obligations by payment with products, we call attention to the fact that our decided refusal to agree with these claims does not mean that we refuse, for, as far as our position as neutral nation makes this possible to supply Germany with raw materials and products, we are willing to deliver to her what we can without injury to our own interests, without conflicting with the situation of our country as a neutral nation.

But our interests, the interests of an exhausted nation, make it necessary that we receive in return for products which are expensive in Europe at present such products as are absolutely necessary for the restoration of the country.

Relative to the opinions existing in the capitalistic centres of Germany, that our social experiments make the concessions worthless, that the nationalization excludes the possibility of making profits for foreign capitalists, we declare: Our country is in a state of deterioration; every other form of restoration, except the form which is pointed out by the German capitalists as a Socialistic experiment, would be resisted by strong opposition of the masses, as the people have learned by grave experience of many years. never to submit again to the uncontrolled capitalistic mix-up of restoration. If German Capitalism would reckon with this fact, and a fact it surely is then the German capitalistic centres would understand that we have, after the inevitable period of confusion, reached the work of organization, and that we require for this work the assistance of foreign economic apparatus, as long as we can not depend upon the assistance of a Socialistic Europe. We are prepared to pay for such assistance: yes, to pay. We declare it openly, as we are not to blame.

The nationalization of the principal branches of industry, the nationalization of foreign trade, do not exclude these payments; they but determine the form and manner of payment which foreign capital shall demand.

The question of the return of the prisoners of war and civil prisoners, and the maintenance of them until their return to their countries, played a great part in our relations to Germany and Austria-Hungary. Between Russia and Austria-Hungary, the question of the number of war prisoners to be transported presented no difficulties, as the number of prisoners on both sides was less than a million. There was difficulty with Germany, as the number of our war prisoners in Germany was more than a million, while the number of German prisoners in Russia was but little more than a hundred thousand. As the Russian-German commission in Moscow could not come to an agreement on this question of the basis for an exchange of war prisoners between Russia and Germany, it was referred to the Russian-German commission in Berlin, who adopted the principle of exchanging man for man, in accordance with an ultimatum of the German authorities on June 24. We had to accommodate ourselves to this demand. We are yet facing a severe struggle for the improvement of the conditions of our war prisoners in Germany, where the majority of them labor under extraordinary severe conditions. We must labor unceasingly so that when the German prisoners of war shall have returned to their country the future return of Russian prisoners occurs in the same period.

The relations with Austria-Hungary are less vital than those with Germany, as the treaty of Brest-Litovsk was only lately ratified by Austria-Hungary. In the beginning, there was only the question of the exchange of prisoners of war, but later a financial commission arrived in Moscow from Vienna, with the object of regulating the mutual financial obligations of both states upon a basis similar to that of the Russian-German commission in Berlin. Kameniev was appointed as our representative to Vienna. But we have not as yet received his recognition by the Austro-Hungarian government. We expect the appointment of representatives of Austria-Hungary to Moscow in the near future (this report was made in the beginning of July) which will greatly improve the relations between both countries.

The Turkish ambassador, Thalib-Kemal-Bey, came to Moscow with the German ambassador, Count Mirbach, but the establishment of friendly relations between the peoples of Russia and Turkey, which country is also the object of exploitation by World Capital, was prevented by the aggressive policy of Turkey in the Caucasus, where the Turkish army, after having occupied Batoum, Kars and Ardahan, commenced to advance further, oc- cupied Alexandropol and threatened Baku. The horrible treatment of the Mussulmen in the Caucasus was always pointed to by the Turkish ambassador as an answer to our protest.

The lately arrived Bulgarian ambassador, Mr. Tajaprasjnikof, pointed constantly to the absence of any cause that could interrupt the friendly relations of the peoples of Bulgaria and Russia, while at the same time, the total absence of all aggressive endeavors in our policy, to which we called the attention of the Bulgarian ambassador, makes it possible to maintain friendly relations in both countries.

The most favorable attitude to Soviet Russia among the Entente Powers was adopted by the United States of North America. (We remind our readers that this report was made in the beginning of July, 1918.) We want to remind you of the telegram of greetings to the Emergency Congress by President Wilson in March.

It is a public secret that at the moment when many voices were raised in favor of intervention by Japan in Siberia, the principal obstacle to intervention was the negative position of the government of the United States of North America. Our plan is to offer an economic agreement to the United States of North America, besides our negotiations for an agreement with Germany, and to Japan, as well, with which country, despite the landing of Japanese troops in Vladivostok and despite the campaign of a part of the Japanese press in favor of intervention, we hope to maintain friendly relations.

A great number of the French people adopted an unfriendly attitude towards Soviet Russia, caused by the annulment of the State debt. When the question of a possible armed invasion of Japan and may be of its allies in the Soviet domain became acute, the interview of the French ambassador in regard to the possibility of armed intervention, eventually even against the Soviet government, served as an alarming sign of a coming crisis. When the Russian government demanded the recall of the ambassador, whose declaration would prejudice the friendly relations of both countries, the French government gave no answer, and at this moment (beginning of July) the French ambassador is still present in Vologda, although the Russian government considers him merely an ordinary individual. On the other side, the French government refused to allow admission to France of Kamienev, who is traveling on a special mandate of the Russian government. Despite our continuous demands for the return of our troops stationed in France, only the invalids were sent home. Constant pressure was brought to bear in different ways upon our soldiers to induce them to continue the war in the ranks of the Russian legions. The great majority of the soldiers refused because they recognized the authority of the Soviet and approved the withdrawal of Russia from the war. On account of this, many were persecuted or were sent to the African penal camp.

In the beginning of the year (1918), when the negotiations concerning the return of our troops from France were started, France proposed, as an indispensable condition, the return of the Czecho-Slovak division to France, as France was very much concerned with their fate. When the Czecho- Slovaks started their rebellion, the representative of France in Moscow declared that the disarmament of the Czecho-Slovak soldiers would be considered as an unfriendly act of the Soviet government towards France. in which opinion he was supported by the representatives of England, Italy and the United States of North America.

The English government has, on the other hand, kept its frontiers. open to the agents of the Soviet government (this was, to remind the readers again, reported before the conspiracy of Lockhart, which caused the change in attitude of the English government) but also commenced negotiations with the authorized representative, Litvinof, of the Russian Soviet Republic. He was allowed the right to send and receive couriers, and to use the code, but notwithstanding this, the attitude of the English Government towards him is, in many respects, not in conformity with the dignity of the Russian Republic. After he had rented a house for the embassy of the Russian diplomats, the owner, without any cause, declared the contract void, and the court has evidently sustained the illegal action of the owner, the court embellishing its decision with comments which were offensive to the Soviet government. Our couriers were admitted but were subject to a careful investigation. When Kamienev and Zalkind arrived in England, all their diplomatic documents were taken away from them, and only returned when they left England. They were compelled to leave England at the first opportunity and the police who accompanied them treated them shamefully. A few people who were working in the bureau of our diplomatic staff were expelled from England, and were not even allowed to confer with Litvinof.

The English government maintains friendly relations with the old Czaristic embassy and consulate, as well as with the so-called Russian Governments and the English government consults them on all subjects which concern military service, Russian prisoners of war, Russian steamers in English harbors, and other general interests of Russia. Consul McLean in Glasgow and Simonof in Australia, appointed by Russia, were not recognized. The situation was most difficult right after the conclusion of the Brest-Litovsk treaty. The yellow press insulted McLean viciously.

The position of Russian citizens in England is, in general, very difficult; the pogrom agitation seems to continue in the newspapers. The return of Russian citizens is made very difficult for them. The old military agreement concluded by Kerensky, which gave the English government the right to draft Russian citizens in the English army, is still made use of. In the beginning of 1918, we declared to the government of Great Britain that we do not recognize this Kerensky agreement. Comrade Litvinof demanded the liberation of those citizens who were drafted into the English army upon the basis of this agreement, but received the answer that foreigners could not live in England without performing work in the interest of the nation and that those Russian citizens would be drafted in the workers’ division for the production of munitions for the army.

Soon after this many were transported into Egypt to be drafted in the Jewish legion in Palestine. The drafting of Russian citizens in the English army was temporarily discontinued, but afterwards renewed, with the difference that those who were called in the service were not put in the army in the field but in the above-mentioned workers’ division.

When, on April 5, a detachment of Japanese troops landed in Vladivostok, fifty English regiments also landed. A large section of the English press, particularly those controlled by the Northcliffe syndicate and the war industries, for a long time insisted upon further intervention by Japan in Siberia. Not only was this opposed by progressive elements in the labor movement, but also by a large number of liberals and even some of the far-sighted among the conservatives. The position of the government in regard to this question was not officially determined. The further course of the relations between Russia and England will be decided by England’s attitude toward intervention.

While Russia was in the war together with the Entente Powers, English war vessels were always at Murmansk. The Murmansk road played an extraordinarily important part in the military traffic between Russia and its Allies. After the conclusion of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, there departed by way of Murmansk for the west the military experts and emergency expeditions of the Allies formerly in Russia. This could not continue. Frequently we addressed the English representative with the demand that the war ships should be withdrawn from Murmansk. When the Murmansk situation became apparently a permanent relation of the present international position of Russia, the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs on June 14 demanded of England, France and the United States the withdrawal of their war ships Ten days after this demand the British landed 1100 men in Murmansk. Our answer to this armed invasion was to demand the withdrawal of the Allied troops, and to send our own troops to Murmansk. The agents of Great Britain explain the presence of English troops in Murmansk as an endeavor of the English government to protect this region against a German-Finnish advance. At a moment when the Entente powers declare their sympathy with the Czecho-Slovak divisions which are openly engaged in counter-revolutionary activity, it is a vital necessity for the Soviet Government to completely restore its power in Murmansk. We are now trying to accomplish this, and we hope for a favorable result.

It is the intention of Soviet Russia to arrive at an economic agreement with Germany and the United States for the exchange of products, and it is equally our intention to conclude a similar agreement with England. It depends entirely on England to utilize this opportunity. Among the ruling class of England there are elements endeavoring to establish friendly relations, and we have many friends among the working class of England. As the English government’s spokesmen in the labor movement refrain from expressions of friendship for Soviet Russia, we can find solace in the support of the as yet not powerful Socialist parties; the British Socialist Party constantly gives proof of, its enthusiastic solidarity with Soviet Russia, as well as the constantly developing movement of the spokesmen of the workers in the factories. This Shop-Stewards movement is a new expression of the independent mass movement of the workers of England, representing at this moment the most powerful and the most progressive factor in the English labor movement.

England, as well as Italy, the United States and France, participated in the declaration favoring the Czecho-Slovaks. Until this, the Italian representatives had always emphasized the friendly attitude of Italy toward our people.

The unfortunate people of Serbia are, on account of their general conditions, much more inclined to show its solidarity with the heavily-burdened proletariat of Russia. Contrary to this was the attitude of the official representatives of Serbia, who were always under the influence of the policy of the Entente Powers.

Our relations with the Rumanian Government must not be confused with our relations with the Rumanian people, among whom the Russian Revolution had already begun to make inroads in the South when the revolutionary movement was violently stopped. At this moment our relations with the Rumanian Government are not settled. The annexation of Bessarabia to Rumania was accomplished through a fictitious right of self-de- termination by a small group of the population and accompanied by unparalleled violence.

Concerning the neutral powers, Sweden protected the interests of the German subjects, Denmark those of Austria-Hungary. The questions concerning the German and Austrian prisoners of war were always a subject of very animated discussion between ourselves and Sweden and Denmark.

We intended to establish economic relations with the three Scandinavian states. The interests of our citizens, and thus of our prisoners in Germany, were taken care of by Spain, but the Spanish Government adopted an extremely reticent attitude toward Soviet Russia. The Spanish Embassy has delivered only the keys of our Embassy in Berlin to the German Government, but it refused to deliver to us the administration of our prisoners of war. The Spanish Government also refused to allow our citizens to leave Spain. The Swiss Government, after acknowledging our authorized representative, Comrade Bersine, did not immediately admit his staff and his couriers are always meeting difficulties in their travels to the Swiss Republic. Our relations to all these states, and the foreign states in general, affect the existence of our Worker’s and Peasants’ Dictatorship. Our inroads on the rights of private property are of great influence. Insofar as these inroads are legal in method, under the power to tax, the foreigners are subject to our measures. Insofar as irregularities occur which do not come within the scope of our regulated economic policy, the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs has always exercised its influence upon the local Soviets to regulate the situation of the foreigners; and at this moment instructions are being worked out in conformity with all the other People’s Commissaires. Nevertheless, we inform the foreign Governments that our social reforms cannot end at the door steps of those who consider themselves foreign subjects.

Our policy in the Eastern countries is determined by the peace measure adopted at the All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers, Soldiers and Peasants, November 7, 1917.

Imperialism has created in the East a special kind of veiled annexations. This is the so-called right of European Concessions and Capitulations, which determines that citizens of imperialistic countries are subject to the administrative powers and not the local laws. The imperialistic governments have been relying upon their armed power to coerce these Oriental countries, consisting partly of their own troops and partly of native elements ambitious for conquest. These governments have pursued in the Oriental countries a policy which places their subjects and their interests in extraordinarily favorable circumstances, to the disadvantage of the native peoples. They have established settlements, within which the natives are slaves, and within which they are sometimes not even allowed to live. They have by their absolute independence of the native government protected themselves, created an impregnable citadel from which they gradually extend their power over the oppressed people of the East.

Socialist Russia cannot reconcile itself with such a situation, despite its existence for centuries. Socialist Russia, since the November Revolution, has declared to the Oriental peoples that it is not only willing to abandon with the Rumanian Government are not settled. The annexation of Bessarabia to Rumania was accomplished through a fictitious right of self-determination by a small group of the population and accompanied by unparalleled violence.

Concerning the neutral powers, Sweden protected the interests of the German subjects, Denmark those of Austria-Hungary. The questions concerning the German and Austrian prisoners of war were always a subject of very animated discussion between ourselves and Sweden and Denmark.

We intended to establish economic relations with the three Scandinavian states. The interests of our citizens, and thus of our prisoners in Germany, were taken care of by Spain, but the Spanish Government adopted an extremely reticent attitude toward Soviet Russia. The Spanish Embassy has delivered only the keys of our Embassy in Berlin to the German Government, but it refused to deliver to us the administration of our prisoners of war. The Spanish Government also refused to allow our citizens to leave Spain. The Swiss Government, after acknowledging our authorized representative, Comrade Bersine, did not immediately admit his staff and his couriers are always meeting difficulties in their travels to the Swiss Republic. Our relations to all these states, and the foreign states in general, affect the existence of our Worker’s and Peasants’ Dictatorship. Our inroads on the rights of private property are of great influence. Insofar as these inroads are legal in method, under the power to tax, the foreigners are subject to our measures. Insofar as irregularities occur which do not come within the scope of our regulated economic policy, the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs has always exercised its influence upon the local Soviets to regulate the situation of the foreigners; and at this moment instructions are being worked out in conformity with all the other People’s Commissaires. Nevertheless, we inform the foreign Governments that our social reforms cannot end at the door steps of those who consider themselves foreign subjects.

Our policy in the Eastern countries is determined by the peace measure adopted at the All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers, Soldiers and Peasants, November 7, 1917.

Imperialism has created in the East a special kind of veiled annexations. This is the so-called right of European Concessions and Capitulations, which determines that citizens of imperialistic countries are subject to the administrative powers and not the local laws. The imperialistic governments have been relying upon their armed power to coerce these Oriental countries, consisting partly of their own troops and partly of native elements ambitious for conquest. These governments have pursued in the Oriental countries a policy which places their subjects and their interests in extraordinarily favorable circumstances, to the disadvantage of the native peoples. They have established settlements, within which the natives are slaves, and within which they are sometimes not even allowed to live. They have by their absolute independence of the native government protected themselves, created an impregnable citadel from which they gradually extend their power over the oppressed people of the East.

Socialist Russia cannot reconcile itself with such a situation, despite its existence for centuries. Socialist Russia, since the November Revolution, has declared to the Oriental peoples that it is not only willing to abandon war, this open declaration was presented to us and to the whole democratic world by the representatives of revolutionary China.

You may realize what impression the Russian Revolution created upon the Capitalistic Governments. In February, 1918, an uprising of the proletarian masses in Tokio took place, an uprising which was immediately sup- pressed by the Japanese Government. Five of the most prominent representatives of the lately organized Social-Democratic Party were arrested. The war censor suppressed carefully all reports from Russia.

Revolutionary Siberia is in danger of foreign intervention. On April 5 the Japanese troops landed in Vladivostok and remained there uninterrupted. And yet there begins in Japan slowly but surely the struggle for the right of self-determination of the people. And this struggle is especially noticeable in the question of interference in Russian affairs. The man who is the representative of the dying but still powerful feudal regime in Japan, Count Motono, former ambassador in Russia and who was closely connected with the Russian reactionaries in hiding in Japan. was compelled to resign. At present a struggle is going on in Japan between the representatives of the reactionary military party, who endeavor by all means to provoke a conflict with the Russian people, and to utilize our weakness for their own advantage. and the representatives of the more moderate liberal opinion who desire certain advantages in a peaceful manner, without making an enemy of Russia, as they know very well, that the encroachment of Japan in Russian affairs would determine our mutual relations and possibly the whole further history of the Far East for the immediate future.

We are prepared to assist to a great extent Japanese citizens who wish to develop the natural resources of Siberia in a peaceful way, and to low them to take part in our industrial and business life. We are willing in case China gives her consent, to relinquish some of our rights in the East-Siberian railway and to grant Japan the Southern branch of this rail- road, and to extend to Japan other advantages by the importation of Japanese products to Russia. We are willing to renew with Japan the trade treaty and the fishing agreement, which agreement was always a source of prosperity for the people of Japan, because the Russian fish is not only the principal food of the Japanese but also serves as fertilizer for the rice-fields. We have communicated this to the Japanese Government, and we have started with this Government unofficial discussions. The people of Japan must know this and must know the value of these concessions. concessions which even as other things which happen in Russia are kept secret for these people, as for instance the fact that Russia would extend the hand of friendship to the people of Japan and offers to establish mutual relations with these people upon a healthy and permanent basis. The people must know, that if they refuse to grasp the hand of friendship, the responsibility rests upon those classes in Japan who in the interest of their own greediness have kept these things secret for the people of Japan. If the destiny of history should bring forth that Japan, misguided and blinded, would decide upon the insane step of trying to strangle the Russian Revolution then the working classes of Russia will arise as one for the protection of that which is most cherished and valuable to them namely: the protection of the results of the Social Revolution.

CONCLUSION

As we now review our whole international policy of the last 4 months, we must acknowledge that Soviet Russia stands as an alien among the capitalistic governments of the world. These governments conduct themselves in general in regards to Soviet Russia, in such a way as to make any other attitude impossible. The condition of Soviet Russia, that in regards to the imperialistic coalitions stands between two fires, is extraordinarily difficult. We can say, however, with absolute assurance, that the best, yes the only way to extricate ourselves from this situation is: our internal strengthening, the development of our internal life upon the basis of the Soviet policy, our economic restoration upon the basis of communist production, restoration of our defensive powers for the protection of the results of our Revolution. The more this is accomplished the better will be our situation from without. Our foreign policy depends upon our domestic policy.

The Proletarian Revolution in Russia by N. Lenin and Leon Trotzky with Louis C Fraina. Communist Press Publishers, New York City. October, 1918.

A truly unique historic document and (486 page) collection of Lenin and Trotsky, writings from the first year of the Revolution with additions by Chicherin and Fraina. Personally edited, introduced, produced, and published by pioneering US Communist Louis C. Fraina in New York City in October, 1918.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.158284/2015.158284.The-Proletarian-Revolution-In-Russia_text.pdf