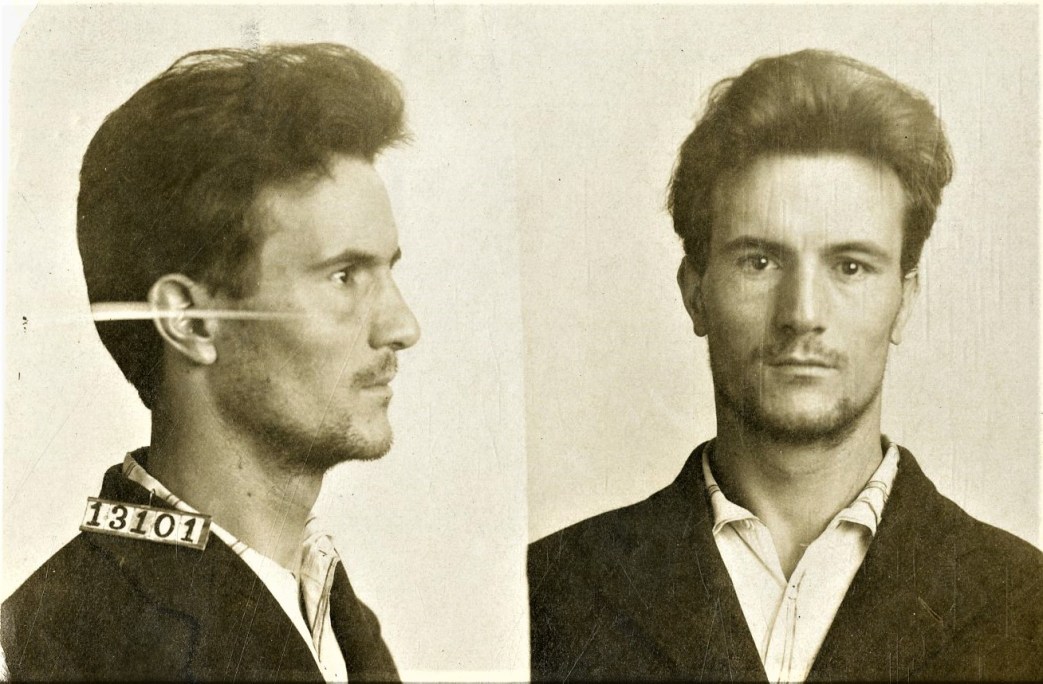

Pride, community, dignity, and power. George Andreytchine, himself radicalized in Minnesota’s great iron strike, relates the profound changes the union and its struggle brought to the workers of the Mesaba Range.

‘How the I.W.W. Has Transformed the Mesaba Range’ by George Andreytchine from Solidarity. Vol. 8 No. 370. February 10, 1917.

Hibbing, Minn. A few lines to let you know what is going on around the Mesaba Range I have no words to describe the difference between the Range I lived in and the one I found upon my return. The air has changed so pure and healthful-no skunks around to stink. The miners look so plucky, free, and their manhood is so apparent,

Only ten months ago one needed only to come here to realize without difficulty how the lower strata of humanity was choking all noble passions and ideas that may spring up in the hearts of the oppressed miners. The bosses, from superintendent to pencil pushers, all obedient watchdogs, were the accursed enemies of freedom and expression. To revolt against them meant starvation and suffering in the severe winters of the Mesaba range.

Now the workers freely boast of the strength of the union, and are challenging the murderous steel trust with a clenched fist of 15,000 rough hands. Warm blood flows through my veins at the sight of every miner who boldly greets you with “Fellow Worker”–the nightmare of the steel trust. I have seen hundreds of them already, and not one scab has been shown to me yet

The Duluth New Spittoon says that as far as the Mesaba Range is concerned the I.W.W. is a dead issue. Hold on, you skunk! (That is the name they give that dirty sheet in every home, school and police station on the Range. Last night the kind Hibbing police expressed openly their contempt for that perfidious liar.)

I visited Virginia, Kitzville, Chisholm, and Hibbing. Every miner you meet on the street hails you cordially.

Last night, after posting 200 bills advertising the meeting of Sunday, Jan. 28, I went to see Fellow Worker Ettor at the Oliver Hotel. Peter Wring, a famous gunman and a very obedient servant of the steel trust, came and insolently said he had orders “pick me up.” We asked for a warrant; he said it was at the police station. We went there and there was none. Then he said was it at Virginia. Phoned over there; nothing doing. He confessed to Ettor and Carl Tjiel, the photographer, that he thought there was a warrant once in Virginia. He is a plain liar.

The superintendent of the Oliver Iron Mining Co., Wm. J. West, the very same gentle and mild Christian who said at the beginning of the strike last summer that it would have been much better to have me shot like a dog, and there would have been no strike, heard that I was in town and that I was going to speak Sunday and challenge them by putting on the bill. “Is the I.W.W. dead?” He ordered his tool, Peter Wring, to come and arrest me in order to stop me from speaking at the meeting. Til now here has been no warrant shown and I expect that Judge Hughes will dismiss the case altogether, or that I will be released on bail. I intend to sue Peter Wring for false arrest and imprisonment. The man has shown himself one of the most devoted watchdogs the steel interests around Hibbing, and there is no man that has any use for him except the Oliver Co.

He was very badly mistaken about the enthusiasm of the miners’ having been killed. They came about a hundred of them to see me at the police station while I was in the chief’s office all Sunday. The interest and bold statements of the miners amaze me. Some of them said that these outrages must stop, or we are going to stop them ourselves. Fellow Workers Ettor and Bartoletti brought me a gorgeous Italian dinner and many of the boys sacks of fruit. I bet that Billy West did not like it very well.

One thing is apparent from the questions asked by some of ex-fellow workers of the Oliver that the steel trust is in deadly fear of another strike. First question was asked by a superintendent, whether we intend to pull another strike next spring. The I.W.W. is dead, says the Duluth Spittoon. Come here d see for yourself. The steel trust has spies everywhere in the hotels and restaurants and by the blacklist system they are trying to exterminate us. Nothing doing! The more they hate us, the more the workers like us, and the faster we grow. There are few mines that cannot tolerate scabs at all. And the treatment the miners get from the straw bosses and others is not to be compared with that they got before. Their pay has increased about 6 per cent. No charge for tools. The powder used to be charged at the rate of $9 and $10; now in some mines it is less than $5, some $5.50 and $6, and it must be remembered that the price of powder has gone up 25 per cent. since last August. The contract has been done away with in a few mines already and in places the miners are getting all that is coming to them under this stem. The bosses say: “Boys, keep track of your output; Whatever you say, is coming to you, get.” And they do. The Oliver even, that used to reduce pay from $10 to $3.10 and $2.90. openly says that if you make $10 and even more, you will get it.

The boys ask the captains what made the companies so kind-hearted? Well, the price of ore has gone up, and on account of the high cost of living, too! Oh, my! say the wobblies. We know! The union gets da goods!

A few days ago a superintendent asked one of the boys, “Are you an I.W.W.?” “Yes,” was the bold answer, “I can guess you are; you work so slow.” “Well, Super, if you don’t like it, why don’t you show us how to do it?” He was not so anxious to comply as he used to be before. I know that mean soul. He used to take the shovels from the boys and scare them by working like a damned fool for a few seconds and then say, “Work like that; if you don’t, get to hell out of here.” But now he was compelled to see one Wob sit down and smoke a “pill” and then say to the super: “You are a home-made slave; go on like that, you do it better than I.”

Once this slave superintendent said that if you don’t like it, to the get to hell away from it. Now it is our turn to say to him the likes of him: “If you don’t like the I.W.W., get to hell off our Range.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1917/v8-w370-feb-10-1917-solidarity.pdf