Longuet writes a history of French socialism in the universities starting around 1880, with a focus on the “Groupe des Etudiants Socialistes Revolutionnaires” founded in 1891 at Paris University, for a journal of Socialist college students in the U.S.

‘The Socialist Movement Among the Students of French Universities’ by Jean Longuet from The Intercollegiate Socialist. Vol. 2 No. 3. February-March, 1914.

Socialism has never been in French universities the dominating power it has been for many years in darkest Russia, where nearly all the young intellectual fighters for political liberty are at the same time convinced adherents of the economic freedom of the masses. But France is certainly one of the countries of Europe where the “intellectuals” of the universities, and more especially of the great Paris Université, have played a great part in the Socialist movement.

Without going back to the remote times of the great Utopian Socialists, at the beginning and in the middle of the last century, when St. Simon and Fourier found their first disciples and propagandists among the students of the high Polytechnique School for artillery officers and state engineers, in Paris; nor to the end of the Second Empire, when a vague Socialistic feeling–more especially inspired by Proudhon–was mixed up with the militant republicanism of the “Quartier Latin,”1 we find in 1878-1880, at the beginning of the modern Socialist movement in France, a small Socialist group among Paris University students. To that circle belong Gabriel Deville, Massard and several others who were associated with Jules Guesde when he created at that time the first Parti Ouvrier.

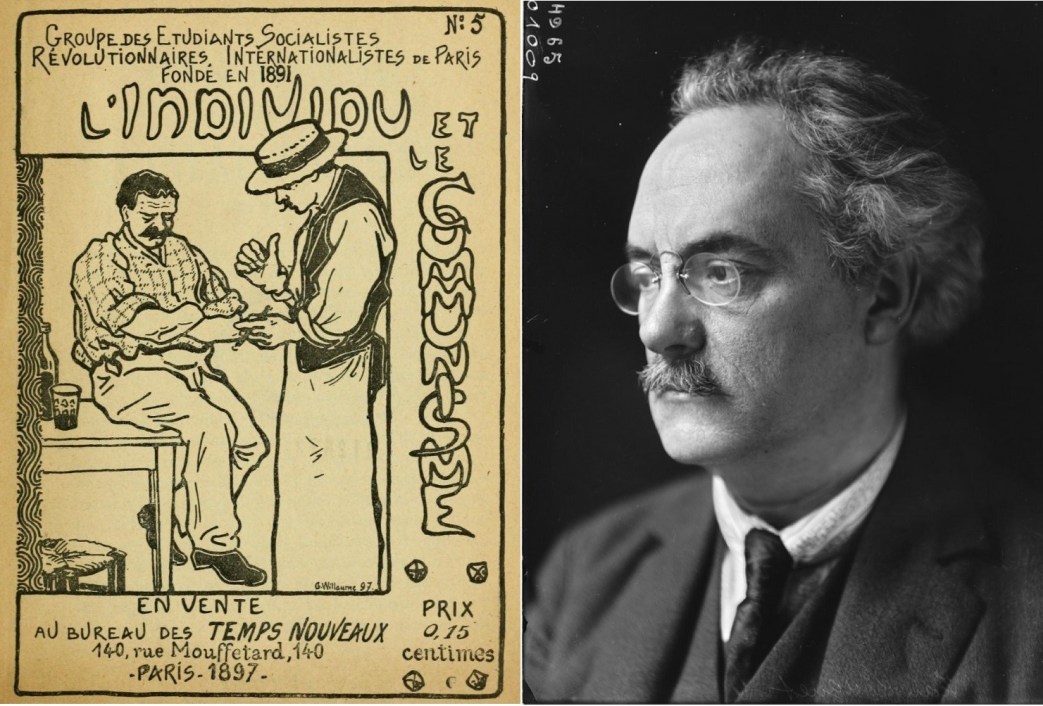

But we must wait till 1891-1893, when Socialism appears for the first time as an important factor of French political life, with a parliamentary force of 25 to 30 members in the Chamber of Deputies, to see the growth of a serious movement among the students of the Paris University. It was in 1891 that an organization was started which was called the “Groupe des Etudiants Socialistes Revolutionnaires Internationalistes de Paris,” by a few young enthusiasts, students in the Law and Medical faculties, and also in the old” Sorbonne” renowned for literary, historical and scientific faculties. Among those who created this first group, several have since become opponents of the party under the mask of so-called “independent Socialists”; one of them, a certain Zenais, is even now one of the most contemptible enemies of our movement, and recently published a book full of shameless insults against our much regretted Paul Lafargue. But the others have remained in the movement and are still active. This first group had a rather vague basis. French Socialism was then–as it remained till 1905–divided between five conflicting sections, and under the pretext of not taking sides with either, the group was open to all sorts of erratic people, more specially of the anarchistic tendency, who, after a certain time, obtained a strong influence over it, which led to its decadence and disappearance. Because of this influence, two years later a few members of this first group seceded and created the “Groupe des Etudiants Collectivistes de Paris,” in March, 1893, that soon became, after several eclipses and a change in its title, the great center of Socialist life and activity among the students of Paris University and higher colleges. This group exists to the present day.

The “Groupe des Etudiants Collectivistes” affiliated immediately with the “Guesdist” section of French Socialism, the one which was supposed to be nearer to the teachings and methods of Marx.

From the beginning, we find French Socialist students influenced powerfully by Marxism. While of all Socialist movements on the Continent of Europe French Socialism has unfortunately been least imbued with the teachings of Karl Marx, its students’ movement has been Marxian in all its sections. The “Etudiants Socialistes Revolutionnaires Internationalistes” (the first group), in its evolution towards anarchistic tendencies and toward what has been since called Syndicalism, was always anxious to show that it was developing Marx’s doctrines, and the “Etudiants Collectivistes” began by a serious study of the economic and historical basis of Marxian Socialism. It has certainly been one of the things it can most proudly boast of, that all those who have been members of this club during the nineties and since have seriously learned what modern Socialism is. At the same time the “Collectivist Students” were from the beginning unsectarian, in favor of Socialist unity in this country, and were rapidly aligned on this question in opposition to the more sectarian and narrow element which constituted the Guesdist party with whom they were affiliated.

They were at the same time bitterly opposed to the “adventurers,” the “politicians” (in the bad sense of the word it has in French) who come into the movement for personal profit. Young, convinced and enthusiastic Socialists, these students were annoyed to be classed with Zenais who was, by the way, one of the society’s founders. So that one of the first big events in the life of the Club was the expulsion in 1894 of this man, Zenais. The latter, however, most unfortunately, remained for ten years more an active member of the Guesdist party, was elected as one of its representatives in the French Parliament in 1898, and betrayed it in 1903.

Consisting as they did of sincere and honest elements, the “Collectivist Students” made great progress. They had but from 25 to 40 members. Each new university year brought new adherents, but at the same time took away old members, who left the University to practise as lawyers, professors, physicians, or journalists. But nearly all were militant members, who took a deep interest not only in the group’s life, but in the general life of the French and the international Socialist movements.

The influence of this small group was marked. Every month they arranged large meetings, addressed by Jaures, the great French Socialist orator; Vandervelde, the renowned Belgian Socialist leader; Gabriel Deville, then with Guesde and Lafargue, the most renowned French representatives of Marxism; Enrico Ferri, the Italian leader; Rouanet, the representative of Benoit Malon’s teachings; Louis de Brouckere, the Belgian; Van Koll, the Holland Socialist leader and others. These scientific lectures were held in the large hall of the Hotel des Societés Savantes, and were regularly attended by from 1,000 to 2,000. Students of the various faculties and militant members of working class Socialist clubs were also in attendance at these big meetings.

At the beginning of each year the groups which had now become the only center of Socialist life in the Latin Quarter (the honest, but Utopian little club of the “Revolutionnaires Internationalistes” having disappeared in 1892-1899), launched eloquent manifestoes in all Paris faculties and high colleges, appealing “not to the interests of the students as such, but to their brains and hearts.” At the same time the students were told that “they should not expect to enter the movement as leaders, for the working class had to lead itself, but as comrades in the great world-wide movement for Socialism.” During the Dreyfus Affair, when all the essential liberties of modern democracy were threatened in France by the aggression of militarism, Catholic clericalism and antisemitism, the Collectivist Students’ Club made great progress. Many students of advanced views, although not conscious Socialists, joined it, and its numbers reached from 150 to 200. This alliance was short-lived, however, and after the liberal bourgeoisie had defeated reaction with the help of the working class, it forgot entirely its proletarian allies, and in the Latin Quarter the students’ movement reached its lowest level.

Meanwhile the more active members of the Club who were becoming prominent members of the Party, took an active part in the first attempt made from December, 1899, to August, 1900, to create Socialist unity in France, and began the publication, in 1899, of “The Mouvement Socialiste,” a very useful fortnightly scientific Socialist review. At the same time, however, nearly all of the militant members of the group were losing contact with the Latin Quarter, and from 1905 to 1908 we find little activity in the Latin Quarter, and a sleepy little club.

In the latter year, however, a new and vigorous movement again sprang up. The members decided to give to the reorganized club the name of “Groupe des Etudiants Socialistes Revolutionnaires.” This organization is at present very active, consisting of one hundred members belonging to all the big Paris colleges and faculties, the big “Ecole Normale Superienne,” the “Sorbonne,” the “Ecole de Droit” (law school), the “Faculté de Medecine,” etc. It has also created a Socialist School.

In the provinces, several universities. have had Socialist Students’ Clubs. Similar clubs have existed for many years in Lyons, in Nancy, in Montpellier, where there was a strong Russian and Bulgarian contingent, as well as in Toulouse. The Socialist Students’ Club in the last named city has given to the Paris Collectivist Club some of its most prominent and active members.

It must naturally be borne in mind by those organizing Socialist clubs among intellectuals in the universities that a very large percentage of the young students who come to Socialism when they are 20 years old will leave. the movement later when they will have obtained “respectable” positions in society. This is an unavoidable fact. At the same time a certain proportion will remain in the movement and play an important part in the Socialist Party which always needs “intellectuals.” Our experience in France has taught us that a strong and active organization of students in the universities can bring a large number of students to Socialism, and equip them with a thorough understanding of our doctrines such as will keep them in the movement and make them most useful members of the party.

While the ordinary percentage of former students who have remained Socialists is perhaps less than 20 or 24 per cent, we can boast that 70 or 80 per cent of the former members of the Paris Collectivist Students are at present militant workers in the Party and are among those who have the best Socialist and Marxian culture.

In the French Parliament, at present, we have among our 70 members at least ten who have been members of the Club, among them Comrade Brignet, a lawyer; Aubriot, an “employe”; Barthe, a chemist; Brizon, a professor; De la Porte, a professor; Roblin, a lawyer; Lagresiliere, a lawyer; Ohivnèr, a physician.

Among the members of the Central Executive Committee of the Party, four, among them the writer of this article, are former members of the Club. In the Party’s central paper, L’Humanité, the general manager, Landrieu, (a chemist), is a former member of the Club, as are also some of the chief contributors, among them Morizet, originator of a vigorous campaign against political “boodlers”; Uhry, a court and tribunal reporter; the present writer, a foreign editor. The general secretary of the Socialist Co-operative Federation, E. Poisson, is also one of those who have learned their Socialism in our Latin Quarter “milieu.” “milieu.” The Paris municipal councillor, Dormoy, is still another. Among the thirty members of the Socialist Association of the Paris Bar, 18 are former members of the Club.

Naturally, at the same time, among those who are in the capitalist parties are men like Zenais, of whom I have already spoken; like M. Breton, who left the Party three years ago to become an “independent” Socialist in Parliament; like M. Emile Buié, who is now a high government official, and M. Anatole de Monzie, the “orator” in 1900 of our club, and later an under-minister for the commercial fleet in the cabinet of M. Barthou. But we must strongly insist on this point that these are exceptions, although the people who don’t like Socialist intellectuals either outside or inside the Party, always speak of these few exceptions as the rule, while ignoring the fact that the overwhelming majority are loyal Socialists. At any rate, those in France connected for the last 15 or 18 years with the Socialist movement in the universities have acquired much valuable experience.

At the occasion of the Vienna International Congress next August, it would be, we think, a special advantage to hold a meeting of representatives of Socialist students and former Socialist students of all the big universities of Europe and America, and discuss these experiences for the common benefit of the whole movement. Already the British students have urged such a conference. We hope it will be realized.

Jean Longuet has long been active in the French Socialist movement. He was a member of the French Socialist Party Executive from 1895 to 1906, and one of the most active members of the Paris University Socialist Students’ Club.

1. Such was, for instance, the case of the first fighting republican paper, “La Rive Gauche,” originated in 1856 in the “Quartier Latin” by my father, Charles Longuet, and later with Rochefort’s “Marseillaise.”

The Socialist Review was the organ of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, and replaced The Intercollegiate Socialist magazine in 1919. The society, founded in 1905, was non-aligned but in the orbit of the Socialist Party and had an office for several years at the Rand School. It published the Intercollegiate Socialist monthly and The Socialist Review from 1919. Both journals are largely theoretically, but cover a range of topics wider than most of the party press of the time. At first dedicated to promoting socialism on campus, graduates, and among college alumni, the Society grew into the League for Industrial Democracy as it moved towards workers education. The Socialist Review became Labor Age in 1921.

PDF of full issue: https://books.google.com/books/download/The_Intercollegiate_Socialist.pdf?id=YMMZAAAAIAAJ&output=pdf