Charles Ashleigh on the ‘Everett Massacre’ of November 5, 1916 in which hundreds of armed thugs attempted to prevent the landing of I.W.W. activists from Seattle onboard the Verona as it docked in Everett. The I.W.W. defended itself. Two gunthugs were killed and two dozen wounded at least five wobblies died, potentially a dozen more drowned, and another thirty were wounded.

‘Everett’s Bloody Sunday’ by Charles Ashleigh from the Masses. Vol. 9 No. 4. February, 1917.

THERE had been a strike of Longshoremen on the Pacific Coast and a strike of Shingle Weavers in Everett, Washington. With the assistance of strike breakers the employers were in a position of vantage to defeat both strikes and contribute towards the Open Shop policy on the coast which they were pledged to support. But the strikers also had their assistants, “Fellow Workers” in Seattle, members of the I.W.W. who believe that a strike of any workers in any industry is the concern of every other worker.

For many weeks before “Bloody Sunday” Everett had not been what you could call a pleasant loitering place for working men. To the Commercial Club in Everett, a man in overalls, perhaps just off his job with his pay in his pocket was a subject for deportation from the town. A longshoreman, named Johnson, had been in jail for many weeks without a charge against him. He was held incommunicado and beaten daily with a rubber hose. The rubber hose had special advantages applied to an I.W.W. man; it inflicted injury without leaving surface marks for detection. It was before Johnson was arrested that the photographs of the welts and bruises of Fellow Worker James Rowan had been printed and circulated. Rowan had been deported from Everett because he was an organizer. But Rowan was not a coward and he came back. At a meeting he read an extract from the report of the Federal Commission on Industrial Relations. “You can’t talk that sort of stuff here,” an intelligent policeman shouted. “Get out.” He was put into an automobile, driven into the country and beaten into unconsciousness.

But there were citizens of Everett who resented the activities of the Commercial Club and its disciples, the “lawnorder men.” They encouraged the I.W.W. men of Seattle to push their labor agitation for the sake of the rights of free speech. It was that encouragement that took 41 men to Everett, October 30th, with the intention of holding a meeting the same afternoon. They went by boat and as they landed they were received at the dock by a mob with heavy saps; they were loaded into automobiles and driven to Beverly Park, a lonely wooded piece of ground on the outskirts of the town. Another mob received them at the Park. One by one the boys were turned out of the machines. As they were forced to run the gauntlet of the “lawnorder men” a shower of heavy blows fell on their heads and across their bodies. The air rang with curses for labor unions. Torn clothing, bloodstained hats and bloodstained cattle guards along the railroad tracks bore the evidence of the mob law for many visitors who sought the place for evidence the following day.

The workers, with the naiveté of people who believe in the righteousness of their cause, believed that the outrage against them and what they stood for, had aroused the indignation of the people in Everett and that this sentiment should be used without delay to re-establish the right of workers to walk the streets of the town and speak without interference. They immediately planned the second expedition and gave it wide publicity, showing their faith in the protection of public sentiment. For the same reason the meeting was planned for Sunday and in the daylight when the streets of the town would be filled with people.

Two hundred and fifty working men volunteered for this second expedition, each man in the party purchased his passage ticket on either the Steamer “Verona” or “Calista.” The crowd was enthusiastic because it believed that the trip would win, re-win for the workers of Everett the common rights of citizenship. It may still do that, but the sight they saw from their steamer, the “Verona,” in its arrival was not reassuring. The pier was filled by the Sheriff and his deputies and out in the water was another tug offensively manned and on another pier further along were more armed men.

The prosecuting attorney stated later that not more than 25 men out of the 250 carried weapons and the Mayor of Seattle later said, “If I had been one of the party of I.W.W.’s almost beaten to death by 300 Everett citizens without being able to defend myself, I probably would have armed myself if I had intended to visit Everett again.” But the men on the piers and in the tug were fully armed. The entire stock of ammunition in the hardware stores of the town had been exhausted and a rifle was in the hand of every member of the posse the Sheriff had formed.

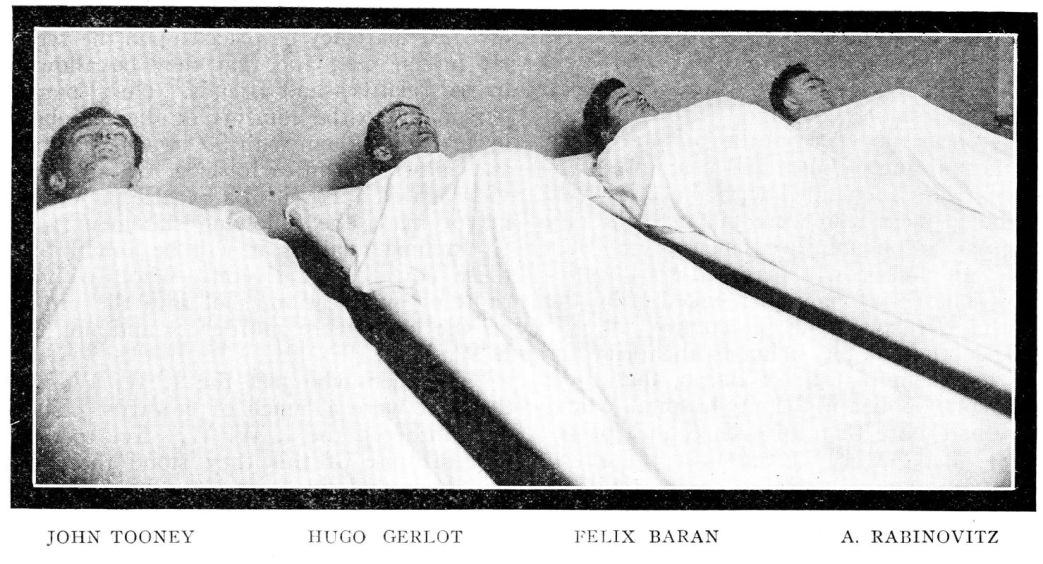

As the boat drew into the dock the Sheriff shouted, “You can’t land here. Who is the leader?” “We are all leaders,” was the answer of the men seeking freedom. The sheriff’s hand went to his gun. Five of the I.W.W. men were killed and over thirty were wounded.

Two deputies were killed and fifteen wounded.

Is it really important who fired the first shot? The supposition of the sympathizers with the men on the boat is that the Sheriff did. But does it matter? Suppose the first shot did come from the boat, it was the Sheriff’s preemption of the pier and his belligerent gesture as the men answered his question that makes him, in the eyes of Mayor Gill of Seattle, the murderer.

“In the final analysis,” the mayor declared, “it will be found these cowards in Everett who, without right or justification, shot into the crowd on the boat were the murderers and not the I.W.W.’s.

“The men who met the I.W.W.’s at the boat were a bunch of cowards. They outnumbered the I.W.W.’s five to one, and in spite of this they stood there on the dock and fired into the boat, I.W.W.’s innocent passengers and all.

“McRae and his deputies had no legal right to tell the I.W.W.’s or anyone else that they could not land there. When the sheriff put his hand on the butt of his gun and told them they could not land, he fired the first shot, in the eyes of the law, and the I.W.W.’s can claim that they shot in self-defense.”

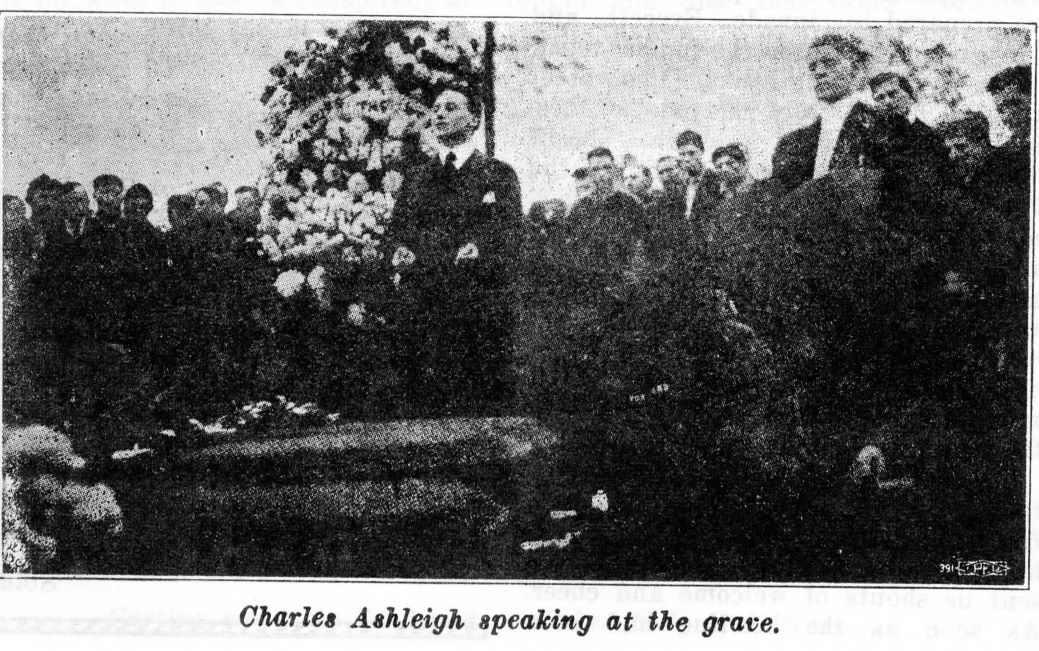

When the “Verona,” with its dead and wounded men on board, and the “Calista,” which had turned about before it reached Everett, landed at Seattle, they were met by the police and militia and taken to the County Jail. There are now in the Jail–one hundred–awaiting trial. Defending one hundred men is a damned hard job. But we have got to do it. THE MASSES can help. It can tell its readers to send all their spare cash to The Everett Prisoners’ Defense Committee, Box 1878, Seattle, Washington. CHARLES ASHLEIGH.

The Masses was among the most important, and best, radical journals of 20th century America. It was started in 1911 as an illustrated socialist monthly by Dutch immigrant Piet Vlag, who shortly left the magazine. It was then edited by Max Eastman who wrote in his first editorial: “A Free Magazine — This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers — There is a field for this publication in America. Help us to find it.” The Masses successfully combined arts and politics and was the voice of urban, cosmopolitan, liberatory socialism. It became the leading anti-war voice in the run-up to World War One and helped to popularize industrial unions and support of workers strikes. It was sexually and culturally emancipatory, which placed it both politically and socially and odds the leadership of the Socialist Party, which also found support in its pages. The art, art criticism, and literature it featured was all imbued with its, increasing, radicalism. Floyd Dell was it literature editor and saw to the publication of important works and writers. Its radicalism and anti-war stance brought Federal charges against its editors for attempting to disrupt conscription during World War One which closed the paper in 1917. The editors returned in early 1918 with the adopted the name of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, which continued the interest in culture and the arts as well as the aesthetic of The Masses/ Contributors to this essential publication of the US left included: Sherwood Anderson, Cornelia Barns, George Bellows, Louise Bryant, Arthur B. Davies, Dorothy Day, Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, Wanda Gag, Jack London, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Inez Milholland, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Carl Sandburg, John French Sloan, Upton Sinclair, Louis Untermeyer, Mary Heaton Vorse, and Art Young.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/masses/issues/tamiment/t70-v09n04-m68-feb-1917.pdf