By her own admission, no individual of the Russian Revolution was as impressive to Louise Bryant as the terrorist Maria Spiridonova.

‘Maria Spiridonova: Woman Leader of the People’s Army’ by Louise Bryant from Truth (Duluth). Vol. 2 No. 18. May 3, 1918.

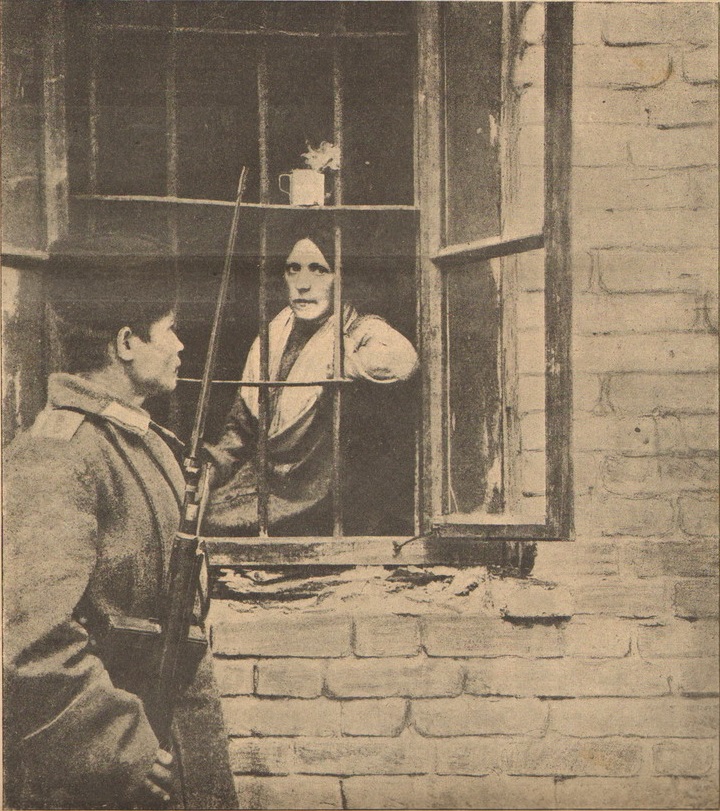

Maria Spiridonova looks as if she came from New England. Her puritanical plain black clothes with the chaste little white collars, and a certain air of refinement and severity about her seem to belong to that region more than to mad, turbulent Russin–yet she is a true daughter of Russia and of the revolution.

She is very young, just past 30 -and appears exceedingly frail–but she has the wiry, unbreakable strength of many so-called “delicate people,” and she has great powers of recuperation.

Her history as a revolutionist stands out even in the minds of the Russians who are used to great injustices.

“Oh! Spiridonova,” they will say. “Yes, she is one of our greatest martyrs.”

Then they will tell you this story:

She was 19 when she killed Lupjenovsky, Governor of Tambov. Lupjenovsky had as dark a record as any official ever possessed. He went from village to village taking an insane, diabolical delight in torturing people.

When peasants were unable to pay their taxes or offended him in any way at all, he made them stand in line many hours in the cold and ordered them publicly flogged.

He arrested anyone who dared to say that he held a different political view from his own.

He invited the Cossacks to all sorts of outrages against the peasants, especially against the women.

Spiridonova was a student in Tambov. She was not poor and she suffered no personal discomfort, but she could not bear the misery about her. She decided to kill Lupjenovsky.

Shoots Governor Through Heart.

One afternoon she met him in the railway station. The first shot she fired over his head to clear the crowd; the next she aimed straight at his heart, and Spiridonova has steady hand as well as a clear head.

Lupjenovsky was surrounded by Cossacks at the time. They arrested Maria Spiridonova. They acted in as hideous a performance as ever occurred.

First the Cossacks beat her and threw her into a cold cell quite naked. Later they came back and commanded her to the names of all her comrades and accomplices. Spiridonova refused to speak, so she had bunches of her long, beautiful hair pulled out and she was burned all over with cigarettes.

For two nights she was passed around among the Cossacks and the gendarmes.

But there is an end to all things; Spiridonova fell violently ill. When they passed her death sentence she knew nothing at all about it, and when they changed it to life imprisonment she did not know.

They sent her out to Siberia in a half-conscious condition. None of her friends ever expected to see her again.

When the February revolution broke out eleven years later she came back from Siberia, ready again to offer her life for freedom.

Worshiped by the Masses.

It is hard for us in comfortable America to understand the fervor of people like Spiridonova. It is a great pity that we do not understand it, because it is so fine and unselfish.

I once asked her how she managed to keep her mind clear during all the eleven years that she was in Siberia. “I learned languages,” she said. “You see, it is purely a mechanical business and therefore a wonderful soother of nerves. It is like a game and one gets deeply interested. That is how I learned English and French.”

No other woman in Russia has quite the worship from the masses of the people as Spiridonova.

She was elected president of both the All-Russian congresses held in Petrograd within the last six months, and she swayed those congresses largely to her will.

At the present time she is chairman of the executive committee of the peasants’ soviets and she is an influential leader in the Left Social Revolutionist party.

Soldiers and sailors address her as “dear comrade” instead of just ordinary “tavaritele.”

The first time I saw Spiridonova was at the Democratic Congress.

Orators had been on the platform arguing about a coalition for hours. A hush fell over the place when she walked out on the stage.

She spoke for not more than three minutes, giving a short, concise, clear argument against coalition. The audience roared when she ceased and cried, “Bravo! Bravo!”

In the same way that she can stir up hearers she can also keep them down.

“Greatest Woman in Russia.”

I have seen her keep down the radicals when a conservative speech was made that she wanted spoken for one reason or another sometimes because she wanted to smash it when it was finished. She will stand exactly like a bandmaster, swinging her arms behind the speaker in gestures you are sure mean, “Put on the soft pedal.”

If she were not such a clear thinker and so inspired a person her leadership of the physical giants would be ludicrous, Spiridonova is barely five feet tall. She may weigh 100 pounds, and she may weigh less. She has big gray eyes circled with blue rings and soft brown hair, which she wears in a coronet braid. She works on an average of about sixteen hours a day, and everybody in Russia pours into her office at 6 Fontanka to ask advice. I used to go there and sit and watch her and she would tell me interesting stories.

One day I took in a Russian girl who belonged to the Menshevik party and who, therefore, was opposed to Spiridonova. She sat silent and listened to her for two, hours. When we came out on the street the girl stopped and her eyes were full of tears.

“To think,” she said, “that with such eyes and such a face she should ever kill a man! Always until I saw her I was opposed to her, but now I know she is the greatest woman in Russia!”

I believe that, too, and I have great respect for Mme. Kollontai, the Bolshevik Minister of Welfare; for Countess Panina, whom Lenine speaks of as “one of the cleverest defenders of the capitalist class”; for “Babushka,” Mme. Stahl, who manages the violent Cronstadt sailors, and for many others.

The last time I saw Spiridonova she talked to me about the war and the possibility of a decent peace being secured at Brest-Litovsk. She did not have any faith in the success of the negotiations, and she was seriously working on the organization of what she called a Socialist army.” “We have made secret inquiries,” she went on, “and we know we will have enough men; they will all be volunteers; there must be no compulsion.”

She spoke sadly of the sabotagers, especially of the intellectuals. “They consider the Russian revolution an adventure and they hold aloof, but the Russian revolution is much more than that, even if it fails for the present.

“It is the beginning of social revolution all over the world; it is social revolution here in full swing.

The whole country is taking part in it now. My reports come in from the remotest districts. The peasants are very conscious and are making social changes everywhere.

Calls Women More Conscientious Than Men.

We talked about women and I wanted to know why more of them did not take public office since there is absolute equality now and no one thinks it is strange at all for women to do anything that men do.

In Russia today, more than ever, the refreshing attitude of the whole nation is to let everyone do, act and say what he pleases, Spiridonova smiled at my question.

“I am afraid I am a bit of a feminist,” she confessed. “I will tell you my theory about it. You will remember before the revolution as many women as men were sent to Siberia and exiled. Some years there were even more. Now that was all a very different matter. It needed no particular training to be a martyr. Political careers are another thing–not at all so fine.

“I think women are more conscientious than men. Men accept political positions with readiness, whether they are sure they can fill them or not. They are used to doing it and so it does not appear strange to them.”

Sees in Spiridonova Joan of Arc of Russia.

I remembered something Angelica Balabanov once said when we were discussing the same thing. “Women,” she said, “have to go through a tremendous struggle before they are free at all, so that they take their freedom very seriously because they sacrifice so many precious things to obtain it.”

When the Bolsheviki came into power they took over the famous old land program of the Social Revolutionists. This brought about great turmoil in that party. The Right maintained that it was their program and no one had the right to steal it, but Spiridonova and all her wing only laughed.

“What difference does it make,” she wanted to know, “who gives the peasants their land–the principal thing is that they get it.” This was one of the reasons that the Social Revolutionists split and the great left wing joined the Bolsheviki.

The left Social Revolutionists are the only party in Russia who rise above party and, personally, I have more admiration for them than any party in Russia. They are bound to play a large part when the first wildness of the revolution begins to settle down, because they are a reasonable, intellectual party, led by some of the purest idealists of all Russia.

I was not at all surprised today when I read they had decided not to accept the disgraceful German demands, no matter what other party signs them.

The Kaiser will have a colossal task to subdue their unconquerable spirits. I would not be surprised. either, if Spiridonova should become the Joan of Arc of Russia, leading her soldiers to battle as well as through the dif- ideals. [sic]

Message to America:

“Try to understand us.” The day I left Russia, Spiridonova gave me her picture. She hates publicity and has stubbornly refused to have a photograph taken. This one she took off her passport. When she was signing her name on the back she looked up and said:

“Never mind saying anything good about me, but do say something about the revolution. Try to make them understand in great America how hard we over here are striving to maintain our ideals.”

Truth emerged from the The Duluth Labor Leader, a weekly English language publication of the Scandinavian local of the Socialist Party in Duluth, Minnesota and began on May Day, 1917 as a Left Wing alternative to the Duluth Labor World. The paper was aligned to both the SP and the I.W.W. leading to the paper being closed down in the first big anti-I.W.W. raids in September, 1917. The paper was reborn as Truth, with the Duluth Scandinavian Socialists joining the Communist Labor Party of America in 1919. Shortly after the editor, Jack Carney, was arrested and convicted of espionage in 1920. Truth continued to publish with a new editor J.O. Bentall until 1923 as an unofficial paper of the C.P.

PDF of full issue: https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn89081142/1918-05-03/ed-1/seq-2