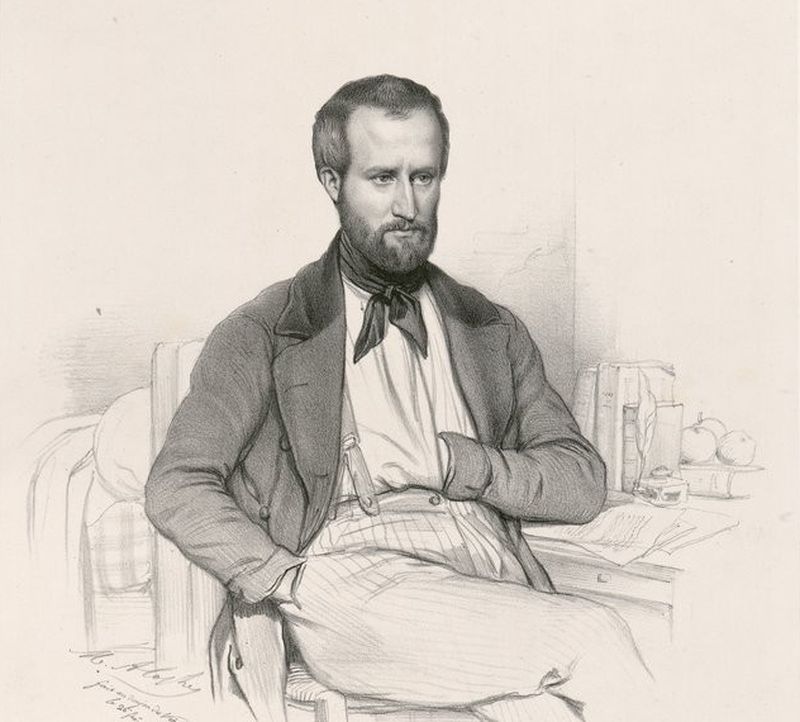

Paul Frölich reflects on the life and legacy of the ‘Master of Conspiracy’ on the fiftieth anniversary of his death.

‘Auguste Blanqui: The Eternal Prisoner’ by Paul Frölich from Revolutionary Age (Communist Party–Majority Group). Vol. 2 No. 8. January 24, 1931.

Fifty years ago, on January 1st, 1881 there died in Paris the greatest leader of the revolutionary French proletariat, Auguste Blanqui. Struggle and prison–these two words describe his entire life. Three times was he wounded in street fighting. Twice was he condemned to death. Half of his life did he spend in the prison cell.

The Master of Conspiracy

At the age of 19, in the year 1824 he joined a democratic conspiratorial group. He worked among the revolutionary youth, took part in demonstrations and barricade struggles and in 1829 went to prison for the first time. The July revolution of 1830 saw him again on the barricades. The new bourgeois kingdom and the rule of high finance found a bitter enemy in him. He belonged to the vanguard of the republicans, was involved in various conspiracies and in 1832 was sent to prison for a year. At the end of his term he became the disciple and friend of the old Buonarotti, the comrade-in-arms of Babeuf. Thus did he take up the great traditions of the “Equals” and thus was he won for the ideas of Communism. In 1835 Blanqui joined the secret “Society of the Families” and became one of its leaders, alongside of Barbes. In 1836 he was sentenced to three years imprisonment because of the possession of explosives. In 1837 his sentence was commuted. In the same year he formed the “Society of the Seasons” a conspiratorial organization which was preparing an insurrection. This insurrection was initiated on May 12, 1839 but it failed, since the masses of the people of Paris did not rally in support of the storm troops. In 1840 Blanqui was condemned to death; again the sentence commuted, this time to life imprisonment. Four terrible years passed. Blanqui was practically at the point of death when the February, Revolution of 1848 freed him.

In the 1848 Revolution

The Republican Central Society, as the Blanqui club was known, became the focal point of revolutionary agitation and Blanqui himself became the embodiment of the will and fighting power of the Paris proletariat. Marx definitely declared the identity of his own leading ideas with those. of Blanqui in the 1848 revolution:

“The proletariat grouped itself more and more around revolutionary socialism, around Communism, for which the bourgeois itself found the name of Blanqui” (Class Struggle in France)

Only a few months of freedom were vouchsafed to Blanqui. He took part in great demonstrations against the attempts of the bourgeoisie to reap all the gains of the revolution. Against his own will, since he saw that the time was not yet ripe, he was involved in an attempt to disperse the reactionary National Assembly. In the June struggles, the tragic high point of the revolution, he was no longer able to take part, for at the end of May he was already arrested. In April 1849 he was condemned to ten years in prison for high treason. For ten years he was dragged from one jail to another. After his term was over, he was exiled to Africa. It was only in 1859 that he saw freedom again.

After a short residence in London he came back to Paris illegally in order to take up the struggle against Bonapartism. In secret, printing houses, leaflets, and pamphlets were prepared; the threads of a secret organization were gathered together again. At the funeral of the 48’er Caussidiere he was betrayed, arrested and condemned to four years in prison. From the depths of his cell he created a new party organization. In 1865 he succeeded in escaping. The First International had just been created. But Blanqui forbade his supporters to join it because it did not exclude the Proudhonists. He welded together a fighting organization out of groups of ten–so that finally it included 2,500 men.

The Paris Commune and After

At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war and with the first defeat of the French it appeared that the time for action had come. On August 14, 1870, three weeks before the time was really ripe, the Blanquists broke loose. But again the blow failed; again the workers did not follow. And on September 4, when the revolution really broke out, the Blanquists were disorganized and not in the position to play the role they should have. After Napoleon’s fall Blanqui assured the new government of his support on the condition that it would ensure the republic and carry on the struggle against the foreign enemy with determination.

His paper, La Patrie en Danger (The Fatherland in Danger) carried on a vigorous struggle in this direction. But it soon because obvious that the new government was more afraid of a revolution than of the Prussians and Blanqui reopened the struggle against the betrayal of country and class. On October 31, after the shameful capitulation of Metz, the National Guard arose in insurrection. For a few hours the government was overthrown, a central committee with the full powers of government set up in which Blanqui was a member. But the insurrection collapsed and Blanqui went into hiding again. On March 9, 1871, he was condemned to death in his absence. Deprived of all means and seriously sick Blanqui sought safety in the south of France. On March 17 one day before the outbreak of the Commune, he was discovered and arrested.

The prisoner was elected into the Commune. The Commune offered to the Versailles all hostages with the Archbishop at the head in exchange for Blanqui alone. But Thiers knew the value of the man; he refused to give up the “vipers head”. Again he was sent to some far off fortress. After the collapse of the Commune he was sentenced to deportation–because of “moral participation” in the Commune. In June, 1879 he was freed by amnesty. For a year and a half he continued vigorous propaganda for his ideas. On January 1, 1881 he died suddenly of a heart attack.

The Historical Significance of Blanqui

Blanqui was the outstanding representative of revolutionary action in the France of 1830-1871. It was the period in which the leadership of the revolution was passed from the petty bourgeoisie to the proletariat with both classes still participating in the leadership. In Blanqui’s world of thought this transition was reflected. He is the connecting link between the Jacobins and Babeuf and Karl Marx. He hated the exploiters and oppressors with a bitter hatred, but his social-economic ideas were very primitive. As did the Jacobins so did Blanqui overestimate the creative power of force. But precisely for this reason did he have a deep insight into the necessity of a period in which force would play the decisive role, the period after the seizure of power by the revolutionary class, therefore, he preached the dictatorship of the proletariat, the essential points of which were very clear to him.

“All governments will be traitors”, he declared in a famous appeal of 1851, “which, raised to power by the proletariat, will not immediately carry thru: (1) the disarming of the bourgeois guards, (2) the arming of all workers and their organizations as a national militia. No weapons must remain in the hands of the bourgeoisie…Arms and organization, these are the decisive elements of progress, the means by which a decisive end can be put to misery. Who has iron has bread.”

Blanqui was the John the Baptist the modern labor movement. It was his misfortune that he could never participate in the high tide of revolutionary struggle. It was his fate that he always made the attempt at the decisive blow too early and in this way endangered the revolution. The strategy of this precursor of Marxism is incomplete. He believed that the heroic act of an organized vanguard would tear the masses to insurrection and thereby assure the victory of the working class. He preceded the masses not by one step as Lenin required but always by at least ten. He therefore remained isolated from the masses and all he achieved was a putsch. This weak point of his strategy was conditioned by the period in which he lived in which the chief role was still played by the petty bourgeoisie, organizable with the greatest difficulty, while, the proletariat could not yet build any mass movement. Lack of experience and the absence of prerequisites were at the root of Blanqui’s errors. When these errors are repeated today they become crimes.

Marx and Lenin have led us beyond Blanqui. But against reformism Blanqui is still today a champion who must be saved from oblivion and studied with zeal. The man, the fighter, the martyr of the proletariat must remain for us a splendid example.

Workers Age was the continuation of Revolutionary Age, begun in 1929 and published in New York City by the Communist Party U.S.A. Majority Group, lead by Jay Lovestone and Ben Gitlow and aligned with Bukharin in the Soviet Union and the International Communist (Right) Opposition in the Communist International. Workers Age was a weekly published between 1932 and 1941. Writers and or editors for Workers Age included Lovestone, Gitlow, Will Herberg, Lyman Fraser, Geogre F. Miles, Bertram D. Wolfe, Charles S. Zimmerman, Lewis Corey (Louis Fraina), Albert Bell, William Kruse, Jack Rubenstein, Harry Winitsky, Jack MacDonald, Bert Miller, and Ben Davidson. During the run of Workers Age, the ‘Lovestonites’ name changed from Communist Party (Majority Group) (November 1929-September 1932) to the Communist Party of the USA (Opposition) (September 1932-May 1937) to the Independent Communist Labor League (May 1937-July 1938) to the Independent Labor League of America (July 1938-January 1941), and often referred to simply as ‘CPO’ (Communist Party Opposition). While those interested in the history of Lovestone and the ‘Right Opposition’ will find the paper essential, students of the labor movement of the 1930s will find a wealth of information in its pages as well. Though small in size, the CPO plaid a leading role in a number of important unions, particularly in industry dominated by Jewish and Yiddish-speaking labor, particularly with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Local 22, the International Fur & Leather Workers Union, the Doll and Toy Workers Union, and the United Shoe and Leather Workers Union, as well as having influence in the New York Teachers, United Autoworkers, and others.

For a PDF of the full issue