A look at the science, technology, and political economy behind the development of FM radio and why we still use both.

‘From AM to FM’ by Mark B. Clark from New Masses. Vol. 38 No. 7. February 4, 1941.

Frequency modulation, radio’s new wonder child. How it came about. Are the new receivers worth buying? The big broadcasting chains have a headache.

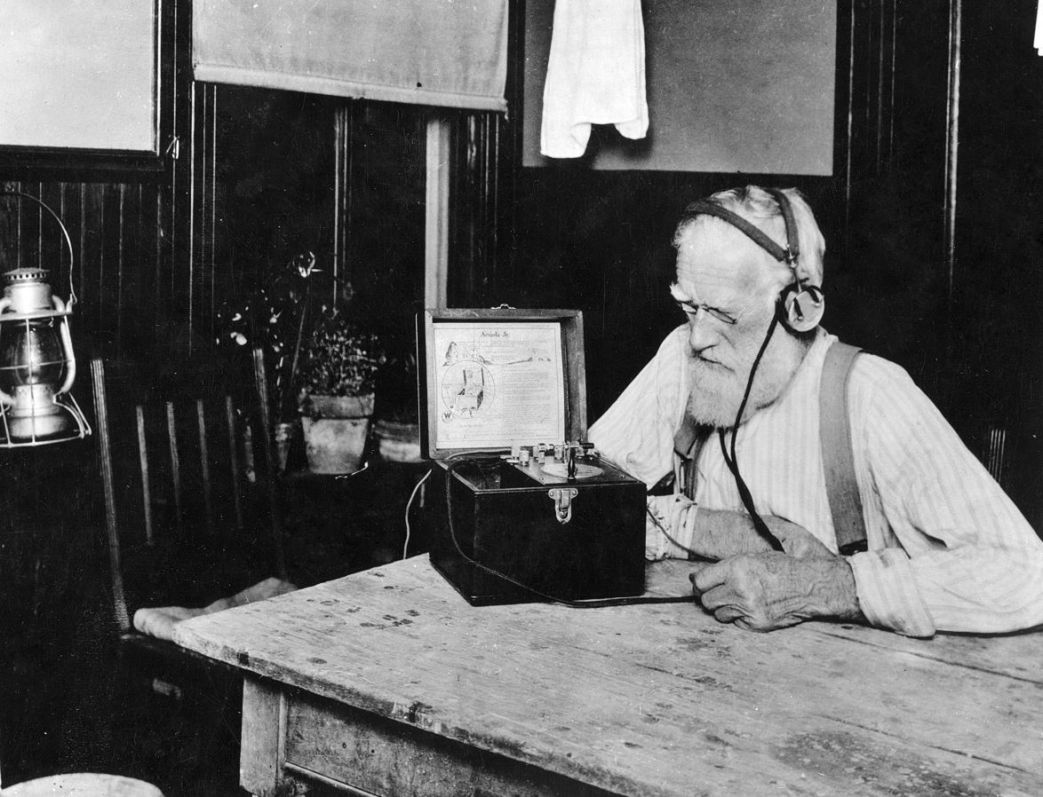

WITHIN the past year, there have been new development in radio called FM. The letters stand for frequency modulation as distinct from the system now in use, AM or amplitude modulation. The newspaper articles promise that FM will correct all of the technical defects of radio reception and that it will soon be possible to hear Superman as though he were in the same room as the listeners.

The promoters of FM advance two claims for their method which should give it great superiority over AM: 1. Reduction of extraneous noise, such as the hissing caused by the tubes themselves, interference caused by electric razors, elevators, and neon lights; 2. Faithful tone reproduction. Only the first claim is justified. Faithful tone reproduction is independent of the type of modulation in- volved. Today, if one is willing to pay the price, there are high fidelity receivers on the market for AM which give excellent reproduction. An equivalent type of receiver will be necessary to get the full benefit of FM.

The word frequency means the measure of electric vibrations. For example, the current generated in power houses for general use is called sixty-cycle alternating current. This means that the current reverses itself sixty times a second. In radio use, the number of vibrations per second, or frequency, runs into the thousands of cycles, called kilocycles. WJZ in New York, for example, transmits on 760,000 cycles, or 760 kilocycles. In FM transmission, the frequencies run still higher, into the millions of cycles, or megacycles. Television broadcast bands are even higher.

AMPLITUDE MODULATION

The word amplitude refers to the intensity of the vibration. The louder a signal, the greater its amplitude. The measure of amplitude for an electric wave is volts. Radio reception, however, depends upon frequency, and so the words cycle, kilocycle, and mega-cycle will appear throughout this article.

The first difficulty radio engineers met in the pioneer days was the fact that a radio signal reproducing sound at its own frequency was absorbed by the air, and could only be sent over a distance of a few feet. If the audible range of sound frequencies, which extends from about sixteen cycles up to 20,000 cycles a second, were converted into electric vibrations, they could be sent only over very short distances. Soon after, however, it was discovered that frequencies of the order of hundreds of kilocycles would not only penetrate the atmosphere, but actually follow the curvature of the earth.

The next forward step was to use the penetrating high frequencies to carry the audible low frequencies along with them. It was done this way: the high frequency wave, called the carrier is generated with a constant amplitude. The signal to be transmitted is superimposed on the carrier in such a way that the amplitude of the carrier varies with the frequency of the signal. For example, a tuning fork striking a C causes a vibration of 259 cycles. When this sound is transmitted over the radio, the carrier has its amplitude changed 259 times a second.

The signal travels through the atmosphere, then, as a high frequency wave of varying amplitude, and it is picked up by the receiver in the same form. The receiver is so constructed that only the variations of the carrier amplitude are allowed to reach the loudspeaker, and so one hears only the original signal. To tune in in the New York area one sets his radio for one particular carrier frequency, 760 kilocycles for WJZ and 860 for WABC.

This is the present system, amplitude modulation, so-called because the original signal modifies the carrier amplitude. Carrier frequencies are allotted by the Federal Communications Commission in such a way that no two stations operating in the same region at the same time have the same carrier. The FCC also decides what power output a station may have, thus controlling the size of the area it can reach.

Frequency modulation also uses a carrier, but now the frequency of the carrier is varied with the frequency of the signal. The tuning fork can be used as an example again. If we look at the carrier, we will find that its frequency is varying at the rate of 259 times each second. If the tuning fork is made louder, the amount that the carrier frequency changes will increase, but still at the rate of 259 times a second.

The FM receivers permit only the rate of carrier frequency variation to reach the loud-carrier frequency variation to reach the loud- speaker: therefore FM and AM receivers are radically different in construction, and one cannot receive the signals meant for the other. Since most static is amplitude modulation, FM sets do not respond to it, and this accounts for their relative freedom from noise. Similarly, FM reception is not affected by steel structures or passing cars.

The range of audible frequencies, as given before, is between fifteen and twenty kilocycles, and every radio carrier must therefore control the frequencies on either side of it to carry through an AM signal. Thus, the standard broadcast bands are allowed five kilocycles on either side, 765 to 755 for WJZ. This is only ten kilocycles, and the higher part of the audible range cannot be heard. Ten kilocycles are sufficient to pass the average speaking voice, but not the higher over-tones which give color and tone to music.

Even though most AM transmitters have a frequency range of ten kilocycles, most receivers are tuned only for a range of about six or seven kilocycles, cutting reproduction even more. High fidelity sets are tuned over the entire ten kilocycle range, but they are priced far above the average sets.

HIGH FREQUENCY

FM works only at frequencies much higher than those of the standard carriers, running into millions of cycles (megacycles) rather than thousands. The FCC places them up in the region from 43 megacycles to 50 megacycles. This permits them to have sidebands of the order of 200 kilocycles wide which is sufficient. to transmit a wave that could give almost perfect reproduction. The drawback is that the ordinary receivers are not tuned to take advantage of it.

It is pointed out that a carrier frequency of 700 kilocycles will follow the curvature of the earth, and AM signals can travel around the world. Still higher frequencies, such as those used by FM, while not absorbed by the atmosphere, do not follow the earth’s surface, but actually penetrate the outer atmosphere and leave the earth at the horizon. This means that an FM station can reach an area only about seventy miles in radius. To reach a larger area, it will have to be picked up and rebroadcast. The advantage of this is that only a relatively small number of carrier frequencies need be used as long as no two stations in the same broadcasting region have the same one.

It should be repeated that all the advantages accruing from the use of very high frequencies are not necessarily due to FM, but could be obtained also for AM. The drawback to AM in that frequency range is that AM signals would still be subject to noise and static. A system has already been worked out for FM stations by the FCC to fix the number of stations in an area by the size of the population. In an area under 500 square miles, the number of stations will be three, provided the population is under 25,000. For greater populations, the number of stations can go up to eleven for an area of 3,000 square miles.

The present form of FM was developed by Major Edwin H. Armstrong, who has a licensing arrangement with the manufacturers. Armstrong made a fortune out of his super-heterodyne. At present, Radio Corporation of America, General Electric, Philco, Stromberg-Carlson, Lafayette, and a half dozen others are marketing FM receivers and converters. These converters, which look just like a complete radio set, receive FM broad- casts and then convert them into AM. At this point the signal is fed into your present AM set where it is amplified and converted into sound through your loudspeaker. Besides taking up the extra space, the converter has the drawback that your present receiver is probably not tuned to take advantage of the frequency range to give the good reproduction available.

The great advantage of FM lies in the fact that portable units can receive signals very clearly in spite of steel obstructions, cables, bridges, power lines, etc. Portable transmission units are also extremely efficient, and should be superior to AM outfits because the conditions under which they are manipulated are those where natural interference would be greatest, and FM is unaffected by it. It is rumored that German tanks are serviced with FM sets for local communication, and one of the popular radio magazines suggests that the American army will follow suit.

A bulletin of Consumers Union (August 1940) says: “The fidelity of the converter-radio combination is limited by the fidelity of the amplifier and speaker in most sets, relatively poor. Nevertheless, noise reduction and some improvement may be expected.”

So much for the ABC of frequency modulation broadcasting. On the social side, FM offers a revealing case history in the economics of modern business subdivision: monopoly and science. For FM is a cogent example of a remarkable invention, a definite advance over an existing technical system, which big business would prefer to hold back–or better still, bury–because it threatens its lushly lucrative stranglehold on an important industry.

THE HIGH-POWER STATIONS

The really big money in broadcasting is reaped by the high power stations–the standard radio band allows for only sixty-eight 50,000-watt stations-and by NBC and Columbia which own, lease, or have affiliations with virtually all the existing 50-kilowatt outlets. Radio stations, of course, make money by selling time on the air, a peculiar form of natural resource which is theirs to exploit gratis in “…the public interest, convenience, and necessity”-and corporate profit. They were lucky enough to fall into these exclusive gold mines in the early days of the business, and now they are piling up the proceeds. The price for which stations can sell this air is determined, in the final analysis, not by the programs they pump into the vacant ether–since the building of commercial programs has passed almost exclusively into the hands of the advertising agencies–but to their power. A powerful station reaches more people firmly and clearly, hits more potential customers for the advertiser.

Take the city of Detroit, for instance, which the ad boys call “a rich market.” WJBK, only 250 watts, charges $93.75 an hour. WXYZ is 5,000 watts and has an hourly rate of $375. And WJR, one of the fortunate 50,000-watters, can sell its time for $700 an hour! Or consider Pittsburgh where the 250-watt WWSW asks $125 an hour, the 1,000-watt KQV $250, and the 50,000- watt KDKA $500.

Because they do not want to change this pleasantly profitable situation, NBC, Columbia, and the high-power stations have not, and are not actively encouraging the development of frequency modulation. They fear the future. If FM were to become the dominant system of broadcasting, they would lose much of the advantage that is now theirs-power could not be the dollars-and-cents yardstick. All FM stations in a given region are licensed to serve the same fixed area. All FM stations in New York, for instance, will have a coverage area of 8,500 square miles each, and no one broadcaster will have an edge over the other because of power. Moreover, if FM were to become the major means of transmission, since FM technically can allow hundreds more stations than can be fitted into the AM band, there would be much more competition in the broadcasting business-another potential which the loud voices fear.

Major Armstrong had the assistance of RCA in his experiments during 1933-34. A recent Saturday Evening Post article on FM stated: “In April 1935, after almost a year of tests, RCA told Armstrong it needed the transmitter for television–he would have to go. Armstrong packed up bitterly. He contends that RCA never meant to give FM a real chance. RCA officials were frightened by FM’s implications, he charges, and ‘tried to discourage me.”

Nevertheless, despite the opposition of RCA, which controls NBC, and of CBS and their satellites, FM seems likely to develop rapidly, because of the internal conflicts within the broadcasting industry. First of all, the lower-powered stations see an opportunity to get in on something which may eventually put them on a par with the now dominant high-power stations. It is significant that one of the pioneer promoters of FM, along with Major Armstrong himself, has been an astute gentleman by the name of John Shepard III, who controls the Yankee & Colonial network in New England, which owns four stations and has eighteen others affiliated. Mr. Shepard makes a lot of money, but he’d like to make makes a lot of money, but he’d like to make more. He has no 50,000-watt outlets to help him realize that goal. So he has plumped hard for properly placed FM stations, with which he could blanket New England–and more–as thoroughly and as profitably as if he owned a string of 50,000-watters.

FM TRANSMITTERS

Another factor accelerating the development of FM is the situation in the radio manufacturing industry. As a whole, set producers welcome the advent of FM. They see in it an opportunity to build a market again for higher priced sets. Today, the vast majority of receiver sales are in the low-priced midget class. The manufacturers relish a chance to get away from nine-dollar radios with small margins of profit to the big combinations selling for over $100, where the real money is. As the demand for FM sets rises, these manufacturers will increase their pressure on the FM stations for better program service.

Also pushing hard for frequency modulation are those frustrated businessmen who have been weeping for the last decade that they “should have gone into the broadcasting game years ago when I had the chance.” They think this may be another big chance–the chance to get in on radio’s second “ground floor.” And the FCC is fostering these might- have-beens by a policy of encouraging grants of FM licenses to newcomers to broadcasting.

Meanwhile, the fat boys of the kilocycles are not entirely asleep. The FCC regulations provide that no one owner can have more than three FM stations, and the big net- works already have their bids in for their commercial FM outlets.

At present, there are only a few FM transmitters in the New York region, and these give rebroadcasts of the major networks. W2XOR at 43.5 megacycles gives WOR and Mutual programs from 9 AM until midnight. W2XQR at 43.2 megacycles is on from 5 to 11 PM with WQXR programs, and W2XWG gives the NBC programs from 3 to 11 PM at 45.1 megacycles. W2XMN, on 42.5 mega- cycles, broadcasts the recorded music of “Muzak,” the wired music company, from 4 PM to 11 PM daily.

To date the FCC has already issued construction permits for FM stations in Baton Rouge, Detroit, Schenectady, Milwaukee, Los Angeles, Chicago, Nashville, Salt Lake City, Hartford, Pittsburgh, Boston, Columbus, O., Evansville, Ind., Binghamton, N.Y. These new stations will probably be on the air from within six months to a year. If you live out- side of metropolitan New York or outside the broadcast range of these other cities your FM set or converter will be a fine dust- catcher for the next few years (although the FCC is expected to grant several dozen more FM licenses during 1941, and your city may be included among those in which such stations may be established). If you live inside the region where FM stations are now, or will soon be, broadcasting, you might give FM some consideration, your pocketbook per- mitting. On the other hand, if you can’t take a hint, and you simply must have one, then Consumers Union says:

“CU can make no general recommendation on buying a new receiver until sufficient models are available for test…Combination FM-AM radios will cost more than standard receivers, and FM radios alone will be somewhat more expensive than AM…particularly when they incorporate a high fidelity audio system converters will sell any- where between $50 and $100.”

Until the situation clears somewhat, it is the writer’s opinion that if you’ve put up with AM for so long, you can hold out a little longer. AM transmission of commercial broadcasts is here to stay for a good number of years. The most optimistic guesses are it will be five years before fifty percent of the radios sold will be capable of FM reception.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

For PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1941/v38n07-feb-04-1941-NM.pdf