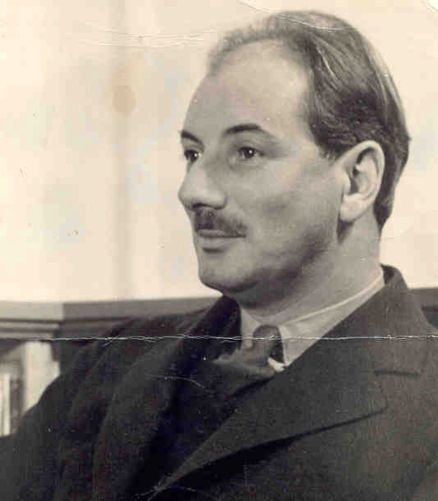

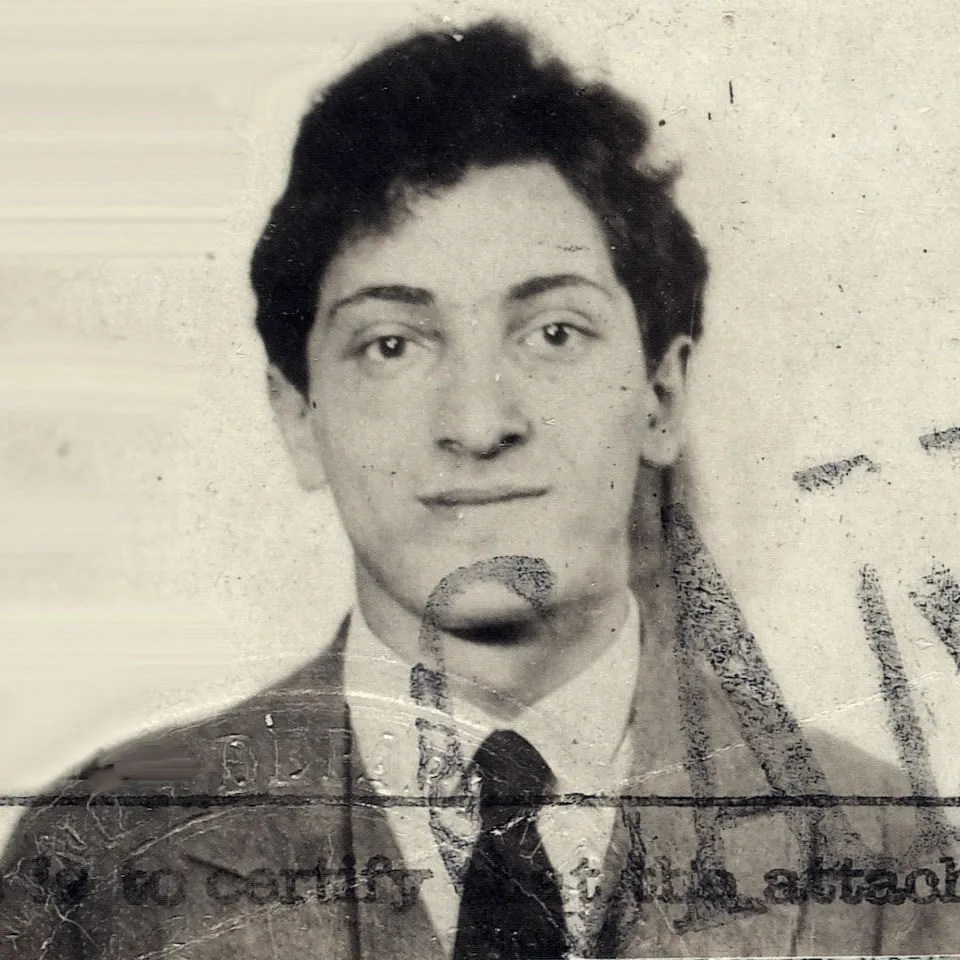

A major essay on our built environment offering a substantial critique of Lewis Mumford’s work, particularly his ‘Culture of Cities,’ from leading Marxist social and art critic Meyer Schapiro.

‘Lewis Mumford: Looking Forward to Looking Backward’ by Meyer Schapiro from Partisan Review. Vol. 5 No. 2. July, 1938.

IN THE PRESENT slump of socialist theory and with the revival of reformist programs, Mumford’s Culture of Cities has been welcomed as a major contribution to knowledge and to social thinking. The vast scope of the book, its boldness and breadth of statement, the abundant esoteric documentation, the palatable mixture of social argument and art criticism, the rampant healthiness of the author’s tastes, the wonderful timeliness of his appeal for new homes and regional planning, so close to the avowals of the government, all these considerations— secondary to truth and practicality—elevate the book in the minds of its reviewers as a monument of social prophecy and a tonic for discouraged men of good will.

The Thesis. Mumford traces the history of cities since the middle ages in order to formulate the possibilities of the good city of the future. He believes that the mediaeval town was socially and hygienically better than has been supposed, and still offers invaluable suggestions to-day not only as an example of sound urban planning, but also in its democratic communal life; the interests of all classes were harmonized then through their common enjoyment of the rites and pageantry of the church. It was at the end of the middle ages, with the rise of machine technology, despotism, militarism and capitalism, that the city began to assume its present unhealthy and hypertrophied forms. From the “will-to-power” Mumford derives the militarization of the city plan, the great boulevards, the architecture of pomp, the mechanical and unsocial regularity; from capitalist greed and indifference to biological needs, the “insensate” industrial town and the pollution of the whole environment. But during the last seventy-five years a reaction has set in. And in the newer ideals of regionalism, conservation and the garden city, all related to the emerging “biotechnic economy,” patterned on the organism, Mumford foresees a new civilization, the creation of which is the chief social and political problem of our time.

This summary gives no more than the large outlines and tendency of the book. Actually, together with Technics and Civilization (and a third volume on ethics and religion yet to come), it is an ambitious effort to write a history of modern culture and to set down the principles of a new society. It is conceived also as a work of public education, and is full of informative matter, often curious and delightful, touching on many more aspects of history than are ordinarily treated in books on architecture and planning. Mumford submits to the reader in a vivid, but often pompous, turgid, manner, the notions of advanced architects, city-planners and regionalists, as well as something of new historical research on the past solutions of similar problems.

Society as Style. Although his cultural history and social program are not really distinct, it is convenient for purpose of analysis to consider them separately. The first is especially interesting in its frequent appeal to styles of art as symptoms and data of social life. These styles, for Mumford, are not simply indications of how people thought and felt, they are also clues to the causes and value of the culture and are even regarded as pervasive habits of mind, governing science, economy, social relations and the state. Thus Mumford gives a paramount importance to the concept of “baroque,” by which he designates practically the whole of post-mediaeval society from the 15th century to the 19th. There emerges from his description the somewhat vague and shapeless image of the baroque man who eats, drinks, loves, trades, builds and reasons in a baroque style. For the analysis of the changing historical situations of building, trading and reasoning, Mumford substitutes the appreciation of the common baroque flavor of the builder, trader and scientist. Now this is also what he often does with our own society; its evils and virtues are made to flow from the special psychologies of the predatory and the “organic” man. On the whole, he tends to psychologize causes and to moralize effects. Of analysis of social structure or historical events or of the more intimate effect of city life on the arts, there is very little. Yet this writer, who accepts the “baroque man” as a fundamental fact and who appeals to a “resurgence of the organic” as the ground of revolution, rejects the capitalist class and the proletariat as “bare economic abstractions.”

Now while there is a value in isolating relatively widespread habits of thought in a culture or period, Mumford’s baroque as a stylistic concept is confused and inadequate. In the first place, it is applied to a lengthy period of time which is culturally so varied that the concept of baroque can hardly do justice to its historical richness. Even the baroque of a single moment, as described by Mumford, admits the most diverse and opposed qualities. And finally, his method of exhibiting the unity of the baroque rests upon an uncontrolled intuitiveness and merely verbal correlations.

During the last thirty years historians have restricted the term baroque more and more to a specific moment in the arts of the seventeenth century, distinguishing it from the preceding Mannerism and the subsequent Rococo and Classicism. They have also defined within the baroque various types, stages and regional tendencies and given the term qualifying nuances which permit a somewhat more precise historical discussion. Mumford, however, throws all this overboard and, on the assumption that the term is bound to be stretched anyway, extends it over a period of four hundred years to include Brunelleschi and Horace Walpole, Uccello and Turner, and to cover qualities so contradictory that the existing ambiguity of the term becomes a rank confusion and the name is rendered useless for characterization. The baroque is the regular and the irregular, the massive and the minute, the ascetic and the sensual, the anti-organic and the naturalistic. (This ambiguity appears also in the uncertain etymology of the word: “baroque” has been derived from a word for an odd shaped pearl and from the name of a scholastic syllogistic form). Mumford himself seems to enjoy this union of opposites within his favorite category. But his stylistic license also permits him to obscure the relations of the bourgeois and the aristocratic during this period, and to impose a monolithic unity on the culture. He deduces almost everything from the psychology of the mythical baroque individual, who is at once despotic, military, pompous, gracious, exact, orderly, wasteful, libertine, protestant and authoritarian. The newspaper, the “archaeological cult of the past” and even the clock (which he has elsewhere described as monastic and bourgeois in spirit) are now characterized as baroque. Just as the effort to measure or define the moment is called baroque, the baroque is identified by Mumford with the limitless, and by this psychology of style he moralistically explains the behavior of the time: “the notion of limits disappeared: the merchant cannot be too rich, the state or the city too big”; “the feverish desire to get somewhere” is “a manifestation of the pervasive will-to-power.” If we adopted his approach and tried to name Mumford stylistically after his method, we should call him a liberal expressionist with veiled bureaucratic tendencies: he has the closest affinities with Spengler, for if they differ in their conclusions, they are often similar in method and form.

The Method of Analogy. Like Spengler he indulges in a crude analogical thinking which at its best may be called geistreich, but hardly profound; sometimes it is based on downright misunderstanding. Take for example his deliverance on Renaissance painting that “this putting together of hitherto unrelated lines and solids within the rectangular baroque frame—as distinguished from the often irregular boundaries of a mediaeval painting—was contemporary with the political consolidation of territory into the coherent frame of the state.” If by this reference to politics, the forms in painting seem to arise from a field beyond the canvas, although the connection is left vague, on the other hand the political movement becomes stylistic and characterological, like the work of art. But no historian of art will take the comparison seriously, not only because of the flimsiness of the verbal analogy of the political and the pictorial forms and the ambiguity of the stylistic terms, but because of the familiar facts that 1) the rectangular frame is a common mediaeval type, 2) the nonrectangular forms are often regular and coherent, 3) the perspective organization of the pictorial space is known long before the political changes in question, 4) baroque art also cultivates the irregular and non-rectangular frame, 5) and finally, the baroque is used by Mumford to designate art from the 15th down to the 19th century, a period during which perspective, frames and composition undergo pronounced changes and include irregular, boundless and mobile forms.

In the same way, because the processes of mining are “destructive” and “anti-organic,” he explains the “general loss of form throughout society” in the 19th century by the predominance of mining; “the destructive imagery of the mine…is carried into every department of activity, sanctioning the anti-vital and the anti-organic.” We may disregard the mysterious animism of these judgments. But it is apparent that the good architecture of the past has required quarrying and lumbering, which by Mumford’s criteria destroy nature, and that cultures sustained by hacking activities have not been without form. Interestingly enough, it is in the practical metal architecture of the 19th century that Mumford finds the most satisfying formal order and the “organic” tendencies of the future. And Impressionist painting, which is for him the culminating point in formlessness, he also values as a manifestation of the organic, as a healthy reaction against the griminess of the industrial city.

Architecture and Society. Although he regards architecture as a simple reflection of society, their relations are anything but clear in Mumford’s account. He does not limit himself to architectural forms or uses depending directly on the social objects in question, but dogmatically derives the artistic value of buildings from their social origin. At one point, having condemned the society of the post-mediaeval period as anti-vital, he must condemn its architecture as socially dead. This period “shows the fatal lack of connection between architecture and the dominant social sources of order.” The proof that “architecture in the social sense was dead” lies in “the series of dusty revivals that took place…society itself is the main source of architectural form; only in terms of living functions could living form be created.” These banal tautologies and prejudices presuppose an indifference to the qualities of post-mediaeval architecture incredible in Mumford; it must issue from his prophetic zeal, not from his sensibility. When he admires a building, he infers that it is connected with the “dominant social sources of order,” or with some still healthy part in a diseased organism; if it is bad, then it lacks such a connection. Hence if he values the work of Richardson (1838-1886), he is led to conclude—on what evidence, I do not know—that this great architect was basing his art “organically on the technical resources and social principles of the new society,” and that “he entered deeply into the problems of his age and became familiar with its social and economic forces.” Richardson “proved that organically conceived, a railroad station had no less capacity for beauty than a mediaeval fortress or a bridge.” But what has all this to do with the social principles of a new society? Richardson in his forms still clung to the past. He used traditional materials and accepted the existing social order no less than the inferior builders of his time. His successful constructions were made for the very men whom Mumford cannot condemn enough as ruthless despoilers of the environment and enemies of the organic. In designing the great warehouse in Chicago for the notorious land speculator, Marshall Field, Richardson accepted the contemporary city and commercial needs: it was built to suit the interests of a man who, by Mumford’s criteria, was personally responsible for much of the evil of the Chicago environment. Mumford betrays himself again when he cites “Berlage’s handsome Bourse in Amsterdam as a parallel example of great force and merit”; this is precisely a building which serves the financial functions that Mumford never tires of denouncing.

The criticism of post-Renaissance architectural revivals as a sign of impotence is too easy and superficial; it induces the false conclusion that because we have a style of our own, our society is more healthy and ordered. By proceeding from literature, music and painting in the same reductive spirit, one would have to draw the opposite conclusion. The charge of stylelessness in architecture has been repeated already for a hundred years, but it is becoming more and more evident how much the architecture of the 20th century owes to these revivals and what originality some of them possessed. Their nature is hardly exhausted by their imitative aspect. The values of a geometrical, elemental simplicity are already clear in neo-classic architecture (Ledoux, Soane and Schinkel have an imposing modernity); and the Gothic revival undoubtedly affected the modern taste for elusive, incommensurable arrangements and the interest in technical sources of forms, whatever the misunderstandings of the neo-Gothic architects (echoed by Mumford!) about the constructive and functional character of Gothic buildings. Conversely, Mumford tends to accept the programmatic definitions of functionalism uncritically, on their face value. And in assimilating, as he does, modern architectural style to cubism, which is anything but organic and social in his sense, his social judgment of the style becomes even more mysterious and confusing. If republican Germany produced it and the Nazis have restricted its use, it should also be remembered that the Italians have in turn welcomed it as “rational architecture.”

Mysticism of the Organic. His stylistic concepts and analogies are not merely incidental to Mumford’s program; they are material assumptions and elements of a method which, when applied to our own issues, entail his reformist outlook. Just as he describes the past in terms of a baroque style and lifeless revivals, expressing social decay, so the new civilization is described as an “organic” style already evident in the later 19th and the 20th century, apart from actual economic and social relations. To complete the new tendency, inherent for Mumford in the psychology of new forms of technique and in a spontaneous, unlocalized feeling for the organic, one must rebuild the environment and get rid of bad obstructing habits inherited from the past. “Biotechnic standards of achievement must produce a system of values destructive to metropolitan finance.”

There is an engaging historical dialectic in Mumford’s conception of the modern “organic style.” The universal middle ages are organic on a local, ascetic, un-technological level; the nationalistic, baroque technology denies the organism; then, annihilating and uniting both, the new civilization (our own), regional and international, is organic through greater mastery of technique. But nothing is more unclear than Mumford’s idea of the organic. In both books an object is certified as organic if it is alive or extremely complex, if it serves or pertains in some way to a living being, or if it is an institution responsive to the biological needs of all individuals. So, to establish the organic sources of modern architecture, he points to the fact that the Victorian Crystal Palace—a gigantic showcase for industrial arts that by Mumford’s standards are anti-vital and decadent—was the design of a gardener inspired by the greenhouse, and that the first applications of concrete were in gardening. But with as much plausibility one might argue that modern architecture has a religious origin since the first building entirely in concrete was a church (1894); or one might say that it is basically commercial, since iron and glass were applied together even earlier in the Halles and Passages, the grain markets and shopping arcades of the early 19th century. His organicizing of inventions and societies is even more subtle. The telephone, the airship and contraceptives are for Mumford organic, whereas the telegraph, the railroad train and the printing press are merely mechanical. Feudalism, in which he mistakenly supposes the class struggle abated under the happy spiritual sovereignty of the church, he considers more organic than capitalist society; in this opinion he joins hands with the modern Catholic ideologues of the corporate state. And in an astonishing passage which we must lay to his historical shortsightedness, he unwittingly presents his organic ideal as a kind of mediaeval totalitarianism; he reproaches Protestantism in the 16th century as socially antiorganic and as having “further destroyed the possibilities of creating a united front.”

In his fuzzy organicism, Mumford also cultivates that fringe of inspirational scientific metaphor common among world-saviors and neo-religionists to-day. Like a romantic Naturphilosoph he equates the mechanical with the visible, the organic with the invisible—he cites rays, emanations and dreams!—and insists that the latter “are as real…as any external phenomenon.” The polarity, organic and inorganic, corresponds for him to that of quality and quantity; and he opposes the science before 1870 to science after 1870 as mechanism to organism. Sad dilettante muddle of Whitehead, Bergson and ABC’s of the cosmos! He must be aware that the mechanism of the 17th century presupposed particles that no one had seen and invisible attractions through distant space, and that mechanistic physics was full of concepts derived from the experience of the human body; whereas the growth of the biological sciences in the last century has depended largely on the application of the methods of physics and chemistry to the living organism, and it is the classical mechanics which is applied in these sciences.

In Mumford’s writings, the polar twins, organic and inorganic, are often nothing but heavily weighted homiletic counters, like the metaphors, life and death, light and darkness, in older religious speech. In characterizing an object as organic, Mumford sanctifies it, endows it with an aura. And in spite of his strenuous espousal of the organic, his social analyses, in their reduction of issues to bare polar conflicts, are often mechanical and primitive, and congested with Newtonian categories of mass, force, inertia and space: “our failure even to contrive a breathing space in bellicose effort is partly due to the inertia of historic burdens.”

Political Program. The counterpart of this rousing faith in the organic and the emergent is the political abstractness of Mumford’s partisanship of a new social order. It is not as if he is bringing us new values which have first to be understood and absorbed; he is reaffirming the long-recognized need for basic changes in society. But when we look for discussion of the means, we find nothing but pious rhetoric or revolutionary bluster. The following is typical: “Instead of clinging to the sardonic funeral towers of metropolitan finance, ours to march out to newly plowed fields, to create fresh patterns of political action, to alter for human purposes the perverse mechanisms of our economic regime, to conceive and to germinate fresh forms of human culture.” One might imagine from this passage that he has serious political views; but nothing is more characteristic of Mumford as a social thinker than his general aversion from politics and his unclarity about the nature of the state. The mythical aggregate to which he constantly appeals, the undifferentiated we’s and ours’ of his tumescent proclamations, are his alternative to class groupings. True, he encourages “political association” as a kind of healthy activity, in the way settlement workers promote boys’ clubs (he names Sunnyside, L. I.—alas! —as a model of “robust political life”), and laments that “the saloon and the shabby district headquarters” have been the chief political clubrooms: “One of the difficulties in the way of political association is that we have not provided it with the necessary physical organs of existence: we have failed to provide the necessary sites, the necessary buildings, the necessary halls, rooms, meeting places.” But like so many honest reformers who fear the self-interest and blatancy of politics, he wishes finally to preserve his political virginity. Although he acknowledges the existence of the labor and socialist movements, essentially he regards them from outside, as possible aids to the independent, public-spirited reformer. He has adopted some socialist phrases, but is ignorant of socialist literature and its analyses of the questions he deals with. In a patronizing mood, he tells the reader that socialism arose in the slums; on the contrary, it is a product of critical members of the bourgeoisie, of their science and speculation as well as their moral idealism. Its history is only slightly affected by intellectual contributions from the slums. But is there a clearer sign of political naiveté than his regret that “society” hasn’t provided meeting places for the workers: “in how many factory districts are there well-equipped halls of sufficient size in which the workers can meet?”

It is typical of his provincial misunderstanding of the relations of politics and society that he can sweep aside the politics of the 16th to the 19th century as “crazy statecraft”; Mumford, had he been there, would have acted differently and is therefore full of regrets in discussing the mistakes of the past. He moralizes on politics, as on everything else. Yet in his own mind he remains a practical theorist and expresses contempt for those who do not see the immediate realities: “Plans that do not rise out of real situations, plans that ignore existing institutions, are of course futile: mere utopias of escape.” What then shall we say of his own vagueness about the problems of the moment? In one place, excited by the obstacles private ownership of the land puts before sound urbanism, he writes that “public control of land…is the outstanding problem of modern statesmanship”; elsewhere, “regional rebuilding is…the grand task of politics for the opening generation.” But finally, “perhaps the most critical problem for human society to-day is that of diminishing the role of the power state and undermining both its pretensions and its ultimately militaristic forms of authority.” Yet he deals politically with none of these outstanding, critical problems and grand tasks, and fails altogether to evaluate the difficulties or to throw light on the means of transition. The belligerent talk of revolution in this book is mere bluster in view of his neglect of the cold facts of class power. Mumford does recommend a practical measure: he “prefers,” he tells us, “outright expropriation with drastically limited compensation” in the form of pensions to the owners of the land. This “preference” is the sum of his revolutionary political meditations.

The Power and Service States. The key to Mumford’s political ideas may be found in his concept of the state, which is based on the writings of Geddes and Branford. In general, Mumford, who is so lyrical about the objectiveness of modern technics, evades names which help to illuminate their objects. He calls feudal absolutism “the baroque state,” capitalism “the power state,” and democracy “the service state.” The power state is that “creation of the baroque imagination” out of which has grown the service state through democratic pressure to “reapportion the existing balance of power within the nation, to equalize the privileges of different regions and groups and to distribute the benefits of human culture.” From this account, which seems to substantialize certain functions of the state as an independent state within the state, it would follow that by gradually expanding the service state, one could finally crowd out and eliminate the power state. This is an historically false view of political liberalism, disregarding its bourgeois roots and aims, the close relations between power, interest and service, and the ultimate dependence of the modern state upon the economically dominant class. In the United States, he says, “the activities of the Department of the Interior, the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Commerce, the Forest Service, the Parks Service, the Children’s Bureau, are examples of the service state.” The service state is thus simply a branch of the power state; when the government builds roads, or promotes commerce, it is a service state, when it protects property or makes war, it is a power state. But from which of these functions can we best deduce the response of the “democratic” state, with all its service departments, to strikes, crises and wars? Mumford considers the power state something abnormal and perverse and the service state as proper to society itself; but he fails to observe that if “irrationality and obsessive mythologies” are inherent in the power state as such, the Nazi state has also increased its service functions. Just as his service state has grown out of his power state, we have now the example of fascism growing out of that republican Germany which is for him the highest example of the service state in modern times. It is trivial to identify, as he does, the emergence of the Nazis from this biotechnic paradise of healthy, organically inclined Germans with atavism and pathological traits. Such a view disregards the class tensions, the precarious life of republican Germany, and the fortunes of German capital during the world crisis. On the whole, Mumford tends to confuse not only the particular state functions and the social order, but also the state and the governmental regime. Hence his peculiar metaphors of disease and insanity to characterize the evils of the modern state, as if these evils were mal-functionings of society, weaknesses of a single infected organ, rather than results of the structure as a whole. If he has accepted from radical critics the analysis of imperialism as an economic and political outgrowth of capitalism, he also speaks of it as if it were best understood and dealt with psychologically. Race doctrines are dismissed as “crazy dreams,” to be treated as “definitely pathological,” like the imperialist. desire “to fill out the national boundaries.” The educational correctives of this “wanton mythology” are the rational regionalist’s facts, the unity of mankind. The present division of world empires he regards, with the have-not ambassadors, as an “intolerable anachronism.”

There is in Mumford’s book a core of sound and familiar observations: the development of capitalism does indeed entail a more and more thorough socialization of production and interdependence of functions; the state forms more and more “service” departments; and modern economy in its world character transcends political boundaries. But in abstracting these facts from the structure of capitalist society, in neglecting their historical incidence, he lifts them out of the field of class relations in which their reactionary or socialist outcome will be largely determined.

The Basic Communist. Mumford seems in places to accept the socialist and communist goals, but is careful to qualify them by honorable, apotropaic adjectives (“humanitarian socialism,” “basic communism,” “cooperative communism”), as if to distinguish his own ideals from the unhumanitarian, superficial and uncooperative Marxist kind. He is evidently superior to socialism as a political movement.

This bias appears in his incapacity to understand the simplest socialist statements of the same problems. In criticism of Engels on the housing question, he writes that Engels “not merely opposed all ‘palliative’ measures to provide better housing for the working classes,” but held “the innocent notion that the problem would be solved eventually for the proletariat by a revolutionary seizure of the commodious quarters occupied by the bourgeoisie,” quarters which Mr. Mumford in his boundless sympathy with the masses rejects as “intolerable superslums.” He calls Engels’ proposal “merely an impotent gesture of revenge,” while his own solution—‘‘increasing the amount of housing, equipment and communal facilities’—he considers to be “far more revolutionary in its demands than any trifling expropriation of the quarters occupied by the rich would be,” for it “demanded a revolutionary reconstruction of the entire social environment—such a reconstruction as we are on the brink of to-day.”

Let us leave him on the brink and read what Engels actually wrote in 1872 in answer to the Mumfords of his day.

“How a social revolution would solve this problem (of housing) depends not only on the conditions at the time, but also on much more far-reaching questions among which the abolition of the antagonism of city and country is one of the most essential. But since we are not designing a utopian system for setting up the future society, it would be more than idle to go into such questions. But this much is certain, that there exist in the great cities enough dwellings which if rationally used would satisfy the actual need for shelter.”

It is evident that Engels did not regard the division of existing space as the “eventual solution,” but only as an immediate step and part of a more general expropriation. Like other socialists of his time he foresaw the ruralized city as the real locus of the solution. The criticism of palliatives was not a rejection of all improvements in building —as Mumford would have his readers believe—but an assertion of the impossibility of solving the housing problem of the masses under capitalism, an assertion which Mumford now repeats in this book. But whereas Engels also observed the role of philanthropic housing projects in dulling the worker’s insight into his social experience, and the military and class functions of the city-planning of his time, and therefore warned the worker against them, Mumford continues like his forebears of the 70’s to promote the illusions. If he states again and again that to posit these ideals of housing is to demand a revolution, he repeats no less often that the revolution has already begun, that we are on the brink of basic socialism since Radburn, New Jersey, has been completed. But even here he straddles, and reveals his underlying indecision: it is not capitalism which stands in the way of housing, but “unregulated private capitalism.”

Mumford’s Tradition. He repudiates the charge of reformism, but has not tried to indicate how his position differs from what is currently called reformism, or to come to grips with Marxist criticism of views like his own. He has often acknowledged without critical reservation a deep indebtedness to Patrick Geddes who was undoubtedly a reformist, opposed to revolutionary change. The enterprise of Mumford in writing Technics and Civilization and The Culture of Cities recalls the series edited by Geddes and Branford after 1917— The Making of the Future. Reading their volumes in this series, one is surprised to see how little Mumford has advanced beyond them after the events of these twenty years. He shares not only their reformist views, but even their turn of phrase, their style of thought— although he is more passionate and blustering, more emphatically responsive to the aesthetics of the environment. No doubt their optimistic ideas of reform through good will are still Mumford’s. They are regionalists, city-planners and nature-lovers who call upon all men of good will to build a new civilization. Like Mumford, they hold up the middle ages as a period of democracy and organic society. Their reference to de Maistre and Bonald as sources indicates the narrow distance which sometimes separates them from contemporary reactionaries who also speak of regional culture, the unified community and the decentralization of the big cities. And when we read their remarks on the war, with their hopes of a new civilization arising from the defeat of Prussianism, we seem to be reading Mumford’s call to war against the fascist states. They link Prussian Militarism and Competitive Big Business in the way people now link Fascism and the Two Hundred Families. Their anti-profiteering and anti-monopoly views were readily turned against the German enemy of the native monopolists. “Prussianism and profiteering are thus twin evils. Historically they have risen together. Is it not possible that they are destined to fall together before the rising tide of a new vitalism? The reversal of all these tendencies, mechanistic and venal, would be the preoccupation of a more vital era than that from which we are escaping. Its educational aim would be to think out and prepare the needed transition from a machine and a money economy towards one of Life, Personality and Citizenship.” They even welcomed the war as “a spiritual protest and rebound against the mammon of materialism,” the “vastest of social experiments in the problem of coordinating communitary and private interests.” We seem to be listening to Mr. Mumford, when we read these lines from a series dedicated to “the Philosopher-Statesman,” Woodrow Wilson. It is not simply their acceptance of the war that we recall here, but the way in which their humanitarianism was invoked to justify it and to create popular illusions concerning its nature and outcome. Mumford too denounces capitalism; but in psychologizing it, in veiling its historical and social character in moral categories, and in regarding it as almost socialist, he is able to support it. If it includes both power states and service states, it becomes right to support one’s service state against the enemy’s power state.

To-day, when Marxists, liberals, fascists and Christians all condemn capitalism, Mumford’s denunciation is not in itself crucial. It is especially consoling to those who find capitalism intolerable, but the overthrow of capitalism equally unpleasant. He assures them that capitalism is dying and that the new society is already growing up in the form of garden cities, suburbs, new houses and superior streamlined machines, the very things by which the middle class measures its own well-being. The field of revolution lies for him in the fixtures of society, rather than in class relationships. By psychologizing the latter, he reinstates the unattached man of good will, who finds in his spontaneous tastes and sympathies the test of political theories. By treating capitalism as one vast slum or super-slum and the capitalists as vicious or pathological elements, he implies that social work and model resettlements are the effective instruments of change. In his fulsome announcements of pre-arranged social agenda, he is the ideal chairman of the supernational and classless congress of men of good will, a congress at which practical difficulties are evaded and the drums of imperialist war play a humanitarian music.

Partisan Review began in New York City in 1934 as a ‘Bi-Monthly of Revolutionary Literature’ by the CP-sponsored John Reed Club of New York. Published and edited by Philip Rahv and William Phillips, in some ways PR was seen as an auxiliary and refutation of The New Masses. Focused on fiction and Marxist artistic and literary discussion, at the beginning Partisan Review attracted writers outside of the Communist Party, and its seeming independence brought into conflict with Party stalwarts like Mike Gold and Granville Hicks. In 1936 as part of its Popular Front, the Communist Party wound down the John Reed Clubs and launched the League of American Writers. The editors of PR editors Phillips and Rahv were unconvinced by the change, and the Party suspended publication from October 1936 until it was relaunched in December 1937. Soon, a new cast of editors and writers, including Dwight Macdonald and F. W. Dupee, James Burnham and Sidney Hook brought PR out of the Communist Party orbit entirely, while still maintaining a radical orientation, leading the CP to complain bitterly that their paper had been ‘stolen’ by ‘Trotskyites.’ By the end of the 1930s, with the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, the magazine, including old editors Rahv and Phillips, increasingly moved to an anti-Communist position. Anti-Communism becoming its main preoccupation after the war as it continued to move to the right until it became an asset of the CIA’s in the 1950s.

Access to full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_partisan-review_1938-07_5_2/sim_partisan-review_1938-07_5_2.pdf