One of our movement’s essential historic publications, this valuable history of the I.W.W.’s newspaper ‘Solidarity’ from its editor B.H. Williams is also an excellent read.

‘Solidarity’s Struggle for Existence’ by B.H. Williams from Solidarity. Vol. 4 No. 52. January 3, 1914.

IN THE latter part of August, 1909, the undersigned landed in New Castle, Pa., after an uneventful “hobo” trip from Chicago, with Fellow Worker Frank Morris. We were, as usual, hungry and broke. We found a little bunch of workers in an alley basement, folding up the current issue of a little three-column sheet called the “Free Press.” There were among them several good I.W.W. rebels. The McKees Rocks and Tin Mill Workers’ strikes were in full blast. The city and county officials of New Castle had been pulling off some raw stunts against the strikers, and the “Free Press” was filled with rebel dope dealing with the situation.

Here we met Fellow Worker C.H. McCarty, who at once outlined a plan for starting an I.W.W. paper in New Castle. McCarty had no personal ambition in the matter. He was not a writer, or speaker, and did not aspire to “shine” as a leader. EDUCATION had always been his “hobby,” and he saw the need of it more than ever, with the awakening spirit in the Pittsburg district. McCarty’s was an aggressive spirit, and he had won the reputation of never falling down on anything he undertook. The rebels were enthused over the proposition, and the writer, who landed a job in a printing office shortly after his arrival, decided to remain in New Castle.

In September, 1909, plans for starting the new paper began to materialize. Some difficulty was encountered in choosing a name. Finally the promoters decided upon the one which I proposed “SOLIDARITY.” A press committee, of three each from the two I.W.W. locals, was chosen; prepaid sub cards were printed and sent out all over the country with circular letters calling for subscriptions in advance. More than 10,000 circulars, with 40,000 sub cards were mailed to addresses in our possession. The Solidarity press committee consisted of C.H. McCarty, Valentine Jacobs, Earl F. Moore, Geo. Fix, B.H. Williams, and one other, who, however did not serve. A.M. Stirton, formerly editor of the “Wage Slave” of Hancock, Mich., was chosen editor. Although Stirton’s experience in the labor movement, outside of the Socialist Party, had not been extensive, he had a vigorous style of writing, and was not averse to taking a suggestion. McCarty was made business manager, and the undersigned was promised the position of “official typesetter,” at the munificent salary of $8 per week, with the “possibility of a raise.” The business manager was expected to work without salary. Thus we were prepared for emergencies.

Returns on the sub cards amounted to some $700 by the end of November. With this money, and a small loan of about $200 from the Pittsburg District Council of the I.W.W., about $400 of type and other printing material was purchased, a space rented for the same in the “Free Press” office, and the first issue of SOLIDARITY printed on December 18, 1909. Under arrangement with the Free Press company, our press work was done by that concern, which charged us the excessive rate of $2.50 per thousand for simply putting the papers through the press. This alone amounted to $50 per month for an edition of 5,000 copies, and as we shall see presently, got us into financial difficulties. Within three months the paper was in danger of suspension, from lack of financial support.

Then came an unexpected rift in the clouds. The steel trust-owned officials of Lawrence County “came to our rescue.” Having previously, through a Pinkerton detective, se- cured the signatures of the two press committees (that of the Free Press and Solidarity) to a fake “piano advertising contract,” on March 1, 1910, warrants for the arrest of all members of both committees were served on all except the undersigned, who was critically ill in the hospital at the time. The charge against both papers was, a technical violation of the Pennsylvania Publishers’ Law, which required the names of all OWNERS on the editorial heading of publications. Although Solidarity’s heading specified that it “Published by the Local Unions of the I.W.W. in New Castle,” giving names of editor and business manager, that was deemed insufficient. The authorities expected to put both papers out of existence, and save the annoyance of their menace to steel trust “law and order.”

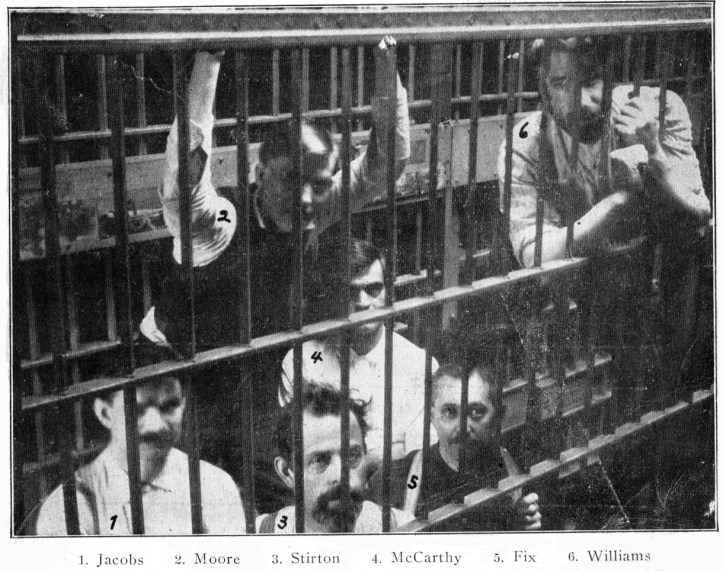

The Free Press hired a “comrade” lawyer, who charged them some $300 and lost the case easily. The next day, March 17, 1910, the case of Solidarity came up for trial. We had previously determined to use “direct action” on the court. That is, we refused to hire an attorney, demanded the privilege of pleading our own case, and agreed to pay no fines, if convicted. The Free Press had no names on its editorial heading, and therefore the prosecution had an easier case than with Solidarity. We went directly at the matter, made no unnecessary denials, and insisted that we were acting within the law, having no reason whatsoever for violating the same. Our attitude and plea to the jury caused some fear on the part of the district attorney and his assistant, that they might not make good. So after the fury had been charged by “hizzonor” and Brose ready to confer on the case, the assistant prosecutor pulled off a little joker in Pennsylvania jurisprudence, by asking the judge compare our heading with the statute, and inform the jury as to whether or not the two agreed. The judge complied in detail, much to our surprise, stating as his opinion that in at least two important details the heading in Solidarity was not in conformity with the statute. What could a poor jury do, in a case like this? The judge surely “knew the law,” and the jury was deprived of all responsibility for the verdict of “guilty,” which followed. Called up for sentence on March 23, we gave reasons why sentence should not be imposed, which were, of course, overruled, and each member of the Solidarity press committee, as well as Editor Stirton, was fined $100, with some $80 of costs added to the case. We refused to pay, and were handed over to the sheriff and locked up in the county jail. The Free Press committee filed a motion for a new trial, which was subsequently denied.

Here, again, the energy of McCarty asserted itself. Immediately after our conviction, he insisted on having an appeal for funds prepared and sent out. The appeal asked for money, not to hire lawyers or pay fines with, but TO KEEP SOLIDARITY ALIVE WHILE WE WERE IN JAIL. Thousands of these appeals were mailed before sentence was imposed, and others were made ready inside and smuggled out of the jail. Fellow Worker Grover H. Perry was given charge of the paper as business manager, and Fellow Worker H.A. Goff called to the editorial desk. The editor and five members of the press commit- tee spent 92 days in the jail, after which all but one were released by the commissioners, on a plea of “pauperism” (being without property with which to pay fines) in due accordance with Pennsylvania law. Our jail experience was “most delightful,” in marked contrast with that of the fellow workers then suffering in the Spokane bull pens. The women of the Socialist Party and others furnished us with the finest “eats” some of us ever had. We were only locked up in cells two or three nights, having the freedom of the corridors day and night. We were treated most courteously and kindly by the sheriff (good old Sheriff Whaley, “too humane for that job”); allowed more than our share of visitors; had all the papers to read; and wrote articles for the paper from the inside. We laughed and grew fat, much to the chagrin of the authorities. Meanwhile our appeal for funds netted several hundred dollars, and we joked about the Pinkerton and his “piano ad,” saying we got paid double rates and more for that advertising. The paper was undoubtedly kept alive with the money sent in by organizations and individuals all over the country. Fellow Worker Goff held the editorship for several weeks, until financial retrenchment became necessary, when Perry was given entire charge until we came out of jail. DIRECT ACTION had scored another victory!

The effects of our action in the court, and in going to jail rather than pay the fines, were apparent in the subsequent action in the “seditious libel” case against the Free Press. We turned the sentiment of the community against the authorities, and, with the aid of a good lawyer and a defense fund secured largely by exploiting our imprisonment, the “seditious libel” case was won for the defendants. We also saved the Free Press committee from paying their fines on the same charge as that against us. After denying the motion for a new trial, the Free Press committee was called to court for sentence, and the judge remitted all but one fine and the costs, the “same as in the case of Solidarity.” The reason we had to pay one fine and costs was because Fellow Worker Jacobs had signed the bail of McCarty, and was therefore subject to having his little property levied for the court costs. But Jacobs served his time in jail with the rest of us, just the same. Even at that, the Solidarity case, cost the county some $300 or $400 more than they got back. The taxpayers got sore, and the authorities left us alone after their sad experience.

But, while Solidarity came out of this little ordeal with flying colors, it was only to face the two-fold ordeal of petty tyranny on the part of the Free Press-gang, and of financial stringency, which compelled us to submit. At the suggestion of Fellow Worker Stirton, I became editor of Solidarity immediately after our release from jail. McCarty resumed the business management. I well remember how, the first week, I presumed to “be a real editor.” That is, I thought we could hire the mechanical work done, while I spent my time attending to my duties as editor. The end of the first week dispelled the illusion. McCarty figured up the finances, handed me $6 for living expenses, kept $5 for himself, and good-humoredly announced that there was a balance of 39 cents in the bank. Monday morning I doffed my “Sunday best,” put on my work clothes, and took my place at the type case, discharging one of the typesetters. Three days a week at hard mechanical labor, and the fourth day helping fold and mail papers, was the writer’s portion during the remaining six months that we kept our printing material in the Free Press office. Every day I had to grind my teeth while keeping my mouth shut, at the petty annoyances and ill-concealed hostility of the Free Press “comrades.” Here I learned beyond a doubt, that aspiring politicians and direct actionists have nothing in common, and can’t be harmonized. The Free Press got a fat thing out of Solidarity in a financial sense, but their short-sighted managers were only too anxious to catch us in financial difficulties and put us. out of business. McCarty alone was able to stave them off for awhile.

Their opportunity, however came in September, 1910. The long-drawn out tin mill strike was over, and McCarty found that he was blacklisted in New Castle. Heavily in debt after 16 months of strike, with his wife’s home threatened, he was compelled to leave the office and seek employment out of town. At no time had he drawn more than $5 a week as business manager, while my wages were from $6 to $7. In spite of such retrenchment, however, we could not keep even with rent, paper bills, and press work, and began to accumulate a small debt with the Free Press. The debt amounted to a little over $150 by September. Then a move was made by the Free Press managers through the Socialist Party local, to shut off our credit. No other firm in town would handle our press work. We must get the money, besides making a I move to get our own press. A hurried call for funds netted about $70, which was applied to the debt, and kept it from accumulating as fast as it might otherwise. This appeased the Free Press crowd to the extent that the S.P. local decided late in September to extend credit to Solidarity until the first of the year. We then issued a call for a Press Fund, and McCarty and I jokingly set the date of December 17 as the time when we should order our press. There was no money in sight at the time, and the press fund was not materializing to any extent. The status of Solidarity looked desperate. But about the first of December, Fellow Worker Korn of St. Louis, came to our rescue with a loan of $200, without interest, for an indefinite period. December 20, three days after the date previously set in a joke by McCarty and myself, we sent a man after a cylinder press. December 24, the S.P. local decided that no further credit for press work should be extended to Solidarity. Our press was on the way, but had not yet arrived. On that day we moved our stuff out of the Free Press office. We expected to miss the next issue, but the Free Press managers put a different construction on the action of the local, and told us to bring our forms down to be printed. So our issue of December 31, 1910, came out as usual. But that very evening, the S.P. local emphasized its previous action, and refused all further credit. At that very hour, unbeknownst to them, our own press was being set up in our new location. The issue of January 7, 1911, was printed on the new press. We owed the Free Press about $230, which was finally paid in November, 1912.

But, now, you say, our troubles ended. Aber nit. They began. Our income during that fateful month of January, 1911, amounted to $151. Fellow Worker Frank Morris, who had taken the place of McCarty, and myself, drew about $6 a week apiece for expenses. We paid $5 a month rent. I reduced the time of the A.F. of L. typo to sometimes less than three days a week, by setting the extra type myself. Fellow Worker Horn acted as pressman and general utility man at a wage of $9 per week. February found us vegetating on an income of $140, and the end seemed near. “Appalling gloom” settled over the little dump in the New Castle alley.

Somewhat daunted we nevertheless issued an appeal for more press fund, with which to buy a job press and paper cutter. Pamphlets and leaflets were impossible without them. Practically nothing resulted in the way of donations.

McCarty’s dream of a publishing bureau in connection with Solidarity, was not materializing very rapidly. But March brought us a little sunshine in the form of increased income, and about the same time another saviour came to our rescue in the person of Fellow Worker John A. Becker, of Sheridan, Wyo., who offered to loan us $300 of his meager life’s accumulations. So we landed the job press and paper cutter, on very easy terms, and began to figure on some pamphlets and other job work. Had it not been for the two loans above-mentioned, together with a few smaller ones from local unions and the general office, Solidarity’s days would have been numbered three years ago. We were constantly handicapped in office work by lack of income, and with having our noses too close to the grindstone of mechanical work, to be able to do any energetic promoting, which might have brought increased income from subs, bundles and literature. The locals were supporting two papers, and as the greater amount of agitation was going on in the West, naturally the Industrial Worker was given the preference. I tried hard during those months, as I am still trying, not to put any of the “office gloom” in Solidarity, but it must be a miracle if I have succeeded. I have only consented to write this narrative, to show our readers and supporters, if possible, what it takes to maintain a revolutionary press. More co-operation now and in future, will relieve the “office” burdens, and inspire all the boys on the job here with renewed hope.

Following the events above recorded, we found our income somewhat improved. Pamphlets were issued in good-sized editions. Thousands of leaflets were published and sold. An occasional loan for pamphlet stock, from the General Office of the I.W.W., helped to keep such paper bills paid. During the nearly three years in which I have had practically the entire financial as well as editorial responsibility for Solidarity and the I.W.W. Publishing Bureau, I have worked on the principle of always meeting obligations when due. Seldom have we fallen down. But many a time I have paced the floor, wondering how the devil it could be done. Uncertainty has ever been the order of the day. Since Solidarity started, we have secured between $2,500 and $3,000 in loans, the largest being $1,000, which we obtained from the General Office for equipment in the Cleveland plant. These loans were nearly all without interest, by locals and sympathizers; and a goodly proportion of the total amount has been paid back in literature. It has taken these sums in the form of loans, together with the combined support of West, East, and Foreign, on subs, bundles, literature sales and job printing, to maintain the paper and printing plant. Yet our expenses were never as great as those of the Industrial Worker. Even with this income, which has averaged about $500 per month during the past year, exclusive of loans, the closest possible supervision of finances has been necessary. At no time have I drawn more than $12 a week as editor, except for one month in New Castle. The present office and mechanical force of five men, are each receiving $12 a week. None of these boys has ever kicked for a raise. They understand the situation, and are only concerned about making Solidarity and the I.W.W. Publishing Bureau a power for the education of the workers.

After finances started to improve somewhat in New Castle, another handicap began to grow ominous. That was the inability to obtain efficient help, or to hold it for any length of time. No worker with a family could stand the pressure of a $12 a week wage scale. The Puritan atmosphere of New Castle very quickly became intolerable to a “hobo” afflicted as most of them are, with the spirit of wanderlust. After training one to a tolerable state of efficiency as a press feeder or bookkeeper, he would “blow,” throwing that extra work onto me, until another could be secured and “broken in,” only to repeat the performance in a few months. Every summer season, especially, became a nightmare along this line.

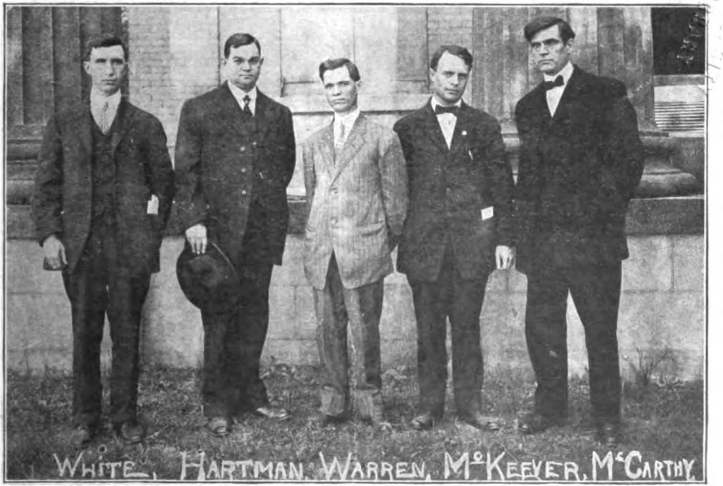

Finally, the question of moving to a larger city, which had always been up for consideration, asserted itself as imperative. Conditions last winter seemed favorable, and after investigating Chicago and Cleveland, the latter city was chosen as the new location for our printing plant and paper. As most of our readers know, the move was made in April of this year. At the same time, we secured the services of Fellow Worker Earl F. Moore, as secretary and general sub and literature promoter; and Fellow Worker Geo. Spangle, a first class printer. Their work has been invaluable, and with that of Fellow Workers Horn and Glover in the mechanical department, has gone far towards solving the problem of efficiency. But expenses have materially increased, and the financial handicap remains, as menacing, if not more so, than ever. It can be overcome very quickly, with a little more active work for the press, on the part of locals and individual supporters. The additional amount required on our monthly income is not large, and would entail no sacrifice on the part of our readers. Every I.W.W. local should have at least one good sub hustler, and see that he keeps busy. Every local should have a live literature agent, or committee, and see that a supply of literature is always on hand. Let us know what your needs are in the way of new literature, and help us financially to supply the same. If you have any job printing that need not be done in a hurry, send it in. An occasional donation, at times when strikes or defense are not demanding your entire attention, would also. help.

The field for I.W.W. literature is immense. This I.W.W. Publishing Bureau is the first serious attempt of the organization to specialize on the task of supplying that literature. In spite of the handicaps above outlined, we have really done considerable in the three years we have been working to that end. More than 100,000 pamphlets have been printed and distributed, besides those of other publishers handled through the Bureau. More than 1,000,000 leaflets have been scattered about the country among the slaves of all industries. Much of this literature has been placed on file in reading rooms and libraries, and read by many more workers than the number sold. The same is true of Solidarity, also. We have, I believe, more than justified our existence, and the struggle necessary to maintain it.

While this narrative is necessarily incomplete, it was not intended as a minute record of events in the history of this journalistic venture. I have only tried to portray the most salient features of our struggle, dealing more in detail with the early than with the later events. The future lies before us. What it will be, we cannot say. That depends very largely upon YOU WHO READ THIS STORY. If you believe this work of revolutionary education is worth while, and want to help more than you have done in the past, you will find opportunities close at hand. The men who have piloted Solidarity through the stormy seas of adversity, are JUST AVERAGE MEN. None is a genius. None has cared for the limelight for himself, at the expense of his fellow workers. They are just “Jimmy Higginses,” workers imbued with the revolutionary purpose of helping to unite the working class for the overthrow of capitalism and the planting of a new society in its stead. B. H. WILLIAMS.

Note: The New Castle Free Press recently passed out of existence. After having received thousands of dollars in defense funds,” on stock certificates and other loans, besides doing flourishing business in advertising and job printing after changing editors and managers a dozen or more times in two years, and spending all the aforesaid money besides contracting several thousands of dollars debts, it finally went into bankruptcy and later passed in its checks. This might be considered a case of “poetic justice” were it not for the fact that the real harm falls upon the labor movement at large.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1914/v04n52-w205-jan-03-1914-solidarity-texas.pdf