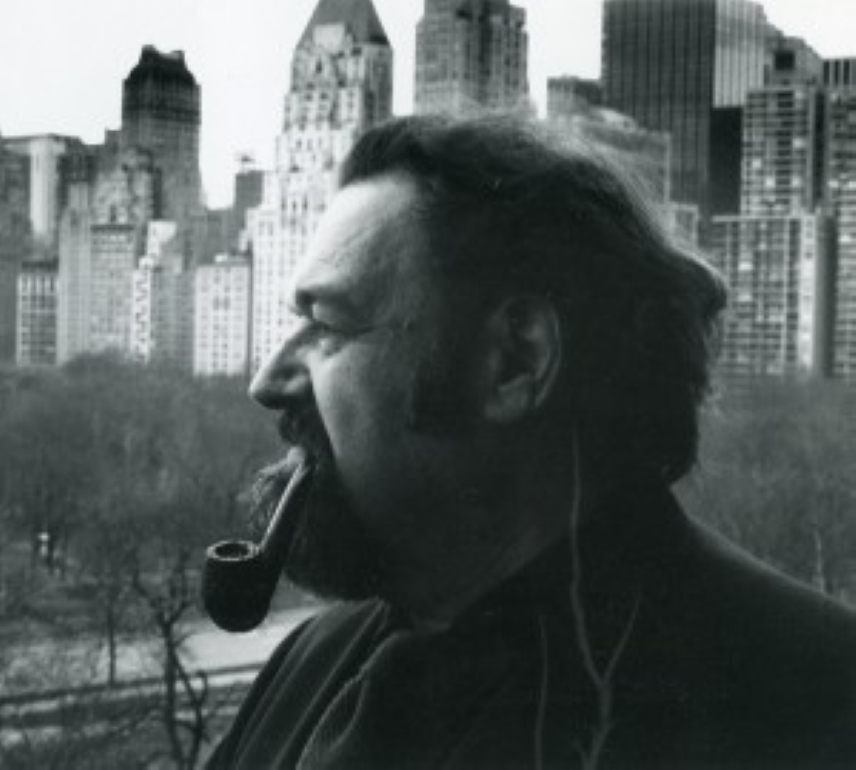

Harry Magdoff whose later editorship of Monthly Review had a profound impact on student radicals of the New Left, is here a 20-year-old student radical at City College of New York defending Marx fifty years after his death. Magdoff was then a leader of the C.P.-aligned National Student League and editor of its first paper, Student Review. Magdoff died in 2006.

‘Karl Marx: Fifty Years After’ by Harry Magdoff from Student Review. Vol 2 No. 5. March, 1933.

MARCH 14 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the M death of Marx. This name together with that of Lenin is full of meaning to millions of oppressed and exploited peoples all over the world. Particularly today when we are suffering from a devastating industrial and financial crisis, does the name of Marx have renewed meaning. Wages slashed, banks crashing, seventeen million unemployed, imperialist war in China and Latin America, preparations for further wars going feverishly ahead, retrenchment in education, misery, poverty, and degradation—this is what the ruling class offers us as a way out of the crisis. No wonder then that the oppressed masses of all countries are looking to a revolutionary way out, the Marxian one. But on the path to learn the true meaning of the Marxian way out these masses are delayed and diverted by demagogy and “scientific” chicanery.

Together with Hoover’s learned predictions of “prosperity in sixty days,” campaigns of apple-selling and “Buy American” slogans, we are, in turn, deluged by so-called scientific panaceas. Among the more modern cure-alls, we find Technocracy. The Technocrats conceived the prime evil of capitalism to be the so-called price system. Their resultant ideology, however, springs from a superficial analysis of capitalism. It is true that under certain conditions prices tend to rise and capitalists will increase production. It follows that as prices fall, production will likewise decrease. It would be ridiculous to think that a rise or fall in prices cause a change in the amount of production. Under specified conditions, high prices signify booming profits, and capital, therefore, will be invested in such industries which promise lucrative return. Should these prices fall, it will mean less profits, necessitating a decline in production. The basic regulator of production in a capitalist society is the search for profit. The Technocrats perceived the flaw of capitalism in distribution, rather than in production. They did not see that the mode of distribution relies solely and is minutely interrelated with production.

Still more essential to the Technocrat scheme of things is that they desire the technicians and scientist to control the economic system. How are they going to gain control? They deny the use of political methods. Still the question may be asked: how does the ruling class keep itself in power? How are the property relations of capitalism sanctified and controlled? They are manipulated by the state in the form of law, courts, judges, police and the army. Denying political methods of attaining control and supplying no alternative, signifies the fact that the Technocrats base their credo and cure upon ephemeral utopian grounds.

Following the astounding phenomena of rapid economic progress in the Soviet Union co-eval with the rest of the economic world suffering from a most devastating collapse, our academicians started to plan puissant reconstruction. The planners of a re-organized society were hampered, however, by their inability to transcend the pale of capitalism. They stressed the fact that capitalism must be stringently planned, and in the planning alone lay the well-being of the future economic state. Their method of intellectual bushwacking in dealing with such phenomena evolves in abstractions of the most flimsy texture. It must be borne in mind that the crux of capitalist economy is the accrual of profit. Should an industry be planned, and should it be found that the people be benefited if the rentier class do not receive increasing profits, will the rulers invested with political power, i.e., the armed force of the state, calmly allow seceding industry to evade their scepteral power? To imagine the entire ruling class good-naturedly relinquishing their profits for the benefit of society as a whole, is a wild conjectural conclusion. Let us imagine, for the moment, that industry is controlled for the capitalists in their interests. The profits of the entrepreneur can only be realized by further exploitation of the workers. This is done by lengthening the working-day, wage-cuts, speed-up, and improved technique. Karl Marx in his theory of surplus value, demonstrates how profit is derived from unpaid labor. The worker produces his wages in a portion of the working day. The surplus labor time is the surplus value, part of which is realized in the industrialist’s profits. In order to increase the relative surplus value, a super-complicated and ultra-efficient machinery is introduced so that a larger portion of the working day is devoted to the production of surplus value. We are therefore confronted with the twofold development in search for profits: the lowering of the standard of the worker and the increased production as a result of the newly developed technique to increase the relative surplus value. And exactly this development, which is a result of the profit motive, is the cause of crises. Therefore even in a planned capitalist society we would have crises if the profit motive is not abolished. We certainly won’t abolish the profit motive by praying for it.

In opposition to these illusory and fragile theories and plans we have the Marxian system. Marx applied his philosophy of dialectic materialism to the problem of evolution of societies. He indicated that historical development is determined by the evolution of the productive forces.

“In the social production of the means of life, human beings enter into definite and necessary relations which are independent of their will—production relations which correspond to a definite stage of the development of their productive forces.” (Preface to the Critique of Political Economy.)

We have shown in our discussion how the continual struggle for profits causes the development of the technique of production, the productive forces. We find therefore, the development of mass production. The mass of workers grow. The working class is intricately related to production. The owners of the means of production are divorced from the process of production. The process of production becomes socialized. Simultaneously there arises a fierce combat in the form of competition among the capitalists themselves. Ownership evolves in monopoly. A class of superfluous owners grow together with the development of large-scale and socialized production.

“Capitalist monopoly becomes a fetter upon the method of production which has flourished with it and under it. The centralization of the means of production and the socialization of labor reach a point where they prove incompatible with their capitalist husk. This bursts asunder. The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.” (Capital, Vol. I.)

This is the basic contradiction of capitalism, that between socialized production and capitalist appropriation, a contradiction which expresses itself most clearly during periods of crises. This contradiction expresses itself in the antagonism between the capitalist class and the propertyless producers. This class struggle is the clue to the way out of the capitalist crisis. The contradictions of the capitalist society are inherent in its very structure. The paralyzed capitalist class can no longer control the productive forces which it has produced. Therefore a revolutionary upheaval of capitalist productive relation is the only way out. This Marx demonstrated by an analysis of the structure of capitalist society and its laws of development (Capital). The only class capable of accomplishing this goal is the revolutionary working class. Hence those students who realize that the only solution of the crisis is the revolutionary Marxian one, can aid and participate in this revolutionary exodus only by lending their support as an ally of the working class.

The class struggle of the proletariat assumes a political form. The aim of this political struggle is the forceful overthrow of the capitalist state.

“It is only in an order of things in which there will be no longer classes or class antagonism that social evolution will cease to be political revolutions. Until then, on the eve of each general reconstruction of society, the last word of social science will ever be, ‘Combat or death; bloody struggle or extinction, It is thus that the question is irresistibly put.’ (George Sand)” (Karl Marx, Poverty of Philosophy)

After the overthrow of the capitalist state the proletariat and its allies under the leadership of a Marxist political party assumes control under what is termed a proletarian dictatorship.

“Between capitalist and communist society, there lies a period of revolutionary transformation from the former to the latter. A stage of political transition corresponds to this period, and the State during this period can be no other than the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.” (Karl Marx, Criticism of the Gotha Program.)

In a letter to Weydemeyer (1852) he further declared clearly,

“As far as I am concerned, I cannot claim to have discovered the existence of classes in modern society with all the strife against one another. Middle class historians long ago described the evolution of the class struggle and political economists showed the physiology of classes. I have added a new contribution with the following propositions: first, that the existence of classes is bound up with certain phases of material production; second, that the class struggle leads inevitably to the dictatorship of the proletariat; third, that this dictatorship is but a transition to the abolition of all classes and to the creation of a society of free and equal beings.”

The role of the proletarian dictatorship is the abolition of the capitalist class and the creation of a classless, planned society. The socialized productive forces are controlled socially for use and not for profit…in short, a socialist society.

It is my contention, and facts bear me out, that the adherents of Marx today are the Communist International and the Communist parties in each countries, all of which carry into practise the teachings and principles of Karl Marx. The Communist International accurately foresaw the present crisis, its extent and specific characteristics. While our learned economists and professors spoke of “prosperity around the corner,’ “a minor depression,” and a multitude of other insignificant phrases, the Communist International pointed out that this crisis marked the end of capitalist stabilization and indicated the financial collapse which we are witnessing today. The Communist parties form the conscious vanguard of the working class and its allies in the revolutionary struggle for the overthrow of capitalism and the building of Socialism. This task is being accomplished in the Soviet Union.

Marxism is not dogmatic. It is a creative system of development. In this respect it is most essential to point to Lenin as the greatest exponent of Marxism in the twentieth century. Capitalism developed into a new epoch, the epoch of Imperialism. Lenin’s teaching represents the Marxism of Imperialism. (See Summer, 1932 issue of Student Review.) Lenin developed in further detail the theory and practise of the proletarian revolution. Through his brilliant understanding and application of the dialectic materialism of Marx to concrete problems confronting the proletarian movement Lenin developed this philosophy. In nearly every field that Marx touched upon, Lenin made some significant contributions. Therefore, the study of Marxism today, in the epoch of Imperialism, necessitates an understanding and study of Leninism,

We may add that the very essence of Marxism is the unity of theory and practice. Marx personally participated in the organization of the International Workingmen’s Association (the First International), and became its leader and guiding spirit. An understanding of the Marxian system is incomplete unless accompanied with an active participation in the working class struggle to overthrow the capitalist system.

No wonder, then, that in our classrooms and text-books Marx is either completely ignored or falsified and “refuted” in a very petty fashion. Interesting in this respect is Professor Laski’s article “Marxism After Fifty Years” in the March issue of Current History. He asks,

“Why should principles the refutation of which is the ordinary stock-in-trade of the academic social philosopher secure an immortality denied to Comte and Saint-Simon, to Proudhon and Fourier and John Stuart Mill?” (My emphasis—H. M.)

But Professor Laski presents an amazing “contradiction.” On the basis of these principles “the refutation of which ‘is part of the ordinary stock-in-trade of the academic social philosopher,’ Marx developed laws of society which are real and accurate. Laski later states,

“But his title to eminence does not rest upon the Russian fulfillment alone. The crisis through which capitalist democracy is passing at the present time accords with the forecast he made. The power to produce without a parallel ability to distribute, the growth of unemployment, the increasing severity of economic crises, the conflicts of economic nationalism with their resolution by wars which issue into civil violence, the inability of parliamentary democracy to satisfy the demands of the masses [as if Fascism in Italy and now in Germany satisfy the demands of the masses! H.M.], their consequent sense of its importance to meet their problems, all these he marvelously foresaw. His insight enabled him to realize that the test of capitalist society was its ability to be continuously expanding, that once it became involved in its own contradictions it would go the way of all previous systems which failed to battle with, to adapt themselves to, their special environment.”

Our professors cannot understand this phenomena. They are limited in their thinking to a defense and apology for the capitalistic system. They therefore very weakly “refute” and primarily distort Marxism, the revolutionary philosophy of the working class. When confronted with the acid test of reality and experience as a proof of Marx’s teachings, our professors, or as Lenin called them, “the scientific salesmen of the capitalistic system,’ are amazed and attempt to find some more “‘fallacies.” Some adopt a much more subtle method. They claim that they are Marxists, pose as friends of Marxism. Then they revise Marx’s doctrines transforming it usually according to contemporary bourgeois thought. Marxism developed in a struggle against these revisionists (Bernstein, Duhring, Kautsky, etc.). Among political groups today we find the Socialist Party since the crisis mouthing Marxian phrases. Yet in their political program and philosophy we find a basic revision of Marxism. In particular do they revise the Marxian theory of the state and class struggle. In academic circles we are treated with the revisionism of Professor Sidney Hook. He attempts a transformation of the dialectic materialism of Marx to the pragmatism of Dewey, thereby revising Marx. (See Communist of January, February, March, 1933.)

To learn Marxism we must go to the original. We must study Marx and the true Marxists. But as we have pointed out above, it is not enough to study Marx, for a true understanding of Marxism leads to action. And through the experience and training we receive from action we will be better able to understand and apply Marxism.

Emerging from the 1931 free speech struggle at City College of New York, the National Student League was founded in early 1932 during a rising student movement by Communist Party activists. The N.S.L. organized from High School on and would be the main C.P.-led student organization through the early 1930s. Publishing ‘Student Review’, the League grew to thousands of members and had a focus on anti-imperialism/anti-militarism, student welfare, workers’ organizing, and free speech. Eventually with the Popular Front the N.S.L. would merge with its main competitor, the Socialist Party’s Student League for Industrial Democracy in 1935 to form the American Student Union.

PDF of original issue: https://archive.org/download/student-review_1933-03_2_5/student-review_1933-03_2_5.pdf