A superlative Sunday read, this journey with Michael Gold through the mining towns of southwestern Pennsylvania and deep into the social history of the U.S. class struggle.

‘Palm Sunday in the Coal Fields’ by Michael Gold from The Liberator. Vol. 5 No. 5. May, 1922.

EXCEPT for attending a meeting of the Central Labor union in Pittsburgh, and drinking, in a barroom decorated with the Soviet arms, seidels of a wonderful drink that really tasted like beer, smelt like it, and had all the other ancient virtues of beer, I saw little of the labor soul of the city–that soul which is present in every city in every nation on the globe–(though outsiders never see it and come away depressed). Two and a half hours outside of Pittsburgh, however, I at last found myself in the heart of the great coal strike.

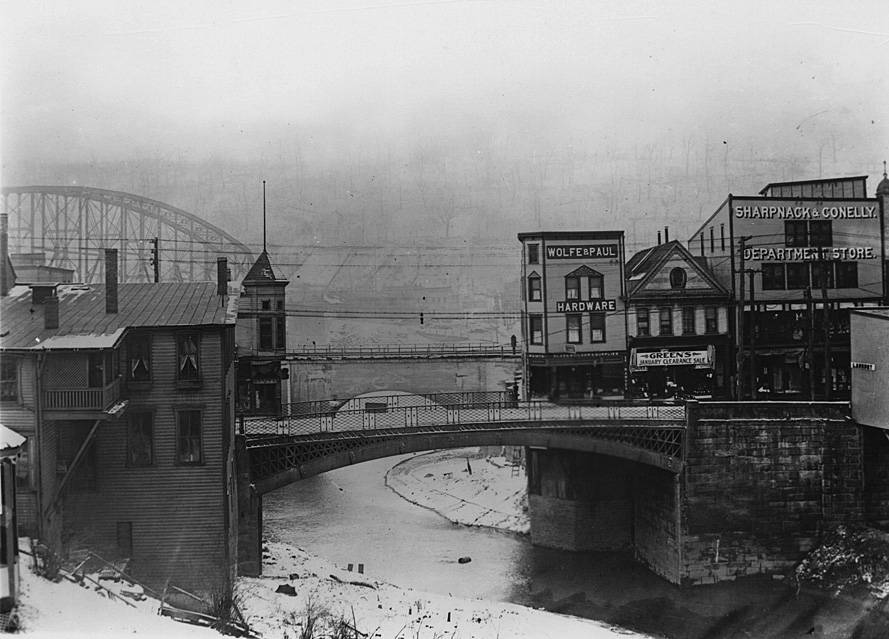

I had wandered into Brownsville, a town of 10,000 inhabitants, which is the centre of the coke industry and of the coal mines that feed this industry.

They were talking steel here, I found. Steel has to be made with coke, and coke is a kind of bituminous coal that is cooked in ovens until it is a gray, light porous lump of matter, something like lava. All of the coke used in the steel mills about Pittsburgh comes from the Brownsville and Connellsville fields. They are probably the most important coal fields in America for that reason, and for the past thirty years Frick and his fellow-Christians had seen that no union got a foothold here, using the blacklist, the blackjack, the assassin’s revolver and other New Testament methods of persuasion to accomplish this. There had been no union held here since Frick and his comrades in Christ had shot the Knights of Labor out of existence in 1894.

Everyone, bosses and union officials alike, had imagined that this region would forever be the peaceful home of starvation wages, the open shop, and deputy-sheriff Americanism. Secretary Hoover had depended on this, too, and he had cheered the coal barons by announcing at the opening of the miners’ strike that there was a surplus of four months’ coal supply on hand, and that the miners would be starved into submission at the end of that time. Hoover had reasoned, in his New Republican way, that the Brownsville region would go on scabbing, as in the past. But a great miracle had happened. There had been a wonderful spontaneous movement of the masses; 28,000 miners in this sector, and as many more in the Connellsville area, had joined the union; everyday hundreds more were downing tools and joining the strike. As a result, three big steel plants had already been forced to shut down for want of coke, the Pittsburgh papers said. Hoover’s helpful little capitalistic estimate discouraged no one any longer; it was proven false as the complexion of a chorus girl, or the heart of a Wilson liberal; it was as dead, in the light of events, as a herring or Pharaoh’s scented, mouldy mummy.

The strike in the non-union fields was like America’s entry into the war; it spelt victory, sooner or later, for all the miners of the nation. By good fortune I had chanced into this region, the most important strategic point in the great fight that had begun on April 1st to save the miners’ union from destruction.

Hundreds of miners in their Sunday clothes were lounging about Brownsville’s main street as I came into the town. They were big, brawny, self-contained men, of all the races in the world, and they stood about on the sidewalks in the yellow sunlight of the warm spring afternoon, smoking, chewing, and talking in quiet tones of the strike.

The stores were all open, and women moved in and out of them, like bees to and from a comb. The river and the rusty, rugged hills rising from its bank could be seen against the blue deep sky. Spring was in the air; there was in this town of lounging men the spring atmosphere of freedom, of holiday and of strange, unspoken unrest. Something silent and great was happening unseen beneath the mould of all the ploughed fields; and something was happening here. Grim-lipped big men walked up and down the sidewalks, with badges pinned on their coats, and police clubs swinging from their hands. They were keeping law and order. And the miners sat about the restaurants and the ice-cream parlors, and stood about the streets and thought and argued and talked to each other. Something great was happening.

The union hall was on the other side of the river, in an old murky frame building that had still the sign of a defunct co-operative store written across its face. In the long, dark hall on the first floor the organizers were seated at a table, conferring with the committee of men from different mines who poured in all the afternoon. They seemed to arrive from everywhere; one after another they announced the mines they came from, and as the names were repeated exultantly around the hall, one got the feeling as if the whole state of Pennsylvania was stopping work. It was a gay feeling.

“The crowd at the Lambert mine struck this morning,” a huge, slow-moving American in blue overalls announced diffidently, almost as if he did not care. “The whole bunch is out; and I guess you’d better send us an organizer, and tell us how to get fixed for a local charter.”

Then one of the organizers would take the name and location of the mine, and would arrange for a meeting the next afternoon. An international organizer for the United Mine Workers named William Feeney was in charge of the campaign in this section. He sat at the table near a dingy window, a frail, patient-looking man with a long Irish upper lip and friendly blue Irish eyes, who moved calmly and deliberately about this business, and seemed like the executive of some big corporation in his quiet business suit, white collar and natty bow tie. I had heard about him before I had come here; Feeney, I was told, had been one of the most daring organizers in the steel strike; he was considered a little conservative in his views, but everyone agreed loudly that “Feeney had guts;” and everyone said that he was honest and loyal, and would fight all the chariots of hell for the miners’ union, which was his religion and life.

The miners’ union is the religion of every worker in this district. In New York one gets the illusion that the class struggle is an intellectual concept that one can argue about, take or let alone. In these mining districts it is a living reality, and one can no more dodge it than one can escape from the weather. The miners’ union is part of the trees and the hills, the sky and the air of this landscape. It grew here, out of the needs and dangers of the miners’ lives. They suffered and struggled, and then a union was formed; and through it they found some relief. They know that the union is their only defence; for forty years fathers have been handing down its precepts to their sons in this region, and no one questions that the union is necessary or unnecessary; it is there; it must be there, so long as the boss is there.

I talked to some of the other organizers who were helping Feeney in the work. One of them, Bill Henderson, a short, vigorous bantam of a man, compact as a mainspring, and with the alert light of a born fighter snapping in his eyes, told me about the meeting he had held yesterday at the Revere mine.

“I organized five hundred men up there,” he said, his eyes burning. “It was the proudest moment of my life, too, and I’ll tell you why. Thirty years ago my daddy was working in that mine, and he went out when the Knights of Labor called their big strike in ’94. We lived in a tent up on the hillside, our family; I was only a wee boy, but I remember it all. I remember that we had mighty little to eat for a long time, and I remember my mother crying over us one night when she thought we were all asleep. And I remember that my daddy was blacklisted after the strike was lost, and how we wandered on from town to town till we found a place where they didn’t know him. I tell you I was proud to go back there and organize those 500 men. I wish my daddy were alive; he’d have been proud, too.”

The whole countryside was filled with stories of this Knights of Labor strike of thirty years ago. Everywhere I found miners who remembered it vividly, and who remembered all the other battles the region had been through. Other countrysides have their folklore and mythology, but in the nation of the miners there are only stories and histories of the wars for the union.

In the hall there was a lean, sombre-eyed miner in neat clothes, named Frank Gaynor, an American of Irish-Dutch descent and about forty-five years old. He looked as if he were a successful small-town merchant, but he was out on strike down at Roscoe, and had come here to volunteer in the work of organizing the non-union mines. He, too, told me some of the traditions of this region.

Gaynor’s father had died when he was six years old, and at nine the boy went down into the mines to work with his grandfather, an ardent member of the Knights of Labor. His grandfather had been a miner since his own ninth year in this world, and could remember the days when there were no mule-carts or steam-cars in the mines, and the men had to transport the coal they had mined with wheelbarrows to the pit-mouth.

Gaynor was seventeen years old, and had graduated to pickwork when the big strike came in ’94. This Monongahela Valley was aflame with it, and all around Brownsville meetings were held daily, the organizers walking from place to place because they had not the fare to ride. Most of the mines emptied their workers into the union, and in this section only Star Junction, or Stickle Hollow as it was then called, had not struck. Organizers were beaten up and chased out of the region there, and finally the miners decided to march on it en masse. These miners’ parades are another tradition with them; the gesture of men instinctively militant and personally loyal to each other in an emergency. Five thousand men were in line that day, Gaynor said; some had walked ten and twelve miles to the assembling place; it was spring, and they were all hot and tired when they reached Stickle Hollow.

Suddenly, from behind a clump of bushes in the road near the mines, a band of deputy sheriffs fired on the peaceful, unsuspecting, unarmed regiment of miners. Seventeen of them were killed; many more wounded.

“It was awful to see our fellows lying there in their blood,” said Gaynor; “good fellows, the best in the world. They were killed for daring to strike. I was young then, and the sight made a lifelong impression on me. It taught me a lesson I’ve never forgotten. No one has forgotten it around that region. The kids hear the story on their daddy’s ‘knee; they drink in its lesson with their mother’s milk. The coal operators and their gunmen have been the best agitators for a union I know.”

The coal operators were still continuing this form of agitation. The day previous there had been a miners’ march through Masontown, a place about twelve miles from Brownsville. A squadron of members of the State Constabulary (Cossacks they are called by the workers of Pennsylvania) had suddenly appeared and ridden their horses full tilt into the parade. One miner had had his leg broken; about thirty others had been injured; there had been quite a lot of loyal union men made in the brief, uneven scuffle.

In the hall there was another miner who had gone through years of such struggles. He was Jasper Rager, about 70 years old, a miner since his childhood, but still brawny and self-reliant. He stood there quietly, in his flannel shirt and hob-nailed boots, a stalwart veteran with a white military moustache and leathery face spotted with blue powder marks, the seal of dangerous days that is on all miners’ faces. Simply, casually, for miners never whine, he told me the most recent story of the methods coal operators use to make attractive the open shop and the American plan.

It was nothing very big; no one killed or wounded; merely that old Rager had answered the strike call, and had persuaded a few non-union men to come along; he was spotted, and the company had shut off the water in his company-owned house, and also had refused to sell him any more coal. He had two children sick with pneumonia, and his wife was sick of some fever; he was nursing all three at the time; but the company shut off his water and refused him coal; that is the way the coal bosses teach their men to be loyal Americans.

I heard many other such stories. There are thousands of them; they are the reality of the labor movement; they are the reasons why thousands of Fourth of July speeches corporation-owned Congressmen, tons of Americanization literature written by lecherous, booze-soaked press agents and paid for by murderous bosses, miles of editorials by prostitute newspapermen and oceans of oily lies flowing from the ministerial sewers can never divert Labor from the path on which its feet have been set by history. Workingmen know the facts about the class struggle; the facts have been shot into them with gunmen’s bullets, beaten into them with Cossacks’ clubs; they remember these facts; and forget soon enough, thank God, the lessons American social service has tried to teach them.

In all the newspapers this great coal strike was now being discussed. Everyone knew the academic questions involved in the situation. The miners and the bosses had an agreement that expired on April 1st, when it was provided that they meet to make another wage agreement for the following two years. The operators had refused to renew the argument. They wanted to make local settlements in each of the separate districts. They wanted to abolish the check-off; they wanted to cut wages; they wanted other concessions.

That was the faint, far-off newspaper story millions of Americans read, half-understanding, half-irritated because the miners and the operators could not iron out these tiny quarrels that after all amounted to nothing.

But they amounted to everything in the world for these men in this Brownsville union headquarters. Here were the men who made the strike a reality. These miners “knew” the facts. Big, strong men in overalls, jumpers, flannel shirts, hob-nailed boots, men of ten or twelve races, Lithuanians, Poles, Italians, Austrians, Croatians, Slavs, Negroes, Welsh, Irish, British and Americans–bold men, men who faced death every day in the hot, dripping, airless mines; men with mutilated hands, powder-marked faces; these men had formed a union to get them a living wage for their wives and children, and to protect them against the gunman, the thug and the spy. They had fought for that union, and their fathers had fought before them. The union was their self-respect; it was their children’s bread; and now the bosses were making a fierce new attempt to smash it.

I traveled about for several days with organizers in the non-union fields.

On Palm Sunday I went with Bill Henderson and a Pole and a Czecho-Slovak organizer to the mining camp of Bowood.

It was a warm, golden day, rich with spring odors and spring sunlight. In Masontown, where we left the car-line and got into a wild, young, untamed Ford for the five-mile ride inland, the churches were emptying, and miners and their women-folk dressed in their finest were moving leisurely up the main street. They were all carrying palms, the sacred palms with which the Jews hailed Jesus on that sunny, holy day when he passed through them on his ass on the way up to Jerusalem.

It was in Masontown, a few days before, that the state troopers had charged into the parade of miners, and had injured thirty of them. We saw one of the troopers resting his horse before a church and sitting quietly as if in meditation. He was a lusty young chap, with ruddy cheeks and broad shoulders and big muscles under his dark-green uniform; as fine an animal as the splendid horse he was straddling.

“The dirty Cossack!” the Polish organizer muttered, scowling darkly. “The damn trouble-maker; the damn murderer!”

Every labor man in the State of Pennsylvania hates the State troopers. These “Cossacks” are the most highly paid and best trained set of assassins of labor unionism in this wide country. They possess military efficiency–they crack heads skillfully, and trample women and children without a blunder in technique. Wherever they come they bring riot and death. They seem to love their jobs, these young men; it is more than the high pay that makes them work so hard; they enjoy being Cossacks, as some men enjoy war with its legalized rapine and slaughter.

A crowd of men and boys swarmed into the road as we galloped up in the Ford before the grocery and butcher store at Bowood, where the meeting was to be held. I sat around on the porch and waited while the organizers talked over matters with the local committee.

The miners gathering around were of the same type I had seen everywhere in this region-men of ten or twelve races, big, stalwart men with the blue tattoo marks of powder and rock on their faces, and with fingers missing and fingers gnarled and twisted on their hands.

A small group of American miners was looking at a cartoon in a Philadelphia newspaper. It was the usual “non-partisan” thing that newspapers are so fond of printing in big strikes. It was called Passing the Buck, and showed the Coal Operators, the Banker, the Railroads, and the Coal Miner passing the buck of high coal prices to each other, while a figure dressed like Uncle Sam, and marked The Public, was standing beside a tiny heap of coal, scratching his head in bewilderment.

The miners sneered at this cartoon in their quiet way. “I’d like to meet this guy Public sometime,” drawled a tall young chap; “I’d jest like to kick his backside and see whether he’s real enough to feel it.”

A huge Hungarian miner with a flat nose, high cheekbones, and a chest like the bulge of a stove, was busy at another spot on the porch, explaining his views of life, liberty and happiness to a squat, brawny Austrian with thin, long moustache like a Mongol’s, who was sucking his pipe and listening, his derby back on his head.

The Hungarian was in roaring good spirits. He was dressed in a clean white shirt, collarless and coatless, and his beady little eyes beamed with delight.

“Me strike, sure!” he shouted, thumping himself on the chest with a fist hard and round as a sledge. “Me strike twelve times in last two years-me like strikes. Me strike in Mesaba range with I.W.W.–me strike with anyone. I say to the boys, Ah, g’wan and strike! Me live once under blanket in winter with my children–for strike! G’wan, boys, it’s summer now–me say put up tent in fields, go fishing, strike! The bosses are all no good! The bosses in our mine bought big searchlight–cost two million dollar–what for? Me load forty tons a day, and the boss’s gal she wears diamonds. What for?”

The mines in these non-union fields, some of them, had not been working for many months. I met on this porch a tall, self-possessed, middle-aged American miner, who spoke with a drawl, and who told me the most remarkable story I heard in this section. This man had ten children. And he had been out of work for the past fourteen months. On April 1st, when the union miners walked out, his mine opened up again, to scab on the rest of the country. The mine was soon rushed with orders.

This man and his comrades put in about a week’s work, and then they walked out on strike.

I will repeat this statement–The man and his comrades put in a week’s work, and then they walked out on strike. After fourteen months of idle–For the sake of a union. Ten children. Middle-aged and worn-looking; sad, brown, loyal, friendly eyes; square jaw, long nose, lanky figure in blue overalls, a torn black jacket, broken shoes. For the sake of a just cause.

“The whole family of us jest lived out in a tent all last summer,” he said. “My ole woman’s game, though it’s hard on her, more th’n me. Yes, I’ve been blacklisted in a few places, that’s what made it hard to connect up elsewhere. No, none of my kids was big enough to get into the army. I’d ‘a’ larruped them with a rawhide if they did–we’ll do all our fighting right here in Fayette county–there’s enough to go round. I fought a detective once–he put me into the hospital for five weeks, but say, he was laid up for nine! And once I saw the State Cossacks ride their horses over a bunch of miners’ kids that got in their way. Yes, I seen it; I seen them bleeding and crying. I’ll do my fighting at home.”

The meeting was held in the back yard. Henderson and the other two organizers stood on the steps leading up to the house, and the crowd of men and boys filled the yard. The soft wind was blowing. The smell of grass in the sun was everywhere. A little dog ran about the edges of the crowd and whined for attention. A rooster crowed; there was a cow chewing patiently on the grass of the next field. Bill Henderson’s militant words rang out like shot in this sylvan place, and the crowd pressed up and drank in every syllable. It was a proletarian holiday.

When Henderson called all who wanted to join the union to raise their hands, every hand went up, and every voice joined in the solemn oath which miners take when initiated into their union, an oath never to scab, never to betray a brother, never to desert.

I heard the oath repeated by about four thousand other miners later in the afternoon at Uniontown, where Bill Feeney and others spoke. It was thrilling to hear this mob of strong men repeat in deep, manly voices after him the litany and vow, sacred as the vow of the Athenian citizens, that symbolizes the miners’ attitude toward their union.

There had been not a single union meeting held in Uniontown for thirty years, I was told; this meeting was a red page in the miners’ history. I asked why it was that the non-union men were flocking so unanimously into the union now. The reason was simple. In the non-union fields Frick and the other operators were paying one-third of the wages paid in the other fields, under the union contract. The non-union miners had been starving on the job; they had no redress against bad supers and pit bosses; for years the operators had been teaching them the value of a union, and they had at last learned the bitter lesson.

The half million miners of the nation are not striking for any big positive end at the present moment; they are fighting to keep the union intact. It is the most serious fight they have ever been in; yet they are only on the defensive, in a negative position. They have no choice in the matter; but some day, when conditions are not stacked so badly against them, they are going to strike for bigger and more constructive ends. They are going to strike for nationalization of the mines, and control of production, slack work, technical improvements, wages, bosses and other matters by the miners themselves. They are going to strike for the ownership of their mines–of the mines where they live the greater part of their lives, where they mine coal.

John Brophy, president of District No. 2 of the United Mine Workers, is the leading spokesman for this larger program of the miners’ union. In the Brownsville district I found many miners who knew about this program, and were solidly behind it.

One was a lively, slangy, happy, scrappy young miner named Delbarre, an artist in living dressed in a battered derby hat, a ragged dingy suit, and a flannel shirt. Delbarre is president of the council of all the Brownsville unions; he stumps about on a wooden leg, and is called “Peggy” by everyone. Peggy Delbarre is one of the “radicals” in this district, but he is not the talky radical we know around New York. He has been a leader in all the union movements in this district; and he is simple, honest, unambitious and popular. And he works.

He has a rich sense of humor. “Say, kid,” he answered with his wide, homely grin when I asked how long he had been a miner, “say, guy, I was a miner when I was a spermatozoa playing around in my daddy’s insides. It’s in my blood.”

I went with Peggy Delbarre, Frank Gaynor, and a breezy, slangy young American miner, Louis Seignor, who was the son of Polish immigrants and spoke both languages fluently, on a long auto ride one day to Fairchance, where the men of seven or eight mines had walked out and were waiting to be formed into locals.

Peggy was a volunteer organizer, and so were the other two men in the car. On the ride they told me of the preliminary work that had been done to get the men to strike in the non-union fields.

A committee of a hundred volunteers had been formed in Brownsville Labor council, and these volunteers had taken the strike circulars into the non-union fields long before April 1st. They had tacked the circular on walls and houses in the towns, they had distributed them to miners on the “man-trips” into the mines, they had talked and pleaded and argued. Some of them had been beaten up, and run off the company property, but they had won, anyway. Their work had probably saved the whole miners’ union in this fight, for, as I have said, these non-union fields are probably the most important strategic points in the whole country. And they had brought the strike here; it is the work of such rank-and-filers, unrecorded and unrewarded, that maintains the labor organizations of this country.

Our first meeting was at Fairchance. Five or six hundred miners were waiting in the road near the general store as we drove up. It was another beautiful spring day.

We met in a small stuffy hall, the floor of which seemed to bend under the strain of this unusual mass. The miners stood with bare heads, and listened while Peggy Delbarre made his speech. He told them about the strike; he told them what the Mine Workers’ Union stood for; he warned them against using violence; he gave a few practical lessons in organization.

“And don’t forget we’re all Americans. I’m an American, though both my parents were French. Forget what these hundred percenters try to tell you; they’ve got no monopoly on this country; they were only the first to steal it away from the Indians. Don’t let racial differences stand in your way. Labor is a nation all its own, inside the other nation. Labor didn’t get any nearer the last Republican and Democratic conventions than cleaning the spittoons, but that doesn’t matter; we dig the coal for America, we’re the real Americans; we keep the works going; we’ve got the real power.”

He gave the men the union oath, and then they elected their president, secretary and treasurer. Louis Seinar spoke to them in Polish, and Gaynor made a fiery miners’ speech full of deep, real passion.

We had tire trouble on the road, and were two hours late in reaching another meeting in Croatian Hall, on the outskirts of Uniontown. It was coming dusk, but the miners had waited patiently there; not one had lost his faith that the organizers would fail to appear. These miners, too, were organized, and given the oath to repeat.

“They’re all jolly now; they feel as if they were going on a big picnic,” said Peggy. “Later, when things get hard, there’ll be a reaction, but most of ’em will stick anyway. That’s what unions are good for; they teach the workers solidarity and discipline.”

It was dark now. A few stars had lifted their silver faces to the world. The moon was appearing in the purple sky. We rushed up and down the steep roads, sharp as the inclines of a roller coaster at Coney Island. The wind beat against our faces, cool and laden with blossom perfume.

“Give her the gas,” someone shouted, and the car leaped forward and hummed along with the roar of an aeroplane. Peggy sat at the wheel and laughed and sang. The dark masses of trees fled by like defeated ghosts. We caught the glimpse of immense bouquets of peach and cherry blossoms in the gloom. It was great to be moving, to be alive. We were going somewhere. going somewhere. Life was going somewhere. The American labor movement was going somewhere. This miners’ strike would be won, and other strikes for greater ends would be won. Someday the miners would sit in the congress of workers that ruled America. Someday the men who were near to the sources of life, the men who were brave enough to make steel and mine coal, would be building a new civilization in America, a new art and culture, a new society. It would be a brave culture, a heroic culture for strong men and women, a culture near to the sources of life. It would move along in beauty under the stars, it would laugh and sing.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses which was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics ay a pivotal time in Left history. The writings by John Reed from and about the Russian Revolution were hugely influential in popularizing and explaining that events to U.S. workers and activists. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party and was sold to the Party by Eastman. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. The Liberator is an essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1922/05/v5n05-w50-may-1922-liberator-hr.pdf