Radical, later blacklisted, puppeteer and pioneer of stop-motion animation, Louis Bunin on taking Yosl Cutler’s satirical puppets to the masses in New York City.

‘Punch Goes Red: Revolutionary Puppets Take to the Streets’ by Louis Bunin from New Theatre. Vol. 1 No. 10. November, 1934.

ONCE upon a time a great artist was thrown in jail for making a puppet. This is not a fairy tale: Daumier was the artist. The puppet was called Ratapoil (Rat-Under-the-Skin). He had a long nervous body and face and a bristling Van Dyke beard, and he was an uncannily eloquent comment upon Louis Phillipe, then king of France. The Church disapproved. The State threw Daumier into jail. But the people throughout Europe, laughed and understood the name and the nature of the little puppet.

This is only one instance of the silliness of the great, and the power of puppets. For hundreds of years throughout Asia and Europe, the puppet has been and still is a mischievous national hero, always thumbing his nose at hypocrisy and stupidity and the foibles of the great ones, always surrounded by crowds eager for the comedy and tragedy of the funny little stuffed figures.

Yosel Cutler, one of the most skillful and famous puppeteers in the profession once made an anti-religious satire on the Hebrew play, The Dybbuk. A puppet spirit or Dybbuk lodged in the body of a puppet maiden, bobbing its head out from under her skirt to make its presence known to the audience. Two frantic rabbis tried to dis lodge it by means of religious hokus pokus. They were not successful. The puppet janitor solved their problem by having a puppet messenger boy appear and announce that he had a Western Union telegram for the Dybbuk. The Dybbuk forgot himself and popped out. The maiden lost the Dybbuk and the curtain closed on a happy ending.

It is the exclusive right and heritage of the puppet to be whoever the puppet master wishes him to be. In England he is known as “Punch”, in France as “Guignol”, in Germany as “Casper!”, in Italy as “Punchinello” or “Pinnochio” in Mexico as “Mamerte”, etc. But prior to the past ten years puppets were not widely used in America. (It is interesting to note that puppets were banned by the Church in New York state and the old law forbidding their use was repealed only last year.) When Meyer Levin and I opened a repertory Marionette Theatre in the old Relic House in Chicago some ten years ago, both the puppet (laced over the hands and fingers and operated from below) and the marionette (operated from above by strings and controllers) were unknown to the general public. Our Marionette Theatre posters announcing the presentation of George Kaiser’s play From Morn to Midnight aroused the curiosity and suspicion of the neighborhood. In recent years there has been a tremendous gain of interest and use of the Puppet and Marionette mediums. Today there are over two hundred listed professional groups, and hundreds of amateur groups in America. Poor “Punch” has been suffering the humiliation of appearing only in innocuous fairy tales and meaningless circus tricks on the American puppet stage. Now Puppet Punch has gone red. And we puppeteers who know the traditional role that Punch has played in public life and his unique power to spread solemn ideas clothed in burlesque and satire, also know that the new recruit, Punch, has entered the only sphere of activity in which he can exploit to the fullest extent his unusual powers. We see of course what a particularly valuable ally Punch can be in an illegal or semi- illegal movement. A troupe of ten puppets take two humans along to assist with voice and manipulation. The puppets agree to let the humans take all the responsibility for playing dates and transportation, for expenses and profits. And what an ideal acting company Puppets make! These keen, mischievous critics are privileged characters of the theatre world. It is almost impossible to heckle or hate them for their criticisms, for if you did their stage presence and peculiar expressions would not change one whit and you would gain nothing by it.

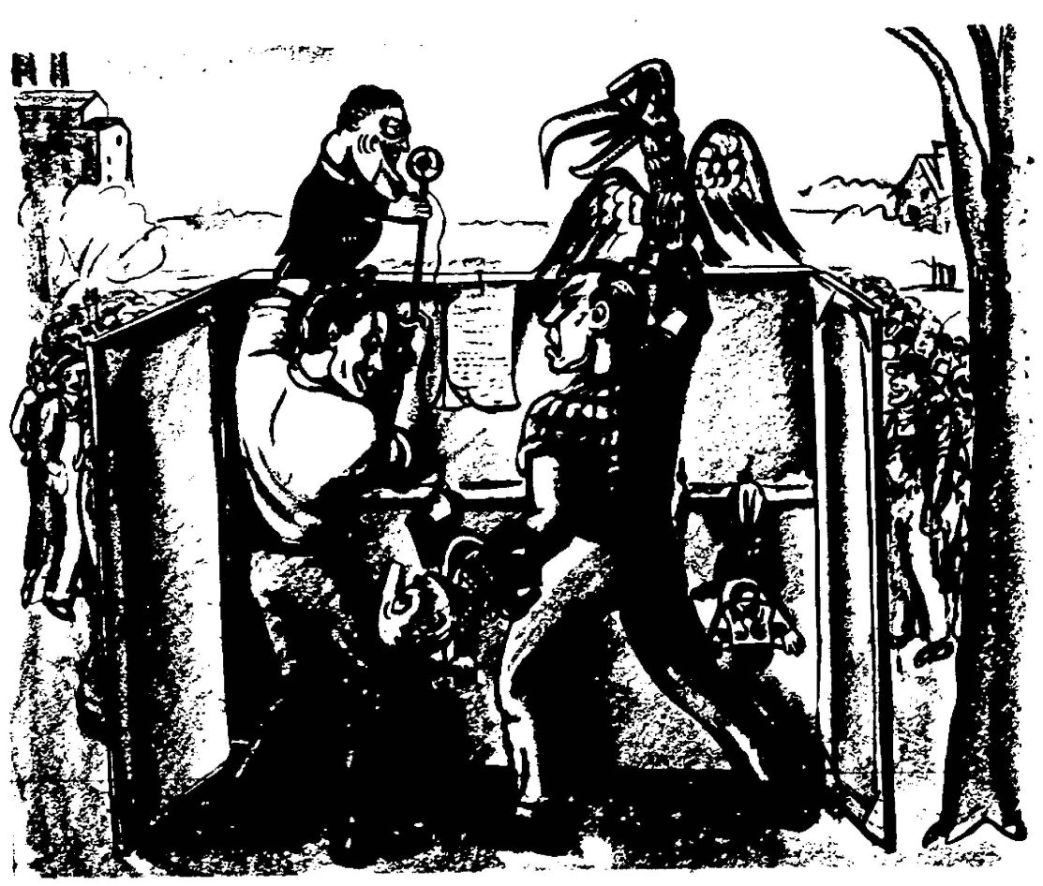

ON Tuesday, October 2nd, President Roosevelt, Madame Perkins and Bill Green addressed the workers on the corner of Tenth Street and Second Avenue, New York City. The Blue Eagle was there too, perched on F.D.’s shoulder. But they were not received with patriotic approval as shown in the newsreels. In fact they were enthusiastically booed, hissed and laughed at by a large and growing crowd. A puzzled cop stood by rubbing his thick neck in bewilderment. No police regulations covered this situation. Better go to the call box and find out what the Captain has to say. But look! Look what those guys are up to now! Roosevelt dancing with the Blue Eagle! Bill Green singing as he dances with Fanny Perkins:

“Oh Bill Green is my name Of strike-breaking fame I’m pretty damned clever At that little game.”

“Jesus”, the cop probably thought, “if they were four feet taller I’d call out the riot squad.” The fact that these nationally known figures were only two feet tall was not the only difference between them and their human counterparts in Washington. For these small stuffed figures were more real in self-revelation because the masks of their counterparts, their hypocrisy and demagogy, were removed and the people in the street saw them and the “raw deal” as they really are.

The Workers Laboratory Theatre has formed a separate puppet department since Puppet Punch and his whole puppet family have gone red. Now you will see them at outdoor meetings, on street corners, in union halls and workers clubs, amusing and at the same time educating the workers on the most important political and economic developments in America.

Here is a puppeteer’s modest vision of an effective revolutionary puppet show for an audience of share-croppers in Alabama. The actors are a skeleton and a vulture who profess in speech and pantomime a profound affection for Secretary of Agriculture Wallace and President Roosevelt. These two actors heap abuse on the third actor, Punch, a worker. The dialogue, simple and clear, must express perhaps in a fantastic manner the true conditions imposed on the share cropper audience by the A.A.A,, and must show through Punch the worker what they must do to overcome the A.A.A. oppression. Jack Shapiro wrote these lines for Punch:

“My stomach often rubs my spine

And now it’s started shrinking

And tho my head is made of wood

I’ve lately started thinking

I’ll see that everything is right

And if it’s not I’m going to fight

Let’s get together, use our night

And then we’ll give them hell.”

Punch is a gullible, tormented, passive worker at first. His acceptance of abuses is always exaggerated. Towards the last part of the skit, however, when he becomes conscious of the cause of the abuse, he overcomes it by speech and pantomime; that is, he drives the vulture off with the skeleton’s thigh bone, and in speech he actually tells the audience how to drive the A.A.A. vulture hovering over them.

IN dealing with the unemployment relief situation in New York the actors are Punch, an eloquent animated garbage can and a cop’s horse. All characters use a rich local dialect. Endless fantastic combinations, exciting because of their incongruity and remembered because of their effect on one’s imagination; are not only possible but an encouraging and inspiring challenge to the puppet-maker. The idea, always clear, is projected with the particular twist of the puppet technique. Clarity and imagination are the prime requisites of a successful puppet play.

The worker audiences have joyfully accepted the Blue Eagle Puppet, with his snapping beak and popping eyes and flapping wings. Oscar Saul wrote this dialogue for a new skit:

Bill Green

“Many workers are striking

Many complaints can be heard.”

Roosevelt

“If the workers are striking

We’ll give them the bird.”

Enter the bird, only to be driven away finally by “Punch” who punches the Blue Eagle off the puppet platform after a hard but determined fight. And, judging from the cheers that greeted this unexpected turn of events, the theatre of the puppeteers is indeed a sharp weapon in the class struggle.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v1n10-nov-1934-New-Theatre-NYPL-mfilm.pdf