Militant students, militant teachers. Chicago has a long, honorable history of working class education struggle. In April, 1933 students take the lead in a strike that will involve thousands of teachers marching in support. The full story below.

‘Chicago Students on Strike’ from Student Review (N.S.L.). Vol. 2 No. 7 May, 1933.

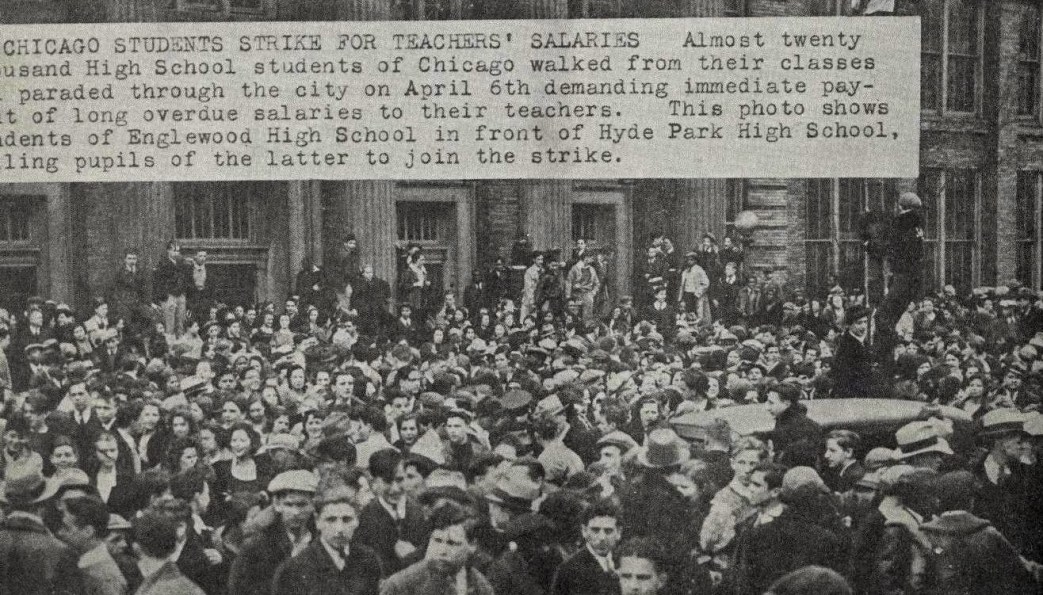

When 14,200 high school students struck in Chicago on April 6, the authorities spoke laughingly about “instruction,” appealing to parents for aid against the “bug of revolt, abetted by spring fever.” The strike was not a byproduct of spring, but one of the results of the teachers’ crisis, which has accumulated until there is now $28,000,000 in back pay owing to high school and elementary school teachers in Chicago alone.

The strike was orderly, but startling in its effects. At the Englewood and Calumet schools, a complete attendance of 10,000 students joined in the march. Most of the 3,100 students at Crane High School joined. Groups from the Normal College and a number of other high schools were added to the line of strikers, which marched to the home of Acting Mayor Corr, carrying banners, in favor of the teachers, proclaiming “GOOD SCHOOLS INCREASE INCOME, PREVENT CRIME, MAKE PROPERTY SAFE.” A demonstration held before the mayor’s home would have been even greater, except for the fact that many principals and teachers had appealed to the students not to strike, alleging that the action could not possibly help the teachers. The Chicago papers carried streamers, expressing amazement that a student strike could be so widespread. Two students at Crane Junior College, Rudolph Lapp, organizer for the National Student League at Crane, and Yetta Barshofsky, also a N.S.L. member, were expelled for addressing the students. They were later released and reinstated on probation. They said during questioning that they were liberals, but both denied being communists. A great amount of feeling had been stirred by the press and by the school authorities, who attempted the familiar side-step of blaming the affair on the “‘outside Communist agitators.”

The students were not alone in their protest. Large numbers of teachers telephoned requests to be put on the “sick” list, and twenty-five substitutes were sent to one school alone.

In the meantime, the school board and the municipal government were making “desperate” efforts to set a pay day. Governor Horner hurried to Chicago to confer with leading bankers at the First National Bank. A plan was formulated by which the bank should buy $1,700,000 worth of tax warrants, but no definite steps were taken.

On the following day, April 7, 10,000 students were still on strike. Police squads were sent to disperse one group of five hundred. Strikebreakers among the teachers were stationed at doors, refusing to allow the students to leave their classrooms when the firebell announcing the continuance of the strike was rung. At the Hyde Park High School, a bulletin board was set up after the principal suppressed a 100% strike, reporting the score of City Council vs. School Board as 12 to 12 in passing the buck. The Superintendent of Schools, William J. Bogan, returned from Springfield, where he had tried to get state funds, to threaten the leaders of the strike with $100 fines for interfering with the operation of the schools. Fining the students might sound suspiciously like a “desperate attempt to raise funds.”

A meeting held that night to call a halt to the strike heard Acting Mayor Corr protest that he had not implied that “any teacher was satisfied with conditions as they now exist.” Last spring stories were being circulated that college and high school teachers who had not been paid for months had been found sleeping on park benches and on the beach of Lake Michigan. But the Board of Education was, we must assume, biding its time. It took the student strike to arouse its efforts. Even then, they had attempted to issue a form of scrip which through speculation would rapidly decrease in value.

When Milton Raymer, a teacher in Tilden Technical High School, attempted to address the Board, a motion for adjournment was railroaded through by a trustee, on the grounds that she was late for tea. The teachers then held their meeting separately.

On the following day, the threats against the strikers began to be carried out. Wide publicity was given to the fact that several of them were members of the Young Communist League. The National Student League had given unqualified support to the strike, and other organizations, such as the Young People’s Socialist League, had also helped carry it through.

Announcements were then made that the $1,700,000 would be raised, as planned, by selling tax warrants to banks at a rate of 6 per cent interest for the bankers. It was explained that the Reconstruction Finance Corporation had refused to advance any money because “thousands of other school districts would immediately seek similar loans.” But the announcement of quick pay was contradicted on April 8, when the Board issued a statement saying that the payment would be postponed because of legal technicalities which were being introduced.

That day, the Young Worker Supplement, a broadside printed by the Young Communist League announced that the strike had been spreading steadily northward throughout the city, and that 30,000 students from elementary, junior, and senior high schools had joined in its support.

The National Student League issued a statement pledging assistance to all students in Chicago who were out on strike, and adding, “The students must continue the strike until the teachers get paid. Students must consolidate the strike movement in each school so that it can be spread. Do not listen to the principals who attempt to discourage the strike. You have shown your spirit and militancy. Continue it.”

In the meantime, the teachers were becoming active. On April 11, a demonstration of about 1,500 teachers took place in front of City Hall. They demanded an answer from President Taylor of the Board of Education. He gave it to them. He said that he was sorry, but nothing could be done. The Board, however, suggested that the schools be closed as a solution. A moratorium on education was the only proposal of the enlightened gentlemen.

And, that evening, Agnes Reynolds, a high school student and a member of the Young Communist League, was arrested for distributing strike literature. The literature stated the case in Chicago, the support and guidance of the Young Communist League, and was part of a leaflet distributed, calling for mass meetings and demonstrations. It pointed out to the teachers that since when they would get the $1,700,000, they would then have been paid for only the last seven days of June, 1932, they should continue their activities.

On April 15, more than 30,000 teachers, pupils and parents held a mile-long parade and demonstration. Milton Raymer spoke, and definitely militant note was sounded. Two days later an answer to the demonstration was given. The teachers were to become salesmen of the tax warrants, so that they might be paid! But the protest against this move could not be withstood, and a promise followed that they would be paid in cash their back pay for July, 1932.

The week presented a series of contradictions, with promise cancelling promise. After cash had been offered, the R.F.C. and the national authorities refused to supply the requested aid, so that Chicago knew that any cash on hand would be distributed as a palliative, not as a surety of any regular plan for the future.

During the last week, affairs have reached a higher level of tension. A group of teachers petitioned for the closing of schools unless they were given three months’ back pay; two days later, they were paid for last August. A demonstration was held before the Mayor’s home. It was clear that this state of affairs could not continue.

The situation reached another climax on April 24, when, according to the front page story in the New York Times, 5,000 teachers, wearing identifying armbands, stormed five of the biggest banks in the Loop. At some of the banks the steel doors were rolled shut to keep them out; but they held demonstrations just the same. At the City National Bank a delegation of 500 demanded that Dawes, who is chairman of the board of directors, answer their petition. After a half hour he came out, to tell them that he knew the situation as well as they did, and that the bank would invest in any securities it considered safe. Teachers who forced their way into a conference of the Governor, the Mayor, and the city and county officials on the tax situation were told by Governor Horner that “everyone that knows the situation is extremely concerned…not only concerned, but alarmed.” He declared that the only way to get the necessary money is through taxes on which the payments are already long over-due. The president of the Continental-Illinois National Bank said that the bank had a “new hope” that he could not reveal. And the president of the First National Bank said he agreed with the teachers that “something must be done not later than this coming Fall or there will be a breakdown of Municipal government. The solution lies in the collection of back taxes and putting teeth into the tax collection laws.”

Policemen, it was noticed, were not eager to stop or hinder the striking teachers. The police, the firemen, the doctors and other professional employees of the civil system have not been paid for many months, either. Members of the R.O.T.C. have been detailed to guard Calumet High School, a vigorous participant. This indicates very clearly the specific reactionary role of the R.O.T.C.

After the demonstration Orville J. Taylor, president of the Board of Education, announced that steps would be taken to close the schools within two or three weeks, instead of finishing the normal school term, which ends on June 23. The answer of the civil authorities has been to let the educational system break down and finally stop under financial pressure. The teachers are left unpaid—the students turned away with the school term incomplete and plans in session to curtail the academic course. Retrenchment in rural or small town districts is bad enough, but when one of the largest city school systems shatters, the mighty protest of students, teachers, and parents cannot be stifled by the misty condolences of Governor Horner. The assurances of General Dawes that the city can do nothing to pay its teachers must sound strange to Chicago, which has not yet forgotten how Dawes looted the R.F.C. to the tune of eighty millions last Spring.

If the Mayor’s estimate that a tenth of all the students and teachers in Chicago participated in the school strike is correct, then 200,000 people are involved in this gigantic bankruptcy. Extend this picture to the rest of the country. In the small towns and villages, where the teacher-student fighting organizations of protest have not yet been forged, retrenchment is causing terrific suffering. The educational system can only be propped up by waging a militant struggle against retrenchment, refusal to pay teachers’ salaries, the policy of moratoria on education, wherever these evils exist.

The National Student League will take the leadership in guarding the Chicago strike and ensuring that the struggle continues until the bankers and government officials find means to raise the money which the school system requires. Al) students must send letters, telegrams, or petitions to Orville Taylor, President of the Board of Education in Chicago, demanding that the Chicago teachers be paid immediately and in full,—to Henry Hagen, Principal of Crane Junior College, for the complete reinstatement of Rudolph Lapp and Yetta Barshefsky, —finally, to the Chicago Chief of Police for the unconditional release of Agnes Reynolds.

To punish students for “interfering in the school’s operation” is little short of ridiculous when one remembers that these gentlemen have attempted to run the educational system of Chicago on the basis of the philanthropy of the starved school teachers, and now announce that they have solved the problem by shutting down the schools.

The National Student League must carry on the struggle against retrenchment, against cutting the school term, against forcing the school teachers to support the educational system. This fight must be waged on the basis of the broadest possible united front between students and teachers, and it must be carried on in every locality where officials and wealthy taxpayers are attempting to solve the crisis at the expense of education.

Emerging from the 1931 free speech struggle at City College of New York, the National Student League was founded in early 1932 during a rising student movement by Communist Party activists. The N.S.L. organized from High School on and would be the main C.P.-led student organization through the early 1930s. Publishing ‘Student Review’, the League grew to thousands of members and had a focus on anti-imperialism/anti-militarism, student welfare, workers’ organizing, and free speech. Eventually with the Popular Front the N.S.L. would merge with its main competitor, the Socialist Party’s Student League for Industrial Democracy in 1935 to form the American Student Union.

PDF of original issue: https://archive.org/download/student-review_1933-05_2_7/student-review_1933-05_2_7.pdf