A fascinating account of Communist leading a strike, and building the Party, among tannery workers in the deeply conservative, but appropriately named, small upstate New York town of Gloversville. From the C.P. ‘s internal discussion bulletin.

‘Lessons of the Gloversville Tannery Strike’ by L. Lewis from Party Organizer. Vol. 7 No. 2. February, 1934.

THE successful strike of the 2,000 leather workers in Gloversville offers important lessons for our Party. This struggle was led and organized by Party members. Its victory was only possible because the line of the Open Letter was actually put into practice, although some serious mistakes were made at the beginning, which were corrected in time.

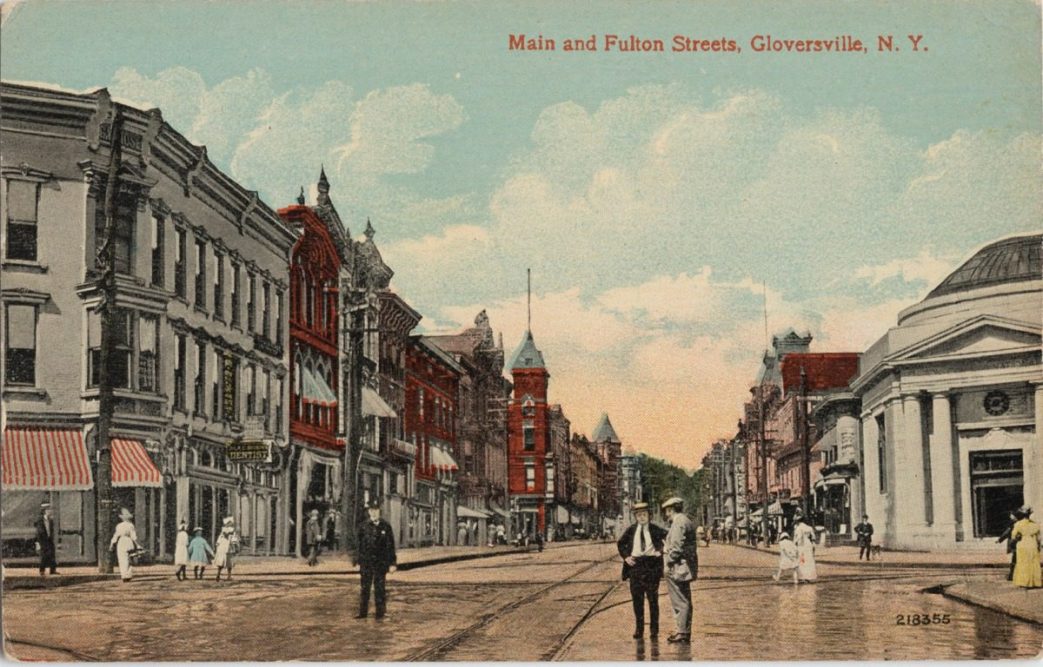

The tanning of leather is the basic industry in the glove cities. The 2,000 workers employed in the industry perform the fundamental operation in the manufacture of leather gloves. It therefore affects 8,000 other workers in that community. The tannery owners are the actual political and economic rulers of Fulton County, which is known as the nest of the K.K.K. and other forces of fascism.

There are only about 10 Negroes in the trade. There is a vicious discrimination against the Negroes. Nevertheless, this chauvinism was broken down during the struggle, and one Negro worker was elected to the union’s Executive Board.

The economic conditions of these workers were bad. Wages averaged around $10 a week with a constant fear of being fired and no organization whatsoever.

The party unit which “existed” was practically isolated from the leather and glove makers in spite of the resolutions and attempts made by the section leadership. Some of the leather workers belonged to an A.F. of L. union in 1920, but were sold out during a strike and the organizer broke the union by provoking discrimination of native workers against the Slovakian workers.

The glove manufacturing industry is organized into an A.F. of L. union with about 2,500 of the 4,000 in the trade. There was only one militant local union in the community, the Rabbit Dressers of the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union. These workers produce the skins for the fur-lined gloves in the county. This inspired a section of the glove industry, those cutting and making the fur linings, to seek organization for the improvement of their conditions. They looked up the N.T.W.I.U. local rather than the A.F. of L.

The fur workers were organized within one week and prepared for a strike. After four weeks of struggle, the 150 fur workers were victorious. They won a 50% increase in wages, union recognition, recognition of shop committees and equal division of work.

Although only 150 were involved in the strike (this is practically the lightest section of the glove industry), it had a tremendous effect on the leather workers. During the fur liners’ strike contacts with leather workers were established through a C.P. member, a native-born leather worker who has prestige among the workers.

Methods of Approach

Our contacts were mostly gained by personal friendship. We often had friendly chats (even with single workers) over a glass of beer, and at the same time discussed conditions of their respective shops.

These contacts were organized into shop groups, based on concrete issues of the shops or departments. Each group functioned without knowing of the existence of the others. After having established fourteen shop groups out of 36 mills, an open meeting was called, to which about 300 workers responded. These workers were mainly skilled and represented about 20 mills.

An A.F. of L. organizer came to the meeting and tried to hamstring the workers into the A.F. of L. However, this was successfully counteracted due to the preparatory work in the groups.

Officially, the work was carried on by the native comrade who was given personal guidance on how to carry out the policy for a class struggle union. His program was always enthusiastically accepted by the workers and he gained high prestige. He was unanimously elected president of the union.

Underestimation of the Readiness for Struggle on the Part of the Workers

The union grew rapidly. Four hundred members joined within one week, with committees established in 26 shops. In some shops the workers began to talk strike. However, the Section Conference held on Aug. 26th, in its resolutions, did not foresee the possibilities for struggle within the near future, but only the possibility of organization. I also shared this view.

On Oct. 3rd the workers of a department were discriminated against in an important shop. The spokesman of the shop committee in that mill was fired. All the workers of that mill struck in protest. The bosses of the other mills prepared for a lock-out for Monday, Oct. 9th. We counteracted these plans and called a meeting of all shop committees for Oct. 5th. The plans of the lock-out were exposed and we drew up demands to he presented to the employers.

The following morning committees were stationed at every mill to call the workers to a mass meeting. At this meeting the workers accepted the demands drawn up by the shop committees and unanimously voted to strike for these demands and thus counteract the plans for the lock-out. ,

We elected a strike committee of 120, representing every mill and department. However, these workers were totally inexperienced, as they had never participated in any previous struggles. The top leadership consisted of 11 members, who proved to be quite capable; but 6 of them were influenced by the priests and the N.R.A. and were extremely conservative. One of them proved to be a stool-pigeon.

The local N.R.A. stepped in. We were able to expose it because of its composition. Most of the members of the Compliance Board were directly connected with the tannery employers. However, I failed to convince the workers of the character of the National Labor Board, which is in no way different from the local one, and thereby helped to continue the illusions about the N.R.A. This was the worst opportunist mistake in the strike.

Bringing the Party Forward and Combatting the Red Scare

It is true that the time was short to enable us to prepare the workers ideologically against the red scare. Nevertheless, even this was not utilized enough and the Party was not brought forward, with the exception of 2 leaflets issued by the section and the distribution of some Daily Workers in an ineffective way.

As a matter of fact, when Ben Gold came to speak, he did not speak in his own name, hiding the revolutionary significance of his name.

The N.R.A. mediator, assisted by the Labor Board, opened a vicious attack on the outsiders, mobilized the local press, met with the owners, told them that shop committees was a Russian method, plotted with the Mayor and Chief of Police to take the representative of the N.T.W.I.U. for a ride and destroyed the youth group which was organized. The local press viciously started a campaign that the strike would be settled within 24 hours, if the outsiders leave. This campaign penetrated and influenced part of the workers and especially part of the leadership. The top leadership, by a majority of one, decided that we leave town. They threatened a split in the union.

Before we withdrew, we made clear to the workers that the bosses are using this issue merely as an excuse to eliminate leaders and to break the strike.

I was forced to carry on the work underground in a neighboring town through the connection of the party member and the militant group which was organized. Workers fought militantly for rank and file committees and mass picketing. Our organized group was able to expose the lies of the bosses and the N.R.A. and after 2 weeks, putting up a militant fight, a campaign was created in’ the union by the rank and file for my return.

Bringing Forward the Party

After my return to town, in spite of the terror, the workers destroyed the red scare, because the Party was brought forward by explaining the role of the Party in the struggles of the workers. The workers convinced themselves why the N.R.A. and the employers fought against the Communists. It was then that the militancy of the workers intensified in a great tight against the terror. The workers disarmed the Burns detectives, the deputy sheriffs, smashed the windows in the mills, broke the injunction by tremendous mass picketing and went in mass delegations to the Mayor and Chief of Police, warning them that they will be held responsible for my safety, after my life was threatened. Also, we succeeded in establishing a united front with the A.F. of L. glove workers who adopted resolutions for) the strike:

Thus, after 7 weeks of militant struggle, the workers won the following:

1. Recognition of the Union;

2. Recognition of shop committees;

3. Increases in wages of between 20 and 30%;

4. The organization grew from 600 members before the strike to 1,700 members after the strike.

This victory of the workers was made possible because of the following reasons:

1. Because the strike was organized and not spontaneous; we were thus able to eliminate A. F. of L. forces which came in during the early stage of the strike.

2. The organization of mass committees, based on the shops and the free, unbureaucratic approach.

3. The thorough exposure of the N.R.A. and meeting the red scare by discussing openly the role of the Party in the latter part of the strike.

4. Building the Party through individual contacts in the strike which served as a group to carry out the strike policy, although these workers were not taken into the Party at that time, but joined the Party right after the strike.

While there were only 2 Party members before the strike, there are 12 now. From 5 readers of the Daily Worker, there are 60 steady readers in the mills. These numbers are growing. The papers are coming directly to workers employed in the mills.

5. By establishing a real united front with the workers on the basis of concrete issues and grievances in the mills, notwithstanding the fact that most of these workers were members of the American Legion, and some ex-members of the K.K.K., religious, or belonging to other organizations of a fascist character.

The same workers who were ready to lynch a Communist before the strike, were ready now to defend the Communist leaders, even with their rifles, against any attack. As one of these workers said, “If we want to have a strong union, we must have at least five Communists in every mill.”

6. The drawing in of the women into the strike by establishing a women’s auxiliary of the wives and daughters of the strikers.

Communists Can Lead Struggles of the Workers

1. The strike also proved that Communists can lead strikes.

2. That we have underestimated the readiness of the masses to struggle, that, we did not believe that these backward workers will stay on strike for seven weeks. This resulted in going to the N.R.A. and other opportunistic tendencies.

There are big perspectives for the building of the Party, and the life of the union will depend on how strongly we build the Party in that region. The strike has also awakened the political consciousness of the workers and they are now speaking of an independent ticket in the next elections. Our orientation must be to prepare for a real political campaign.

Our immediate steps must be the cementing of the united front with the glove workers A. F. of L. union, the N.T.W.I.U. and the Rabbit Dressers union to build a Labor Council in the county. This must be closely watched and opportunist mistakes must be guarded against. We must draw the most militant elements into the leadership of this body with a strong organized Party fraction that will give leadership to the coming struggles of the workers in this community.

The Party Organizer was the internal bulletin of the Communist Party published by its Central Committee beginning in 1927. First published irregularly, than bi-monthly, and then monthly, the Organizer was primarily meant for the Party’s unit, district, and shop organizers. The Organizer offers a much different view of the CP than the Daily Worker, including a much higher proportion of women writers than almost any other CP publication. Its pages are often full of the mundane problems of Party organizing, complaints about resources, debates over policy and personalities, as well as official numbers and information on Party campaigns, locals, organizations, and periodicals making the Party Organizer an important resource for the study and understanding of the Party in its most important years.

PDF of issue: https://archive.org/download/party-organizer_1934-02_7_2/party-organizer_1934-02_7_2.pdf