‘The Myth of Abraham Lincoln’ by Albert Weisbord from Class Struggle (C.S.L.). Vol. 7 No. 1-2. February, 1937.

I

The name of Abraham Lincoln has long been reverenced in American life. Textbooks in all the schools of the land redound with his glory. Children are taught to look up to Lincoln as the most outstanding man of the people America has ever produced. Even in the ranks of the conscious working class there is a widespread fooling that while the rest of the Presidents of the United States were fakers and grafters, while Washington was a slave-holding aristocrat and avaricious land shark, while Jefferson was a demagogue who knew well how to feather his own nest, nothing of the sort could be said for “Honest Old Abe” who, of the whole crew of politicians that put their hand on the public till, was the one outstanding exception.

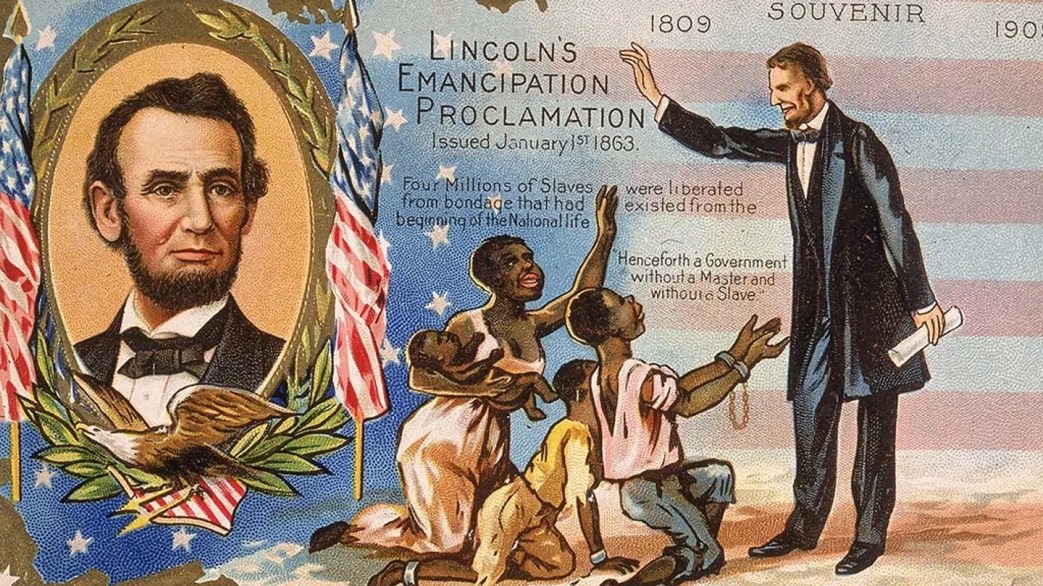

Everyone knows how poor Abraham Lincoln’s parents were, how Lincoln grew up in a log cabin, struggling and persevering till he conquered. In this respect Lincoln typifies the poor but honest boy who made good, whom no amount of money could bribe from the path of honesty and humanity. Lincoln has become the outstanding example of a humanitarian. His phrase is oft repeated “With malice towards none and with charity towards all”. Every school child know how Lincoln refused to allow a sentry to be shot for sleeping at his post. Every Negro is told the story that Lincoln was supposed to have suffered deeply and bitterly over the fact that slaves were sold on the auction block. Lincoln, then, was a man of the people and a friend of the Negro. This is the myth which, with the help of the Communist Party’s pamphlet on Abraham Lincoln, has poisoned the minds of even the most advanced section of the working class.

Such a story is very convenient for the ruling class of today to propagate. Through this myth the American people can be given the idea that a great man, a humanitarian, whose sole ideal is the welfare of the entire people, can be placed in the Presidential chair. The workers can be made to believe that the President can be their friend. The Negro people can be taught that a white man emancipated them and did for they what they never could have done for themselves. This is particularly vicious propaganda so far as the Negroes are concerned, for it cleverly fits in with the ideas of the capitalists that the Negroes are inferior, that of all the peoples of the world, they alone never fought for freedom but had to receive it as a gift from the representative of the white race. When a Negro looks at the history of other peoples he finds that whatever freedom and liberty they enjoyed, they won for themselves through bitter struggles. In America he is told, however, that the Negro was given his freedom on a silver platter through the goodness of heart of the white humanitarian President of the United States who took pity on those semi-brutes, the Negro slaves.

What sort of history is this for the Negro to study? Does this conception increase his self-respect? Does it give him a true picture of the times? Suffice it to say, the fable of Lincoln has done incalculable damage to the Negro people. The sooner it is exposed the better; the sooner will the Negro people break from the Republican Party and other agencies of the bosses; the sooner will a class line be drawn sharp and clear and the struggle of the proletariat for power be put on an unequivocal basis.

The purpose of this article is to break the myth of Lincoln from beginning to end so far as its main political lessons are concerned. Lincoln was not the friend of the Negro, but a friend of the slave-holder; he was not the friend of the working man but a friend of the big railroads whose lawyer he was; he was not the poor boy become President but the wealthy railroad lawyer made President by Big Business. The facts have been hidden but they are becoming increasingly well-known. One need only look at his own speeches and resolutions, to be found in his Complete Works (two volumes) to be convinced of the justice of the present article.

II

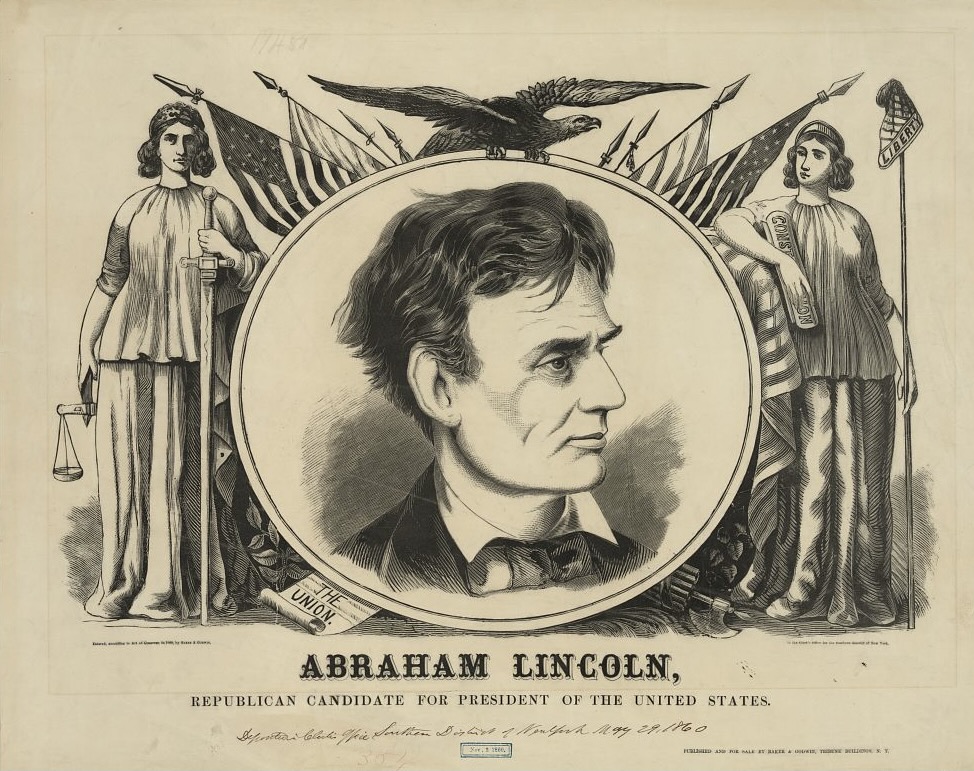

The first point in the Lincoln myth that must be exploded is the idea that Lincoln was a poor backwoodsman who was elected to the Presidency because of his championship of the poor farmer of the West and the laborer of the East. This is the idea that the big trusts of Henry Ford, McCormack, Schwab, Du Pont and others would like the American workers to believe. It is true that Lincoln did start as a poor rail splitter, but he soon saw that his future lay in an entirely different direction, and he became a lawyer. As a lawyer he could not help but be aware of the fact that the rise of the State in the wilderness of the West could only coincide with the rise of capitalism, at the same time the greatest force making for the development of the State and of the law of property. Naturally every lawyer tried to get the up-and-coming railroads as his client; and, on the other hand, the railroads saw to it that all the lawyers of talent or of any influence whatever, were brought over and made into company henchmen.

Abraham Lincoln was no exception to this general trend. “As a green legislator in Illinois he helped to promote the vicious legislation, which went into the laws of the state for excessive and unwise railroad building. As a rising lawyer some of his best clients were the railroads; although at times he appeared against them. He ‘chalked his hat’, or traveled on passes habitually. He was tempted with an offer from the New York Central which, if accepted, would have changed his entire political career. He was a guiding spirit behind the first line to the Far West—the Union Pacific—and he helped determine its gauge, which became the standard gauge of the country. In the famous Rock Island Bridge case he enunciated a right for common carriers which has become an accepted doctrine.” (J.W. Starr, Jr.: Lincoln and the Railroads)

The role of the railroads as a factor bringing about the development of the Western States and aiding anti-slavery capitalism has not been sufficiently analyzed by Marxists as yet. We hope in a succeeding article to deal with the forces leading to the Civil War. At this point all we wish to stress is that very early in his career, Lincoln became a successful railroad lawyer and was soon a man of considerable wealth. For only one of his railroad cases he collected a fee of $5,000, a really extraordinary amount at the time. The New York Central offered him $10,000 a year to retain him as counsel, and it was the high officials of that road who were seated on the platform at Cooper Union when Lincoln made the speech that was to bring him the Presidential nomination.

At this time the West was not hostile to the railroads but was exceedingly eager for railroad development. To get the railroad into their region, each group of Western politicians would make the most fabulous offers and grants of lands to the Eastern capitalists. This was the beginning of a truly golden period for Western railroading. Naturally, the railroads went into the election campaigns of the localities to back up men who were known as railroad men. They did their best to build up their own political machines and the party that responded most to them was the Whig Party. It was to this Party that Lincoln belonged. The Whig Party was the representative of the rising industrialists, financiers and railroad men of the North. These elements were not interested so much in the abolition of slavery as in its restriction to the South. They lived too much on the cheap labor of the cotton picking regions themselves to want to engage in any civil war to free the slaves.

The prevailing opinion in the North among the capitalist elements was well expressed by the Liberal Whigs headed by Henry Clay and typified by Abraham Lincoln. Their policy was to restrict the institution of slavery solely to the South. The Missouri Compromise was their crowning achievement. Lincoln articulated their views when, as legislator in Illinois, in 1837, he brought in the following protest declaring that the signers “ … believe that the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy, but that the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils. They believe that the Congress of the United States has no power under the constitution to interfere with the institution of slavery in the different States. They believe that the Congress of the United States has the power, under the constitution, to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, but that the power ought not be exercised, unless at the request of the people of the District.” Lincoln knew, when he declared that Congress should not exercise its power unless at the request of the people of the District of Columbia, that that District was overrun with slave-holders and their sympathizers and that under such circumstances slavery would never be abolished in the capital.

At this point we can say, then, that Lincoln’s views were:

1. Slavery was on principle unjust, but

2. The abolitionists by their activity were worse than the slave-holders since they tended to increase the evils of slavery by their attacks on the Southerners.

3. Congress had no power to interfere in the Southern States to end slavery.

4. Congress should not interfere in the District of Columbia unless the people requested Congress to act.

It is true that later, in 1849, when he was in Congress, Lincoln did announce his intention to introduce a Bill for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation to the owners, but attached to the Bill was a rider calling for the most stringent enforcement of the Fugitive Slave law. Section five of the Bill declared: That the municipality authorities of Washingtown and Georgetown within their respective jurisdictional limits are hereby empowered and required to provide active and efficient means to arrest and deliver up to their owners all fugitive slaves escaping into said District.” Thus, in the guise of ending slavery in the District, what Lincoln really wanted to do was to pass legislation putting teeth into the laws preventing fugitive slaves from being helped in any way. Lincoln’s proposal to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act was so obnoxious to even bourgeois Liberals of the North that Lincoln never introduced his proposed Bill. But where his sympathies lay could be easily seen by the friends he kept while in Congress. “Apparently Lincoln’s closest associates were Southern Whigs like Stephens and Toombs” with whom he was so closely bound up that he went “so far as to vote, with all Southern members and in opposition to most Northern members, against permitting Palfrey to introduce a bill to repeal all laws ‘establishing or maintaining slavery or the slave trade in the in the District of Columbia.’” (A.J. Beveridge: Abraham Lincoln).

Lincoln’s close friendship with the slave-holders in Congress, in this period, was closely bound up with his fear of the action of the masses and of slave rebellions and with his hatred of the abolitionists. Although Lincoln expressed fear of what he called the “mobocratic spirit,” he did not protest when the abolitionsit, Lovejoy, was lynched. On the contrary, he took the trouble to tell his audience in Worcester, Mass., “I have heard you have abolitionists here. We have a few in Illinois and we shot one the other day.” (See S. B. Leacock Lincoln Frees the Slaves). It is no wonder that Wendell Phillips called Lincoln the “slave hound from Illinois.”

When the Free Soil Party was formed in 1848 with a platform of free labor, free soil and free press, and was obtaining the adherence of such bourgeois democrats as Charles Sumner, then it was that Lincoln’s mentors, the Whig leaders, were even more virulent toward the Free Soilers than they were toward the Democrats, on the ground that the Free Soil Party was giving a foothold to the principles of abolitionism.

III

Lincoln’s views on the question of the Negro were well summed up in his statement made not long before he became candidate for President: “I will say they that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together onterms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race … I will to the very last stand by the law of this state which forbids the marrying of white people with negroes.” This speech was made September 18, 1856. So we see that Lincoln’s anti-Negro views had deepened as time went on.

What Lincoln opposed most of all was the extension of slavery into the North which had become the great danger ever since the Dred Scott decision. But even here it is well to bear in mind the exact reasons for Lincoln’s opposition to the extension of slavery. It was not merely economic but moral. Lincoln was against the extension of slavery into the North on the ground that this would have lead to intermarriage between white and black to which he was deadly opposed. He pointed with horror to the large number of mulattos and said this had been the vilest fruit of the slave regime of the South, that it had debased the whites so far that they had had intercourse with Negroes, even though it was in the form of rape. Lincoln was sure that if slaves were allowed in numbers in the North it would mean more white men would have sexual relations with those people and thus sin against the most holy precepts of God. To insure that Illinois would never tolerate mixed sex relations, Lincoln urged the people to elect Douglas, his pro-slavery opponent, to the Illinois legislature as a watchdog to keep the sex laws of Illinois pure.

Lincoln had his own solution of the Negro problem. He wanted to ship all the Negroes back to Africa as soon as possible. For in Africa these semi-beasts could never pollute the blood of the pure white Americans. He was strong for the development of Liberia which had been started with this purpose in mind. Of course he was in favor only of the very gradual emancipation of the Negroes since he knew he could not ship all of them out of the country at one time. For this reason, too, he was unwilling to judge harshly his Southern brethren for their tardiness in liberating their slaves. At the same time Lincoln strenuously objected to any interference with the institution of slavery in the South on the part of Congress and repeatedly declared that Congress had no power to act but only the people of the respective states themselves.

The feverish capitalist development of the North, the rise of the demands of the West as enunciated in the platform of the Free Soil Party and the relentless drive for more land by the South, toppled the old Missouri Compromise and with it the Whig Party to the earth. Lincoln found himself out of Congress and in a defunct party. The struggle had entered into the higher plane of “squatter sovereignty” where the classes fought it out directly with weapons in their hands. With the Dred Scott decision that gave the South a free hand to enter into all the regions of the North with its slaves, large numbers of moderate elements began to gravitate towards the Free Soil Movement. Out of these elements there was born the Republican Party.

The Republican Party was not a party of war. As a matter of fact, no large organized group in the North wanted war or even suspected it was so near. It was not a party of abolition, but one that merely stood against the extension of slavery. The other demands out forward, such as Free Homestead, Protective Tariff, and a Pacific Railway, clearly demonstrate the petty-bourgeois Liberal character of the organization. To keep the peace these Northern Liberals were willing to bend backward if necessary in their obeisance to slavery. They renounced the term “democracy” and went back to the idea of the Republic (Union). They were willing to take in such people as Lincoln who, however, disagreed with the platform of the Republican Party as too Radical.

At this point it is well to iterate just what Lincoln’s views were. He was against votes for Negroes, against putting them on juries, against political and social equality for the blacks. He was against intermarriage of the races but for shipping Negroes back to Africa. He believed the two races could never get together but that the white would always remain superior to the black. He was not in favor of the abolition of slavery in all the territories of the United States, but was for the Missouri Compromise and for the retention of slavery in the southern parts of the country where he believed Congress had no power to act. He was for the drastic enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act and for the prosecution of all abolitionists who were violating the laws. The Republican Party did not endorse these views. Many Republicans took an entirely different viewpoint and thus it was brought out that Lincoln, the candidate and supporter of the Republican Party, was not in favor of the platform of his own organization.

In his famous debates with Lincoln, Senator Douglas of Illinois pointed out that the platform of the Republican Party included advocacy of the abolition of slavery in the territories of the United States and in the District of Columbia, the rejection of all future slave States from the union and the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Acts. Douglas then taunted Lincoln with the fact that the latter had been against this platform all his life. Lincoln replied: “The plain truth is this … In our opposition to that measure we did not agree with one another in everything. The people of the North end of the State were for stronger measures of opposition than we of central and southern portions of the State.” In short, Lincoln came from Southern and Central Illinois and not from Northern Illinois and he was not for those parts of the Republican program enumerated by Douglas. Lincoln plainly stated that he would vote for the admission of slave States into the union in the future. It was in this spirit, too, that he would fight the Civil War, namely with mercy and charity to the slave-holders.

The chief aim of the Republican Party was the preservation of the Union at all costs. Fundamentally the issue between the Republicans and the extreme wind of the Southerners who wanted to secede from the Union was that the former wanted to keep slavery within the union and the latter wanted to take it out of the union. Lincoln stated the views of the Republicans accurately when he declared that if he could save the Union by abolishing slavery or by keeping slavery or by keeping slavery, his object was the maintenance of the Union. Indeed, had the Southern States succeeded in getting independence, in what a plight Northern capitalism would have been!

Although Lincoln reserved his greatest hatred and contempt for the abolitionists, especially of the direct action variety, John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry forced the issue throughout the country. Willy, nilly, Harper’s Ferry became the campaign issue of 1860. To the South, the “Black Republicans” were tarred with the same stick as “N***r-Lover” Brown.

In vain Lincoln affirmed that Republicans were not Radicals but in declaring the right to control slavery in the territories were only carrying out the precedent of the “Founding Fathers” who had given the control of slavery in the territories of the country to Congress. In vain he appealed to the South that the Republicans did not stir up insurrections among the slaves. “John Brown was no Republican; and you have failed to implicate a single Republican in his Harper’s Ferry enterprise,” he shouted. And again: “Republican doctrines and declarations are accompanied with a continual protest against any interference whatever with you slaves or with you about your slaves. Surely this does not encourage them to revolt.”

Nevertheless, even Lincoln had refused to recognize the Dred Scott decision as final law, and the election of Lincoln did mean the sweeping out of the South from its political control at the head of the government. It meant that the old equilibration of forces was definitely ended, the old balance of power destroyed. Politics had begun to catch up with economics. The slaveocracy was doomed. And when Lincoln was elected with 1.9 million votes out of 4.7 million, the South decided to secede and fight. The die was cast.

IV

We now turn to Lincoln’s method of conducting the Civil War. We can summarize his timid, vacillating, and even deadly policy at times, in one remark: He did his best to prevent the masses from taking matters into their own hands; he did the best on behalf of the slave-holders that a Western-Northern man could possibly do.

When the war first started, a tremendous enthusiasm was shown by the people who knew that the freedom of the slaves would mean an enormous step forward for democracy. Great crowds of recruits flocked to the enlistment stations, only to find that the government had made no preparations to receive them. They were sent home as too numerous to handle and as superfluous. Cold water was thrown on their enthusiasm, while recruiting was officially discouraged. The enlistment stations were not reopened until June, 1862. But it then rather late. A year later conscription was necessary.

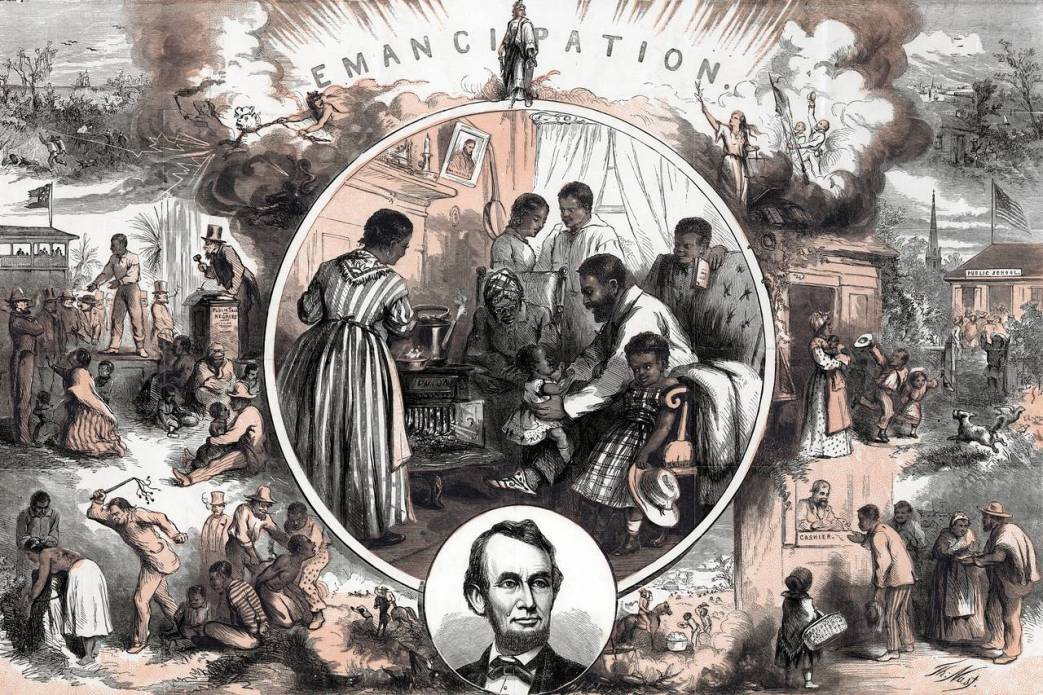

It should have been a most elementary duty on the part of Lincoln and his government not only immediately to free the slaves of all those in actual rebellion, but to instigate a movement of the Blacks for a slave insurrection in the rear of the Southern armies. Instead, everything possible was done to prevent the slaves from rising on their own account. When Cameron, Secretary of the Treasury, in his report in 1861, urged the arming of the Negroes, Lincoln recalled the report by telegraph. “The constant charge of Southern newspapers, Southern politicians and their Northern sympathizers, that the war was an abolitionist war met with constant and indignant denial.” (W.E.B. Dubois: Black Reconstruction) Repeated appeals were made to the slave-holders that if they desisted they could keep their slaves and adequate compensation would be made them. It was forbidden to sing “John Brown’s Body” in the army. In his first Inaugural Address, President Lincoln pledged himself anew to carry out in full the provisions of the Fugitive Slave law. The Commander-in-Chief of the Northern forces in the field, General McClellan, and openly stated that he would take the side of the masters against the slaves, were the issue one of slavery rather than of the union. No doubt Lincoln felt the same way about it.

When masses of Negroes flocked into the camps of the Northern armies, not only were they rejected as soldiers, but the Union generals were informed they had to keep the Negroes intact as slaves for their masters. Lincoln repudiated the notion of General Fremont in freeing the slaves in Missouri although it had become clear that the Union armies were advancing most easily in precisely those areas where the Negro population was the densest. But such a situation could not long endure and when General Hunter faced Lincoln with the accomplished fact of numbers of slaves set free and armed the bars were let down to Negroes entering the army and helping the Union cause.

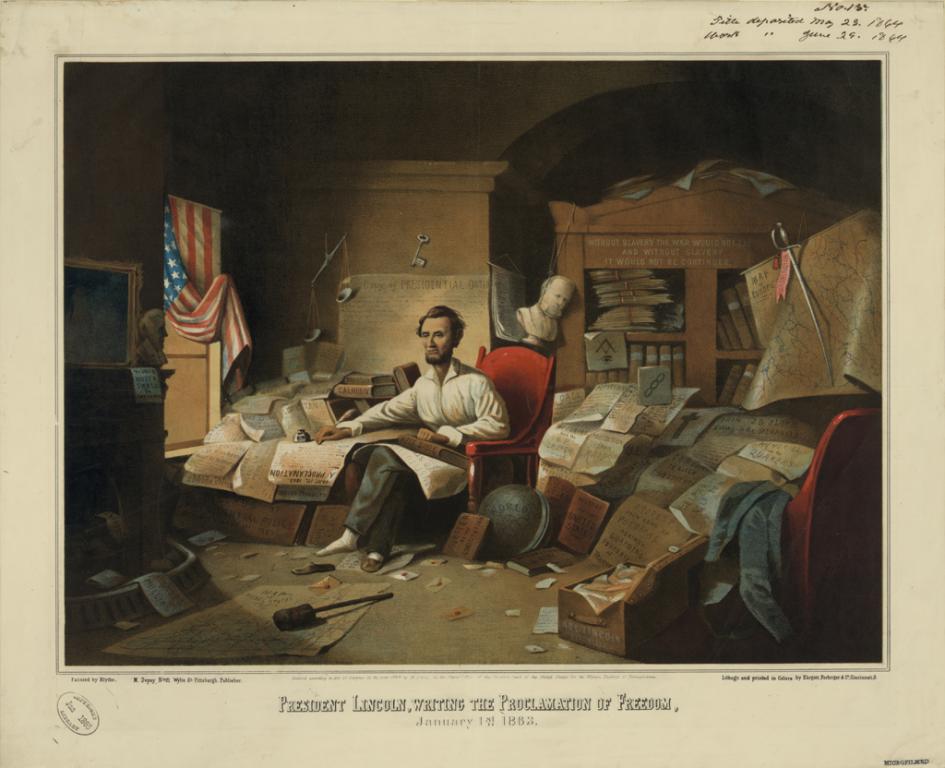

To the very end, however, no slave revolt was ever encouraged, and the South was able to free all her man power for fighting at the front. Only reluctantly, and after waiting till the last moment, when the cause of the North was at its lowest ebb and England was about to recognize the South, did Lincoln issue his Emancipation Proclamation. The net result of all this “humanitarianism” of Lincoln was fearfully to protract the War and to raise its toll to ghastly heights.

As soon as the call came for volunteers, free Negroes everywhere offered their services and everywhere their services were declined. It was only in September, 1862, that a regular Negro regiment was formed. All in all, 180,000 Negroes were accepted. But only under the meanest conditions. Even when giving their lives for the Union—and 68,000 Negroes were lost—they were allowed only half the pay of that the white soldiers got, or $7 a month!

It was no wonder that Wendell Phillips could exclaim: “I do not say that McClellan is a traitor, but I say this, that if he had been a traitor from the crown of his head to the sole of his foot he could not have carried on the war in more exact deference to the politics of that side of the Union. And almost the same thing may be said for Mr. Lincoln—that if he had been a traitor, he could not have worked better to strengthen one side and hazard the success of the other.” (Wendell Phillips’ estimate of Lincoln was: “I will tell you what he is. He is a first rate second-rate man.” (Speeches and Lectures)

If Lincoln was Liberal to the slave-owners, good railroad lawyer that he was, he was not forgetful of the rights of Big Business either. This was the period of the rise of many great American fortunes, but none zoomed so spectacularly as those of the railroads. Corruption and graft were rampant and the Republican Party lived up to its platform handsomely. Not only were charters granted to the Pacific Railroads but cash loans were made running as high as $16,000 to $48,000 per mile of road. Stupendous grants of the very best land, to the total of 129,000,000 acres, were given away. Thus, when the Homestead Act was finally passed and a settler could get a “free” farm, very little good land was left. Big Business had locked the frontier and cornered the market.

Tragically, the Western farmer fought the War to guarantee free competition and individual liberty. For this he gave his life unstintingly during the War. At the end not the farmer of the democratic West, but the oligarchic Trust dominated the scene and took control. The farmer had followed the bell-whether goat, Lincoln, and as usual had been duped by the capitalists of the East.

But if Lincoln had been easy on Northern capitalists, he was not so easy on Labor. The Civil War had the immediate effect of destroying the rising labor movement in the United States. Under Lincoln strikers were considered hostile to the Union and guilty of treason. Strikes were deemed illegal and were broken up by the military. Often Negroes were used as strike-breakers.

As the War continued, the misery of the working class greatly increased. Currency inflation became general, necessities rose sky-high and the standard of living of the masses fell sharply. At the same time Big Business refused to tax itself to pay for the War, issuing 7% bonds instead, which bonds could be bought in depreciated Greenbacks. Meanwhile the tariff was raised from 19% to 47%.

These rough economic measures against the common people coincided with rough political measures. Under Lincoln the writ of habeas corpus was suspended, freedom of press denied, and, to cap the climax, Congress passed the Conscription Act, the first time universal conscription had been decreed in the United States. This Conscription Act had the infamous provision that those who could procure a substitute or pay $300 in cash would be exempted from the draft. Thus could the blood-tax which the War demanded, be shifted onto the shoulders of the poor entirely.

Such unprecedented class legislation had its immediate reaction in the bloody draft riots of 1863 in New York City and elsewhere. The working class of the cities by this time had become thoroughly disillusioned with the conduct of the War. For four days in New York City were conducted violent and bitter struggles of the masses against conscription. In the end Lincoln prevailed, but only after several thousand people had been either killed or wounded in the pitched battles that were fought in the streets.

Here, then, is what we can remember Lincoln for, we men and women of the working class. Under his regime there was a taste of dictatorial action unheard of before in the history of this country, in favor of Big Business and against the mass of toilers. And at the end of the War it was Lincoln’s idea that the planters and wealthy men of the South be allowed to keep their huge estates and property intact. The Negroes were thrown helplessly in the streets. No means were given them to keep alive or to carry on for themselves. Lincoln did not even want to grant them the vote. But it was only the fact that of all the people of the South, only the Negro could be relied on to favor the Union forces that eventually compelled some legislation to be enacted giving the Negroes a meager portion of rights which the whites had enjoyed. But even this was not for long. Under the benevolent banner of the Republican Party and of Big capital in the North, the Southern rulers soon resumed control again. Peace reigned among all the sections of the wealthy throughout the land. The Negroes were deprived of whatever rights that theoretically had been granted them. They were enchained to the soil in peonage, and through the system of share-cropping tillage. The Civil War had been fought for capitalism and not for the masses.

Lincoln was the typical representative of capitalism in this historic crisis in America. He was a mediocrity whom force of circumstances had placed at the helm of the greatest events. He was a petty-fogging lawyer who could not perform the slightest historic act without covering it up with the mean phrases of the property sycophant. He was a white chauvinist who, despite himself, was compelled to endorse the breaking of the chains which the Negroes themselves had carried out without him and against his program. When all the tinsel that has been wrapped around Lincoln is removed, we find him to have been just a homely middle-class representative pushed forward by history and blindly following its currents without understanding them.

Neither the Negro masses nor the working classes have the slightest duty of respect to such a character.

The Communist League of Struggle was formed in March, 1931 by C.P. veterans Albert Weisbord, Vera Buch, Sam Fisher and co-thinkers after briefly being members of the Communist League of America led by James P. Cannon. In addition to leaflets and pamphlets, the C.L.S. had a mostly monthly magazine, Class Struggle, and issued a shipyard workers shop paper,The Red Dreadnaught. Always a small organization, the C.L.S. did not grow in the 1930s and disbanded in 1937.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/the-class-struggle_1937-02_7_1-2/the-class-struggle_1937-02_7_1-2.pdf