Louis Fischer describes his enviable perusal of the shelves at the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow. The Institute began as David Riazanov’s formidable undertaking; to scour the world and collect, contextualize, and publish the extant works of Marx and Engels.

‘A Bolshevik Library’ by Louis Fischer from The Liberator. Vol. 7 No. 1. January, 1924.

ONCE during his British exile Karl Marx was cross-examined by his two daughters. Their questions and his replies he wrote in English on an ordinary piece of copy book paper, and subscribed his signature. The document is now preserved in the Moscow Institute of Marx and En- gels. “Confessions” it is entitled.

“Your most favorite virtue,” the girls demanded. “Simplicity,” answered the founder of scientific Socialism. “Your most favorite virtue in man: Strength.

Your most favorite virtue in woman: Weakness. Your chief characteristic. (Marx spelt it c-h-a-r-a-c- t-e-r-i-s-t-i-c-k). Singleness of purpose.

Your idea of happiness: To fight.

Your idea of misery: Submission.

The vice you excuse most: Gullibility.

The vice you most detest: Servility.

Your aversion: Martin Tupper.

Favorite occupation: Bookworming.

Poet: Shakespeare, Aeschylus, Goethe. Prosewriter: Diderot.

Hero: Spartacus, Koepple. Heroine: Gretchen.

Flower: Daphne.

Color: Red.

Name: Laura, Jenny.

Dish: Fish.

Favorite maxim: Nihil humani a me alienum puto. Motto: “De omnibus dubitandum.” Play as well as work reveal the man.

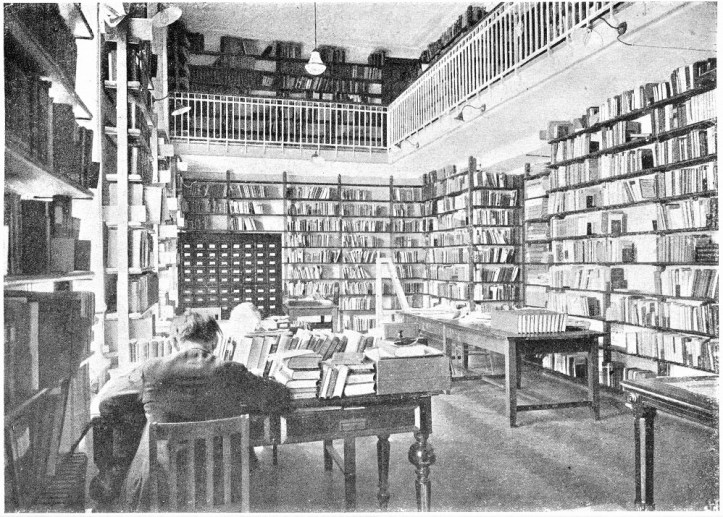

Now Martin Tupper whom Marx mentions as his “aversion” was a German poet. And because Marx hated him all his works can be found on the shelves of the Institute of Marx and Engels. This gives the key to the nature of the Institute. Whatever concerns Marxism and Engelsism, whatever concerns Marx and Engels and helps the student understand the men and their works is to be found in the institute. Already it contains 150,000 volumes and the work of collecting began little more than a year ago.

On special occasions specimen material presenting the institution in miniature is exhibited in the reading room. The development and history of the movement towards fundamental social reform is traced from its modern beginnings to its culmination in Marxian Socialism. Thomas More’s Utopia, James Harrington’s “Commonwealth” (1656), and William Godwin’s “Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness” (1793), are only a few of the many volumes of Utopian literature–in almost every case the precious first edition has been procured–which serves as an introduction to such forerunners of the socialist movement as St. Simon, Fourier and Victor Considerant in France, and Robert Owen in England. The Owenite period of Chartism and Christian Socialism is particularly well represented; many pamphlets by Robert Owen and his co-workers are on view together with numerous propaganda leaflets and proclamations issued by the Chartists, and bound volumes of such of their daily newspaper organs as the “Moral World” (London) and the “Northern Star (Leeds).

Proceeding down the length of the table, the works of Louis Blanc and Proudhon are found in the midst of a veritable treasure house of material leading up to, describing and defining, and outlining the effects of the Great French Revolution. “The Yellow Books” of the revolution are pointed out, and with them originals of documents, notes and memoranda on the conspiracies of Babuef and Buonarroti. One glass case contains at least a hundred pamphlets by, for and against Marat–giving one a tiny inkling of the vast store of first-hand information on the French Revolution piled high in the specialized cabinets devoted to individual countries or subjects.

The second great European revolution, that of 1848, it again richly illustrated. There are the newspapers of the time, the weeklies for and against the movement, revolutionary placards, comic cartoons of the opposing bourgeoisie, government manifestoes and revolutionary counter-manifestoes with, of course, particular emphasis on developments in Germany and France where the upheaval assumed its sharpest forms.

We arrive now at Marx and Engels themselves. The librarian who arranged the exhibition, one is convinced, merely stuck in his thumb at random and picked out a few plums, while the rich, creamy pie remained locked in the fire-proof vaults below. Rodzyanoff, the director of the Institute and the head of the Marx-Engels cabinet is endlessly zealous of the numerous manuscripts, personal letters, photographs, autobiographie which he has collected in many lands and with much effort. The sight of them is reserved for the occasional scholar or compiler and for the student in posterity. The exhibition for the public, however, has some interesting specimens. Marx, be it known, studied Russian in order better to acquaint himself with conditions in Russia. There is on view Marx’ self-made Russian grammar written for self-use in the small, sharp script of the Moses of Socialism. Russians read it and laugh, for Marx deduced the principal parts of verbs, and constructed his conjugations and declensions as his logical brain imagined they ought to be and as they are not. Therefore the mistakes.

We see here several bound volumes of the “Rheinische Zeitung” of which for some years Marx was editor. Original portraits of both Marx and Engels are displayed and likewise some of their early works. Friedrich Engels was of noble birth. An ancient “Who’s Who” is opened to show the family tree and the family coat of arms. The printed records of the Berlin Secret Service are produced and the visitor observes both leaders as they were to the Teutonic Rogue’s Gallery. In 1864 Engels was tried for high treason. The minutes of the trial are here to afford amusement to the curious who would stop to page through the volume. In 1848 Marx and Engels conjointly produced the Decalogue of Socialism-the “Communist Manifesto”; in 1867 Marx himself completed its Bible “Das Kapital.” Both are here in original editions autographed by the authors. In the third year of the present century the ex-Austro-Hungarian government prohibited the printing and sale of the “Communist Manifesto.” A Socialist deputy protested to Parliament and in the process of doing so read the whole manifesto into the Parliamentary Record. That particular number of the record he caused to be widely dis- tributed as was his right, and several copies are preserved in the Institute.

Marx and Engels were the inspiration that led to the short-lived First International to which both the Second and Third of today claim to be the rightful heirs. Be that as it may, part of its property has come into the possession of the Moscow aspirant. The Institute of Marx and Engels owns some of the original English minutes of the First International’s meetings or their photographic facsimiles.

No event is more profusely documented and illustrated than the life of the Paris Commune of 1871. The librarian boasted that the collection here excels the one in the French capital. For the Russian Communist the first modern attempt at practical communism as it was made in Paris is of especial interest and importance, and the Commune Library in Moscow shows by its fullness and riches the time, effort and expense devoted to it.

Isolated features stored in glass cases or framed and suspended on the walls arrest the visitor’s eye: Russian socialist newspapers printed in London in 1895 in Russian; a correspondence between Bakunin the anarchist and Marx the socialist; a letter from Russian Socialists to Marx asking for advice on tactics; letters by Kropotkin the prince-anarchist; “Le Libertaire” the first anarchist periodical ever published, printed in French at 17 White St., New York City and dated June 9, 1858; etc., etc.

The exhibition in the Institute’s reading room is but as a drop of water placed under a magnifying glass in comparison with the sea of material treasured in the individual cabinets. Each of these is supervised by a capable scholar who collects, arranges, and catalogues. Many of the collections which go to form the library of the Institute were purchased in Germany and Austria from bibliophiles and scholars who parted with the results of a life’s labor of love when declining valuta and impossible economic conditions made it imperative. But the greater part of the Institute’s treasures come from Russia proper. The land-nationalization decree transferred to the hands of the state considerable cultural as well as agricultural wealth, for many the landowner-hobbyist and liberal-minded noble whose requisitioned palace contained veritable treasure-troves of print- ed matter on every conceivable subject, not excluding anarchism, single tax, peasant revolutions, etc.

“Capital”–Marx’ magnus opus–consists of three thick volumes. German and scientist that he was, the work is replete with reference to sources. And every book thus mentioned can be had in the Institute. The research worker is thereby enabled to see and examine the threads before they were woven into the cloth; to judge their strength and texture, and to approve or condemn the manner in which the master united them to form the finished product. This is the method throughout. Hundreds of volumes in one cabinet constitute the background for a critical study of Engels’ “Origin of the Family.” The works of the anthropologists, among them Morgan, John Lubbock and Westermarck, rest by the side of an array of writings on the life of the ancient Romans, Greeks, Australian bushmen, American Indians, etc., with the aid of which Engels had sought to prove that the modern family is new as a social unit. On the other hand, shelves are stocked with books endeavoring to undermine such a contention.

His study of capitalism brought Engels to a study of war as well as of the family. He became an authority on military affairs and contributed to the New American Encyclopedia (1859) on that subject. All correlated material–the histories of the armies and navies of all the countries of Europe, the writings of war lords, generals and admirals from Caesar to Napoleon, to Trotsky, records of battles and biographies of soldiers–can be found on the shelves.

“Religion is opium for the people,” declared Marx, and argued that it was dispensed by capitalists with a purpose. Engels agreed. The communists made opposition to religion a plank in their platform. Hence the library of several thousand source books in the original language in which they were issued and in translations. The references which Marx used for his pamphlet “Zur Judenfrage” are here. So also the data for his exhaustive study of the religious situation in the Rhineland with which he was particularly well acquainted.

In this manner all the fundamental theses of socialist doctrine are treated. Thus an entire cabinet numbering at least 5,000 volumes is devoted to the Philosophy of Right, than which, when all is said, there is no question more vital to socialist theory. There are treatises, ancient, mediaeval and modern on the rights of governments (the State and its prerogatives), national rights, personal rights; on law–civil, criminal, martial, international; on the ideology and practice of punishment; on experiences in prison.

A correct knowledge of socialism necessitates a knowledge of Hegel’s philosophy and of that of the anti-Hegelian school. So one naturally becomes involved in a survey of all philosophy, from Aristotle and Plato to William James and Santayana. Not one important philosopher in this long line of descent but that his complete writings can be seen in the Red Room of Count Dolgorukov. It is in the home of this personal friend of the last Romanoff that the Institute of Marx and Engels has been domiciled.

The philosophic basis of Marxism, however, is not complete without Engels’ famous “Anti-Duehring” in which he enunciated the materialistic philosophy which forms the strongest pillar of Socialism. Engels, it will be remembered, took issue with the method of teaching the natural sciences and advanced his own theories regarding true pedagogic principles. The Institute therefore deems it necessary to collect a library covering the exact sciences. We begin with ethics and proceed through aesthetics, chemistry, physics, methodology, algebra, calculus and mathematics in general, architecture, zoology, biology and minerology to electricity and engineering. Nor are the latest works of Einstein too modern. He too is related to Marx and Engels.

The largest individual cabinets are those for France, Germany and England. In the last named America forms a small appendage. In each case there are hundreds of books on the history, culture, economic structure, and social problems of the country. The English cabinet contains the literary productions of the English novelists, poets and playwrights; the works of English economists from Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Malthus to the Webbs, G.D.H. Cole and Keynes; at least fifty thick volumes of British parliamentary records; the biographies of practically every Britisher prominent in the political life of his country during the nineteenth century (Marx wrote a “Life of Lord Palmerston”); bound volumes of numerous daily newspapers and of periodicals during decades upon decades; etc., etc.

But the most interesting department and the one that will eventually be the richest in original research material is the Plekhanov cabinet for books and data on the history of Russian socialism. Comrade Martinov, an ex-Menshevik now hailed and honored as a convert to Bolshevism, is for the present preoccupied with gathering the records of the more distant past, but when he will have arrived at what is present today, the original data, documents, memoirs, etc., that he can find, and that will be placed at his disposal by the government and the Communist Party, will really be unlimited. His cabinet will become a workshop for those who would know the Russian revolution and the history of Communism in Russia. It is a new department–only several months old. In this short period the foundation has been laid for a study of revolts in Russia from those of Stenka Razin, Minyan and Pozharsky to those of 1905, of Kerensky and of the Bolsheviks. The works of all Russian authors have been collected because through them the advance of social dissatisfaction is to be gauged. From the writings of Herzen and Belinsky, to mention only two of the literary critics, one sees the struggle of the Westerners against the Slavophiles, a struggle which agitated Russian intellectual life for many years. Perhaps the issue still remains undecided. The “emigrant” literature of the Bolsheviks when they were still exiles abroad; the “emigrant” literature of today by the monarchist, Social-Revolutionist and Menshevist anti-revolutionists who are in exile at present; Bertrand Russel, Wells, John Reed, Brailsford, Albert Rhys Williams and others of that innumerable caravan who came and saw and wrote books-their volumes are on the shelves forming but the nucleus of what is to be; the apologia literature of Lenin, Trotsky, Bucharin, Radek; much of this is already in the cabinet and surface of the field is but scratched.

The work of the Institute increases in momentum as it proceeds. Next year the number of its books and documents may be doubled.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1924/01/v7n01-w69-jan-1924-liberator-hr.pdf