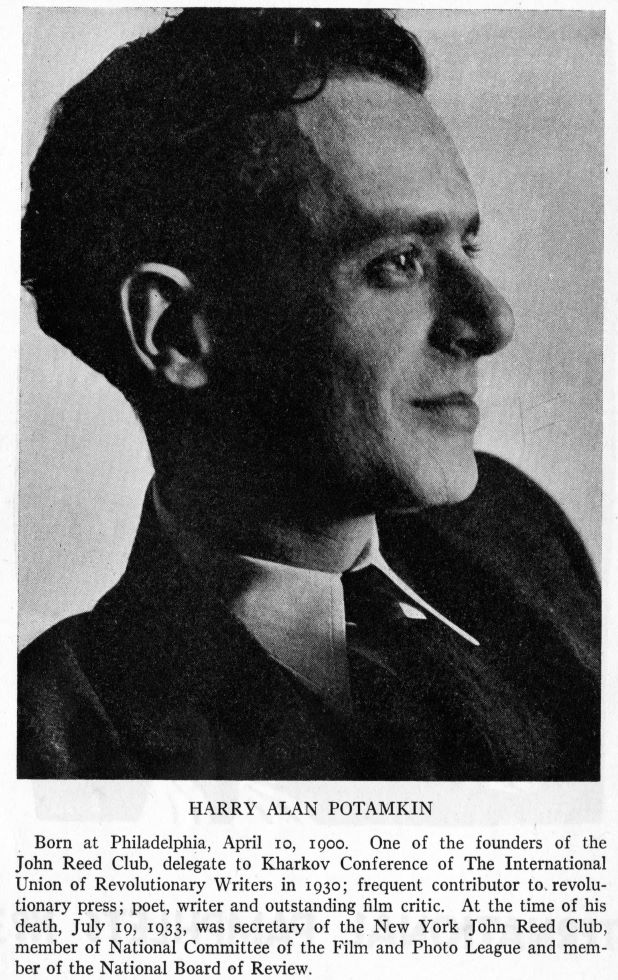

Harry Alan Potamkin (1900-1933) was born in Philadelphia to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. Able to go to college he became social worker in his 20s , directing an experimental children’s play center. He fell in love with film on his honeymoon to Paris in 1926. Soon published, he quickly pushed the boundaries of cinema criticism and began a short, but brilliant career. Always a leftist, his leftism became Communism in 1927 and he became the quintessential artist ‘fellow traveler’ of the movement. Within a year of his Paris trip, he was writing about film. One of the founders of the John Reed Club, he was also a delegate to the Kharkov Conference of The International Union of Revolutionary Writers in 1930. His writings were widely read in the trade, popular, and left press. He helped create and led the Workers’ Film and Photo League at the same time he was a member of the National Board of Review. When he died in 1933 from the effects of starvation, his funeral turned into a political demonstration attended by hundreds of radicals, artists, workers, and intellectuals. his body lay in state at the Workers Center with officials from the John Reeds Club, the Communist Party, and the Young Pioneers speaking. In this piece, he comes to terms with his own past practices, and urges a children’s literature for the Communist movement.

‘Literature for Children’ by Harry Alan Potamkin from The Daily Worker. Vol. 8 No. 46. February 21, 1931.

IT IS good to see that the Communists have come to the point where the child is no longer the object of a blunt approach. Comrade Harper has opened the way in an earlier contribution to the Daily Worker. The projected Young Pioneer magazine would assure a regular, cumulative relation with the child, who must not be lost sight of, even for a moment.

The purists and the timorous will say the child should be left alone. Propaganda is evil for the child. To give the child ideas in contradiction to his daily lessons-in school, home, playground-splits the personality of the child. Well, I have spent eight years with children, five in the very closest of relations, as Director of the Children’s Play Village in Philadelphia. I ran a children’s camp for anarchists-petty-bourgeoisie in “idealistic” clothing. I have written children’s stories since 1927. And my experience sums up now to this: any crumb you feed the child is sustained by propaganda. I insist that not our propaganda, but the negative propaganda of schools, home, playground, betrays the child. What we must find is the revolutionary propaganda that the child can organically take in that will not be simply a routine of automatic imitation. Such propaganda will explain thoroughly and fundamentally the environment to the child, and it will give the child a sense of what it’s all about and what to do about it. It will make him a conscious and complete social being. Childhood is valorous, at least in its own fancy; we must turn that valor to account by making it a fact instead of a fancy.

Let us avoid the pitfall of neutrality in regard to the child. I give myself as a horrible consequence of that laissez-faire conception. My father was an anarcho-atheist in his youth and his sentiments have always been, for the most part, socially sympathetic and anti-synagogue. But a Jew he was in his own mind, and the house did have a polite atmosphere of Jewish sentiments. My father never talked religion, I did not go to the synagogue (though I was taught Hebrew–which I have forgotten and Yiddish–which I remember somewhat), I received no religious training. I grew up with a bad taste in my mouth for God. My father had been neutral, and it seemed I was saved from blunders, as I see blunders now. But no–four years ago I became interested in Jewish lore. Today I can attempt to appraise this lore dialectically, from a Marxist standpoint, and put it where it belongs.

But four years ago I did not view matters dialectically. I thought it enough, when writing for children, to avoid the name of God, and I hoped my stories would be entertaining but neutral, insofar as sectarianism was concerned. Now I find on looking back, that stories convey suggestions as well as definitions, and unexpected things happen in the child’s mind from supposedly neutral stories. The worst part of it is, to me now, that these stories, accepted in a heap by “Young Israel” two, three and four years ago, will be appearing for at least another year; at this time, when I have moved irrevocably to the left and wish to devote myself to revolutionary children’s stories. I ask my comrades to accept my repudiation of those stories, and assist me in the development of an accord with the child of the Young Pioneers. I have made a first attempt in my revolutionary animals’ story, “The March of the Red Bear.” In this Jewish children’s magazine, in an effort to balance my debit, I have published two chapters of this “March of the Red Bear,” a story on the defeat of Denikin in the Ukraine, and am preparing articles on child-life in the Soviet Union, and, in contrast, persecution in the stool- pigeon states of Poland and the Baltic. Bourgeois nationalism does not always operate directly. It can work into the child by suggestion. Similarly all the evils of bourgeois society have subtle, as well as pronounced, ways of affecting the mind of the child, most impressionable of humans. Therefore we must find our subtle, as well as pronounced. ways of defeating this insidious influence, and giving the child a positive working-class code.

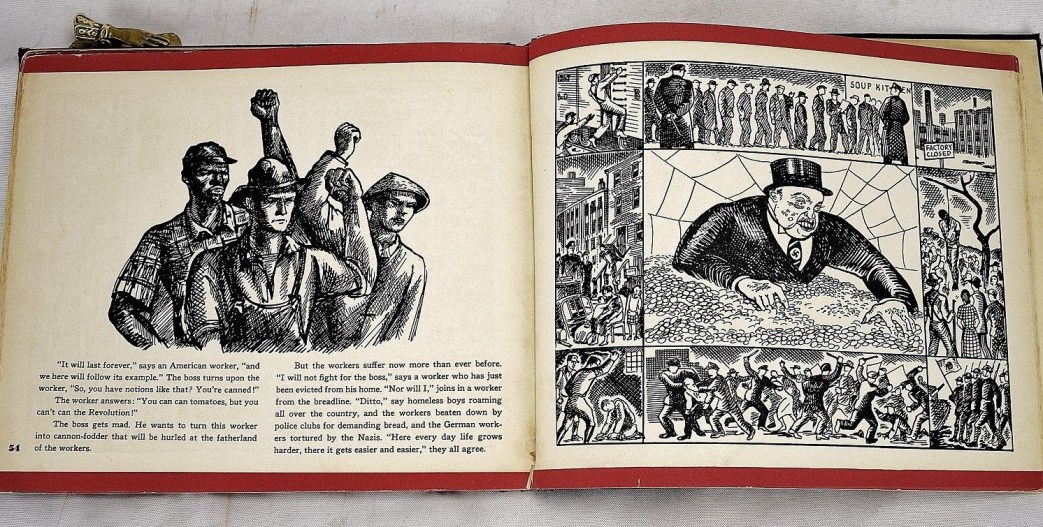

My experience affirms such a project as the Young Pioneer magazine. We must do all we can to bring it about and further it. The stories of capitalist success handed to the American child must be fought with stories of revolutionary success: the lives of Lenin, John Reed, Steve Katovis, Ella May, Gene Debs, Bill Haywood–these will be the child’s folk-heroes. Light humorous verse, satirical and optimistic-limericks and jingles of every sort–and serious poetry to be sung (with music) or to be recited. No closet verse, to be read by a kitchen-stove. Plays to be produced collectively. Stories to be ended by the children themselves–the deductions to be made by them. Puzzles with a revolutionary slogan as the climax, and strip cartoons. We will take the devices that have proved effective with children in the bourgeois school, movie, press, and turn them to our own account with our materials. And we will find our own devices too!

We must remember that while one of our purposes is to sustain the class conscious child, the Young Pioneer, we are aiming for a broad audience. We want to win the proletarian child generally, and we want to win the petty-bourgeois child who is amenable to things we have to say. And we want to say them in such a way that he will be amenable. Remember, we are attacking capitalism and not the child.

The child is social-minded, despite his egoism; and he is stern–that I have seen in the children’s handling of a court in the Play Village. These virtues can be given direction now and for the future.

Moreover, we must encourage the child to participate as critic and as writer, as correspondent, in the magazine.

There should be an editorial board of children. There should be mass-meetings with children. There should be entertainments where the work appearing in the magazine is enacted, sung, recited. And with the publication of the magazine there should be issued also children’s booklets, such as appear by the thousands in the Soviet Union. Unless the work is extensive and coordinated, it is of little value.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1931/v08-n046-NY-feb-21-1931-DW-LOC.pdf