James Connolly writes to comrades in the U.S. of his recent tour through the famine districts of Ireland; its historic roots; and its impact on Irish politics. Transcribed online for the first time.

‘The Famine in Ireland’ by James Connolly from The People. Vol. 8 No. 9. May 29, 1898.

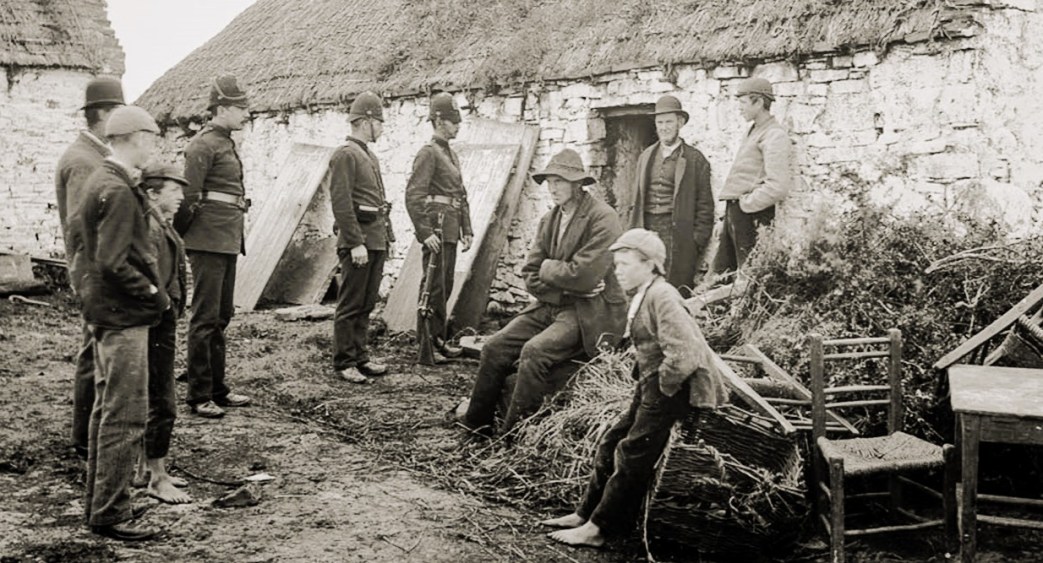

DUBLIN, Ireland. May 22. It is possible that even amid the excitement of the Cuban War and despite the all-absorbing labors of the S.L.P. of America in its prosecution of the far more important class war, there may have reached the United States some information sufficiently explicit to bring home to the minds of our Comrades there the alarming fact that in Ireland at the present moment a large section of the population are suffering from a lack of food, amounting to actual famine.

But as such news is bound to be discounted in its importance by the fact that it only filters through to the people by the medium of a sensational press; and as it is almost certain to be accompanied by suggestions for remedies ridiculously inapplicable to the evil itself, I have ventured to set down here a few of the facts which came under my own observation, in a recent tour through the distressed districts, and also some of the reflections which as Socialist were forced upon me by these facts.

THE FAMINE STRICKEN DISTRICTS.

The particular district through which I extended my investigations is that known as the County of Kerry. My tour comprised within its area the portion of the county extending from the town of Kenmore round the southwest coast to what is known as the town of Cahireineen. This is the famine-stricken district of that county. It is composed almost entirely of mountains and bog land.

From the point of view of the picturesque nothing can be finer than this countryside, sea and mountain combining to charm the eye; but from the point of view of the people who have to extract a living from the cultivation of the soil no place on earth would be more dismal or less encouraging. There is no such thing as a large farm in the neighborhood, from five to Twenty er being as a rule the extent of holdings, and the dwellings of the people, exterior and interior, being of the rudest and most comfortless description. Almost all the population engage during the season in the fishing off the coast in their own boats, but as these vessels are only of the smallest description they cannot venture far from land, and in consequence they I have had, during the past year, the mortification of seeing the larger and better equipped boats of other nations come to their shores and reap the harvest of the sea before it reached them. At the same time the potato crop was attacked with the blight and the greater part of it destroyed, rendered quite unfit for food, and as the potato forms the staple diet of the entire people this second loss was indeed the crowning stroke to their misery. Round a great part of this district it is the custom for the shopkeepers to advance the necessaries of life to their customers during the winter and spring, and to receive repayment for same out of the proceeds of the fishing in the summer, but the practical failure of the fishing last year rendered the latter engagement impossible. The debts remain unpaid, the credit of the customers with the shop-keeper and of the shopkeeper with the wholesale merchant is now exhausted, bankruptcy is imminent, and starvation walks abroad through the land.

INTENSITY OF DISTRESS.

I have personally visited and verified numerous cases in which the whole family have not even had the luxury of potatoes since September, 1897, but have been living for months upon TWO diets, and for weeks upon ONE DIET PER DAY, and that diet composed exclusively of Indian meal and water, without even milk to wash it down. I have conversed with schoolmasters who told of children fainting on the schoolroom floor for want of food. I have seen women, mothers of families, for the sake of half a dollar’s worth of provisions walk seven miles to a relief committee, wait three or four hours and then have to walk the same distance back, have heard from the lips of eyewitnesses (whose credibility I can vouch for) of the produce of shellfish mixed with meal and boiled in water being eagerly devoured by one famishing family, and of the carcass of a diseased cow serving as food to another, have visited districts in which disease (to which this physical weakness brought on by hunger makes these people peculiarly subject) had seized nearly every house, until the place was justly described as “one vast hospital,” in short, I have in one short tour of three weeks’ duration seen an amount of misery so great as to justify the sufferers and all humane men in taking every means in their power to hurl into destruction the power whose administrators and “statesmen” either could not or would not remedy the evil and prevent its occurrence.

BOURGEOIS LEADERS AND GUIDES.

But the leaders of the Irish people at present are themselves as little capable of formulating any real remedy for the evil that even were the forces of England annihilated tomorrow, and our Home Rule politicians installed in power, the economic conditions which have produced the present famine would be left untouched and at full liberty to work similar ruin in the future. Greater promptitude in coming to the relief of the sufferers we undoubtedly would have, more liberal application of public funds to the relief of distress might certainly be expected, but any statesmanlike effort to PREVENT FAMINE BY REMOVING THE CAUSE would only come by the application to agriculture of those “wild” Socialist theories for which our bourgeois patriots have, or profess, such an aversion. For these people I have spoken of are not suffering because of the existence in their midst of an “alien” government, but because of the failure of that system of small farming and small industry on which they depended for their existence, to overcome the natural difficulties presented by their rugged coast and moist climate. Even landlordism, the curse of the Irish race in times past, and the clog and hindrance of all administrative bodies in the present, is only in a minor degree responsible for the present crisis. The root cause lies in the system of small farming and small industry. Isolated on his little plot of ground which in the best of times scarcely affords more than a bare subsistence, the Irish peasant reaps none of the benefits of the progress of civilization, knows nothing of the wonderful results of the organization of industry, his mental horizon is bounded by the weekly “patriot” newspaper crammed with tales and legends of ancient Erin and her chivalry, and destitute of all scientific or economic enlightenment to help the Irish of today, and thus when the full hand of disease is stretched forth over the poor potato crop each peasant strives to avert the catastrophe by his own effort and thus falls an easy victim to the blight which an organized people could easily avert or render innocuous. In the present instance the two disasters which combined to produce the famine, were both directly due to the want of such cooperative effort as it would be the first duty of a Socialist republic to organize, and without such Socialist reorganization the perpetual recurrence of these scenes of misery may be regarded as a certainty, no matter whether our government be Irish or English, alien or native.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE IRISH AND ENGLISH CAPITALIST POLITICIANS in this matter may be briefly stated as follows: The Irish member of Parliament is invariably a political adventurer depending upon notoriety to demonstrate his usefulness to the party paymasters, therefore he must occasionally create a “scene” in the House of Commons, or make a “fiery” speech outside. Thus does he earn his salary and justify his existence to those who subscribe it. The English member of Parliament, on the other hand, is as a rule a wealthy capitalist who occupies his position in virtue of his having made certain donations to the party exchequer, of being donor-in-chief to local charities and chief financial mainstay of the local branch of is party organization.

Therefore he is not expected to show signs of political activity, but only of a plethoric purse. THE IRISH NATIONALIST POLITICIAN IS THE FINANCIAL DEPENDENT OF HIS PARTY, THE ENGLISH POLITICAL PARTIES ARE THE FINANCIAL DEPENDENTS OF THE CAPITALIST POLITICIANS. To use a homely simile, the difference between the English and Irish bourgeois politicians is simply the difference of attitude between the man who has caught a train and the man who is running to catch it. The English party politician comfortably ensconced in the train of fully dominant capitalism, only requires to SIT TIGHT and smile his scorn of the voting cattle whom he calls his fellow-countrymen, but the Irish party politician not yet able to realize an assured income independent of political activity, has not caught the train, and in his rush for it avails himself of every means possible to win the favor of his fellow countrymen that they might be induced to help him into the same position as his English rival.

CLASS DISTINCTIONS AND POLITICS.

The mass of the Irish people being engaged in agriculture, the Irish “patriot” bourgeois seeks to win their favor by demanding legislative enactments in the interest of the farming community, Land Courts to give fair rents (?), compulsory purchase of landed estates in order to establish peasant proprietory, State help in constructing railways, State subsidies for lines of Irish steamships trading for Irish ports, government loans for harbor construction; in fact, he invokes the aid of the State in a manner calculated to put to blush even the most hardened Fabian, and seemingly totally inconsistent with that individualism on which capitalism is based. But when measures in behalf of the working class are mooted, when legislative interference between capital and labor is the subject of debate, then the identity of interests between the English and the Irish bourgeois is made at once apparent by the all but unanimous front both parties present against such “Interference with the liberty of the subject.”

In this respect, it will be observed, they are only repeating the tactics of the bourgeois parties of all countries. Grasping the power of the State, they have ever used it remorselessly in their fight against the pretensions of the landed aristocracy, regarding it then as their savior and a potent instrument of the world’s welfare; but once freed from the danger of aristocratic domination and confronted by a demand that the State power should extent its beneficent operations over the entire community, and raise the wage-slave in his turn to freedom, then the State becomes to the bourgeois anathema, rarely fit to serve as a gigantic policeman for the protection of the private property and furtherance of the private interests of the possessing class.

THE ENGLISH CAPITALIST PARTIES (LIBERALS OR RADICALS) had always looked upon the Irish with contempt in the past, until the year 1885, when a lightning flash of class-consciousness suddenly illumining their understanding they recognized in the Irish Home Rulers the image of their Own younger brothers, seeking to realize the same ends as themselves, by methods foreign to the English bourgeois of today perhaps, but nevertheless wonderfully similar to those his fathers had employed at a similar stage of their economic development. Out of the sudden recognition of this economic affinity arose, over the Irish Home Rule bill, the so-called Union of Hearts (of the Irish and English politicians), a pitiful travesty of that free union of free peoples which Socialism alone can bring to fruition. But this alliance from which Irishmen hoped so much was of necessity short-lived. The Englishman, at first cordial in his friendship to the Irish agitator who only wished to mould Ireland on the political and economic pattern of England, suddenly cooled off when he reflected that if the political freedom of Ireland would indeed hasten the economic development of that country, then English manufacturers would be the first to suffer by the entrance on the industrial battlefield of such a competitor. Better keep Ireland fettered, even at the cost of a standing military garrison, than to allow her freedom and see her develop into another rival in the race for the markets of the world.

The Right Hon. Joseph Chamberlain and most of the wealthier men of the Liberal party had reasoned so all along and therefore remained Liberal Unionists, opposed to Home Rule and Irish measures in general. After the first flush of their love for Ireland had cooled a little, and given time for the selfish passions to reassert their sway, such arguments and reasoning made such wonderful headway among “the leaders of public opinion” throughout England that the Home Rule proposal at the very next election received a crushing defeat from which it is questionable if it will ever recover.

THE HOME RULE BILL.

As Ireland lacks nearly all the requisites for an industrial country, the fear that inspired this revulsion of public opinion was, I believe, entirely baseless, but the result itself is by no means regrettable The Home Rule bill was in fact perhaps the greatest legislative abortion ever foisted upon a people in the name of self-government. The net result of all this play and counter-play of political and social forces during the last twenty years is the utter discomfiture of the middle class politicians, the falsification of all their prophecies, and the wreck of all their organizations. Added to this the various “splits” in the Home Rule camp, by leading the politicians to attack one another, have revealed to the astonished eyes of the multitude the sorry character of the men whom they once idolized.

THE EFFECT OF THIS SITUATION upon the problem caused by the present famine may be briefly told. The English Liberal allies of the Home Rule party represent, as I have pointed out, a fully capitalist nation, or, more accurately speaking, a nation in which capitalism is generally dominant and no longer requires the aid of the State to maintain its internal prestige over reactionary forces. In such a country and to such a party the State is a veritable Frankenstein, and to the dominant class a thing to be restricted and fettered in every way. But the Home Rule party represent an imperfectly developed country, in which LAND and not CAPITAL is dominant, and which, therefore, requires the aid of the State to free itself from the fetters of feudalism. The famine, the direct product of this imperfectly developed state of industry and agriculture, can only be effectually grappled with by the State, and thereupon the Home Ruler advocates State aid, but in so doing receives little if any aid from the English Liberal, who instinctively shrinks from any proposal which might tend to popularize the idea of State interference. Thus the Home Ruler, our Irish bourgeois politician, is landed in a hopeless dilemma. He knows he will be utterly ruined without the English Liberal alliance, nobody will believe in him, nobody will subscribe his salary, he will be dropped like a useless tool. And the English Liberals will not assist him in his demand for State aid, if he pushes it, they will relinquish him. But his constituents, the Irish agricultural population, who believe State aid to be their only hope, will repudiate him if he does not demand it. In such a hopeless quandary the Irish patriot parties, save the mark, flounder along without a definite policy, without a programme, without hope for the future, each separate party seeking to hide its confusion by emitting, like the cuttle fish, a shower of abuse upon its rivals, who retaliate in kind, until the waters of Irish politics stink in the nostrils of decent Irishmen.

Two recent plans prove this: First–Thanks to the clashing of bourgeois interests, the famine pursues its way unchecked.

Second–The class-conscious Irish members grow in strength, in hope and in public confidence.

New York Labor News Publishing belonged to the Socialist Labor Party and produced books, pamphlets and The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel DeLeon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by DeLeon who held the position until his death in 1914. After De Leon’s death the editor of The People became Edmund Seidel, who favored unity with the Socialist Party. He was replaced in 1918 by Olive M. Johnson, who held the post until 1938.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/980529-thepeople-v08n09.pdf