An excellent overview from Mortimer Downing of California agriculture’s specific political economy and how its factory system and multi-racial, migratory labor meant it could only be organized by expansive, industrial unions.

‘California Agriculture Demands Industrial Tactics’ by Mortimer Downing from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 1 No. 7. August, 1921.

INDUSTRIALIZATION of food production exhibits its influence in ranches of the Pacific Slope and especially in California. In present-day culture there are traces of the buccaneer-occupation of land by the Spaniards, and already trustified food culture is in full swing. To understand this region–its needs and absolute necessities–requires that the industrial organizer should appreciate the past competitive conditions and the present urge toward centralization of effort.

In Southern California are still imperial areas under a single ownership and exploited as a unit. Around them are intensively cultivated orchards or gardens–small in acreage, rich in yield. Produce runs the gamut from wheat, potatoes and cotton, necessities, to small vegetables and semitropical fruit, luxuries. There are no farms in California; every plantation is a ranch from the kitchen garden to the chicken yards of Petalunia. Climatic or regional conditions have developed special customs.

California may be described as 800 miles long by 250 miles wide. In this broad expanse the Commission of Immigration and Housing found 1500 labor camps employing from a score or so to thousands of hands. Carlton H. Parker in 1915 estimated the migratory workers in California to be 75,000 persons.

Such then is the human factor which the industrial organizer must mold before he can seize or control the vast membership of “home guard” labor which also functions in this Californian agricultural problem.

Products of Every Clime

Let us first survey the regional industrial geography. Climate varies from the soft, subtropical, frostless belt of the coast to the arid plains, torrid in summer, freezing in winter, but snowless–and then to the mountain areas with their warm “first benches” where ranges abound, and the high areas where summer is brief and winter is long. Apples and oranges grow prolifically in areas not far apart. Cotton in one place vies with the north temperate culture within a day’s journey. Roses bloom in the coast warm gardens, and snow twenty feet deep covers heights not thirty miles away.

These conditions attract to the play ground the idle spendthrift as well as the thrifty, moderately rich grubber. In a word, the luxurious desires of the present ruling class seeks California as a home. All these factors must be reckoned with.

Development of Small Farms

These imaginative exploiters first stole the holdings of the bucolic Spanish grandees. From these vast areas they raped the land of cattle, wheat and fruits. Fertilization was neglected. The soil was looted.

Years ago, spreads of 40,000 or 50,000 acres of wheat were known as “bonanza ranches.” Then intruded the insistent little scizzor-bill. Here and there this class gained a foothold, as see Riverside and Redlands in the 80’s. These little landers forced a “district irrigation” law in 1888 which was fought and denounced by the great exploiters as anarchistic, because it held that water owed a “public duty.”

Irrigation, the basic need of small ranches, and “bonanza” wheat dry farming having clashed, there developed the present agricultural structure of California.

Co-ordinating the industry

Co-operation in exploitation was recognized as necessary. Hence alongside of the orchard is found the packing house. This unit is associated with other packing houses in a marketing concern, so that Californian fruit is not dumped into a middle-man’s market, but from tree to table feels the fostering care of organized ownership.

Oranges, pears, grapes, peaches, apples only blossom and get their skins under individual supervision. Once picked; their way to the market is through the chutes of a socialized machine. Around every packing house a resident labor population grows up. Time put in at the packing plants can be estimated at a given number of weeks; other incidental employment can be figured on and a semi-static population results. These and the 75,000 migratory workers harvest the hundreds of millions of California food products. It has been estimated that potatoes alone have brought more wealth to the Golden State than all her mines.

The Labor Force

Survey the situation: a grape ranch of 100 productive acres has been planted for five years. Roughly speaking, the rancher secures a dozen or less home workers. These are for his stock, run the disc plows, etc., and carry on the routine work. He needs extra labor in the pruning and the picking seasons.

Newspapers advertise the rancher’s labor needs. Ranchers stand et their front gates in harvest time and pick their “hands.” Some engage man-catchers called “employment agents” in the cities. These agents merely put a sign out in the labor market and the migratory worker does all the rest, from auctioning to transporting himself to the job. For the mere address of a rancher the “working stiff” mortgages away his first day’s pay. Then he herds himself to the job and begins to heap up wealth for his smiling boss.

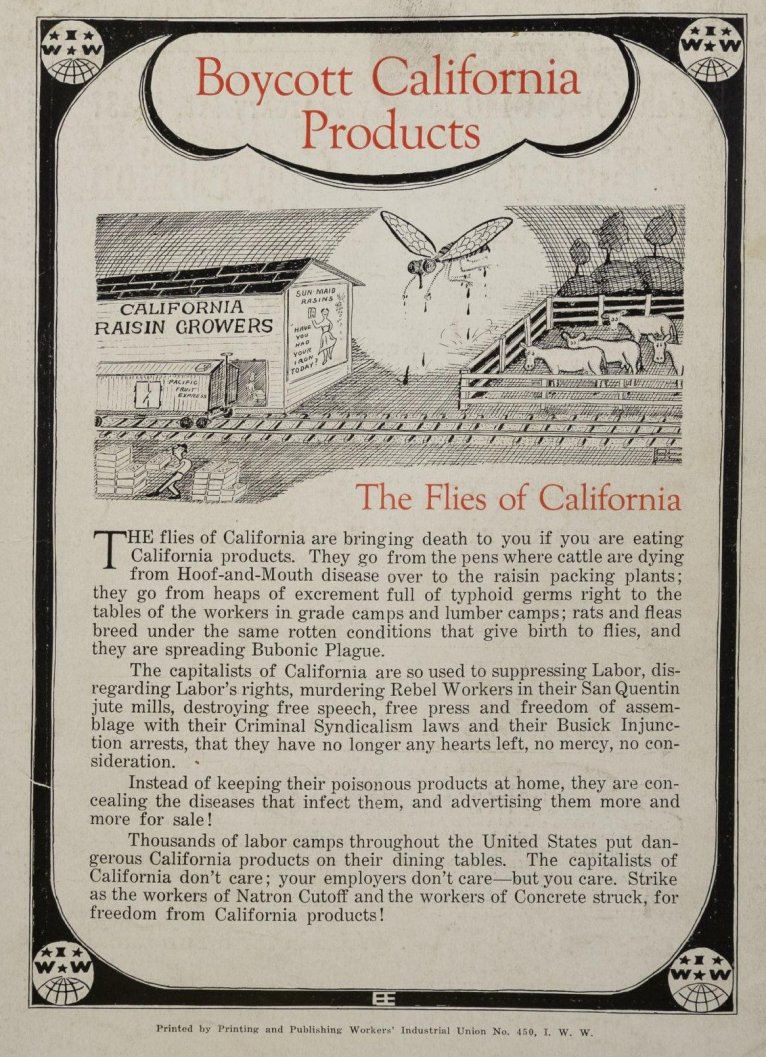

When the grapes are picked they go, largely, either to the winery or to the raisin boxes. The winery is closed, but the dry yards of the raisin industry are spreading wider. Pickers work on a tonnage basis. In the dry yards workers get various day wages, none high. Raisins have been selling at from six to ten cents a pound at the ranches. If workers would figure their value as pickers according to the product they would find that their wages–the most important factor in production because they harvest the wealth and work frantically–rarely compare as one to ten with the relative output of the ranch. Workers should accustom themselves to estimate their pounds of products per day and the current prices as gossiped by every fat-waisted employer they meet. Until the workers think in such terms they will fail to grasp the process in which they participate, or to learn why John Rancher feels poor with but two autos and Jack Stiff is rich with ten dollars and a blanket roll. All the products then of these ranches are smoothly gathered into value heaps under Associated Ownership. There is the Raisin Growers’ Association, the Citrus Culture Association, etc., who not only produce all this wealth of the ranch-side but ally themselves as shippers and merchants in distant markets. It is this associated power of the exploiters which fortifies the California ranchers.

Workers Organize

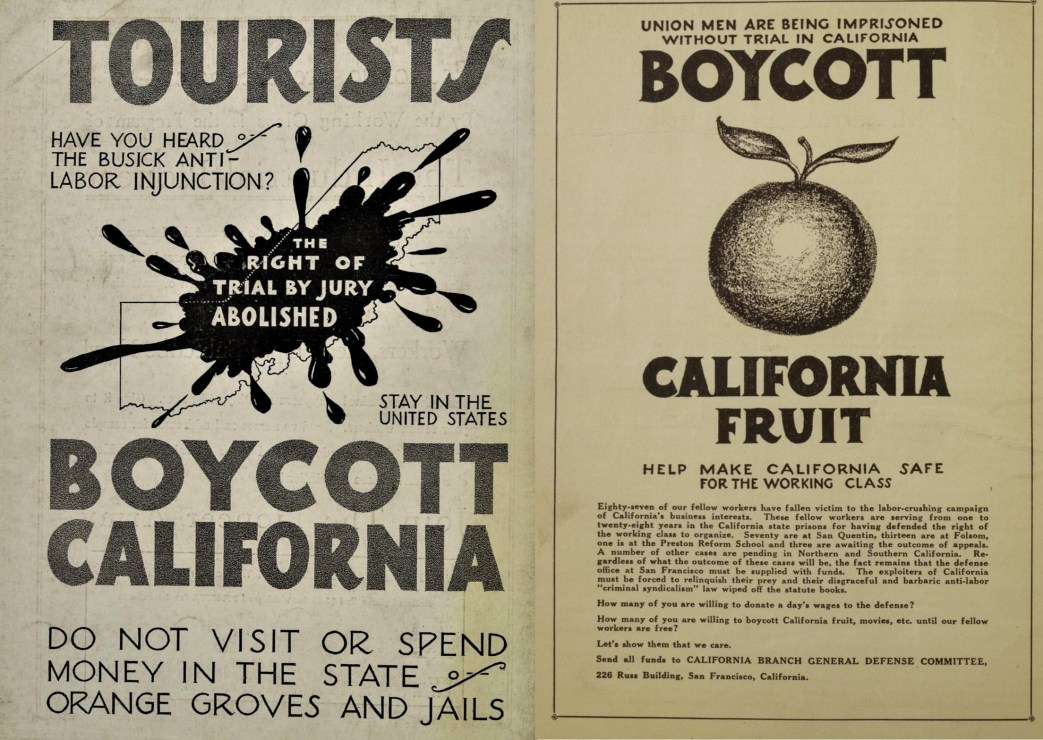

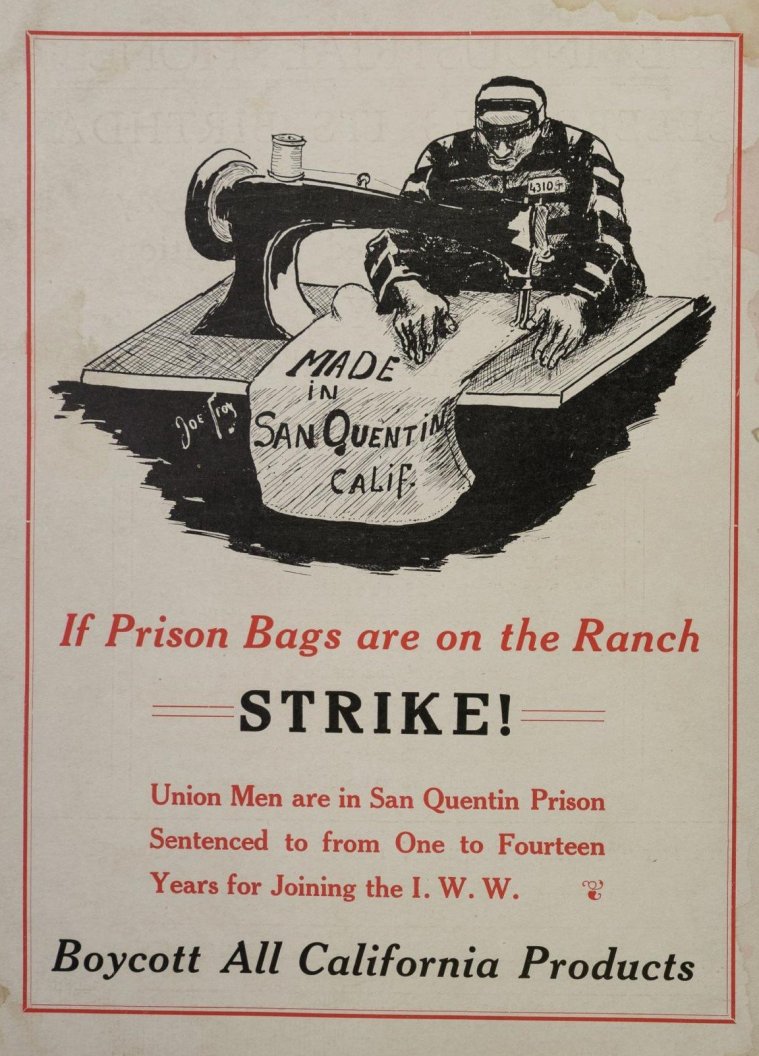

When the workers design an industrial organization, promptly the associated owners pass a law which declares labor unionists to be criminal syndicalists; and fourteen years in the penitentiary reward the spokesmen of toil. Jack Stiff must remember that in the 80’s these same ranchers were denounced as anarchists because they demanded the right to organize and, as small organized producers, own the water of a district and the right to expropriate the princely proprietors who counted acreage in the hundred thousands rather than in the dozens.

In the lessons of the past California directs the wage workers to the Lincoln Highway of Freedom. “Organize!” shouts history. “Organize! Ye are many, they are few.”

When the owners arrange the process of industry so that potatoes go from the field to the desiccating kiln; grapes to the dry yards and trays, and thence to the communal-owned packing house; prunes from the tree to housewife; and all nature’s bounty is ordered for the interest and glory of the few; then let the many grasp the principle of cooperative force.

Unions must be so formed that the home-guard and the hobo recognize a common interest, enlist themselves for a common end, and use their powers for a united gain. These ranchers got their start by organization. Jack Stiff, why may not you?

Factory System Used

Food production on the ranches of California resembles ordinary factory methods. The food goes from the soil direct to the preserving and packing processes close by, with all the efficiency of material going through a mill.

It varies in that all preparation for consumption occurs at the point of origin. In these circumstances the struggle between workers and employers is no longer the bargaining of the neighborhood poor with the local landlord but a battle pitched between organized employers and disorganized bands of wanderers, pitiful as beggars in their need, and with no higher form of organization than sheep. These forces meet at bargaining and the hobos lose. As the manufacturing process forces discipline and organization upon the factory slaves, so the disordered bands of mendicant migratory workers are compelled to organize. Therefore the brief history of the Ford and Suhr case will illustrate the persecution and tempering now thrust upon Jack Stiff and his kind. This battle took place in the hop fields.

Hop Yard Methods

By advertisement and other devices owners of the hop yards sought annually to attract thousands of workers to their fields. Stories of the delightful California climate were circulated in the east, with suggestions that a real picnic with profit and health was in store for anyone who would join the hop-pickers. Throughout the state, also, the unwary were annually lined up—at least 50,000 men, women and children were drafted.

In hop harvesting, the factory character of this agriculture is immediately seen. Hordes of unskilled labor are driven into the vines. The flowers are stripped and placed into bags. All workers are paid by the weight. They are assured that the ordinary worker can earn $6 to $8 a day. Averages about $1.50 are as good as the pickers find. Picking is done on a bonus system, and in 1913 the offer was 90 cents per 100 lbs., with $1.00 if the picker remained three weeks–the average season. In other words, the owners bet nothing against 10 cents that they could make the workers quit. They won 99 per cent of their bets. Why?

According to the investigations of the Housing Commission, temperature in the fields often ran above 120 degrees. Filth and disease ramped through the sleeping quarters. Hygiene was utterly neglected. Men and women, boys and girls, stood in line to use toilets so foul and obscene that stomachs sickened. These were some of the loaded dice the boss rolled when he bet nothing against ten cents, that the toiler would quit before the job was ended.

When the hops were picked and bagged they were sent to the dryer under a number. Then the inspectors threw another pair of loaded dice. Vast quantities of hops were condemned as “dirty,” and at the second verdict the worker was fined, that is, besides the confiscation of the condemned “pick,” an amount of his already-passed product was grabbed though afterwards sold.

All this while the sun sweltered at 120 degrees. Some workers rose at 2 A.M., and were at work an hour later. They toiled and sweated until five or six in the evening. Their pick averaged under 150 pounds. Some few experts exceeded 500 pounds. One of the incidents of this picnic was hop poisoning, by which the picker’s skin was infected by an eruption worse than poison ivy. Heroes indeed were these “picnicers”!

About seven pounds of ripe hops go to make one pound of dried hops. Then the product is baled and ready for shipment to New York or London. It will be noted that at no stage of this agricultural process is it other than a factory process. From the picking to the baling and shipping it is a modern industrial brutality. Concern for human life or comfort is expressed much like that of the cannibals at their feast.

In August, 1913, there were assembled on the Durst Ranches near Wheatland, California, 3000 workers of both sexes and all ages. They comprised twenty-seven nationalities. There were about a dozen toilets for this labor horde, and the whole mass was crowded into a field of scant acreage. In this filthy compound Durst Brothers charged rentals which netted them in excess of $2000.00. The thirst was intolerable, whereupon a cousin of the family exercised the lemonade privilege and charged five cents a glass for citric acid and water. These are only surface incidentals to the evils which launched the battle of August 3rd, when two of Durst’s hirelings and two workers were killed and scores wounded. What really caused the struggle was typhus raging in the camp, deaths daily and starvation among these thousands who were delayed in their entry to the fields by the owners.

I.W.W. Protest

These workers, protesting against overwhelming misery, cried aloud to the I.W.W. Ralph Durst came to the discontented and suggested some form of organization. They picked Dick Ford, a former member of the I.W.W., as their spokesman.

This is what Ralph Durst told Dick Ford at their first interview:

“You will never succeed. I have seen these strikes before. You are beaten by the many languages. Money alone talks around here so as to be understood.” He then struck Ford in the face and ordered him off the ranch.

Next day, Sunday morning, this crowd of twenty-seven nationalities, marching four abreast, orderly took the way from their festering quarters to Durst’s office. There was a great hop wagon in the office yard. Upon this mounted a company of quiet men. They ranged themselves right and left of Dick Ford. In front of each man on that wagon was a solid block of people and each block spoke the language of the man they fronted. There were Japanese, Chinese, Hindus, Turks, Armenians, Syrians, Arabs from Asia Minor, Georgian Cossacks, Kurds from the Caucasus and Transcaspia; all Europe lent groups. Porto Rico sent a man who now sleeps calmly in his bloody grave. Two of his oppressors preceded him to death.

This meeting also was invited by Ralph Durst. It assembled peacefully. When its orderly organization was completed, Dick Ford went to Durst and was again taunted about the ‘unruly mob.’ He presented the demands: More toilets; drinking water in the fields; high-pole men to bring down the higher vines; the right to deal with town merchants for food (Durst had a company store); one dollar per hundred pounds and no bonus.

Sneeringly Durst refused. Ford returned to the meeting, told Durst’s reply and asked the will of the meeting. As Ford talked, twenty-six others translated, each to his group. Then the question was put: “Shall we continue this strike?”

“Yes!” unanimously roared the crowd. Durst was astounded and asked for time. It was granted. Durst then left the meeting and the workers filed back to their quarters. Then Durst, by telephone and messenger, sent for every gun in the neighborhood. He also appealed to the county sheriff, saying he was being expelled from his own land.

After the refusal, the strikers conferred and, at their request, Herman D. Suhr of Stockton, the only I.W.W. member known officially to be present, sent out an appeal by telegraph to the I.W.W. unions for organizers and for money to feed these starving workers. When the telegram was sent, the committee returned to report. At this meeting someone shouted, “Let us slash down the hop vines!” Dick Ford stooped and raised before the crowd a little baby with its face marked by the hop poison. Holding this infant forward, he made this historic appeal:

“Don’t slash down the hop vines. They will sprout again next year. Let us organize so that never again shall men and women suffer as we do. Let us organize so that no more babies will look like this.”

His audience responded with order and good cheer. They were filthy personally, weak individually, but in organization formidable and hopeful with faith in the industrial gospel of the I.W.W.

The Slaughter

While Ford was counseling peace and order, Durst was mustering guns, and thugs to use these guns. He gathered every weapon in Wheatland. On the outskirts of the meeting he disposed his butchers as the consequences will testify to. He had also demanded the sheriff’s posse. Then–

As day died in gorgeous twilight, and these three thousand workers were listening to the peace advices, there came a fleet of automobiles surging through the lane! Guns stuck over the sides of machines. These cars charged upon the meeting, crashed to a stop, the ferocious posse advanced. The meeting opened its ranks quietly. “There was no resistance,” testified the sheriff.

As this armed posse advanced, a Durst thug, Harry Dakin, now boasts that he fired two shots on the crowd. Lee Anderson, near the front of the posse, also fired a pistol. Now in this meeting were scores–maybe hundreds–of children. Their mothers flew to the rescue. In their rush the burly deputies were powerless as straws in a whirlpool. In thirty seconds, so terrible were these mothers in their agony, that no deputy stood erect. Dead, dying and wounded were strewn about the ground. Harry Dakin testified: “I got home, went inside. I heard the lock click. I covered up in bed”…Nobly calm was this meeting, but terrible were the mothers who sought to save their children from these murderous deputies.

And this, in part, was Wheatland, the Bunker Hill of organization by the California ranch workers.

Then began the usual White Terror. Raids, third degrees and free prison beds were the order of the day. False witnesses, press hysteria and class lying were the preamble to the joke repeatedly foisted on the working class in this country. The “fair and impartial trial” ended with the conviction of Ford and Suhr. So terrific were the exposures of life in labor camps that the Commission on Immigration and Housing got busy and compelled some sort of decency in the camps of 1914 and 1915. In 1916 the conditions began to lapse. It was said that the camps were never as bad then as of old. Ford and Suhr from Folsom prison gaze upon a better world. There has never been the utter degradation they fought.

Battle Still Goes on

Since Ford and Suhr there have been other battles in California by the workers. They have passed their Brandywine and Monmouth. They now may be described as in their Valley Forge. Organized ownership has passed its criminal syndicalism statute. Anita Whitney, a philanthropist whose connections are high in station, has been sentenced to fourteen years in prison because she actively protested against such wrongs.

This woman whose only children are the poor and outcast has been convicted of criminal syndicalism and of conspiring to overthrow such benign rule by force and violence. They have convicted J.P. Malley, James McHugo, R.C. Lewis, C.F. Bentley, and are trying others; but just as surely as the horrors of Valley Forge led to the triumph of Yorktown, so will the workers move on to the freedom of Ford and Suhr, Mooney and Billings, and all the individuals whom Californian associated greed holds as hostages.

“We are coming home, John Farmer,

We are coming to stay!”

Industrial Organization and Action

That necessary lesson of organization is sinking into the consciousness of California ranch hands. Workers with red cards in their hearts will organize the workers with red blood in their veins.

There are more discontented workers in California than there is room for them in the penitentiaries. Those owners who have won their ease in the beautiful gardens of California are still so foolish as to deny living wages to non-unionized labor. General Organizer Greed is abroad. Hunger A. Plenty is his assistant. Criminal-Syndicalize that hunger pain, John Rancher!

The lesson which you have demonstrated in your own organization is creeping into the consciousness of the patient masses. Long has labor come onto jobs “loaded like a long-eared Jack.” Labor knows how “forty year’s gatherings” sits on its shoulders. Jack Stiff has learned he can “sleep anywhere on your acres so long as he don’t disturb the hogs.” Labor has seen you Little Landers establish a social control in California. Don’t fool yourself, John Rancher, with Criminal Syndicalism. Labor will organize and own the earth.

You may dam up the River of Progress—at your peril and cost. Food cultivation in California is now industrialized. Ford and Suhr are still on the job to unionize it. Their prison is the light-house. Terror either in 1913 or 1921 avail employers naught. Labor has seen beyond the veil. It signals for organization.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrial-pioneer/Industrial%20Pioneer%20(August%201921)_0.pdf