A circular letter addressed to editors and managers of Party presses internationally from the Comintern’s leadership on the importance of a regular press and suggestions for its attributes..

‘The Character of Our Newspapers’ by the Executive Committee of the Communist International from Bulletin of the E.C.C.I. Vol. 1 No. 1. September 8, 1921.

The third resolution of the Congress of the Communist International dealing with the question of organisation contains a special chapter devoted to the question of our communist newspapers. The Executive Committee of the Communist International desires to supplement this resolution by this circular letter.

Newspapers play a great part in our agitation, particularly in those countries where we have one or more daily newspapers. Our organs, however, up till now have been very unsatisfactory. Have we created a new type of communist newspaper in Europe and America? The reply to this question must undoubtedly be in the negative. Most of our newspapers, in their exterior and in the method of conducting them, are very much like the old social democratic newspapers with the only difference that we endeavour to conduct a different “point of view”. This is not enough. It is necessary that we create a new type of Communist organ, the staff of which shall be composed principally of workers, and which shall grow parallel with the growth of the mass labour movement.

Examine closely our most important daily organs: L’Humanité, L’Interna- tionale, Ordine Nuovo, Politiken, Rabotnicheski Vestnik or even Rote Fahne.

The Executive Committee of the Communist International requests the central committees of all parties to acquaint the editors of our newspapers with the contents of this letter and to raise a discussion upon it.

Do these contain many letters from workers? Are these genuine popular newspapers in the best sense of the word? Does one feel in them the pulse of the present day labour movement?

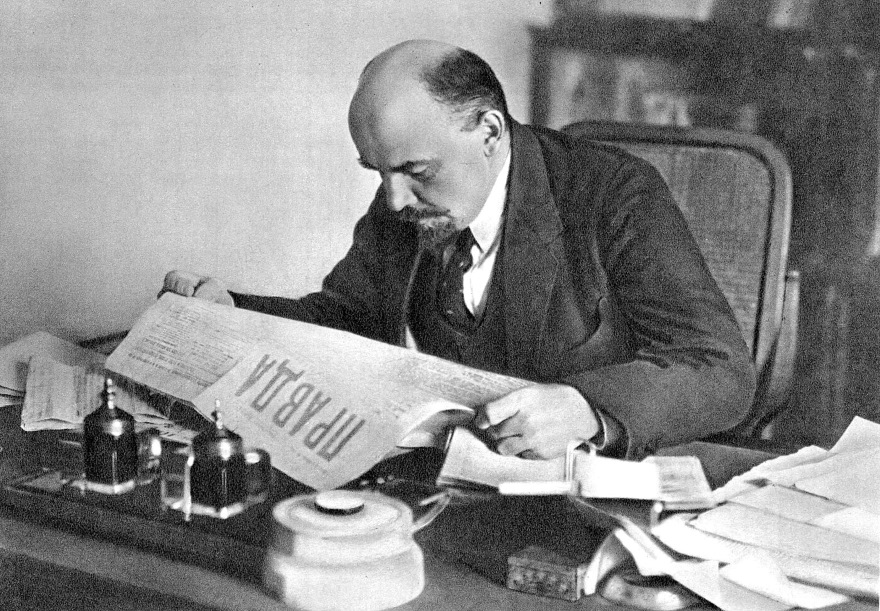

Resolution 3 of the Congress of the Comintern dealing with the question of organisation quotes “Pravda” as it was issued in 1911, 1913 and as it was edited during the period intervening between the February and October revolutions is a classic example of a proletarian newspaper. What was the strong point of “Pravda” at that time? First and foremost, because it devoted more than half of its space to letters from working men and women from the factories. “Pravda” was a special type of Communist newspaper. It performed functions which no other Russian newspaper performed. It differed even in its exterior from all other bourgeois and social democratic newspapers. Half a newspaper was written by working men and women, soldiers, sailors, cooks, cab-drivers and shop assistants.

What was said in these letters, written by skilled and so-called unskilled workers of the lower professions? These letters spoke of the everyday life in the factory or workshop, barracks or the factory districts. In simple language, the details were given of the privation and oppression to which the workers are subjected. These letters exposed the petty tyranny of the minor officials in the factories and works. Taken as a whole these letters drew an impressive picture of the poverty and sufferings which the masses had to undergo. These letters, better than anything else in the world, expressed that growing and seething protest which afterwards burst out into the great revolution. The newspaper became the great teacher of the labouring masses, and the workers themselves have largely contributed toward it. It became the friend of the home in every labourers hut and in every proletarian tenement, at every factory, lathe and at every workers eating house.

It was only necessary for a letter to appear in our paper from a particular factory or barracks for the number in which it appeared to be greedily seized at that factory or barracks. The workers became accustomed to reading this correspondence. The publication of a letter concerning a particular factory would become quite an event for that factory. The exposure made in it would be read by party men and non-party men as well, and the newspaper would become a terror to all the oppressors of the workers and all the “officials.”

We shall be told that in the West the publication of such letters would be difficult and almost impossible. In countries which have an old labour movement, say some comrades, such complaints are carried to the trade unions. In Germany, it is said that the workers are accustomed to report cases of injustice to the trade unions through their officials (Vertrauensmänner).

But the habits and customs of the workers in the West is quite a minor point. Difficulties should be overcome, and we must overcome them at all costs. We repeat, that we must create a new type of proletarian newspaper. A daily Communist newspaper must under no circumstances concern itself solely with so-called “high” politics. On the contrary, three quarters of the paper must be devoted to the “every day” life of the workers. It is precisely because the workers up till now have been accustomed to carry their complaints to the trade unions which in a majority of cases, as is known, are dominated by the reformist agents of capital, we communists must strive to secure that this material flows into our communist newspapers. This will be one of the best methods of cutting the ground from under the feet of the trade union bureaucracy. Our daily newspapers must become real schools of communism. They must serve not only the political but also the economic struggle.

Our newspapers have to compete with bourgeois and other newspapers. We must give plenty of good material, well set up and readable. In one of the columns of the first page there should be a brief description of the contents of the number. We must systematically think out why the rank and file of the working class are attracted by such bourgeois newspapers as the “Morning Post” in England and “Le Journal” in France. We must learn from such papers as the “Daily Herald” which strives to serve all phases of the life of the workers and his family. We must also learn from bourgeois and social democratic newspapers for the purpose of competing with them. Furthermore, we must introduce something that is peculiarly our own and what the bourgeois and social democratic newspapers cannot give. This is precisely the letters from working men and working women from the factories and works, letters from soldiers, etc.

Another objection which we often encounter is that the rank and file of the workers in Western Europe are not accustomed to write, being in a habit to let this be done by their “Functionaries”, their representatives. This objection, too, holds no water. The Western workers are incomparably more literate and educated than the Russian workers used to be a few years ago. If we were able to accustom the Russian workers to correspond with their papers, there can be no difficulty for developing a similar habit among the West European workers. All that is necessary is that the parties assume upon themselves this task and understand that it is of the utmost importance.

At the beginning, of course, things will not run so smoothly. The first articles and letters, will be written awkwardly. Every paper (as it was at first in the “Pravda”) will have to install a special number of comrades who will be engaged in correcting the workers’ letters. We shall have to encourage by all means the workers who begin to write, to help them and write at their dictation or copy their stories. We shall have to rewrite and correct the letters written by the workers, but such work is worth while.

Our papers are now too dry, too abstract, too similar to the papers of the old type. They are made up too much of what is of interest to the professional politician, and contain very little of such items as would be eagerly read by every working woman, every day-labourer, every kitchen maid, every soldier. Our papers contain too many “learned” foreign words, too many long and dry articles. We are too eager to imitate the “respectable” papers. All this must be changed.

In order systematically to carry out our plan we must organise a group of correspondents in every big establishment, in every shop, in every mine, on every railroad line. We must gather those circles of workers. We must patiently and systematically teach them how to write in their papers. We must discuss with them the periodic character of the newspapers and most attentively listen to the practical suggestions which they make.

We must develop a new Communist reporter. He must be less interested in the lobbies of the parliament than in the factories, shops, the workers’ homes, the workers’ dining rooms, the workers’ schools, etc. He should contribute to the paper not lobby gossip, but reports of labour meetings, descriptions of the workers’ needs, the most concrete information about the rise of the cost of living etc.

The “Pravda” has published in its column a large a large number of poems written by workers. These poems from the standpoint of the learned literary critics did not meet the requirements of literary form, but these poems have better expressed the real sentiments of the working class than many of the long articles. The rank and file appreciate very much poignant sarcasm, a vitriolic sneer hurled at the enemy. One caricature which hits the nail on the head is of better use than scores of high flown so-called “marxist” boring articles. Our papers must search for people who are able and want to serve the idea of the proletarian revolution with their pencil. We must make the largest use of what is necessary in a most popular form. We must often have in the paper some stories written by workers, because the working masses like to read and better understand this form of literature. We must often, instead of the customary official daily editorial, insert a more or less remarkable letter by a worker or a group of workers from a certain factory, or a picture of some workers who have been arrested or the biography of a worker who has been sentenced by the bourgeois courts and who has displayed a staunch spirit at his trial.

Less abstractness and more concreteness–this is what is needed for our papers. Every occurrence at the shop and factory should be reflected in our paper. The re-election of the Executive Board of a big trade union should be for us an event of importance and find its expression in the columns of our paper. Every list of candidates put forward by our opponents should be subjected to the severest and most telling criticism. Every detail of the struggle in the shop and factory should be systematically recorded in our paper. Our struggle against our political opponents, beginning with the open bourgeois and ending with the “Independent Socialists”, must be more concrete, more lively and passionate, less stereotyped than heretofore.

In a word, our ambition should not consist in doing everything “just so“, but in endeavouring to give, in addition to good information, which is of course indispensable, good material which will make any of our central party organs readable papers, be loved and under- stood by every worker, and by every proletarian, irrespective of party.

Having thus altered the character of our papers, we shall put them on a different financial basis, and will make them the connecting link between the masses and our party. If we succeed in reorganising our papers in this sense, we shall easily attain what the “Pravda” was able to attain in Russia in the Tsarist days. We shall find the means to collect in small contributions from the workers the sums required for the support of our papers. By changing the character of our papers we shall encourage the workers to compete among themselves in the collection of means for their own papers. Groups of workers and the numbers of readers and supporters of such communist papers will grow with lightning rapidity. These very collections will serve as means for propaganda, all the papers will publish the financial results of the collections. Should a group of our leaders be arrested at some factory, this factory and the neighbouring one will at once begin to collect funds for the maintenance of the families of the arrested. All this will be published in our papers. We will describe in them the workers’ demonstrations, not in the present dry, official style which does not convey anything to the heart or mind of the people, but will give vivid sketches composed by the workers who participated in the demonstrations and will describe them in simple and yet picturesque language. With such editing of our papers every copy will kindle and increase the sacred hatred against capitalism. It goes without saying that in properly conducted communist papers regular and reliable international news must take a prominent place. In accordance with the resolution of the III. Congress, the Executive Committee of the Communist International is organising from September 1st the publication of a communist bulletin which will be published at frequent intervals in 4 languages in Berlin. We shall do our utmost to make the bulletin the means of facilitating the publication of reliable foreign news by our communist papers. Naturally this will only be possible if every party will pay the greatest attention to this essential daily work, and will put the necessary forces at our disposal. A well conducted, well informed communist paper which wins us new friends every day, a paper which serves as a working class platform (in the true sense of the word) und which will be the trumpet call of the proletariat such a paper will be a powerful weapon in the struggle of the Communist parties.

Comrades, let us do our utmost in order to bring into being such a new type of a truly proletarian paper.

With Communist greetings

Executive Committee of the Communist International. President G. Zinoviev.

We beg all the editors of the Communist papers to convene special meetings of collaborators and to call to those meetings the workers from the most important works and factories. We ask you to discuss at those meetings the plans proposed in this letter, and to communicate the result of these discussions to the Executive Committee.

We also beg of you to discuss these plans at bigger town and regional party conferences.

We are willing to open in the columns of the “Communist International” a much needed discussion on this question, in order to arrive at the most practical and most desirable alterations by means of this international interchange of opinions.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/publications/n1-n5-jul-07-1921-sep-08-1922-Bull-Exec-CommCI-Feltrinelli-reprint-1967.pdf