A turning point in 1920s Europe was the June 9, 1923 overthrow of Agrarian Party leader Aleksandar Stamboliyski by the Bulgarian military, instituting a reign of terror under the White Guard rule of Aleksandar Tsankov. At the time the Bulgarian C.P. was one of the most influential in the world, a genuine mass party it was the largest single Party in Bulgaria and failed to intervene in the coup. Repression was met with lost armed risings, followed by guerilla operations, and then terrorism with the Bulgarian C.P., as it was, destroyed in prison, exile, and the grave over the next years. A generation of revolutionaries wiped out. At the height of his authority in the summer of 1923, Radek delivered this lengthy report on the background as well as his criticisms of Bulgarian Party at the E.E.C.I. of June 23rd, 1923 shortly after the coup.

‘The Coup d’Etat in Bulgaria and the Communist Party’ by Karl Radek from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 6-7. September-October, 1923.

We are placing before you a manifesto to the Bulgarian workers and peasants. In this manifesto we make clear our attitude to the Coup d’Etat in Bulgaria and we outline in a general form the policy of the Bulgarian Party. We are of the opinion that the Bulgarian Coup d’Etat is a decisive defeat of our party. Let us hope that it will not be a crushing defeat. Nevertheless, it is the most serious defeat ever experienced by any Communist Party. It does not even bear comparison with the victory of Fascism in Italy, for the simple reason that the Italian Communist Party is young and weak, while the Bulgarian Communist Party has behind it over a quarter of the electors and is the largest and strongest mass party in Bulgaria. Thus this defeat is not only a testimony of the growing strength of counter-revolution, but it is also a positive defeat of the tactics of the Communist Party.

The Meaning of the Bulgarian Defeat.

The reasons which induced us to define our attitudes to the situation in Bulgaria are as follows:

1. In the first place the Coup d’Etat in Bulgaria is part of the victorious advance of world reaction. The peasant Government in Bulgaria was the only body incompatible with the bourgeois domination in the Balkans, the only Government which, notwithstanding its efforts to carry out the conditions of the Neuilly Peace Treaty, was looked upon by the bourgeois world in the light of a Government of peasants opposed to the urban bourgeoisie. The way in which the organs of Fascism, from the “Morning Post” to the Stinnes Press, welcome the fall of Stambulinski, is sufficient proof that the Balkan overthrow is to the advantage of world reaction.

2. The new Government resulting from the Coup d’Etat and alleged to be a democratic bourgeois Government, is in close contact with the Russian counter-revolution. There is no doubt whatever that Wrangel officers are playing their part in it. The interest shown by the counter-revolutionary Russian Press, headed by the Rul” in the Bulgarian Coup d’Etat is a sign that it expects from it a strengthening of its position.

3. Looked at from the world-political viewpoint, the Coup d’Etat is an incident in the general struggle of the two powers aspiring to the hegemony in Europe-France and Great Britain. The fall of Stambulinski and the victory of the new White Government mean that the British Government has gained a point in its encircling policy in the East against Soviet Russia. The little Entente, the tool of France, supported Stambulinski because the policy of his Government was one of fulfilling the Neuilly Peace Treaty. Even if Great Britain and Italy did not give directly material support to the Bulgarian Coup d’Etat (Italy is concerned about the Adriatic and therefore engaged in a struggle with Jugo-Slavia), there is no doubt whatever that Great Britain and Italy are favouring the victorious clique which brought about the Coup d’Etat. When the Jugo-Slavian Government wanted to take diplomatic measures against the Bulgarian Coup d’Etat, Young, the British Ambassador in Belgrade, put in his veto. We are certainly not the keepers of the Neuilly Peace Treaty, but in estimating the present world-political situation, the fact is that it is Britain which is taking up the initiative in the encirclement of Soviet Russia. Viewed in that light, this means another point gained in the encirclement of Soviet Russia. This alone is sufficient proof that we are faced with an event of great political significance to which we must pay the greatest attention.

4. It is evident that this victory of the Whites in Bulgaria will be an encouragement to the Fascisti in all countries. In three hours a handful of officers brought about the overthrow of a Government which has behind it a large majority of the peasantry. This is, of course, encouraging to the Fascist adventurers in all countries, especially in Czecho-Slovakia, Germany and Austria.

5. For the first time a big Communist Party was in the fray. It lost the battle and what is even sadder–the Bulgarian Press of June 9-16 is to hand-it does not even realise it. Throughout the first week following the defeat, the party did not understand the causes for it, and defended its attitude as correct Communist tactics. We must confess that not a single Communist paper in Europe of its own accord said that this meant a defeat of the Communist International. A defeat which is to be ascribed not to the superior strength of the enemy, but to lack of fighting will in the Communist Party. There are even Communist papers which reprint and circulate the theory of the Bulgarian comrades. Therefore it is necessary, not because we wish to play the judges over the defeat of one of our parties, but for practical reasons that before enlightening the wide masses as to its errors, we communicate them to the leaders: of all Communist Parties represented here. I repeat that this is necessary because we run the risk of the same errors being committed in Czecho-Slovakia where the situation is very similar. They might also be committed in Germany.

With your permission I will present a short survey of the events and will bring back to your memory the most important facts required for the just appreciation of the position.

The Social Structure of Bulgaria and the Political Groups.

In the first instance we must consider whether the Bulgarian comrades could have avoided this defeat. Is the social and political structure of Bulgaria such that it might have been possible to prevent the Coup d’Etat of the Whites either alone or in alliance with the peasantry? Our answer is in the affirmative. The social structure of the country is such that 80 to 90 per cent. of the population are peasants. Out of 700,000 independent farms, 285,000 belong to peasants with less than 30 dekas of land. Considering the state of agriculture in Bulgaria, those are semi-proletarian peasants. 263,000 peasants farms have between 30 and 100 deka. Our Bulgarian comrades say in their report that every peasant in Bulgaria possessing less than 100 deka is a poor small peasant. This means that over 500,000 of these peasants were fit to be our social allies. The bourgeoisie in the cities is very weak, in fact a big bourgeoisie is non-existent. The town bourgeoisie consists of tradesmen, artisans, speculators, intellectuals, and bureaucrats. Thus, there is no class which can be considered strong because of the role it plays in production. The working class, though small, is better organised than in any other country. Considering that out of 100,000 workers, 40,000 are members of the party, we must admit that such a percentage does not exist in any other country. The last element is-militarism. Owing to the Neuilly Peace Treaty, the army is demobilised. This is a rough sketch of the social balance of power.

The Political Situation.

The bourgeoisie and the generals who ruled for 40 years became bankrupt by the war, and were swept away by the indignant peasantry. The result of the poll at the elections is a testimony to this. In 1920 the combined bourgeois parties obtained 250,000 votes, in 1923-219,000 votes, while the Communist Party obtained in 1920–148,000 votes and in 1923–230,000 votes. Thus the Communist Party obtained more votes than all the bourgeois parties taken together. The strongest party, which as a Government Party was able to influence elections, is the Peasant Party. The Government Party had 121,000 members on its list, out of whom 115,000 were poor, or at least small peasants. Thus it was a party with which (in view of its social composition) we could enter into a coalition. You are aware that this party, because of the small clique of intellectuals which leads the peasantry, is more in sympathy with the small section of the rural bourgeoisie than with the wide masses which are behind. Because it realised that the Communist Party was the only strong party capable of competing with it as far as the peasantry are concerned, it was persecuted by the Government, which created much bitterness within the party. However, there is no doubt whatever that the Communist Party omitted to do what it should have done either to force the Stambulinski Party into the coalition or to split it.

The party has neglected propaganda among the peasantry. This is borne out by events. It has shown itself unable to expose Stambulinski to the peasantry, thus bringing disunion into the Peasant Party, in the event of Stambulinski refusing the coalition with it.

Moreover, I have not mentioned a very important political element in the entire political situation which showed that we were also able to operate against Stambulinski.

In the recent history of Bulgaria the Macedonian question played an important role. Macedonia, which is inhabited by peasants of whom it is difficult to say whether they are Serbs or Bulgarians, has for a long time been a bone of contention between Serbia and Bulgaria. Owing to the defeat in the war, the Peasant Party and Stambulinski renounced their claim on Macedonia. This was done not only formally, for Stambulinski, in order to strengthen his position, arrived at an agreement with Jugo-Slavia at Nisch, as a result of which he initiated a sanguinary persecution of these old Macedonian organisations. Socially, these organisations are composed of small and poor peasants. They have a revolutionary past, have fought against the domination of the Turkish big landowners, have struggled against the bourgeoisie in Serbia, and preserve old, illegal, revoltionary organisations. They have for a long time sympathised with the Russian revolution. The Macedonian organisations were a social factor with which we could ally ourselves. We could ally ourselves with them against Stambulinski. They are an important military factor with big illegal, armed organisations at their disposal. Allied with them, we would have been able to bring pressure to bear on the Stambulinski Government, inducing it, even if it must carry out the conditions of the Neuilly Peace Treaty, to abstain from persecuting these organisations. Not only has the Party not done this, but what is more characteristic, the Macedonian question does not seem. to play any part at all in their conception of the actual situation. Two months ago Kabaktchiev published an article on the situation in Bulgaria, which appeared in the ” Inprecorr,” and which I have just re-read. Throughout the article, in all his tactical computations, there is not a word about the Macedonian question.

The National Situation in the Balkans.

In defending its policy the Party used the following argument: We are in a position to assume power, but the international situation is such that we shall be crushed. I draw the attention to this argument of these comrades (I mean especially the Czech comrades) who, in their own country, have frequently made use of similar arguments. The Bulgarian Party’s view is that it can be victorious only when victory drops down from the blue, when it is easy, when it is surrounded by a sea of revolution.

The isolation of Bulgaria, which is surrounded by Serbia, Greece and Roumania, is certainly a menacing factor for the Bulgarian Revolution and was bound to have its effect on the party. This situation was, however, made easier by the Greco-Turkish war and the Greek Revolution, which gave an impetus to the revolutionary movement in the Balkans. The Bulgarian Party remained passive during the Greek Revolution, it awaited a more favourable opportunity. The counter-revolution was quick to understand that in politics it is essential to take the initiative into one’s own hands.

Viewed from the international standpoint, the position of the counter-revolution, a clique of old officers and bureaucrats responsible for the Coup d’Etat, is also far from being easy. This Government, whose main support is Macedonia, is a danger for Serbia, whom it therefore fears. Nevertheless, the counter-revolution dared to act. The counter-revolution recognised what an old Communist Party failed to recognise, viz., that in a decisive moment victory is to those who dare, that there is a logic in facts accomplished and that by taking the initiative into one’s own hands one makes the situation more difficult for one’s opponents.

The Cause of Defeat.

Comrades, our Bulgarian Party was defeated because it was a Social-Democratic Marxian Party, which did great things in the field of propaganda and organisation, but which showed itself unable to accomplish the transition from agitation and opposition to deeds and action in a historic moment. We are faced with the same danger in many of our other parties. The attitude of our Bulgarian comrades to the peasantry and to the national question was due to the fact that the Bulgarian Party lacked the audacity required for revolutionary struggle. Only because it dared not fight, the Bulgarian C.P., in spite of our Bulgarian comrades’ correct interpretation of the Macedonian problem, was unable to set the necessary machinery into motion.

The defeat is a decisive one. It is ridiculous to assume that in a peasant country, where the masses are scattered, those who dispose of the State apparatus are unable to maintain their position for a considerable time, in spite of their social weakness. The moment when the Coup d’Etat took place in Sofia was the moment for action, for we were the only power centralised throughout the country. The railway men and the telegraph servants were on our side, we had communications in our hands, as well as the working masses on our side. Moreover, there is no doubt whatever that at the moment when the Peasant Party was fighting for its existence, we were given a historic opportunity to enter into coalition with it, regardless of everything which separated us from it. When Kornilov dared to rise against the Provisional Government we were not in a better position to Kerensky, nay, even in a worse, than the Bulgarian comrades to Stambulinsky. At that time our party brought all its energy into play in the defence against Kornilov. Moreover, after the Kornilov affair, Lenin, in his article on compromises, made a direct offer to the Mensheviks and Social-Revolutionaries.

The Bulgarian Party does not try to understand its defeat; it is, on the contrary, endeavouring to excuse it. We have before us the manifestos of the Bulgarian Party. They are the saddest part of the defeat. We have here the manifesto of the 9th and that of the 15th, and a number of articles. The attitude taken up by the party in these documents is as follows: Two cliques of the bourgeoisie are fighting; we, the working class, stand outside, and we hope and demand that freedom of the Press and all other good things shall be given to us. Such are the contents of the manifesto of the 9th.

When a section of the working class, without any guidance by the party, sided with the peasants in their struggle, it was disavowed by the party. In its manifesto of the 16th (which is the most discouraging document I have ever read) the party makes the following amazing statement:

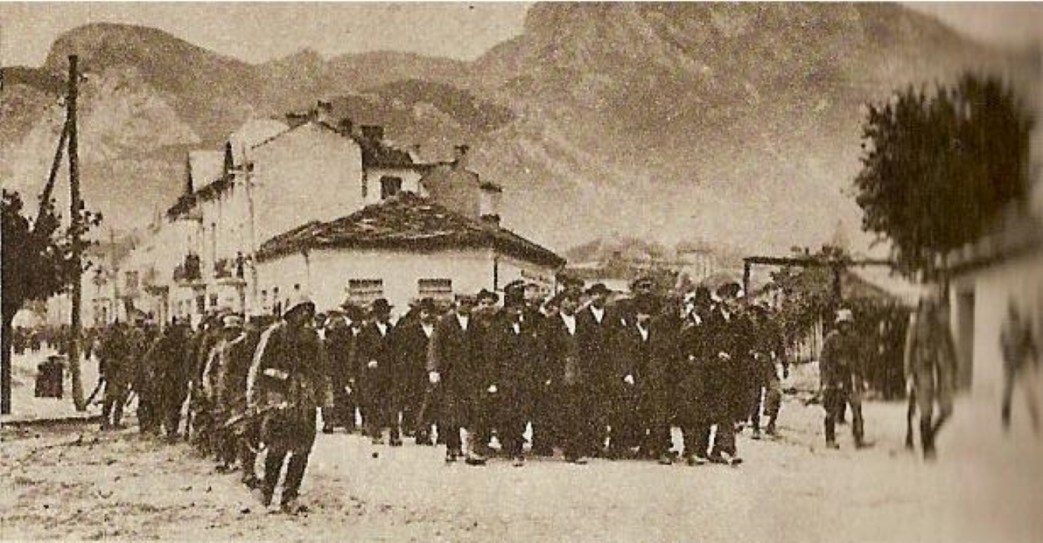

“Hundreds and thousands of workers and peasants are being arrested and brought to trial on the strength of the emergency law against banditism and under the pretext that they resisted the Coup d’Etat. We declare that in the confused situation which arose between the two bourgeois cliques when civil war broke out, a section of workers had to defend their lives and their families, and did not participate in the struggle for power.”

The workers were neutral, and only when in peril of being shot did they take part in the shooting, because they have wives and children. But they did not fight against the Coup d’Etat.

The theory of neutrality between the two bourgeois camps, the declaration that we are the only party defending the constitution (the constitution on the strength of which King Boris conspired against Stambulinski, and for which our comrades are in prison) indicate not only to serious defeat, but also the internal dissolution of the party leadership. We should be only too glad if the party proved itself to be in a healthier state than its leaders. We want at any rate to be quite open with the comrades about these facts.

We consider it the duty of the Communist Party, in the event of struggle between the capitalist sections of society, which true to their traditions represent the interests of capitalism, and the petty-bourgeois peasant sections, not to play the role of a spectator and a neutral element, but to endeavour (if it is not strong enough to assume power) to enter into coalition with the petty-bourgeois sections of society. It is not Marxian, but just pedantry to assert that we are confronted here by two sections of the bourgeoisie which are equally hostile to us, when in fact the peasantry has not yet ruled in any country. To produce at this juncture the Third Volume of Capital and to assert that the peasantry is also a section of the bourgeoisie, amounts to the abandonment of one’s revolutionary duties.

The Executive Committee and the Bulgarian Party.

I will now endeavour to explain how far the Executive is to blame for this affair. I will give you a few facts, which will enable you to judge for yourselves. Already as far back as the Second Congress, small groups came from Bulgaria who blamed the party for not assuming power and for being inactive when the régime of King Ferdinand collapsed. Some members of these groups represented a type of adventurers, such as Khartakov, who reprinted articles about terrorism by Kautsky and at the same time played the part of a “left Communist.” But these groups had also good proletarian elements which were rather confused in their ideas. We examined their accusations very carefully, for we knew by experience in Germany (the Kapp-Putsch) how necessary it is to pay heed to such warnings.

The Commission entrusted with the examination of these accusations found that those of a concrete nature were not justified. It was clear that the party could not assume power in 1918. Nevertheless, I must confess that we were somewhat uneasy, and the result of our suspicion that there was something rotten in the State of Denmark was the manifesto to the Bulgarian Party Conference of May 4th, 1921.

I will read you this manifesto which is not very long:

“THE MANIFESTO of the Executive of the Communist International to the Congress of the Bulgarian Communist Party.

“The Executive of the Communist International sends fraternal greetings to the Congress of the Bulgarian Communist Party. The Bulgarian Communist Party, the heir to the brave and consistent party of the Tjesmaki, is one of the best mass parties of the Communist International. It was one of the first to adopt without any reservations the principles of Communism. The Bulgarian Communist Party showed itself capable, as a member of the Communist International, of getting into closer contact with the oppressed working and peasant masses, of strengthening its positions and of defying the government of capitalists and village profiteers.

“The Executive of the Communist International expresses the hope that the Bulgarian Communist Party will carefully examine at its Congress its organisation and its political actions, in order to ascertain if they are commensurate with the demands which history places before the Communist Party. Participation in Parliament and in the municipal and communal councils must not be in the interest of petty reformist work, but must be used for the awakening and revolutionising of the masses. Such revolutionary action demands the establishment of illegal organisations, as we must expect at any time the destruction of the legal organisations by the bourgeoisie. Revolutionary actions do not drop from the blue and the conditions for them cannot be created only by agitation and propaganda. They come into being when- ever and wherever the party bravely endeavours to aggravate and extend every social conflict. It is only thus that the struggle for partial demands can be converted into a struggle for political power.

“This struggle for political power is easier in the Balkans because the bourgeoisie of these countries is not as well organised as that of Western Europe. The conquest of power by the working class and the poorer peasantry in a Balkan State would find an echo in every neighbouring State, for in the Balkans all the Governments are faced with great difficulties. Revolution in the Balkans does not mean only the emancipation of the Balkan working class from the yoke of capitalism and of the Balkan peasantry from the grip of speculators and usurers, it would also greatly accelerate the victory of the revolution in Central and Western Europe. Revolution in in the agrarian countries of Southern and Eastern Europe would greatly neutralise the peril which Germany and Italy are running in the event of them being shut off from the corn supplies of America. It would bring revolution nearer to the peoples of Asia who hitherto were touched by the revolution only through Russia.

“Trusting that in the knowledge of its great responsibilities the Communist Party of Bulgaria will be spurred on to greater efforts, the Executive wishes it success in its work.

“Long live the Bulgarian Communist Party!

Long live the revolution in the Balkan countries! Long live the Communist International!

Long live world revolution!”

You see that we did not deem it advisable to criticise, and limited ourselves to expressing our apprehensions in a very definite manner. Subsequently we discussed these questions with the Bulgarian comrades at many sessions of the Executive. I wish to remind you that at the time of the Greek revolution we spent five hours in arguing with Popov and Jordanov about the necessity of an advance by the Bulgarian Party. The representative of the Executive, whom we thereupon sent to Bulgaria, discussed these questions at various. sessions with the Bulgarian Party. We are justified in saying that we already realised the danger even at that time. We are to blame for our reluctance to interfere with the internal affairs of a big, old Communist Party, for having lacked the courage to tell the truth to the party and for not having sent into the old Central Committee, whose members are very good and highly educated comrades, workers who might have introduced into it a more revolutionary policy. We are to blame for having paid too much heed to the noise made about “ukazes from Moscow.” We are aware that we deserve this blame, and we trust that the Communist Parties will not only draw general tactical lessons from this situation in Bulgaria, but that these experiences (which will probably cost the lives of hundreds and thousands of proletarians in Bulgaria, and will perhaps retard the victory of the revolution for a considerable time) will teach them that we must lay aside this reserve of ours in the present critical period. We are convinced that we must be loth to interfere in countries where the situation is far from revolutionary, but that we must not stand back in the case of countries where the historic accomplishment of revolution is imminent.

I am absolutely convinced that after this experience, every Communist will understand if we brush all organisational scruples. aside and interfere in such a situation in the name of the Communist International. Wherever there is a danger of our party being smashed without striking a blow, and of Fascism triumphing, it is our task to remind it that it is the duty of every Communist Party which is a mass party to dare to fight, even at the risk of defeat. For even if it is defeated, which, in the given situation, is by no means a foregone conclusion, it will show to the working masses that they have a fighting centre around which they can rally as soon as the offensive abates and as soon as Fascism begins to disintegrate.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n26-27-1923-CI-grn-orig-cov-riaz-r3.pdf