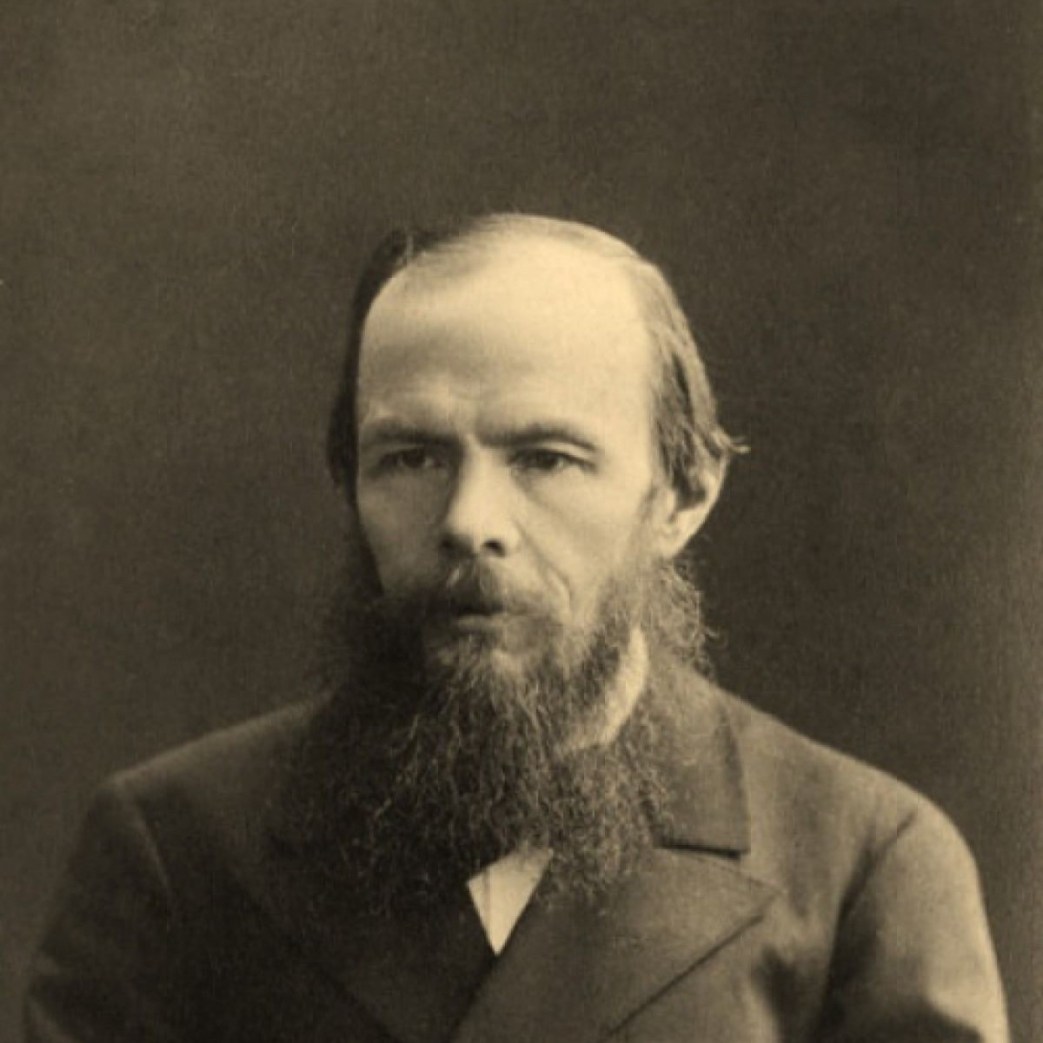

Floyd Dell, literary editor for New Review, The Masses, and the Liberator on the power of the Dostoevsky’s novels.

‘The Novels of Dostoevsky’ by Floyd Dell from New Review. Vol 3. No. 6. May 15, 1915.

IT is an experience of the first magnitude to read the novels of Dostoevsky. There has been nothing like them in the world’s literature–nothing so volcanically powerful, so searchingly true, so terribly and wonderfully revelatory. Their definite importation into the common stock of literature accessible in English, through the translations of Constance Garnett now being published at the rate of two a year by the Macmillan Company, is likely to be an event of significance in English is likely to be an event of significance in English and American literature.

Fiction can hardly remain the same after it has been touched by Dostoevskian influence. It is an influence which changes our sense of fiction values; it makes us demand as readers, and should make us desire to achieve as writers, those larger boundaries, those abysmal depths and terrific heights of experience which Dostoevsky’s art includes. It gives us a new sense of truth which makes the revelations of our standard English novelists seem paltry and insignificant. It must give a tremendous impetus to the fictional expression of the terror and beauty of life.

Somewhere in the early nineteenth century, people began to believe in civilization. They observed that the earth, the sea, and even in prospect the sky, were being brought under the control of man; they observed that there was a steady improvement in the machinery of production, brought about by invention, and in manners and morals, by law. They idealized this process, with the result that a great value was set upon seeming a little better this year than we were last year. Attention was centered upon a gradually improving mediocrity. The result in science was the popularization of the doctrine of “evolution.” The result in literature was the disappearance of the old-fashioned hero and the old-fashioned villain, and the centering of attention on the ordinary citizen, who was neither very good nor very bad, but just a little better than people were a short time ago. Extreme wickedness and extreme goodness went out of fashion in good literature. And this change of literary fashion reflected the current dogma that the human soul was really a respectable affair, something far, far beyond the savage, and aspiring only in a quiet evolutionary way to the sanctities of a utopian future. Such, indeed, is the view that most of us hold of ourselves today.

But a change is coming over us. We are beginning to wonder if after all it isn’t easier to be a savage or a saint, or both at once, than it is to be a respectable citizen. We are beginning to suspect that we are not really the respectable citizens that we seem, slowly evolving mediocrities, but a medley of violent extremes of good and evil. A science has already come forward, in the shape of Psychoanalysis, to teach us this. And so perhaps we are ready to learn the same thing from the novels of Dostoevsky.

Five of these novels have already been published in this series: The Brothers Karamazov, The Idiot, The Possessed, Crime and Punishment, and The House of the Dead. Of these, Crime and Punishment has indeed long been known to English and American readers as a profound study of the light and darkness of the human soul.

But one book alone cannot convey the Dostoevskian view of life. One book may leave the reader with the idea that he has been looking into a peculiar and “morbid” soul. It is only several of these books that can impress upon the reader that this peculiar and morbid soul is the soul of mankind. That fact–for under the conviction of Dostoevsky’s art one accepts it as a fact–is at first terrifying, then profoundly illuminating. One sees the soul of man as ever containing infinite possibilities of cruelty and infinite possibilities of love–one understands how, maugre our nineteenth century ideas of a gradually evolving mediocrity, life can still shape forth appalling wickedness and miraculous good.

Among these books, the latest one to be published, Dostoevsky’s House of the Dead, is not the most powerful, but it is interesting as showing how Dostoevsky got his insight into life. He got it in prison, where life both in its good and its evil stands most nakedly revealed. From these personalities, people who were under no constraint of pretending to be respectable mediocrities, who were perhaps in prison because they could not successfully make that pretense, he found out the truth–that the human soul is devilish and sublime. For in prison, as in the dreams to which the psycho-analysts go to learn the truth about human nature, all that is too wildly bad or good to fit in with our conception of what we ought to be, is found.

Dostoevsky’s novels have been called nightmares. But reflect that nightmares may be the clue to our self-deceitful lives. Under the pretty painted exterior of the ordinary soul may be the lightning-riven gulfs of Dostoevsky.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n06-may-15-1915.pdf