The T.U.E.L. needs a French-speaker to organize in New Jersey as hundreds of largely Breton-recruited workers strike at the tire plant in Michelin-owned Milltown.

‘The Milltown Rubber Strike’ by Tom De Fazio from Labor Unity. Vol. 2 No. 11. December, 1928.

THE recent brief militant strike of 1,200 rubber workers at the Michelin Tire plant in Milltown, New Jersey, is typical of the spontaneous, hotly-fought strikes of unorganized workers breaking out with increasing frequency under the lash of rationalization. Especially significant in this strike was the strong impulse toward organization shown by workers who had been kept carefully isolated in a company town from contact with the labor movement, and yet called for the formation of a union, at their first mass meeting following the walkout, before organizers had entered the situation.

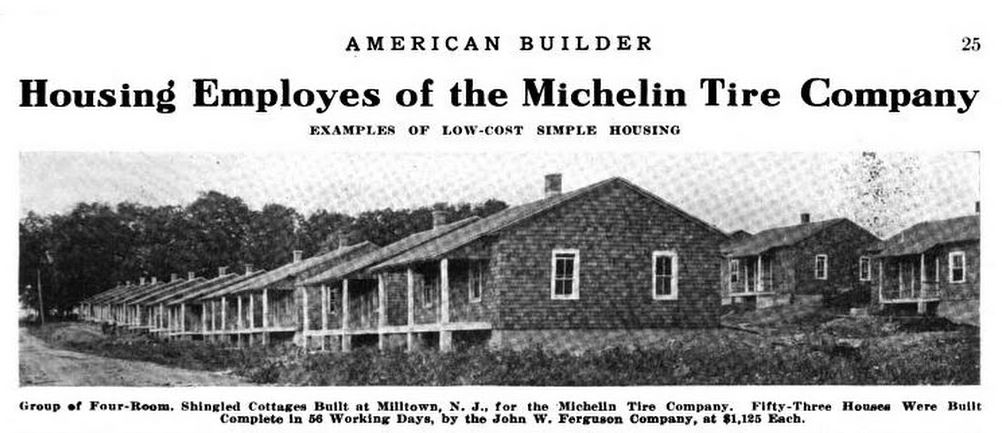

Milltown is a 100% company town after the manner of the feudal strongholds owned by Mellon and Schwab in the Pennsylvania coalfields. It is off the railroad, an hour’s ride by trolley from New Bruns wick, the nearest town, with one street, (Main street), and long grey squalid one-story wooden company barracks in the shadow of the plant, where the majority of the workers live under the wretched conditions imposed by their starvation wages. The halls are company controlled, and were closed to the strikers, who had to hold their meetings out in the woods off company property in November cold and rain. Mayor, sheriff and police act openly as watchdogs for the company in the same way as the squires and coal and iron police in mining territory.

Starvation Wages

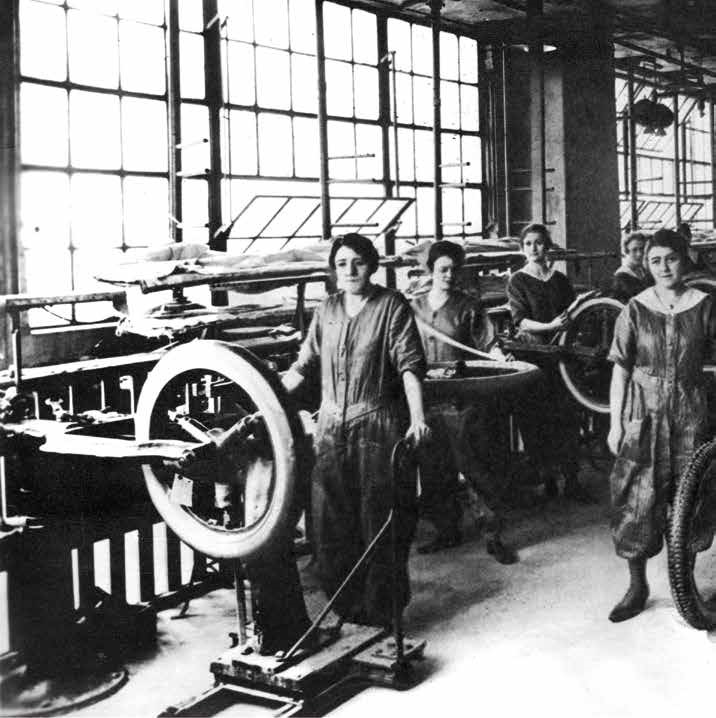

There are Poles, and some Hungarians and Greeks, but the great majority of the workers are French, imported direct by the company on an illegal contract basis, peasants and fishermen from Brittany, selected as less likely to revolt against exploitation than the city workers. Except for a few highly skilled mechanics, the men get from $13 to $20, including a “premium” used to speedup production, and the women, about 25% of the workers, as low as $10.00 Last year the profits of the Michelin Tire Company ran to over $6,000,000.

On Monday November 5th a wage cut of 3 1/2c to 5 1/2c an hour was put into effect, the third cut within recent years. The workers, unorganized and leaderless, struck, 100 solid except for a few of the higher paid skilled mechanics, also forced out as the plant ceased working. The strikers massed around the plant in rough picket lines, some, who had seen demonstrations in France, sang the “Internationale.”

T.U.E.L. Enters Field

The T.U.E.L. learning of the strike situation, sent in Tom De Fazio, and Sam Brody, French-speaking organizer. Picket lines grew, and by Thursday, the police made its first attack on the line, beating up two of the leading strikers. The clash with the police only increased the determination of the strikers to organize, and a spirited meeting was held out in the woods in the pouring rain. Demands were put forward for: (1) Immediate restoration of the wage cut, and a 10% increase; (2) Recognition of the union; (3) No discrimination because of strike activity; (4) Safeguard against poisonous fumes, etc.

Alarmed by this unexpected resistance the company offered to cut the reduction in half. The strikers unanimously rejected the proposal.

Then Henry J. Hilfers, organizer of the American Federation of Labor appeared on the scene summoned by the company to combat the T.U.E.L. leadership and the sellout began. At the last convention of the New Jersey State Federation of Labor, Hilfers, was found guilty of accepting thousands of dollars in bribes from manufacturers for “protection,” in his capacity of secretary of the Federation. Hilfers was removed, and later appointed representative of the national A.F. of L. organization for New Jersey. He has a long record of strikebreaking and corruption throughout the state, including an attempt at strike-breaking manoevres in the Passaic strike, and at disrupting the Furriers union in Newark.

On his arrival, Friday, Hilfers immediately went into conference, not with the strikers, but with the plant superintendent, the sheriff and the mayor. That evening a sharper attack was made on the picketline than the previous day, the special target being the French T.U.E.L. organizer, Brody, who was so badly beaten that he was disabled for the following week. Hoffman, the Hungarian militant beaten the day before, was slugged and thrown into à car and taken to the county jail. “Get out of town and stay out of town” was the sheriffs ultimatum to the T.U.E.L. organizers.

A.F. of L. Betrayal

Hilfers began calling meetings, being given the use of the company-controlled halls closed to the T.U.E.L. organizers. He sent stoolpigeons among the strikers, advising them to go back to work on the compromise half-reduction. The demand for organization he met by telling the workers the A.F. of L. would build an organization inside the mills after their return. He worked to weaken the strikers’ morale by telling them the company would bring in scabs from outside if they refused to go back; “There are others in other towns to take your place” he told them at a meeting, working on their fear of being stranded jobless, strangers in a strange land. The T.U.E.L. he denounced as swindlers, Bolsheviks and Communists, flourishing A.F. of L. documents and representing himself as the only one with a “legal right to carry on organization in New Jersey.”

The more conscious elements sized up Hilfers immediately. As one of the leading strikers put it: “We have no interest in people who organize from Michelin for Michelin.” Another said: “Hilfers says you are Bolsheviks, Communists. Well, if Communists can organize us, let them organize us.”

But many, inexperienced in labor battles were disheartened and confused. Both A.F. of L. and T.U.E.L. were new to them, and though the few who knew the ways of labor fakers from the past summed up the situation correctly, the majority lost all confidence, not knowing whom to trust, Besides the T.U.E.L. organizer, still ill, had not returned, and English was a strange and hostile language.

On Tuesday, the 13th, Hilfers called a meeting and announced that the “strike committee’ formed from his followers, had decided to end the strike the following day. Two hundred of the most militant strikers were informed that they were laid off. One had worked in the plant for 19 years.

Wage Cut Stands

Returning, the workers found that Hilfers had deliberately lied to get them back to work. The full cut stood, and the company had no intention of returning 50%, as Hilfers had repeatedly told them. The statement about building a union after the strike was equally false. Hilfers vanished from the scene after his job was done.

Many of the workers who were hesitant while the strike was on, declare that now they realize the strike-breaking role the A.F. of L. has played, and are turning to the T.U.E.L. for organization, though the company threatens to have all those joining the “Bolshevik” union deported. The T.U.E.L. is planning an intensive organization drive among the Michelin workers, as well as those employed in other rubber companies located in that section of New Jersey.

Labor Unity was the monthly journal of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), which sought to radically transform existing unions, and from 1929, the Trade Union Unity League which sought to challenge them with new “red unions.” The Leagues were industrial union organizations of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the American affiliate to the Red International of Labor Unions. The TUUL was wound up with the Third Period and the beginning of the Popular Front era in 1935.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labor-unity/v2n11-w30-dec-1928-TUUL-labor-unity.pdf