A fantastic piece by Frank Bohn about a city he was well familiar with; Youngstown, Ohio where a 1916 strike against Republic Steel saw a massacre of workers, and a righteous, incendiary vengeance.

‘Fire in the Steel Trust’ by Frank Bohn from The Masses. Vol. 8 No. 5. March, 1916.

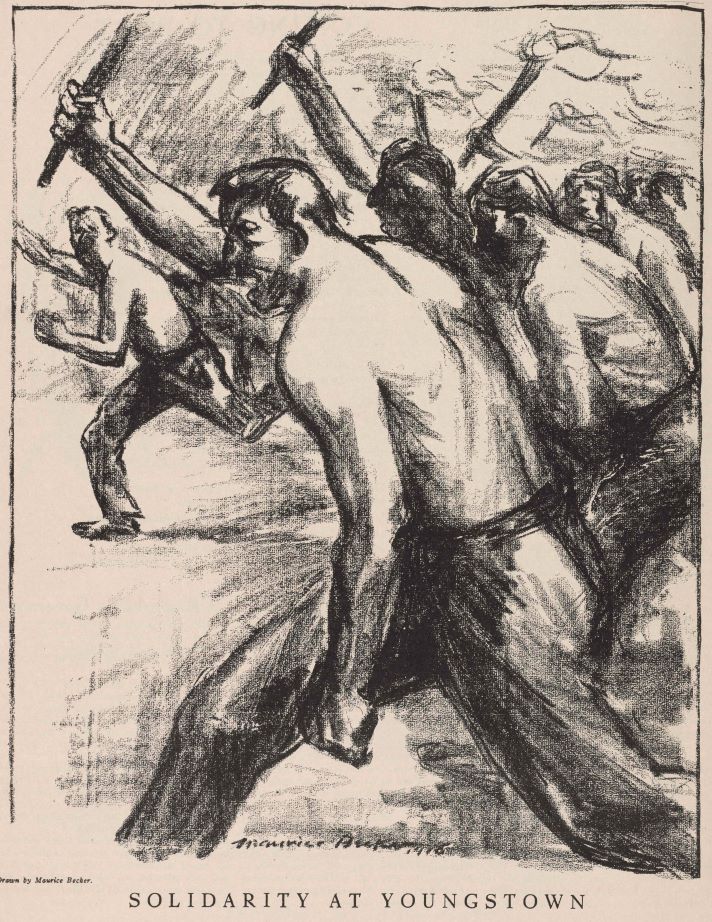

IT was a real battle–not a ridiculous piece of medievalism such as is now going on in Europe. It was a Twentieth Century conflict such as is becoming a familiar story in the newspapers. The unarmed militia of the working class, like the forces of Jackson at New Orleans a hundred years ago, won a qualified victory from the organized and disciplined army of capitalism.

“No, I tell you, I never see anything like it. I was there in Pittsburgh in ’77 among the railroad men. Somebody filled an engine and five cars full of oil, set it afire, and run it forty miles an hour into the round house where the Pinkertons was livin’. But this East Youngstown business! In my forty years a’ strikes an’ strikers I never see the like. It was a patch a’ hell sizzlin’ in its own juice.”

I had just come to town and a few old friends were entertaining me in the “Puddlers Saloon.”

Another one of the old ones agreed heartily with the view already expressed. “It looked at first,” he said very quietly, “as though the golden dreams of my youth had come true. I had read in the labor papers about such things as twenty thousand unskilled, unorganized men coming out on strike and standing together like a rock, but I had never imagined what it was to see it with my own eyes. I too have waited a long time. I was slated to make a speech from the wagon in Chicago in 1887 when the ‘stool’ pitched the bomb. When I heard it blow of course I skedaddled. I run home and says to the wife–I says ‘We K. of L. officials has got to cut the town.’ I went on a train with over a hundred others and we dropped off any old place on the prairie. At three the next morning the Pinkertons and the Police came to my house to arrest me. Well, those times is gone and the real fight is on at last.”

The Might of the Mass.

The Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company employs 15,000 men. Two-thirds of these were unskilled and they received 19 1⁄2 cents an hour before the strike. This concern spent $7,000,000 in improvements last year. Its common stock since the war started has risen from $5 to $40. Not a single group of workers received a cent increase. On December 27th 10,000 “Hunkies” struck. Two weeks later they carried the 5,000 skilled and semi-skilled on and up for a ten per cent. increase. The Republic Iron & Steel Company employs 9,000 men and the Carnegie Steel Company, which is part of the Steel Trust, has 10,000. All these received a flat ten per cent. increase.

Thirty cents a day more might not seem very much to a New York bricklayer, but the steelworker in Youngstown has literally starved on his 19 1⁄2 cents an hour. Three dimes more a day has given him a taste of victory–which is more to be desired even than a taste of fresh meat.

Before the strike the craft unions did not have a single organized group of workmen in the steel industry. Since the strike a half dozen organizers, machinists, pipe-fitters, etc., have been here on the job, successfully organizing their crafts in every steel mill in Youngstown.

Youngstown.

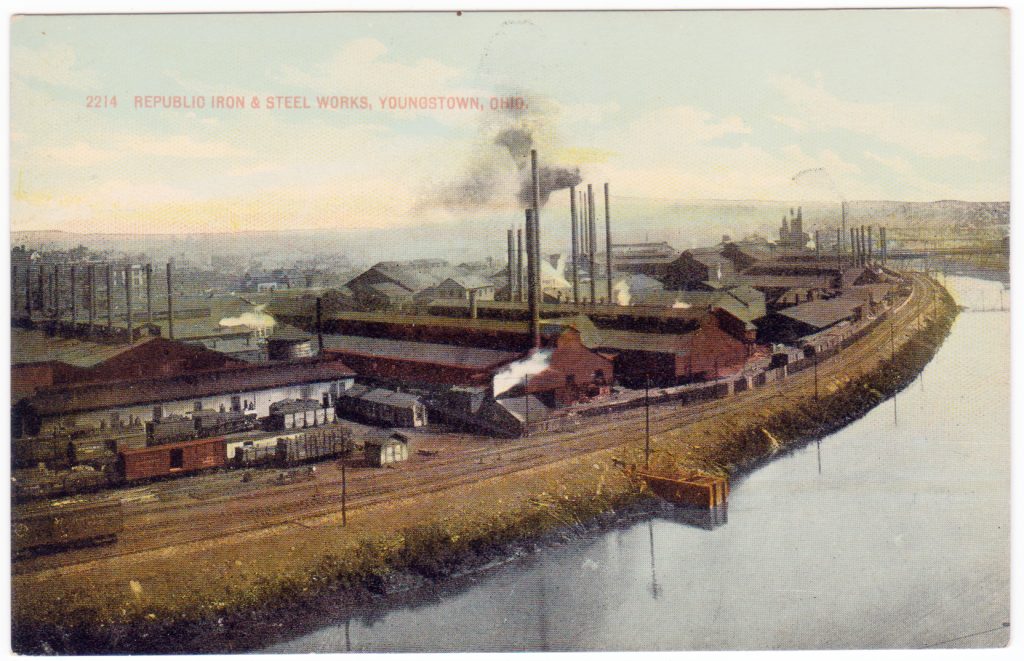

To get a view of Youngstown fixed in your imagination, conceive on the horizon fifteen miles distant a dark and ugly cloud. If it is night, this cloud is illuminated by flashes of fire. You come closer and at last into the clouds–you are among the suburbs of this workshop of 110,000 inhabitants. On one side the mills of The Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company occupy exactly four miles of the Valley of the Mahoning River. Above it is the Republic Iron & Steel Company. On the other side are hundreds of acres of dingy shacks. You conclude at once that they are the cheapest and meanest habitations occupied by human beings in the whole world.

The central part of the town is like other American industrial cities of its size. A few thin skyscrapers shoot up at intervals. There is a beautiful new post-office paid for by the Federal Government, of course. There is one good hotel. Citizens tell you that the new courthouse cost just two millions of dollars. The rear wall and top story made of cement blocks are already cracking to pieces. Everywhere smoke-dirt-dust-mud-grime. Prosperous looking businessmen with dirty faces and dirty hands and dirty linen. Everybody breathing dirt, eating dirt–they call it “pay dirt,” for Youngstown clean would be Youngstown out of work and out of business and starving to death. So dirt is the one essential part in the life of the community. Everybody loves it.

The Strike.

On December 27th fifty pipe fitters in the Republic Iron & Steel Company struck for an increase of 25 cents a day and won in about five minutes. The news was too good! Two hundred laborers went out in a body for 25 cents a day increase and began to picket the gates. They “made it stick.” Skilled and semi-skilled couldn’t work without the Hunkies. Then, too, the skilled were not averse to an increase them- selves. On the third and fourth day the furnaces were stopped–which is the essential thing in an iron and steel strike.

On January 5th the Electric Shock of the real thing ran along the lines of the strikers’ army. Its sure sign was the battle cry, “General Strike.” Nobody knows who started it. There has been a small Slavic Local of the I.W.W. at Youngstown. A dozen or more A.F. of L. organizers, Craft Unionists and general headquarters men had come to town. Probably no organization and no individual was responsible. It was instinctive. Crowds of strikers moved upon the Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company plant. Voluntary committees organized themselves and went to New Castle, to Sharon and to Niles. Their demands had focalized–25 cents an hour minimum for a ten-hour day, time and a half for overtime and double time on Sundays and holidays.

The officials of the Steel Trust, who manage the Carnegie Steel Company at Youngstown, were wise. They saw what was coming and at once posted bulletins informing their workers that 22 cents an hour for unskilled labor would be the rate after February 1st and that everybody would get a 10 per cent. increase.

Jim Campbell Wants the Militia.

The dominant mind among the employers was Mr. James Campbell, president of The Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company. “Jim” Campbell is a perfect representative of his class-the “self-made” American Capitalist. From a clerk in a flour and feed store he has become the employer of 15,000 men in a town of 110,000 men, women and children. “Jim” Campbell usually has his way about most everything in Youngstown. Now the mind of “Jim” Campbell worked quite as correctly as that of the strikers. The strikers kept saying to one another–“Keep together, stay in bunches; if 20 of you speak 17 different languages, make motions and laugh and shout. Everybody come out night and morning when shifts are changed. Speak sweetly to the men who are going to the mill and plead with them with tears in your eyes to join your forces. If that doesn’t help, try some other method, but keep it up.” As a matter of fact nearly everybody had come out of the shops, except stationary engineers and firemen and the clerks, who kept up a bluff of work among the furnaces.

“Jim” Campbell said to his colleagues that crowds would have to be dispersed that the assembling of crowds meant success for the strikers, that what they wanted was a full brigade of militia, 2,000 strong, who would keep East Youngstown swept clean of “disorder” and “lawlessness.” They appealed to the Governor through the local authorities.

On Friday morning Adjutant General Weybrecht came from Columbus and looked over the situation. He went into conference with Mayor Cunningham, the Sheriff, “Jim” Campbell and other capitalists. In that conference he declared that the militia was not needed and that he was going back to Columbus.

“The militia not needed,” shrieked Campbell and his distinguished fellow citizens–25,000 men asking for a twenty per cent. increase in wages and the militia not needed. What are we supporting the militia for, anyway?

The Massacre.

In the afternoon there was another conference without the Adjutant General. That conference closed at 4:30. At five o’clock about 200 strikers were in the vicinity of the bridgehead on the raised street, from which the employees cross the bridge over a dozen railroad tracks to get into the plant. Six company guards, armed with repeating rifles, came out and took up their station on the bridge. There was not a single striker on the bridge, which is company property. They were in the public street. It was the orthodox Greek and Russian Christmas. The strikers had been celebrating by parading in quaint costumes and feasting in their homes. There were thousands in the streets who were not specially interested in picketing on such a holiday.

The six company guards first raised their rifles and fired one shot over the heads of the pickets, who refused to retreat. The guards then emptied their repeating rifles into the crowd. They were at a point blank range–not over forty feet away. Forty dead and dying men fell to the ground.

The Fire of Revenge.

Probably every striker in East Youngstown was on the scene within ten minutes. What they accomplished was told in headlines throughout the country next day. The guards retreated to the far end of the bridge and took cover. It was impossible for the strikers to get into the mill or lay hold of the guards.

Their action was absolutely instinctive. Society had committed treason and murder against them. In their power was a half million dollars’ worth of property, about which was thrown the guarding power of the sanctity of the law. They took such revenge as the situation made possible. Here, unprotected, was the bank and post office, an office building or two and a dozen considerable stores. Scattered among these were a score of smaller buildings. The mob made no distinction. It threw dynamite through the windows and doors and retreated long enough for the fuses to set it off. A shoe repair shop owned by a Slavic Socialist and strike sympathizer went with the rest.

“How could they dynamite the bank?” asked an astounded and perplexed small businessman. “Didn’t they have their savings in it?”

Mr. Jim Campbell got his militia the next morning–two full regiments of them. There was no more picketing, no more crowds on the street. Every informed working man in Youngstown knows that 25 cents an hour would have been secured had it not been for the “riot” and fire.

The “riot” and fire lasted from 5:15 in the evening until one o’clock in the morning. The East Youngstown police ran away. At two o’clock the next morning, when the streets were deserted except by a few drunks, a posse of brave citizens moved like ghosts among the ruins and drove the few remaining intoxicated men away from the beer cases and whiskey casks which had been carried cut of the burning saloons and piled in the open. This act of heroic public service has resulted in a rancorous debate as to who is to be first in public esteem and praise. The argument resembles that between the friends of Sampson and those of Schley after the battle of Santiago. City Solicitor E.O. Diser says that he did it. He will be rewarded with nothing less than Republican Nomination for Congress. His claim is disputed by the friends of the Honorable Mr. Martin Murphy, democrat and former constable of East Youngstown.

East Youngstown has 8,000 inhabitants and 400 voters. The kind of government resulting therefrom may be imagined. “Justices of the Peace,” when they fine a prisoner $5.00 and costs, are permitted by law to pocket $3.95 of the five dollars. Before the strike a foreign working man was arrested for “trespassing” on the railroad track while going to work: “a dollar and costs,” said the Justice. The laborer had just been the recipient of a month’s pay and in his innocence he drew out a twenty dollar gold piece. The Judge saw the coin and quickly changed the fine to twenty dollars and costs.

Professor Faust Reaps a Harvest.

In Youngstown there is a principal of a school known as Professor Faust. The Professor lacks none of the philosophic qualities of his great namesake. But, of course, modern industrial America has changed the means of expression. The Faust of classical lore never had such an opportunity as came to the Youngstown savant.

For Professor Faust has just recently been elected Justice of the Peace.

After the militia came, the police returned to town and under their protection arrested some three hundred strikers. The cells were packed and Prof Faust held court in the county jail. He came close to his game for fear some might escape him. There was no jury impaneled. There was no evidence taken. No witnesses were called. Whether the prisoners had been present or not in East Youngstown during the riot and fire did not concern the “Court.” Only one distinction was made. Those who had lawyers to defend them were fined $1.00, $2.00 and $3.00 apiece. Those that came before the Professor undefended were fined from $10 to $50 apiece. During the four days that followed the strike, Prof. Faust’s share of the fines amounted to more than a year’s salary as Principal of Schools. It amounted to exactly 1,648 units of the coinage of these United States of America–each one of the sixteen hundred and forty-eight bearing on the one side the insignia “Liberty,” and on the other side “In God We Trust.”

The advocates of “law and order” in Youngstown thought that the “fair name of their city” would not be clean of the aspersions cast upon it by the newspapers of Akron, Canton and New Castle unless at least a hundred strikers were sent to the penitentiary, but the big employers wouldn’t listen to this. Workers are mighty scarce these days, and “Jim” Campbell and his colleagues didn’t care a rap about the small businessmen who lost their little all in the fire. Three days after the strike the Youngstown newspapers began to say that the community was more or less responsible for what had happened, that the “poor working people” had never been brought close enough to the tender bosom of the community. As soon as magnates began to talk about the dangerous scarcity of labor and to express fear that foreign working people from other towns would be kept away by drastic action, the Youngstown Indicator began to editorialize in answer to the question as to what “Christ would do to the striking workers if he came to Youngstown.” So, although there are still over a hundred workers in jail, some of them everyday are enabled to borrow the amount of their fines from loan sharks. In the end probably not more than fifteen or twenty of them will have to go to the penitentiary.

NOTE.-As I am hurriedly completing this statement, the attorney for several of the men in jail calls and informs me that the prosecuting attorney is selecting the Socialists and I.W.W. members for criminal prosecution–that not the slightest effort had been made to arrest a single company guard, and that nothing would be left undone in the way of furnishing “an example” to future strikers. “The Iron Heel,” says their attorney, “is coming down on their necks.”

The Masses was among the most important, and best, radical journals of 20th century America. It was started in 1911 as an illustrated socialist monthly by Dutch immigrant Piet Vlag, who shortly left the magazine. It was then edited by Max Eastman who wrote in his first editorial: “A Free Magazine — This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers — There is a field for this publication in America. Help us to find it.” The Masses successfully combined arts and politics and was the voice of urban, cosmopolitan, liberatory socialism. It became the leading anti-war voice in the run-up to World War One and helped to popularize industrial unions and support of workers strikes. It was sexually and culturally emancipatory, which placed it both politically and socially and odds the leadership of the Socialist Party, which also found support in its pages. The art, art criticism, and literature it featured was all imbued with its, increasing, radicalism. Floyd Dell was it literature editor and saw to the publication of important works and writers. Its radicalism and anti-war stance brought Federal charges against its editors for attempting to disrupt conscription during World War One which closed the paper in 1917. The editors returned in early 1918 with the adopted the name of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, which continued the interest in culture and the arts as well as the aesthetic of The Masses/ Contributors to this essential publication of the US left included: Sherwood Anderson, Cornelia Barns, George Bellows, Louise Bryant, Arthur B. Davies, Dorothy Day, Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, Wanda Gag, Jack London, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Inez Milholland, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Carl Sandburg, John French Sloan, Upton Sinclair, Louis Untermeyer, Mary Heaton Vorse, and Art Young.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/masses/issues/tamiment/t59-v08n05-m57-mar-1916.pdf