Rivalry between French and German imperialism in West Africa, a new tax on women merchants, and an uprising.

‘The Native Revolt in Togoland’ by Nandi Noliwe from Negro Worker. Vol. 4 Nos. 2 & 4. June & August, 1934.

In order that we may understand better the causes of the rising, which broke out on the 25th of January 1933 in Lome (the capital of French Togoland), it will be useful to give a brief outline of the history of how France received its mandate for Togoland, and bring to light the developing imperialist contradictions, describe the economic position and uncover the consequences of the crisis which led to a more or less stormy and spontaneous explosion of the people’s discontent.

THE PARTITION OF TOGOLAND.

The first partition of the German colonies in Togoland and the Cameroons, that had been conquered and occupied by the allied troops, was effected on the basis of the agreements of the 30th of August 1914 and the 4th of March 1916. According to the agreement of August 30th 1914, the government of a large part of Togoland was vested in the government of the Gold Coast. The ports of Lomé, Misahohea, Kete-Kratchi (Middle Volta) and, finally, a part of the territory on the Upper Volta–Yendi, were placed under its jurisdiction.

Insofar as Lomé and a large part of the railways thus proved to be in the hands of the British, France started fresh negotiations, trying to secure a new division of Togoland. Lord Milner (the State Secretary for the colonies) and Henry Simon (the Colonial Minister) signed two documents on the 10th of July 1919 in Londen, which established the frontiers separating the territories of Togoland and the Cameroons. Thanks to these new frontiers, France received, besides the ports of Lomé and the Misahohe region in the south, also the undoubted right to a whole number of important villages and acquired, besides this, the entire road from Lomé to Atakpamé. Despite the fact that Togoland and the Cameroons were already actually divided among Great Britain and France, their mandates were only officially recognised by the council of the League of Nations on the 20th of July 1922.

Article 9 of the final draft reads that France “receives the unlimited authority in the government, legislation and jurisdiction in the countries for which it has mandates.” And so, it may divide the territories, under its mandate, in districts and administrative units; it may set up on its territory fiscal, customs and administrative unifications; finally it has the right to organise municipal services, establish a TAXATION SYSTEM and form a local police. The government of the territory is effected through a Commissar of the Republic, an Administrative Council and a Judicial Administrative Council.

RIVALRY BETWEEN THE FRENCH AND GERMAN IMPERIALISTS.

It goes without saying that German Imperialism considers that its interests have been injured by the annexation of the territories of Togoland and the Cameroons. Taking advantage of the discontent of the broad masses of the population, which arose as a consequence of the economic crisis and the frightful fiscal pressure, under which the natives are groaning, the “Bund der Deutsche Togolaender” (the Union of the German Togo Provinces) is carrying on an active campaign for the return to Germany of the colonies in Togoland which belonged to it before the war.

In an open letter (published on the 18th of February 1933 in the “Gold Coast Spectator” to De Guise, the French Governor of Togoland, one of its inhabitants bitterly complains that a whole number of posts are banned for the natives under the French Government. He says that the natives are “walking the streets without work” and that all the impositions and taxes on incomes are completing the ruin of the population which had already been so hard hit by the crisis.

Feeling uneasy at these pro-German declarations, France, in its turn, answers with an open letter in the name of a French inhabitant of Togoland, in which he describes the “cruelties” of the German regime in Togoland and the “blessings of French civilization.” The meaning of this polemic between the imperialists is quite clear to us! Under cover of these letters, signed by «natives», the French and German capitalists are fighting for markets for the export of their industrial manufactures and import of the raw material from this country. Whether German “civilization” stands on a higher or lower level than French, is truly, a question of not the slightest interest to the native workers, since even though the methods may differ in one respect or another, the results are in any case the same! What follows quite obviously from all this is that the native workers are crushed under the weight of taxation with which. they are burdened by the French Government, so that it may find an outlet from the raging crisis in the motherland, and so that France may compensate itself for the losses it suffered in its commercial deals with other imperialist powers.

The French mandated territory of Togoland is one of the most hard hit by the world economic crisis. All privileges which had been formerly granted to the native officials have since been suppressed; the cutting down of salaries on a mass scale, the tremendous increase in taxation which has been going on since 1930 along with a catastrophic drop in the prices of raw materials; the introduction of a new taxation system on native medical assistance, 6,000 unemployed out of the total population of 750,000 all this contributed to create in the country an atmosphere of general and bitter discontent on the part of the natives.

However, despite this growing discontent, the French administration went as far as to levy new taxes. First, a general increase in taxation was decided the poll tax was raised from 40 tot 50 francs for the lowest category, and from 128 francs tot 318 fr., for the highest one.

A new tax was also decided on the native merchant-woman, and this was the last drop into the already over filled cup. One must not forget that when France took the mandate over Togoland it was decided that:

“Since the German administration had exempted women from taxation in Togo, Cameroun and other German colonies in Africa France should not show herself meaner than Germany and, consequently would not tax women.”

The whole population got alarmed when it was decided to tax women also. The “Conseil des Notables” met and decided to circulate a petition list and send it to the Minister for the Colonies, to protest against such a burden of taxation.

Two of them were arrested and put in jail. It was then that the population, wild at this last provocation, organised a demonstration. On the afternoon of January 24th, 1933, women, children and unemployed came out into the streets. Despite the police forces they went right into the Administration buildings of Lomé and even as far as the gates of the Palace of the Commissar of the Republic, asking for the immediate re lease of the two imprisoned men. The General Secretary of Finance of Togo–Mr. de Saint-Alary–declared then that they “deserved to be shot down”! But in spite of all and under the pressure of the crowd thus gathered, the administration was forced to order that the two constables be released.

However, on the next day, a general strike was organised by the merchant women. All shops were closed down in the market and the life of Lomé seemed paralysed. A restless crowd filled the streets of the capital. But while the Commissar of the Republic–Mr. De Guise–was officially promising that no new taxation would be carried out and that taxes would be left as of 1932, he was, at the same time ordering extra troops from Dahomey and the Ivory Coast. Then an unprecedented reign of brutalities, exactions and terror against the natives started.

BUTCHERY AND MAN-HUNTING.

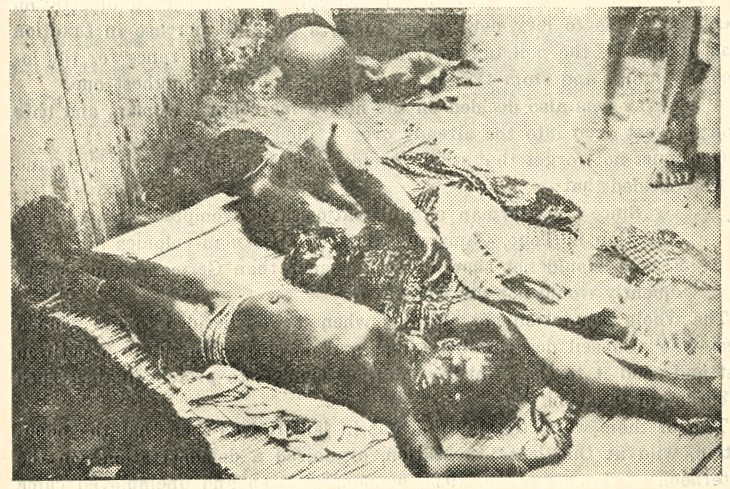

Although calm had been long since restored, the troops were called in to organise a real butchery and man-hunt in the native district of Ahalnucope on February 4th. The defenceless and peaceful natives were shot down–9 were killed and two severely injured. Among the dead were one woman and a child (see picture). Besides, this man-hunt continued and 150 were arrested without any reason.

The official explanation for such an unjustifiable repression given in the official Press was that “A soldier went mad and shot the people”, which was, of course, a shameless lie.

Although it might seem that, after such a terrible bloodbath, the French Government would have stopped the repression, nothing of the kind happened. On the contrary, the League of Nations (officially entrusted to defend the mandated territories) paid no attention whatsoever to the various complaints and telegrams for mercy sent from Togo. The taxation burden is, in fact, still being increased. And to the ruthless exploitation of the white oppressors one must add the native chiefs who also contribute largely to the exploitation of the poor natives. They recruit them, just when and as often as they like, for their own private work without paying them, or, if the natives do not obey they just fine them, for instance 7 or 8 francs. Besides this, they also raise out of their own authority special taxes on some villages and fine the inhabitants sums amounting sometimes to 250-500 francs.

To this, not only do the white administrators pretend to be blind, but they actually, quite often, share in this robbery. It has been officially admitted that the administration of the district of Porto-Nuovo received not less than 3,000 francs from the chief he had assisted in nominating.

All this shows to the oppressed native masses, clearly enough, on whom they can depend for help in their struggle against exploitation.

On the one side, they have seen with their own eyes what the so-called “peace institution” of the League of Nations has done to rescue them, and they are daily convinced that the majority of their own chiefs are not only mere puppets, but as well direct oppressors of their own countrymen and work hand in hand with the white rulers to drain them to the very marrow of their bones.

On the other hand, they have seen, also, during this last revolt what solidarity means when women, men, children, unemployed presented a united front against abuses and oppression. This page in the history of the long downtrodden natives will not be wiped out so quickly. The women themselves have now also awaken and though this short and spontaneous uprising was crushed down in blood, the poor and exploited haven’t felt, nevertheless, their own strength and must learn to co-ordinate it so as to reach the final goal: the unconditional independence of their country.

First called The International Negro Workers’ Review and published in 1928, it was renamed The Negro Worker in 1931. Sponsored by the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW), a part of the Red International of Labor Unions and of the Communist International, its first editor was American Communist James W. Ford and included writers from Africa, the Caribbean, North America, Europe, and South America. Later, Trinidadian George Padmore was editor until his expulsion from the Party in 1934. The Negro Worker ceased publication in 1938. The journal is an important record of Black and Pan-African thought and debate from the 1930s. American writers Claude McKay, Harry Haywood, Langston Hughes, and others contributed.

Link to full PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/negro-worker/files/1934-v4n2-jun.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/negro-worker/files/1934-v4n2-jun.pdf