West Virginia’s relationship with the rest of the country is unique. Labor Research Association investigator Anna Rochester traces the money and names the names of capitalist interests in the West Virginia’s coal fields. An essential document for understanding that reality, this will be of interest to all students of West Virginia’s militant miners’ history.

‘West Virginia Battleground’ by Anna Rochester from The Daily Worker. Vol. 5 Nos. 269 & 270. November 13 & 14, 1928.

Record Coal Producing State, Leading Union Crusher, Challenges New Union

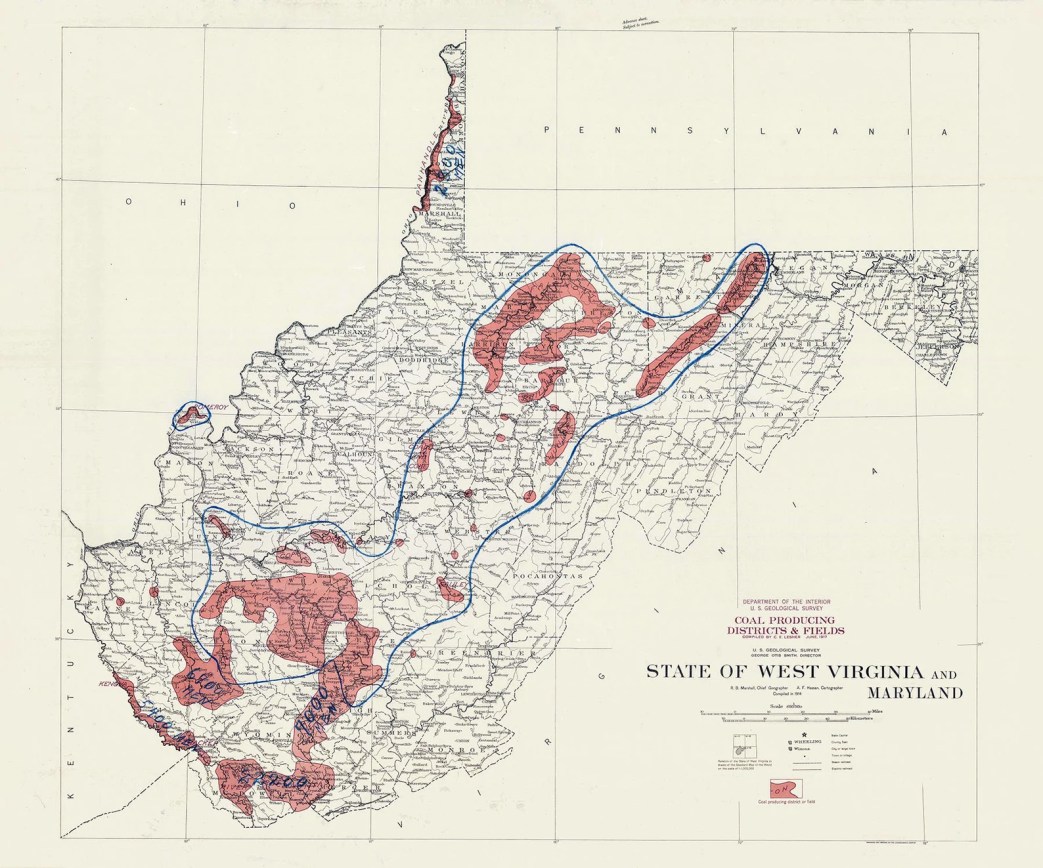

WEST VIRGINIA, the coal state now with the longest and bloodiest record for union crushing, holds the record also for producing more soft coal than any other state in the country.

Pennsylvania had held the lead for a hundred years. Even ten years ago West Virginia mines were turning out only half as much soft coal as Pennsylvania mines, but since the war Pennsylvania production has been falling and West Virginia production has been rising. The strike of 1927 in the northern fields gave a final push to shift the balance between these two states. Since the strike was broken the Pennsylvania output has risen slightly and the West Virginia output has dropped, but the latest government estimates to October, 1928, show West Virginia still holding the lead.

Along with this the number of West Virginia miners has increased and the number employed in Pennsylvania mines has dropped. But even if West Virginia mines had drawn all their new workers from Pennsylvania–and of course they have not done so–they would not have absorbed all the miners thrown out of work in the northern fields.

For West Virginia mines have on the whole more modern equipment than Pennsylvania mines. In 1927, the coal cut by machine was 83 per cent of the total in West Virginia and 66 per cent of the total bituminous in Pennsylvania.

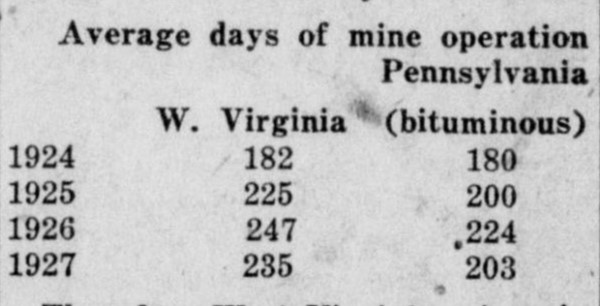

And since 1924 the West Virginia mines have been more steadily operated than the Pennsylvania mines.

Therefore West Virginia mines in 1927 turned out their 145,000,000 tons with about 120,000 men, while in Pennsylvania the 133,000,000 tons were mined by about 154,000 men. West Virginia coal mines have other distinctions also. Of the leading seven coal states West Virginia has had steadily the highest death rate from mine accidents. From 1916 to 1925 the average annual death rate from mine accidents (as computed by the U.S. Bureau of Mines, with adjustment for irregularity of employment) was 61.5 per 10,000 mine workers in West Virginia and 32 per 10,000 mine workers (soft coal) in Pennsylvania. Colorado and certain other less important coal states have had fatal accident rates even higher than West Virginia, but the hazards in West Virginia have been far greater than in the other leading states: Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Illinois, Alabama, Indiana, or Ohio.

The low wages in southern mines are also proverbial. For a brief period during the war boom West Virginia miners are said to have earned more than miners in Pennsylvania, but the conservative U.S. Coal Commission in 1924 assembled a mass of material showing that wage scales in the unorganized states were far below the scales in the union fields. The same thing appears in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports on mine wages.

For every reason, one of the most urgent tasks of the National Miners’ Union is the winning of these unorganized West Virginia miners. The task is also most difficult. For a generation or more, the West Virginia operators have been assembling and perfecting their weapons against the union.

Their first weapon is the yellow-dog contract. Operators reckon that this is sufficiently intimidating to keep the workers from starting “trouble.” But its chief usefulness is the handle it gives the courts for issuing injunctions against union activity by outside organizers. The famous Hitchman Coal Case, in which the United States Supreme Court in 1917 upheld the lower courts for the operator and against the union, had originated in West Virginia in 1907. John Mitchell, then president of the United Mine Workers, and other union officials were the defendants in the case. The courts held that union officials could be enjoined from all efforts to organize the company’s employes because the men had signed individual agreements with the company that they would not join the union.

The next weapon against unions is the company village policed by company employes. Company leases frequently forbid the miners to have strangers visit their homes. Company police in many villages challenge every unfamiliar face and send out of town anyone who cannot prove that he is an employe or a visiting salesman or preacher armed with a pass from the company office.

Yellow-dogs and company towns and coal and iron police have their own history also in Pennsylvania, and the isolation of the company village is bad enough there. But in West Virginia the miners are more successfully isolated than in Pennsylvania. The villages are more remote. There are few large towns, and coal is the one important industry in the state. The blacklisted miner in West Virginia has even greater difficulty than the miner elsewhere in finding other work.

Another weapon of West Virginia operators has been the corruption of union leaders. Three times in the past twenty years officials of the U.M.W.A. have left the union to work for associations of operators in West Virginia. D.C. Kennedy, for a short time president of District 17, went openly onto the pay-roll of the Kanawha operators in 1904. Tom L. Lewis, International president, in 1914 became secretary of the New River Coal Operators’ Association. And, as Foster puts it in “Misleaders of Labor,” “working in this treachery with Lewis is E.G. McCullough, formerly vice president of the U.M.W.A.” Foster tells also how Dean Haggerty withdrew relief in the midst of the bitter Cabin Creek strike, and later became himself an operator in this anti-union field.

In West Virginia perhaps more boldly than elsewhere, the operators have commanded the machinery of government against the workers.

And yet West Virginia miners have repeatedly revolted. Before 1890 struggling local unions had led local strikes in various parts of the state. In 1887, some 20 mines in Kanawha County went out together. West Virginia delegates attended the conference which organized the United Mine Workers in 1890, and two years later some 3,000 mine workers in the Fairmont field were out for three months, demanding union recognition and reinstatement of men discharged for union work. In 1894, two big strikes involving nearly 10,000 men spread through the Kanawha and Panhandle districts. The big strike of 1897 in the northern coal states–of what was then coming to be called the central competitive field–pulled out great numbers also in West Virginia.

Even in those earlier years the West Virginia strikes were bitterly fought. Strikebreakers were more generally brought in than they were in northern states, and a high percentage of the strikes were lost.

With the turn of the century there began the historic battles for union: at Stanaford in 1902, in the Paint Creek and Cabin Creek districts in 1912, in Logan and Mingo Counties in 1919. The Fairmont and Kanawha fields joined in the great strike of 1922.

The operators’ hard-boiled view was boldly stated at the hearings of a Senate Committee which took its turn at investigating West Virginia coal in 1921. William H. Coolidge of Boston, who is still chairman of the exceedingly prosperous Island Creek Coal Company operating in Logan County, said: “We keep out the organizers of the United Mine Workers for exactly the same reason that those whose pictures are in the Rogues’ Gallery are kept out of lower New York.” And yet, in 1920, the U.M.W.A. could claim in its membership more than half of the 103,000 mine workers of West Virginia. The Logan County battle had not yet been lost. The betrayals of 1922 which began the destruction of the union in the Kanawha and Fairmont fields were still in the future.

Today, West Virginia challenges the National Miners’ Union as an unorganized state, leading the country in coal production, in coal deaths, and in low wages.

Who are the operators who have been building up the coal production in West Virgina?

What interests do they represent?

Formerly West Virginia operators complained that the northern operators were in a conspiracy with the union to prevent the development of the southern fields. Now the northern operators have themselves established larger interests in West Virginia, and north and south show a united front against the union.

Everyone has heard about the large West Virginia coal holdings of U.S. Steel and the indirect holdings of the Pennsylvania Railroad through its affiliated Norfolk and Western Railway. And miners have not forgotten how the West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania mines of Rockefeller’s Consolidation Coal were played against one another, with the connivance of John L. Lewis, during the strike of 1922. But that is not the whole story.

R.B. Mellon, director of the Pennsylvania Railroad and dominating owner in the Pittsburgh Coal Company, has been extending his coal interests through other corporations.

In 1924, R.B. Mellon and R.K. Mellon organized the Koppers Company of Delaware as a holding company, a polite term for a corporation which controls other corporations and skims the cream of their profits. The Koppers subsidiaries include several by-products coke companies, construction companies, etc., and several coal companies of which the following are clearly operating in West Virginia: Elkhorn Piney Coal Mining Co., Houston Coal Co., Thacker Coal and Coke Co., and Tidewater Coal and Coke Co. (Incidentally Youngstown Sheet and Tube participates in the management of Elkhorn Piney Coal and besides that has its own coal interests in West Virginia.)

And just the other day financial papers quoted Secretary Andrew Mellon as stating that his largest coal investments are in the Koppers mines in West Virginia and Kentucky.

A fresh link from the Pittsburgh Coal Company to the southern West Virginia coal fields was set up last May (1928) when the Comago Smokeless Fuel Company was organized to take over and operate properties in McDowell County and to operate properties in Raleigh and Wyoming Counties. The president of this new company, H.N. Eavenson, is a director of Pittsburgh Coal. The Mellons and persons closely associated with them have in recent years set up several other connections in Kentucky and Alabama coal.

Just the other day it was announced that the $200,000,000 merger of West Virginia coal interests had fallen through and the committee had disbanded. Negotiations may well be continuing in private, or in the near future a new committee may be formed to take up the matter again. Meanwhile look at the interests represented on that committee. They are typical of the forces that confront the miners in West Virginia.

The chairman, Isaac T. Mann, is president of Pocahontas Fuel and a director of the Norfolk and Western Railway. Other directors of Pocahontas Fuel represent New England steamship interests. In 1917 that company’s dividends, which had been running at about 6 per cent a year, shot up to 32 per cent. In 1919 they were 19 per cent. Since 1919 the dividend rate has discreetly been kept as dark as possible, but the fact of a stock dividend of 300 per cent in 1922 is public knowledge.

R.H. Knode, the president of the General Coal Co. in West Virginia, is also a director and vice-president of the Hazle Brook Coal Co., a Donald Markle Anthracite Company which has just been merged with Markle’s Jeddo-Highland Anthracite Company. The Markle companies are tied up with Morgan. They have among their directors men who are interested also in the notorious Westmoreland Coal Company and in the large but temporarily unsuccessful West Virginia Coal and Coke Co.

T.B. Davis of New York is vice-president of Island Creek Coal Co., the largest of the four closely related West Virginia companies dominated by Boston officials of the U.S. Smelting, Refining and Mining Exploration Co. The smaller companies in the group are Pond Creek Pocahontas, Mallory Coal Co., and Hardy Coal Co. One of the directors, I.J. Freiberger, is–or has been–president of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce. The vigorous anti-union sentiments of the president of Island Creek Coal, William H. Coolidge, we have already noted. Island Creek is also the company which in the course of 12 years has piled up profits of $28,630,758 on stock with par value of $118,801. Its largest profits have been reported since the war. Only last year a 400 per cent stock dividend was handed out. R.H. Gross, president of the New River Company, is another Boston man with holdings in half a dozen independent copper ventures. Other directors represent New England manufacturing and steamship interests.

A third New England group sat in at the committee through William C. Atwater, president of the American Coal Co. of Alleghany County (W. Va.) which operates on land leased from the Norfolk and Western Railway. The Atwater family is deep in New Bedford textile interests. William C. himself is president of a coal selling company which claims a direct interest not only in the American Coal Co. but also in, ten smaller West Virginia companies. Another director of American Coal is J. L. Steinbugler who is a director also of Pittsburgh Terminal Coal Co.

Perhaps most significant was the presence on the committee of R.C. Hill, chairman of Rockefeller’s Consolidation Coal and partner in the firm of Madeira, Hill and Company. He represents more or less directly at least four connections in West Virginia besides the Consolidation mines in the Fairmont field.

First, Consolidation Coal Co. is affiliated with the Elk Horn Coal Corporation, operating chiefly in West Virginia and Kentucky.

Second, Davis Coal and Coke is directly a Rockefeller company. It holds the lease on 31 mines and more than 100,000 acres owned by the Western Maryland Railway. It controls also some 25,000 acres of other West Virginia coal lands.

Third, R.C. Hill’s own company, Madeira Hill, operates through a subsidiary two mines in the Fairmont Field. (Madeira Hill, by the way, directly and through various subsidiaries have large anthracite and bituminous interests in Pennsylvania.)

Fourth, Brookes Fleming, Jr., the West Virginia director of Consolidation Coal, sits on the board of directors of two minor West Virginia companies, the Ohley Coal Co. and the Watson Coal Co. (One step further removed is the Cabin Creek Consolidated Coal, a 4,000,000 ton company, whose directors include W. A. Ohley, president of the Ohley Coal Co. and director with Fleming of the Watson Coal Co.)

Whether the $2,961,000 “investment in allied companies” reported in the last annual balance sheet of Consolidation Coal carries Rockefeller interest into other companies where the connection is not so easily traced, it is impossible to guess.

The secretary of the merger committee, Holly Stover, is currently reported as “Of the National Coal Association.” Incidentally, he wrote some weeks ago to the New York Times defending the conditions at the Stover Coal Company against what he considered an unfair comparison with the mining village (in) the same West Virginia County) owned by Henry Ford. Now it appears that the Stover Coal Company is a direct subsidiary of Inland Steel.

Unfortunately it has not been possible to estimate the tonnage turned out by West Virginia mines connected with northern interests. But it is worth while to list a few of the more important interests besides Mellon and U.S. Steel, which ere apparently not represented on this merger committee. They include the Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation of which Lord Melchett, better known as Sir Alfred Mond, is a director; the Insull-Peabody group in Illinois; New England utility interests; Bethlehem Steel and many of the “independent” steel companies, including the Lake Superior Corporation of Canada; and certain northern railway interests.

Perhaps more immediately important to mine workers is the fact that a large number of northern coal companies besides those already mentioned have now acquired coal properties in West Virginia. To name only a few: Westmoreland Coal, independently of its anthracite connections referred to above; Hi-man Coal and Coke; Keystone Coal and Coke; Youghiogheny and Ohio Coal; Bertha Consumers Co.; the M.A. Hanna Co. of Cleveland; the Cosgrove-Meehan Corporation; and Old Ben Corporation of Illinois. Also the Pittsburgh Terminal besides having a director in common with Atwater’s American Coal Co. has just installed as its new president, H.T. Wilson, president of the notorious Red Jacket Consolidated Coal. Liberal writers are forever stressing the chaos of competitive production and marketing of coal and the advantages in the increase of “captive” mines. (A captive mine is one owned by an industrial or public utility corporation which mines the coal for its own use.) The competitive market does involve genuine difficulties for the miners. It has been the pretext for wage-cutting and union-smashing in once well organized districts. But the growth of “captive” mines has re-enforced the anti-union desires of coal operators with the anti-union drive in other industries.

In spite of the competitive market we have today a united front against organization of coal miners. The three financial giants–Morgan, Mellon, and Rockefeller–are all aggressively hostile to unions. They can guide the labor policy for their own corporations, for related corporations, and for companies operating on lands that their companies own. But this is only one center of their power. Their railroads, which include many of the chief coal carriers of the country, can stall production at any mine by failing to provide cars for the output of coal.

And bankers can threaten to withhold credit if an operator’s policy appears too friendly to labor. The strongest forces in the country are in fact lined up against the miners, who need as never before, the militant National Miners’ Union.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1928/1928-ny/v05-n269-NY-nov-13-1928-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1928/1928-ny/v05-n270-NY-nov-14-1928-DW-LOC.pdf