A look at the capitalist transformation of Turkey in the 1920s under Kemal Ataturk.

‘Kemalism on the Road to Capitalist Development’ from The Communist International. Vol. 4 No. 11. July 30, 1927

THE armies fighting for the independence of Turkey were able to win a brilliant victory over the mercenaries of the Entente imperialists by the self-sacrifice and heroism of the “mehmedtchiks” (peasants of Asia Minor mobilised for the army). Before the end of 1922 Anatolia was entirely cleared of the invading forces which were driven into the sea or captured. The armed people encamped at the gates of Constantinople and the Dardanelles, occupied by British troops, and waited patiently for an opportunity to finish the work of national liberation.

In Lausanne, the Kemalist diplomats showed themselves unable to exploit as they should have done this exceptionally favourable situation, in order to free Turkey once and for all from all imperialist interference. They were very exacting and ambitious in regard to political independence, but they were not insistent enough where economic problems were at stake. Here the roles were reversed. The allied delegates would not cede an inch of the rights previously attained. Convinced that all political privileges are the result of economic pressure, they would not consent to any definite solution implying even the least bit of sacrifice on their part.

The debt question was simply dissociated from the Treaty and adjourned; it has not been settled yet. In regard to the Customs question they imposed on the Kemalists a provisional solution valid until 1928, which subjects them, with a few changes, to the old tariffs. This means that next year–five years after political independence the Turkish Republic will have an entirely independent Customs regime. As to the concessions and big capitalist enterprises in the hands of imperialist. capitalists, the Kemalists simply recognised their legitimacy with the sole proviso that they should submit to the laws of the country. They hoped that owing to the suppression of capitulations–unequal treaties similar to those in China–they would be able to dislodge imperialist capitalists from the strategic positions of a nation’s economic life simply by equality of treatment as between natives and foreigners.

Bourgeois Illusions

This was, of course, an attitude natural to a nationalist bourgeoisie which looks upon itself as having the exclusive right to exploit the natural wealth and labour forces of the country, but which sees at the same time the danger of severing all connection between itself and international capital, foreseeing that it will eventually have to approach the latter for support. The leaders of the young Anatolian bourgeoisie were dazzled by the fact that, contrary to expectations, they had succeeded in making the imperialist powers recognise the complete political independence of the country. It seemed to them that all else would follow of itself. And instead of jeopardising once more what had been already acquired, they preferred to consent to compromising solutions or to the postponement of contentious points on which opinions were diametrically opposed.

After signing the Lausanne treaty, the Kemalist Government was face to face with the same difficulties as the “Unionist” Government after the revolution in 1908, but with the important difference that world capitalism had already entered upon its period of decline and that in a considerable part of the terrestrial globe the proletariat had snatched power from the hands of the bourgeoisie. The task which still remained to be accomplished was formidable. Abdul Hamid had been able to keep in power for 33 years only by satisfying the contending appetites of the rival imperialists by the concessions which he bestowed on them in turns. Thus it happened that all the live sources of national production had become the property of foreign capitalists. A rapid invasion of all the spheres of economic activity by these privileged capitalists had literally stifled the middle classes, and hampered their development by a competition with which they could not cope. To try to limit this systematic pillage of the national wealth, the most conscious sections of these classes, under the leadership of the Committee of Union and Progress, (the “Young Turks”), effected a constitutional revolution and abolished the absolutism of Abdul Hamid.

Influence of Imperialism

But although in power the “Unionist” bourgeoisie was encircled by imperialism and had no support from outside; it could not tear the country out of the hands of the international financiers who had established themselves as if they were in their own country. This inexperienced bourgeoisie (which was by the way very small), was bound to seek the friendship of one of the rival imperialist groups. It soon degenerated and became declassed, playing the role of broker and partner for foreign capital. Nothing short of the exceptional conditions of a state of war could make its government take the initiative in the suppression of capitulations. and give it a chance to develop independently, by letting it enjoy temporarily the power which control over the State apparatus can give.

After Lausanne, the well-to-do sections of the middle classes of Anatolia, represented by the Kemalist party, came into power under more favourable auspices.

Apart from the fact that a breach had already been made in the imperialist encirclement, the path to be traversed had been cleared by the experience of the “Unionists.” But a still more important factor was that five years of unprecedented exploitation of the domestic market, because of isolation from the outside world through the war, had enabled certain sections of the middle classes (peasants, artisans, small industrialists) to make direct contact with national production and to make in the midst of general penury considerable economic progress. Thus the social basis of the new regime was much more robust.

The Kemalists had forces on whom they could depend for the solution of tasks which had discouraged their predecessors. The weakness and corruption of the monarchist epoch had had the disastrous result that all railway lines and ports, all big enterprises engaged in public works, nearly all the mines, the most important industrial enterprises, all foreign trade as well as the principal banks were in the hands of the imperialist capitalists. It was essential to carry on a methodical and patient struggle against this intrusion–if not to remove or paralyse it–at least to place it under thorough control to prevent it impeding the independent development of the nation’s economic life. In this respect one can already ascribe tangible results to the account of the People’s Party.

We will now review in the industrial, commercial and financial spheres the numerous manifestations of this underground economic struggle, which still gives to Turkish nationalism its anti-imperialist imprint.

Transport and Industry

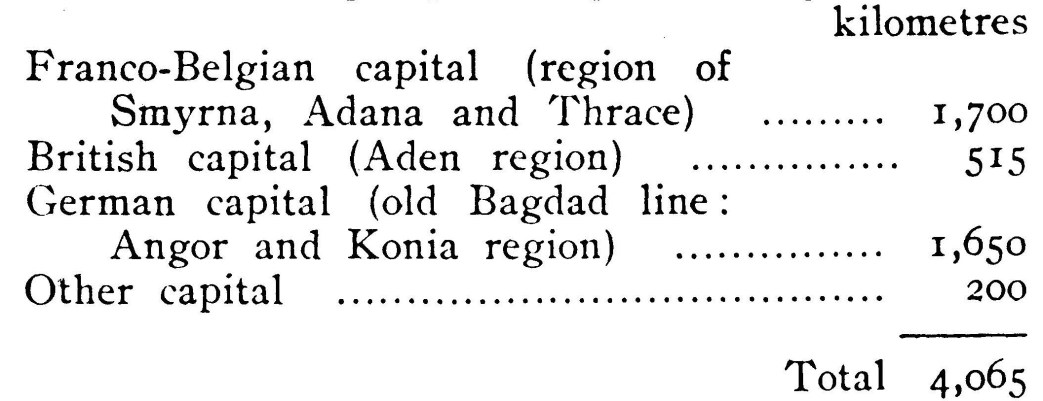

The Kemalists were quick in realising the importance of railways for the proper modern exploitation of the country. They also soon grasped that without dominating the railway lines one cannot aspire to predominant influence on national economy. Therefore they paid from the very start special attention to the question of transport. One can truly say that up till now the pivot of the policy of Ismet Pasha’s Cabinets has been his railway and public works policy. We give below a table illustrating the distribution of the railways of Turkey between the various groups of imperialist capitalists.

During the war the government had taken for military reasons the exploitation of the Anatolian railway line (German capital) into its own hands. One of the chief concerns of the second National Assembly of Angora was to decide the future fate of this railway line. The Assembly was divided into two camps: on the assumption that the State is a bad steward, one side advocated immediate resumption of exploitation by a concessionist company. The other side, on the contrary, basing itself on the encouraging results of State management and on the vital importance of having direct command over this man artery of Anatolian trade, advocated definite nationalisation with compensation. The company did everything to avoid the latter solution. After heated discussions, the advocates of nationalisation won the day. This vote constitutes the point of departure of the railway policy of the Kemalists. Although the government continues to exploit and improve the railway line, it has not yet been able to come to an understanding with the company in regard to the amount of compensation. It is said that the company is to receive 60 to 80 million dollars, the value of all the Turkish railways being estimated at 250 million dollars.

Railways Needed

But it was essential to provide also the other parts of the country with modern means of communication. The network of railways inherited from the old regime only served the Western Southern provinces of Asia Minor. The Northern and Eastern provinces had been utterly neglected. The Nationalist bourgeoisie expected to derive very great profits from these semi-feudal regions. The ambitious projects of the Chester concession were, of course, aimed at connecting Eastern Anatolia. and the Black Sea coast with the centre and the south of the country and introducing modern technique there. After the lamentable failure of this visionary enterprise, no other group of foreign capitalists had offered to execute works of this kind on conditions acceptable to the Nationalist Government.

The unfavourable solution of the question of the Anatolian railway line on the one hand and the various restrictive legislative measures (compulsory use of the Turkish language, dismissal of all the non-Turkish personnel, compulsory registration by the competent authorities, exaction of bail, adhesion to Turkish Chambers of Commerce, etc.), in regard to existing foreign enterprises on the other hand, had prejudiced international financiers against the young Republic. The uncertainty of the situation in connection with the deadlock in the Mosul question and the libelous campaigns against the Turkish Nationalists carried on by the imperialist ranks were a contributing factor to the cautious and far from benevolent attitude of international finance. Not only was no new capital imported, but certain institutions of old standing, particularly those dependent on Great Britain, liquidated their businesses.

Government Building

Determined nevertheless to work for the realisation of its economic programme, the People’s Party decided in 1924 to construct out of its own funds–that is to say by recourse to the State budget–railway lines which it considered essential for the exploitation of the natural wealth of the country. A carefully elaborated plan was launched without delay. Government organs put in hand the construction of the proposed railway lines simultaneously at several points. We give below a table of railway lines in the course of construction or shortly going to be constructed:

If we count the short branch lines in the course of construction, over 600 kms. of railway lines, including many bridges and tunnels, have been constructed by Turkish workmen and engineers with the money of the ratepayers and taxpayers of the country. But this work was making but slow progress. Responsible administrators were guilty of considerable abuses at the expense of workers’ wages and supplies of material. Moreover, these enterprises caused great fiscal difficulties. The Government was intent on accelerating the pace of construction without paying the cost immediately.

Thus, last winter, it accepted with alacrity the offers of two groups of foreign capitalists (Belgian and Swedish) to build the railway lines in question on credit. This is not a concession in the true sense of the word. The railway lines will belong to the State. But the conditions imposed by the capitalist groups are exacting. The real value of the work to be done–over one million kilometres of railway lines and the equipment of the ports of Samsun and Heraclei–is not to exceed 70,000,000 dollars, whereas the treasury of the Republic will have to pay over 100,000,000 dollars in the course of ten years.

The Kemalists are delighted to have to do with non-political capitalists. But the rumour is that city financiers are behind the Swedish group. One may say that these two arrangements are the first step of the Kemalists on the road of compromise with imperialism.

Futile Plans

In the industrial sphere the government has restricted itself to encouraging and supporting private enterprise. As the capital at the disposal of the Anatolian bourgeoisie is very small indeed, words very seldom lead to deeds. We have to do here with a mass of plans which have no future.

At first attention was only paid to the agricultural industry. The latter mostly situated in the regions. invaded by the Greek army had been seriously damaged by the Greek retreat. The government, by ceding these half-ruined enterprises at a ridiculously low price to the protégés of the People’s Party and by giving them loans and subsidies, made it possible for them to reach and even to exceed in the course of three years the pre-war level of production, in respect of distilleries, olive oil and soap factories, mechanised flour mills, the canning industry, etc. Special mention must be made of the leather industry. In regard to these industries not only has there been restoration and amelioration of what already existed, new works with improved technique have also been constructed. These factories produce already enough to satisfy a considerable part of the requirements of the internal market.

Apart from this agricultural industry one can also mention a few electrical works, factories producing building material, a big aeroplane factory (Turco-German), two sugar refineries, etc. The capital invested during the last few years in these industrial enterprises is about 12 million dollars. One may say that one-third of these funds come from the State, one-half from private capital (native and foreign) the remainder, that is to say, about two million dollars, from national savings for it has become the rule lately to give to big industrial as well as commercial enterprises the form of limited liability companies. The mass of small investors who were suspicious of these are beginning to get used to investing their small savings in bonds.

Certain enterprises owe their existence to the participation of these social strata.

Apart from the protective measures contained in the Encouragement to Industry Act, the government gives industry financial support in various forms amounting to about 400,000 dollars annually. Enterprises financed by foreign capital, provided they parade under the label of a Turkish company, benefit by all the exemptions laid down by this Act.

As to heavy industry, with the exception of the State munition and gun factories and a few big railway repairing workshops, it is non-existent in Turkey. There is certainly a small metal industry which gives employment to 15,000 workers. But there are very few enterprises employing more than 100 workers. In most cases, the workshops employ 10 to 50 workers or even less.

Of late there has been much discussion as to whether Turkey can be converted into an industrial country. The absence of iron mines made people generally inclined to consider impossible the establishment of heavy industry, which is the primary condition of industrialisation. The discovery of abundant iron deposits in the Kemlik and Torba regions has made the young bourgeoisie very hopeful. Immediately an ambitious plan was made for the extraction of iron ore and for industrialisation. The government was to take from the budget eight million dollars for the exploitation of the iron mines, to lay the foundation of the heavy industry. As yet nothing has been done in this direction.

With a few exceptions the other Turkish mines are exploited by foreign capital. In this sphere, too, lack of but insignificant beginnings. In this sphere, too, lack of capital is inducing the Kemalists, who are determined to work in the direction of capitalist development, to arrive at a compromise with imperialism.

Commercial Development

The efforts of the Kemalists to develop the country and to increase national production have also given a great impetus to commercial transactions and particularly to foreign trade. This relative development is due to the improvement of the social conditions of the well-to-do sections of the national peasantry and bourgeoisie, whose representatives, the People’s Party, encourage them in every possible way to enrich themselves through the social changes imposed by the new legislation, through the gradual introduction of modern commodities into the villages of Anatolia, where prior to the revolution the population led a very primitive existence, and finally, through the ever-growing participation of the Turkish population in all the spheres of economic activity.

Contrary to the general assumption, most of the foreign trade is still in the hands of foreign firms, Greek and Armenian exporters who continue to carry on their business through the intermediary of Turks whom they use as figureheads. But one should bear in mind that in the course of the last three years the essentially agricultural and industrial young bourgeoisie has succeeded in gaining ground in the commercial sphere. It is precisely the commercial and financial section of the Kemalists which inclines more and more towards a prompt compromise with foreign capital. The daily paper Djumhouriet République” is the mouthpiece of this section of the Nationalist bourgeoisie.

The official figures for foreign trade lead to the following conclusions:

In 1923 a simultaneous decrease of imports and exports was noticeable as compared with 1922. This was due to the devastation in the Smyrna and Afion region by the Greeks and by the Allied armies of occupation on their departure. In 1922 Turkish trade was still entirely dominated by imperialist capital.

Since 1923 the trade balance has been steadily developing. Imports and exports have increased simultaneously, the later at a more rapid rate than the former, It is worthy of note that the trade balance of Turkey always shows a deficit. This is not due to any of the economic and social changes which have taken place in the country. Under the old regime there was also an unfavourable balance every year. A study of the official Custom House bulletin from 1887 to 1911 will show that there is an average yearly deficit of five million pounds gold. Imports

(Total Turkish gold pounds)

From 1887 to 1911: 642,500,000, Exports: 406,100,000

This means a deficit of 238,000,000 Turkish gold pounds in 25 years. This continuous flow attracted the attention of economists, who failed to find any justification for it in the economic conditions of the country and in the general trend of business, all the more so as the figures given by the statistical departments of the country interested in the foreign trade of Turkey did not correspond with those given in the official bulletins of the Turkish Customs. According to a statement by the Angora Commissariat for Trade, published in a Constantinople newspaper, the explanation of this anomaly was that goods exported across the Southern frontiers of Asia Minor in most cases escaped registration, and on the other hand exporters had the habit of declaring figures generally 20 per cent. or thereabouts lower than the actual figures.

It is interesting to note that for the last few years this unfavourable balance has tended to decrease gradually. It fell from 60.1 million pounds in 1923 to 34.9 million in 1924, only to increase again to 43.1 million in 1925. It is estimated that it will not exceed 30 million for 1926.

The distinctive feature of the present commercial development of Turkey–whether in reference to limited companies or in respect to private enterprises–big enterprises predominate and small enterprises disintegrate, just as in rural economy. Unfortunately, there are as yet no statistics giving figures of this process of absorption of small trade by the big sharks. According to superficial information gathered in the regions of Constantinople and Smyrna, £30,000,000 of trading capital belonging to small traders has been withdrawn from the market. Allowing on an average 500 Turkish pounds per shopkeeper, one arrives at a total of 60,000 traders ruined and retired from business.

Trade Monopolies

Under the old regime of capitulations, Turkey could not establish a monopoly and raise Customs dues. There were only a few monopolies (salt, fisheries, tobacco), administered by the Public Debt. In regard to Customs, the Kemalists were bound by the Treaty of Lausanne, to abide by the existing tariffs, reserving to themselves the right to multiply them with certain coefficients fixed in the treaty, to compensate for the depreciation of money, but in regard to the question of monopolies the Turkish government was given complete freedom of action.

Since 1925 the government has made full use of this freedom; first of all by abolishing a clause of the contract which granted exploitation of the tobacco monopoly to a group of Franco-Belgian financiers (Régie Générale des travaux publics et des chemins de fer). The government reimbursed the capital invested by this group. The experiment of directing the tobacco industry and trade through an apparatus under the direct control of the Finance Ministry has produced excellent results. The receipts, which under the co-interested régime had never exceeded five million Turkish pounds per year, reached 10 million Turkish pounds in 1925.

Moreover the government introduced a whole series. of new trade monopolies of various kinds. Some provide for the exaction of a supplementary Customs tax in the guise of monopoly of foreign trade; this is the case in regard to oil and sugar. Purchase and sale of these commodities within the country are perfectly free, only that all importers are obliged to inform the administration of the corresponding monopoly when placing their orders and must procure a license varying between five and eight piastres (1d. to 2d.) per kilogram. The administration on its part can if it so wishes import a stock of merchandise on its own account and can dispose of it to the retail traders at cost price plus the monopoly tax. Thus it is supposed to play the role of regulator.

Monopolies Farmed Out

There are others which are monopolies pure and simple, comprising imports, manufactures and sales. Such are the monopolies of spirits, firearms, explosives, matches, cigarette paper, etc. As the government has not enough capital to invest in these enterprises, it has preferred to give up its right to exploit them to groups of foreign capitalists. Thus a group of Polish capitalists have taken over the monopoly of spirits, a group of French capitalists the monopoly of explosives, and a group of Turko-Israelite capitalists, the match monopoly. The most characteristic conditions imposed on these exploitation companies are: payment in advance of a considerable sum representing the revenue anticipated for a certain number of years: establishment in the country of a minimum of industrial enterprises whose business it is to satisfy the requirements of the internal market participation in the administration of the companies of Turks enjoying the confidence of the Kemalist Party. Thus for instance, the chairman of the Board of Directors of the spirit monopoly is the former Minister of Finance, Hassan Bey.

As to the mass of the population the consequence of these monopolies is: higher prices for the commodities. in question, accompanied by very reduced consumption. We have already shown in this article by statistics that this reduction has assumed proportions in regard to oil and sugar which have alarmed administration of the Indirect Taxes Department. During the first seven months of 1926, compared with the first seven months of 1925, sugar consumption decreased 26 per cent. and the consumption of oil 34 per cent.

One should also bear in mind that these monopolies are very hard on small traders who cannot sell their merchandise at a profit, and being burdened with fiscal charges beyond their means are compelled to close their shops.

The attitude of the Kemalists to the workers is dictated by the constructive principles of their economic policy as a whole. Our analysis has fully proved that the Nationalist bourgeoisie and the People’s Party, working hand in hand, are developing the utmost energy, are taking advantage of all opportunities, are making full use of the resources and the power of the State and are mobilising the whole nation for the sole purpose of concentrating in their own hands all the available capital of the country and of accumulating new capital as rapidly as possible.

Increased Exploitation

They enforce this concentration by the use of the most brutal methods of pressure and threats and by bringing into play the economic laws of unhealthy competition by means of administrative and fiscal measures. The rapid disintegration of small exploitation in town and country which results from this is steadily swelling the ranks of the proletariat. Although the demand for labour power increases with the progressive development of production, the more rapid bankruptcy of the petty bourgeoisie and the poor peasantry precludes the absorption of all the labour power on the market. Thus we have now in Turkey a reserve army of unemployed which will help the bourgeoisie in its development by providing it with cheap labour.

This is a very vital question for the young Turkish bourgeoisie. It cannot accumulate capital except by relentless exploitation of labour power and of the mass of consumers. It needs a disorganised proletariat unable to offer any resistance to its enslavement in the interests of the capitalists. Moreover, the Nationalist bourgeoisie has to exact from the workers excess surplus value, as it has to cede a considerable part of it to foreign capitalists on whose support it depends.

Attacks on Workers

These being the aspirations of the Kemalists, they have been relentless in their oppression of the working class since they have come into power. This oppression has taken various forms according to circumstances, but its object always remained the same. When they endeavour to place their own creatures at the head of trade unions, when they suppress labour papers, condemn Communists, foment rivalry among workers of different nationalities or support in exceptional cases certain of their demands–their sole object is to disorganise them, to deprive them of conscientious leaders, to damp their fighting spirit, in a word to sow among them disorder and pessimism in order to kill in them the spirit of solidarity and class consciousness.

The C.P. of Turkey is doing its best to counteract this demoralising policy. Turkish workers have already a long time ago realised that their salvation lies in an indefatigable struggle against the exploiting classes and that they have no other friends and defenders but the Communists. Revolutionary propaganda has a great influence over them and all the vexatious and repressive measures of the Kemalist authorities add only to their hatred for the bourgeoisie, be it Kemalist or Unionist.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-4/v04-n11-jul-30-1927-CI-grn-riaz.pdf