An overview of the labor movement in Canada when still a Dominion, stuck between England and the United States, by Scottish-born Jack MacDonald, then chair of the Communist Party of Canada.

‘Trades Unionism in Canada’ by Jack MacDonald from Labor Herald. Vol. 1 No. 5. July, 1922.

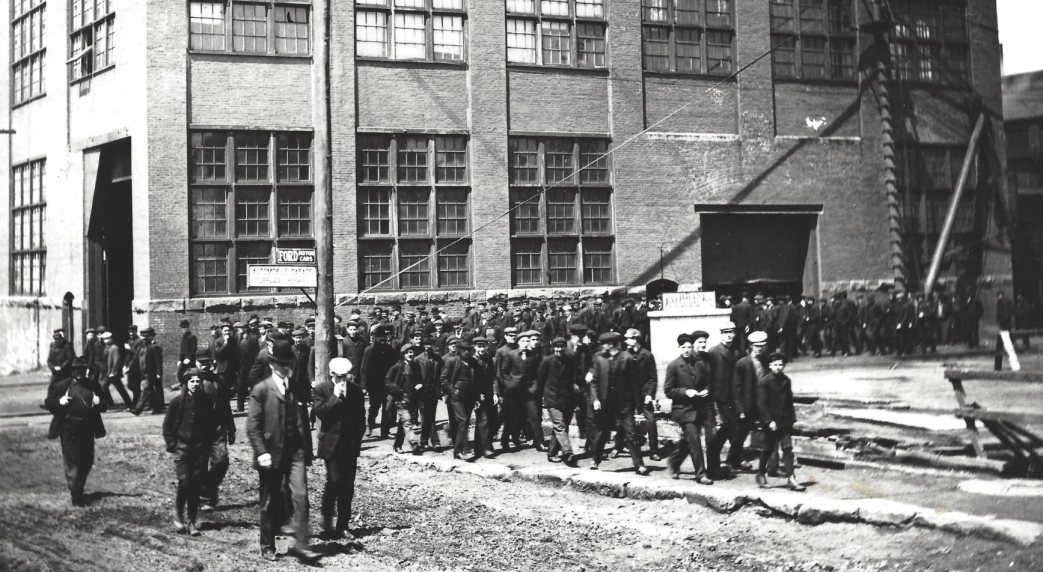

THE trade union movement in Canada has developed under the social and economic conditions created by its peculiar position. Canada is dominated by two great powers–England and the United States. Politically a part of the British Empire, Canada is becoming more and more dependent in finance and industry upon Wall Street. Downing Street and Wall Street being at times in conflict, Ottawa (capital of Canada) is bent and torn between them. Moreover, the farming interest is raising its voice, and having some peculiar interest at odds with both Downing Street and Wall Street, complicates still further the situation. Capitalist Canada is not a unit; it is a house divided against itself. And the labor movement is just beginning to make itself heard.

Canadian Labor also is greatly influenced by two great labor powers, the British Unions and the United States Unions. Partaking of the philosophy and traditions of the British, yet it is organically hooked up with the United States unions because of the close economic connection between the two countries. The great bulk of Organized Labor in Canada is part and parcel of the International Unions with headquarters in the United States–yet the Canadian, like the British rather than like the U.S. movement, stands for the Labor Party in politics and is affiliated to the Amsterdam International.

Thus the Canadian Labor movement stands somewhere between the British and United States movements. It finds it impossible to progress as far as the British, but neither can it remain as backward as the U.S. It stands somewhere in between, but, while the British influence of ideas and programs is strong, undoubtedly the U.S. influence of economic relationship is the most vital and important.

Independent and National Unions

According to available statistics there are approximately 300,000 trade unionists in Canada. The vast majority of these are members of the “Internationals,” of the great unions with headquarters in the United States, mainly of the American Federation of Labor. In addition to the Internationals, there are also a few independent unions, or federations, which are nationalist in character. Those in the railroad industry are described in another article. Some of the other most important ones are as follows:

The Canadian Federation of Labor is a federation of purely Canadian unions. Its title is more pretentious than its strength warrants, as very few unions are affiliated, and these are weak. The pioneers of this movement were the Pressmen who seceded from the International Typographical Union nearly 15 years ago, at the time of the struggle for the eight-hour day. A Toronto local of Electrical Workers, formerly of the International, now the Electrical Workers of Canada, is the strongest unit in the Federation. This local seceded from the International about two years ago. Toronto, Ontario, is the center of the Federation. Small units come and go, and its total strength is never more than a few thousands. A short time ago an official publication was launched, Canadian Federationist, which, according to late reports, is in bad financial straits. Generally speaking, the secession unions which make up this federation are imbued with a narrow nationalist spirit, and have a deep prejudice against being governed “from the other side.”

The National Catholic Unions are of recent origin, and are located solely in the French-Canadian Province of Quebec. Born and reared under the direct control of the Catholic Church, they are an attempt, (1) to prevent the organization of the Quebec workers in the same unions with fellow workers in the other provinces, and (2) an attempt to bring the question of religions into the economic organizations of the workers. They are confined solely to members of the Catholic faith. Their strength has been gradually increasing, and is now around 35,000. There is a strong sentiment among the employers in Quebec against the International Unions. Quite recently the Premier made a bitter attack upon them, he was infuriated at the strong stand taken by the Typographical Union. The question was raised in the legislature, and the threat was made of outlawing the International Unions in Quebec. But even the Catholic unions, it is interesting to note, have whetted the appetite of the workers for organization, and bid fair to thwart the purpose of their organizers. The meager concessions given them, as a formal recognition of their organized state, have also given an inkling of what a real organization could and would do. The Lumber Workers Industrial Union of Canada, formerly the British Columbia Loggers, were at one time a strong organization. The present conditions are, however, very adverse, with the closing down of many of the lumber camps due to the depression. The lumber workers became affiliated to the One Big Union at its inception, and were its greatest financial support. In 1920, however, they broke away because of disagreement over the form of organization, and took their present name. In spite of the hard times they are now going through, this virile and radical organization has blazed the trail for the Canadian labor movement by deciding in Convention, some months ago, for affiliation to the Red Trade Union International. They have no rivals in the Canadian lumber woods, and a revival in the industry will give these stalwarts the opportunity of making their power felt in Canada once again.

The One Big Union dates from the conference held in March, 1919, at Calgary, Alberta. About 230 delegates from Trades Councils and local unions of the Internationals, of the four Western Provinces–British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba–met and made some momentous decisions.

The Western delegation at the Annual Dominion Trades and Labor Congress had always comprised the radical or left-wing. Apparently becoming impatient at the slow progress of their ideas amongst the Eastern workers, and without foreseeing the disastrous effect that their decision was to have on the movement in general, this conference decided to ask the membership to sever all connections with the International organizations.

The One Big Union has changed greatly in its short life. Today its most intense propaganda is against industrial unionism. The Bulletin of May 11th carried a long editorial, since reprinted as a pamphlet, the burden of which is that “the advocacy of one union for one industry is a reactionary step.” It may therefore be of interest to know what was the attitude of the Calgary Conference, which launched the One Big Union. Resolution No. 2, which was carried unanimously, reads as follows:

“Whereas, great and far-reaching changes have taken place during the last year in the realms of industry; and

“Whereas, we have discovered through painful experiences the utter futility of separate action on the part of the workers organized merely along craft lines, such action tending to strengthen the relative position of the master-class; therefore be it

“Resolved, that this Western Labor Conference place itself on record as favoring the reorganization of the workers along industrial lines, so that by virtue of their industrial strength the workers may be better prepared to enforce any demand they consider essential to their maintenance and well-being.”

Resolution No. 3, carried, read as follows:

“Resolved, that this Convention recommends to its affiliated membership the severance of their affiliation with the International organizations, and that steps be taken to form an industrial organization of all workers.” Section 5 of the policy committee report is also interesting:

“In the opinion of the committee it will be necessary to establish an industrial form of organization.”

In May of that year came the memorable Winnipeg general strike. While this was one of the most magnificent displays of working-class solidarity in North America, culminating in the imprisonment of the strike leaders, it also gave stimulus to the formation of the O.B.U. which came in June. The movement, under the slogan of industrial unionism and secession from the Internationals, virtually swept the Western Provinces. Official figures placed the membership at around 40,000. However, it failed utterly in its effort to invade the East. When we recall that the Eastern Provinces are the industrial and manufacturing provinces, containing the bulk of the population of Canada, it is clear that this fact doomed the O.B.U. Since then there has been progressive decay in that organization. Reports of membership are conflicting, but certain it is that it does not exceed 4,000 and in Winnipeg alone does it have any strength. There is not a trace of it left in Vancouver, while in Regina, Edmonton, Calgary and Saskatoon, all former strongholds, nothing but the name remains. Today, when the O.B.U. is denouncing Industrial Unionism and the Red Trade Union International, we find most of its former spokesmen are now against the policy of dual unionism, and are for industrial unionism through amalgamation, and the program of the Red International; among these may be mentioned Kavanagh of Vancouver, Mogridge and Lakeman of Edmonton, Mills of Saskatoon, and Fay of Calgary. The best elements are thus departed from this old mistake, and are now hard at work in both East and West (which are now closer together than ever before), endeavoring to consolidate the labor movement as a whole. All now realize that the first prerequisite for even defensive struggle is a unification and consolidation of the existing organizations.

The Real Labor Movement of Canada

The vast majority of organized workers in Canada belong to the internationals. The group of first importance, as they constitute the keystone in the labor movement of the country, is undoubtedly the railroad unions. The building trades, metal trades, and miners, follow in order of importance. The Canadian District Council of Metal Trades Department, A.F. of L., covers the metal trades outside the railways; the railroad shopmen constitute District No. 4 of the Railway Department. The United Mine Workers have a membership of approximately 20,000, organized in two districts, viz; No. 18, in Alberta, in the West, and No. 26 in Nova Scotia, the East.

Canada is a land of vast distances, which militate against frequent conventions in the trade union movement. The chief work must, of course be done in the large cities. From Halifax to Vancouver is a far throw, but the work must be carried on, on that scale. This is the reason that the militant union men and women of Canada have been inspired by the work undertaken by the Trade Union Educational League, which is working in the unions from coast to coast, getting a common program into action in every town and city throughout the Dominion.

As a whole, the Canadian movement presents even better opportunity for our work, for immediate results, than any other section. The movement is more advanced in its social and political outlook than the movement across the line. The Dominion Trades and Labor Congress, the counterpart of the A.F. of L. Convention, not only has gone on record for independent political action, but has taken the initiative in the formation of Provincial labor parties, to which trades unions and other working class organizations can affiliate. At the last Congress the basis was laid for the linking up of these Provincial parties into a Dominion-wide Labor Party.

The backwardness of the American labor movement has been used as an argument by the advocates of Canadian national unionism; they have cited the lack of national autonomy, the absence of power to bring strong pressure on the Dominion Government, as their strong argument against the Internationals. However true it may be that the Canadian unions lack power, it is certain that such power cannot be achieved through the policy of splitting up the movement as has been done with the nationalist unions and the O.B.U. And just as the confusion of dual unions is insupportable, so also is the multiplication of craft divisions that now exist. The only solid basis of working class power industrial as well as political, lies in the movement for consolidation and amalgamation. The present Councils of autonomous unions, separate headquarters, separate constitutions, separate sanctions to procure for each projected action–all this is obsolete and must be scrapped. From a purely financial point of view it is untenable. Millions of dollars annually are literally thrown away upon duplication of offices, editors, organizers, and officials. Because of our lack of unity, among the workers organized, we stand helpless before the solid phalanx of the master class.

The trade union movement in Canada, as in other countries, is passing through its most critical period. The employers are attacking viciously. The movement is relatively weak. Thousands upon thousands of the workers know our weakness, and know that industrial unionism is the answer. Nowhere is this message given to the rank and file, but what is received with acclamation. Why then do we not make more progress? The reason is our lack of organization among the militant unionists in the past. We have relied upon a blast of trumpets. That will not do the deed. Steady, hard, plodding work alone will suffice, and thorough organization. Instead of being content with damning the reactionary machine, we must build our own machine–not for the gratification of personal ambitions, but for furthering militant unionism. The Trade Union Educational League has been formed for this purpose, and is already taking up the task. Let us all take hold, and with this instrument ready to our hands, set to remolding the trade union movement along industrial lines, infusing it with a new spirit, and thus make it fit to cope with the ruthless attacks of the capitalist class.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v1n05-jul-1922.pdf