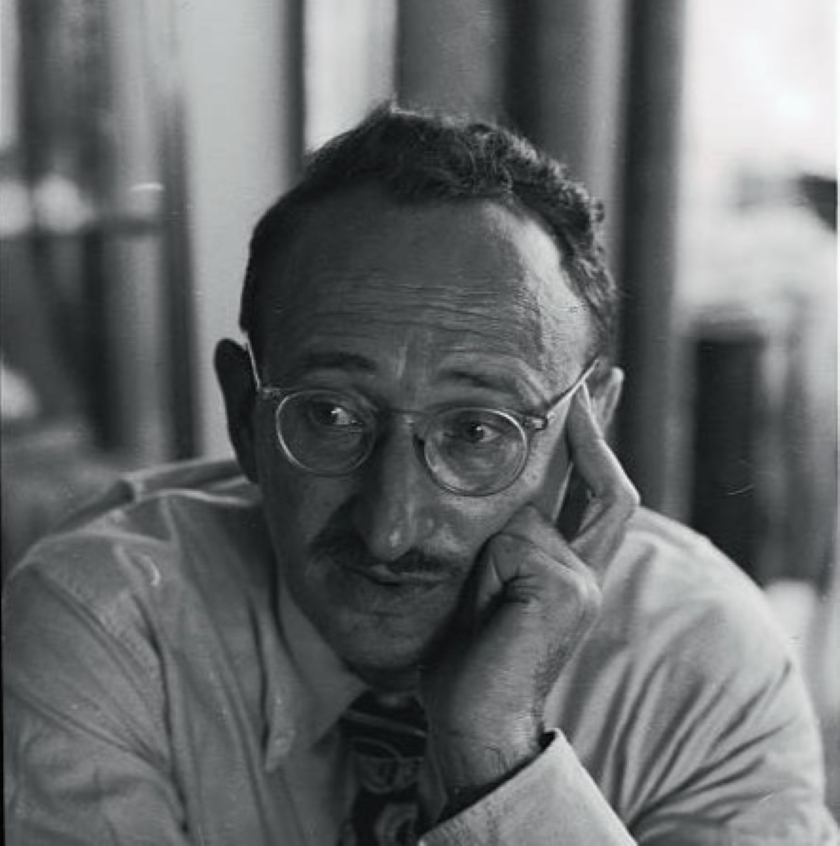

A famous essay from Sidney Hook.

‘The Meaning of Marxism’ by Sidney Hook from Modern Quarterly. Vol. 5 No. 4. Winter, 1930-31.

SINCE its very inception the doctrines of Marx have been in a crisis. First it was the academic German professors of economics who protested against its lack of scientific objectivity, condemning it because it was not wertfrei. Later came the revisionists and syndicalists, who from different points of view attacked its soulless mechanism and economic fatalism. After them came the revolutionary Marxists who accused the self-styled orthodox of concealing Marx’s revolutionary motivation behind Marxian dogmas. Today revolutionary revisionists are urging that Marx be brought up to date with the newer findings of physics, biology and psychology. It is clear that a system of thought which has lived through so many crises must be very much alive indeed. Each age has brought a new refutation and a new defence until in the welter of denial and counter-denial the meaning of Marxism has become vague and obscure. In some quarters it has become an epithet of abuse; in others, an honorific term for militant class-consciousness. In Russia, it is a symbol of revolutionary theology; in Germany, of a vague social religion; in France, of social reform, and in England and America, of wrong-headed political tactics. The trouble has been that both friend and foe have been more anxious to discover whether Marxism is true or false than what Marxism, as a system of thought contained in the writings of Karl Marx, actually means. It is Marx’s meaning that must first be discovered before we ask whether his teachings are true or false.

The clues to a man’s thought, whenever texts and interpretations are ambiguous, lie in his logical purpose (not personal motive) and in the specific social context in which his doctrine arises. Whether the truth of those doctrines is historically conditioned is another matter which we need not discuss here. In one sense it is, and in another it isn’t. But the meaning of the doctrines can only be grasped when we understand the purposes they serve, what it is they oppose and the logical consequences which follow from their assertion. As yet no critical study of Marx has been made from this point of view. No one has applied the method of historical materialism to Marx’s own doctrine itself. No one has critically evaluated the relative weight of the available texts, traced the development of Marx’s thought, examined the apparent contradictions in his writings in the light of the contrary doctrines of his different opponents, and sought to discover in this way the spirit and rationale of the system. The critics of Marx have generally been inspired to write their books in order to save their country from the “red terror”; and the defenders of Marx in order to hasten the revolution. Both have sought for what they needed and found what they sought. In their eagerness to score on one another, they have not even always taken the trouble to understand Marx’s language. I shall cite one instance of this before I go on to state my general theses. The furious discussion as to whether Marxism is a science or not has been based on the assumption that the word Wissenschaft in Marx always implies natural science and the method of natural science. This is a rank error. Where Marx uses the term Wissenschaft to characterize his own standpoint, he means what all the Young Hegelians meant by the use of that term, criticism based upon the standpoint of development. The difference in the two meanings is enormous.

The following theses state dogmatically the general conclusions of detailed research extending over many years. They will before long be developed at length in book form.

1. Marxism is primarily a method. Its specific conclusions may turn out to be wrong, but unless the method used to impeach its results is different from its own, the abandonment of those particular results does not prove the inadequacy of the method. To correct Darwin’s views on sexual selection by using Darwin’s method is not to refute Darwinism. To refute Marx’s specific views as to when and how a revolution will take place is not necessarily to invalidate his method. Orthodox Marxists as well as anti-Marxists, by refusing to distinguish between the essential method and tentative results of Marxism have revealed a common ignorance as to what scientific method means.

2. Marxism is a method of social science or sociology. Marx was the first to maintain the autonomy of social laws, holding that they were not reducible to laws of physics or biology. Consequently, determinism for Marx means social determinism not natural determinism. “It is not man’s consciousness which determines his existence, but man’s social existence which determines his consciousness” (my italics). The consequence of this distinction between natural and social causation is that-

2a. Marxism is decidedly not an historical fatalism. Were social laws to operate with the absolute necessity and irrevocability of natural laws, history would be fated and human effort unnecessary. But social laws differ from natural laws in at least two important respects: (1) they are historically conditioned, and (2) they are laws of human activity. Marxism states propositions about human activity (its desires, ideals, etc.) as it is affected by an historically conditioned social environment. Human effort is the mode by which the socially determined comes to pass. Those who accuse Marx of being a fatalist brazenly ignore the fact that fatalism was a doctrine which Marx vigorously opposed all his life. The belief that social laws operated with the necessity of natural laws was held by the liberal laissez-faire bourgeoisie who drew the consistent conclusion from it that that government was best which governed least and did not interfere with the inevitable play of economic forces. But Marx insisted that “men make their own histories.” Not in any old fashion, to be sure, but within the conditioning limits of the physical, social and cultural environment. Sombart’s “zwei Seelen” theory of Marxism which alleges a conflict between Marxism as an impersonal doctrine of social necessity and Marxism as a passionate movement for social freedom, overlooks the fact that genuine freedom is impossible without a knowledge of what is socially determined. If everything were indeterminate, there could be no freedom.

3. Marxism is a method of social-behaviorism. It is not interested in the personal motive behind individual activity. It holds that the effects of human activities are resultants of the interaction of these motives with themselves and an objective environment, and that the resultant activity can be correlated with and explained by the movement of certain social factors in the environment. In other words, its concept of social causation is statistical. Social events of importance do not take place because this or that individual has this or that ideal, but because the movement of environmental forces continually limits the range and efficacy of those ideals and operates as a selective agency until only those ideals or alternatives remain which correspond to the genuine objective possibilities of the situation. Voluntary human activity is presupposed throughout. Yet it is the behavior and ideology of groups and classes alone which above all interest the Marxist. He seeks to understand them not in terms of the personal motivation of its individual components–which have an enormous range but in terms of social processes that have a definite direction not deducible from conscious human activity. Recognition of what this direction is enables a class to set an intelligent definite goal. The goal implies a Stellungsnahme or vital option which is realized only because. human effort is informed by the knowledge of the condition, limits and powers of man’s activity in the world about him.

3a. Psychology and Marxism. Class consciousness as Marx used the term does not imply individual consciousness of personal interest or mass consciousness of community ties, but an awareness of the historical meaning and mission of the working class in the socio-economic process. “Mission” is not to be understood in a religious sense but in the sense in which we say that a man’s mission is to accomplish a certain task, say, the unification of a country. The mission of the working class, according to Marx, is to bring about the social revolution. Assuming a definite direction and rate in the productive relations of the social order and the relative constancy of certain human behavior patterns, Marx predicted that the social revolution would take place. Not inevitably, of course, but on the condition that human desires, intelligence and will operate more or less as they have in the past. Certain psychological assumptions are here made which seem too simple to modern psychologists, who feel that Marx’s purpose, the social revolution, is a problem to be solved by practical psychology and propaganda alone.

According to Marxism, it is quite true that the effectiveness of propaganda, its method and appeal, depends upon knowledge of practical psychology. But this knowledge is a necessary but not a sufficient condition, for the advisability of carrying on certain kinds of propaganda, the theoretical content and justification of that propaganda, depend upon a prior analysis of the socio-economic environment. All propaganda appeals to the same insight into the way human beings behave, but whether or not one should agitate, at a given time, say, for the organization of rival unions to the A.F. of L. cannot be determined on psychological grounds alone. In other words, psychology can only tell us how to agitate effectively, not what to agitate for. The conditions and limits of psychology are to be found in man’s wider social environment.

4. Civilization, for Marx, is a complex of institutions, traditions, activities, ideologies, etc., such that the understanding of any specific part involves knowledge of other parts (not all) of the culture complex. Just as a history of prices is not a history of economic organization, so an adequate history of religion (or what not) must be more than a history of religious ideas. Doctrines are part of social patterns.

4a. Although reciprocal influences are exerted by the various parts of a cultural whole, the clue to the cultural pattern is given by the social relations of production, which condition in divers ways and in varying degrees determines the rise, growth and decline (not the truth) of other forms of human relationships.

5. Consequently, the method of Marxism is one of criticism. Not only does it draw the consequences of a social doctrine or measure to get its meaning, but it traces its roots to a certain attitude towards the existing mode of social organization, correlates it with basic economic tendencies and class divisions, and reveals its interrelation on all levels with apparently neutral theoretical positions. In other words, Marxism attempts to lay bare those social and historical presuppositions, including the system of values, which are at the basis of cultural divisions. It denies that a presuppositionless standpoint is possible and frankly admits its own pre-supposition in favor of the proletariat. As soon as a relevant cultural issue has been raised, it critically reveals the social presuppositions of the conflicting viewpoints involved. The significance of the fact that every important work of Marx is entitled a critique (the subtitle of Capital is a “Critique of Political Economy”) has never been properly grasped by the critics of Marx.

6. This criticism applied to the fundamental concepts of economics shows that social life is not an organization of things, but of human relations in an historical process. This process seems to substantialize these human relationships into fixed structures independent of time and human purposes. Insight into the fact that the characters of economic exchange are social rather than natural helps to destroy the “personification of things” and the “thingification of persons” in contemporary society.

7. The concrete application of the method of Marx is what is generally known as the theory of historical materialism. This is not an attempt to explain the genesis of ideas, but rather their acceptance and persistence in relation to the conditioning social environment. The genesis of ideas in the individual mind is a subject for investigation on the part of the psychologist. To explain, however, the acceptance and survival of this idea rather than of another is the task of the sociologist. The actual degree to which this connection between ideas and class interests exists is an empirical matter. The more organic a culture is, the closer will the correlations be; the more dynamic it is, the more difficult will it be to establish those correlations.

7a. Marx’s logical method as applied to social events must of necessity be the logic of the process. The Dialectic method is the only method which can unravel the structural interrelations of a whole in movement. The subsidiary categories employed are “relative totality” which distinguishes Marx’s thought from the atomism of traditional empiricism, and “human need or purpose,” which marks the break with absolute idealism. From this follows the rejection of the correspondence theory of truth and the emphasis upon practical activity as a test of validity.

8. Marxism teaches the indissoluble unity of theory and practice. A social theory is not merely an abstract interpretation of processes existing independently of man, but an assertion of a point of view from which those processes are to be transformed. It maintains that social practice is really the expression of social theories, even when the latter are not avowed. Knowledge of how selective bias enters into the determination of allegedly eternal truths in social affairs is a challenge to those truths and the affairs they express. One bias is superior to another in so far as the natural objective possibilities of the situation make the practices which follow from it consistent and adequate. The meaning and test of any theory ultimately lies in its consequences for action (not necessarily of a narrowly practical sort); its rules are prescriptions and its propositions implicit directions to introduce changes in the social environment.

8a. The opposition customarily drawn between theory and facts naively assumes that facts (as distinct from things) exist in rerum natura and that theories must adjust themselves to something completely antecedent. Every scientist knows that the meaning of the so-called crucial fact often depends upon the theories it is supposed to test. This is not only true in the natural sciences, as anyone, for example, who has examined the geneticist’s evidence for the inheritance of acquired character knows, but even more so in the social sciences which have a valuational basis and study social change in order to control it. This brings us to the question of-

9. The Ethics of Marxism. Marx’s refusal to urge social reform in the name of abstract principles of justice has led to the belief that Marxism is a mechanical theory of social causation which has no place, save at the cost of a contradiction, for human activity in behalf of ethical values. This is a mistake. Marx opposed all natural rights doctrines and authoritarian morality of the Kantian stripe on the ground that their ethical claims had no relevance to social tendencies at work in the world. Marx’s ethics, as well as his theory of history, were naturalistic. Marx’s ethics is expressed in what he wanted; his theory of history in what he knew. But we have seen that what he wanted was informed by what he knew. Marx shared Hegel’s insight that will, feeling and intelligence reciprocally conditioned one another, and that knowledge makes a difference by showing not only what it is that we really want, but by indicating what the probabilities are of our getting it. Marx did not denounce the Utopian socialists for having an ethics–for being socialists–but for having a Utopian ethics, for being, like so many revolutionary revisionists today, muddle-headed socialists. He criticized them for a romanticism which paraded in the guise of a common-sense rationalism, for a scientific reformism which believed that it could legislate into existence the very alternatives between which it made its choice, instead of recognizing that these alternatives were given by the socio-economic world in whose making their own generation had no hand. What remains to be done by Marxists today is to explicitly formulate a theory or scale of goods in terms of the possibility and desirability of certain kinds of consumption values (including the cultural, of course,), to develop the social psychology assumed by their method and to study how both their ethics and psychology are conditioned by the environment and yet modify it in turn.

10. The economic theories of Marxism do not constitute a hypothetico-deductive system, but an implicit sociology. The central doctrine of Marx’s sociological economics is the fetishism of commodities of which the theory of surplus value is an abstract and derivative expression. For Marx, political economy is not an independent discipline, but a study of the formal relations between objects which have acquired negotiable char acters in the total process of social production.

11. Marxism and Philosophy. Although Marxism is primarily a method, it cannot be merely that. One goes on to ask why is Marxism as a method more effective than another; what characters does the subject matter to which the method is applied possess, in virtue of which action based upon it is successful? The philosophy of dialectical materialism is the attempt at systematic description of those fundamental characters of time, value and existence from which the categories of social and physical explanation are ultimately drawn. Marx indicated only the general outlines of such a world-view. His position may be characterized as a realistic evolutionary naturalism, strongly voluntaristic in its social implications. One may accept the fundamental doctrines of dialectical materialism without being a Marxist just as one may be a socialist without being a Marxist. But a Marxist must be both a socialist and a dialectical materialist.

The tendency to dismiss Marx’s philosophy is due to the refusal to examine Marx’s positions in the light of the history of modern philosophy, as Engels did in his Feurbach. The historical approach is not the only possible approach, but due to the special difficulties of Marx’s language the best pedagogic one. And of philosophy in general it is always well to remember Marx’s own caution that, “the fact that several individuals cannot stomach modern philosophy and die of philosophical indigestion proves no more against philosophy than the fact that here and there a steam boiler explodes and blows several passengers into space proves against mechanics.”

This is what I conceive to be distinctive in the theory of Marxism. Whether these doctrines are consistent or true need not concern us here.1 But whoever is acquainted with the refutations and criticisms of Marxism coming from both the left and right will realize that Marx’s head never seems to be where the axe falls. It is an open question whether Marx’s opponents have more violently distorted his doctrines than his orthodox friends. But as to whether both have radically misunderstood him, there seems to me to be no question at all.

1 Cf. my Philosophy of Dialectical Materialism. Journal of Philosophy, vol. 25 (1928), p. 113.

Modern Quarterly began in 1923 by V. F. Calverton. Calverton, born George Goetz (1900–1940), a radical writer, literary critic and publisher. Based in Baltimore, Modern Quarterly was an unaligned socialist discussion magazine, and dominated by its editor. Calverton’s interest in and support for Black liberation opened the pages of MQ to a host of the most important Black writers and debates of the 1920s and 30s, enough to make it an important historic US left journal. In addition, MQ covered sexual topics rarely openly discussed as well as the arts and literature, and had considerable attention from left intellectuals in the 1920s and early 1930s. From 1933 until Calverton’s early death from alcoholism in 1940 Modern Quarterly continued as The Modern Monthly. Increasingly involved in bitter polemics with the Communist Party-aligned writers, Modern Monthly became more overtly ‘Anti-Stalinist’ in the mid-1930s Calverton, very much an iconoclast and often accused of dilettantism, also opposed entry into World War Two which put him and his journal at odds with much of left and progressive thinking of the later 1930s, further leading to the journal’s isolation.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/modern-quarterly_winter-1930-1931_5_4/modern-quarterly_winter-1930-1931_5_4.pdf