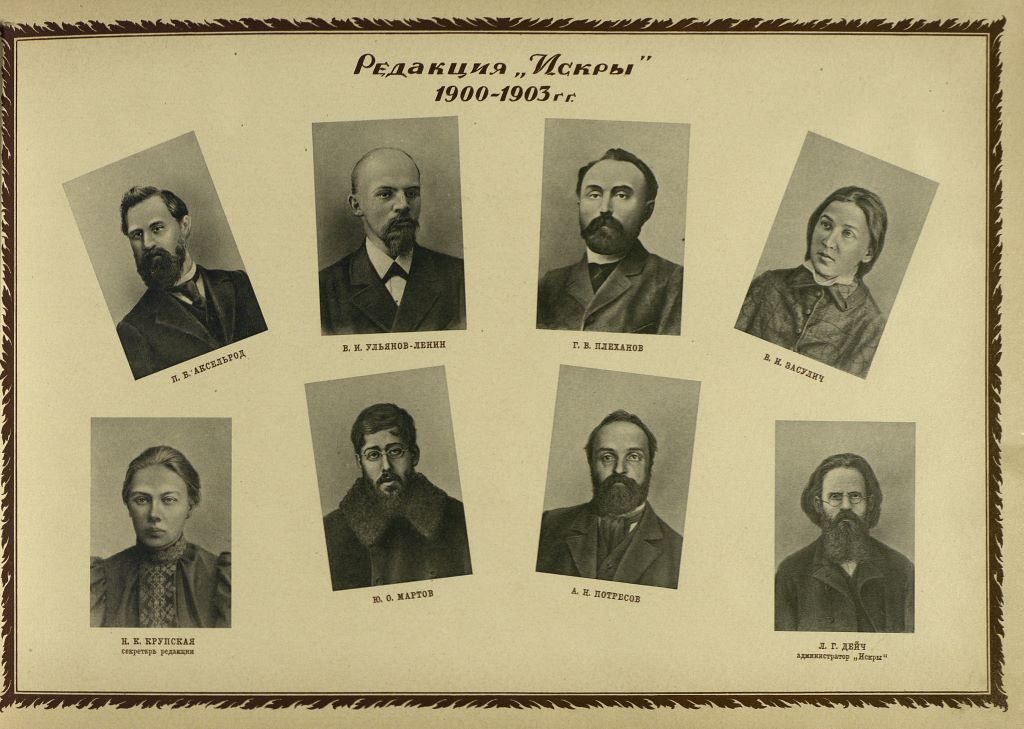

Lenin answers with ‘Iskra,’ an all-Russian political newspaper to serve as a common reference point for the various revolutionary circles and, most importantly, to act as a ‘collective organizer.’

‘Where to Begin?’ (1901) by V. I. Lenin from Selected Works, Vol. 2. International Publishers, New York. 1937.

THE question “what is to be done?” has been very prominent before the Russian Social-Democrats in the past few years. It is not a matter of choosing the path we are to travel (as was the case at the end of the ‘eighties and the beginning of the ‘nineties), but of the practical measures and the methods we must adopt on a certain path. What we have in mind is a system and plan of practical activity. It must be confessed that the question of the character of the struggle and the means by which it is to be carried on–which is a fundamental question for a practical party–still remains unsettled and still gives rise to serious differences which reveal a deplorable uncertainty and ideological wavering. On the one hand, the “Economist” tendency, which strives to curtail and restrict the work of political organisation and agitation, is not dead yet by any means. On the other hand, the tendency of unprincipled eclecticism, masquerading in the guise of every new “idea” and incapable of distinguishing between the requirements of the moment and the permanent needs of the movement as a whole, still proudly raises its head. As is well known, such a tendency has entrenched itself in Rabocheye Dyelo. The latest statement of “principles” published by that paper–a sensational article bearing the bombastic title, “A Historical Turn” (Listok Rabochevo Dyela, No. 6)–strongly confirms our opinion of it. Only yesterday, we flirted with Economism, expressed our indignation at the severe condemnation of Rabochaya Mysl, and “modified” the Plekhanov presentation of the question of fighting against the autocracy; but today we quote the words of Liebknecht: “If circumstances change within twenty-four hours then tactics must be changed within twenty-four hours”; now we talk about a “strong fighting organisation” for the direct attack upon and storming of the autocracy; about “extensive revolutionary, political [how strongly this is worded: revolutionary and political!] agitation among the masses”; about “unceasing calls for street protests”; about “organising street demonstrations of a sharply [sic!] expressed political character,” etc., etc.

We might have expressed satisfaction at Rabocheye Dyelo having so readily understood the programme we advocated in the very first number of Iskra, viz., establishing a strongly organised party for the purpose of winning, not only a few concessions, but the very fortress of the autocracy; but the absence of anything like a fixed point of view in Rabocheye Dyelo spoils all our pleasure.

Rabocheye Dyelo takes Liebknecht’s name in vain, of course. Tactics in carrying on agitation on some special question, or in relation to some detail of Party organisation, may be changed within twenty-four hours; but views as to whether a militant organisation and political agitation among the masses are necessary, necessary at all times and absolutely necessary, cannot he changed in twenty-four hours, or even in twenty-four months for that matter–except by those who have no fixed ideas on anything. It is absurd to refer to changed circumstances and changing periods. Work for the establishment of a fighting organisation and for carrying on political agitation must be carried on under all circumstances, no matter how “drab and peaceful” the times may be, and no matter how low the “depression of revolutionary spirit” has sunk. More than that, it is precisely in such conditions and in such periods that this work is particularly required; for it would be too late to start building such an organisation in the midst of uprisings and outbreaks. The organisation must be ready to develop its activity at any moment. “Change tactics in twenty-four hours!” In order to change tactics it is necessary first of all to have tactics, and without a strong organisation, tested in the political struggle carried on under all circumstances and in all periods, there can be no talk of a systematic plan of activity, enlightened by firm principles and unswervingly carried out, which alone is worthy of being called tactics. Think of it! We are now told that the “historical moment” has confronted our Party with the “absolutely new” question of–terror! Yesterday the “absolutely new” question was the question of political organisation and agitation; today it is the question of terror! Does it not sound strange to hear people with such short memories arguing about radical changes in tactics?

Fortunately, Rabocheye Dyelo is wrong. The question of terror is certainly not a new one, and it will be sufficient briefly to recall the long-established views of Russian Social-Democracy on this question to prove it.

We have never rejected terror on principle, nor can we do so. Terror is a form of military operation that may be usefully applied, or may even be essential in certain moments of the battle, under certain conditions, and when the troops are in a certain condition. The point is, however, that terror is now advocated, not as one of the operations the army in the field must carry out in close connection and in complete harmony with the whole system of fighting, but as an individual attack, completely separated from any army whatever. In view of the absence of a central revolutionary organisation, terror cannot be anything but that. That is why we declare that under present circumstances such a method of fighting is inopportune and inexpedient; it will distract the most active fighters from their present tasks, which are more important from the standpoint of the interests of the whole movement, and will disrupt, not the government forces, but the revolutionary forces. Recall recent events. Before our very eyes, broad masses of the urban workers and the urban “common people” rushed into battle, but the revolutionaries lacked a staff of leaders and organisers. Would not the departure of the most energetic revolutionaries to take up the work of terror under circumstances like these weaken the fighting detachments upon which alone serious hopes can be placed? Would it not threaten to break the contacts that exist between the revolutionary organisations and the disunited, discontented masses, who are expressing protest, and who are ready for the fight, but who are weak simply because they are disunited? And these contacts are the only guarantee of our success. We would not for one moment assert that individual strokes of heroism are of no importance at all. But it is our duty to utter a strong warning against devoting all attention to terror, against regarding it as the principal method of struggle, as so many at the present time are inclined to do. Terror can never become the regular means of warfare; at best, it can only be of use as one of the methods of a final onslaught. The question is, can we, at the present time, issue the call to storm the fortress? Apparently Rabocheye Dyelo thinks we can. At all events, it exclaims: “Form into storming columns!” But this is merely a display of excessive zeal. Our military forces mainly consist of volunteers and rebels. We have only a few detachments of regular troops, and even these are not mobilised, not linked up with each other, and not trained to form into any kind of military column, let alone a storming column. Under such circumstances, anyone capable of taking a general view of the conditions of our struggle, without losing sight of them at every “turn” in the historical progress of events, must clearly understand that at the present time our slogan cannot be “Storm the fortress,” but should be “Organise properly the siege of the enemy fortress.” In other words, the immediate task of our Party is not to call up our available forces for an immediate attack, but to call for the establishment of a revolutionary organisation capable of combining all the forces and of leading the movement not only in name but in deed, i.e., an organisation that will be ready at any moment to support every protest and every outbreak, and to utilise these for the purpose of increasing and strengthening the military forces fit for the decisive battle.

The events of February and March have taught us such a thorough lesson that it is hardly likely that objection will be raised to the above conclusion on principle. But we are not called upon at the present moment to settle the question in principle, but in practice. We must not only be clear in our minds as to the kind of organisation we must have and the kind of work we must do; we must also draw up a definite plan of organisation that will enable us to set to work to build it from all sides. In view of the urgency and importance of the question, we have taken it upon ourselves to submit to our comrades the outlines of such a plan, which is described in greater detail in a pamphlet now in preparation for the press.

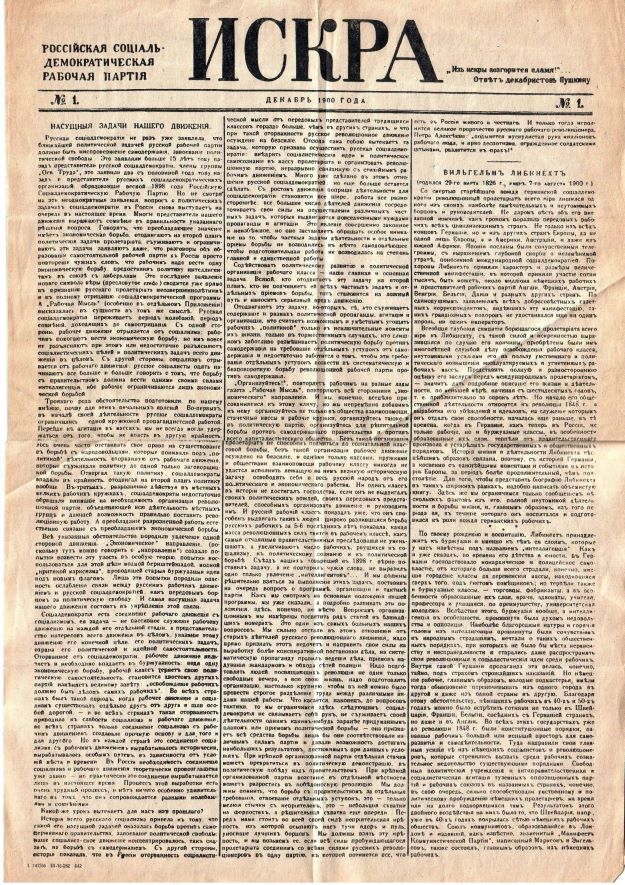

In our opinion, the starting point of all our activities, the first practical step towards creating the organisation we desire, the thread that will guide us in unswervingly developing, deepening and expanding that organisation, is the establishment of an all-Russian political newspaper. A paper is what we need above all; without it we cannot systematically carry on that extensive and theoretically sound propaganda and agitation which is the principal and constant duty of the Social-Democrats in general, and the essential task of the present moment in particular, when interest in politics and in questions of socialism has been aroused among the widest sections of the population. Never before has the need been so strongly felt for supplementing individual agitation in the form of personal influence, local leaflets, pamphlets, etc., with general and regularly conducted agitation, such as can be carried on only with the assistance of a periodical press. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that the frequency and regularity of publication (and distribution) of the paper would serve as an exact measure of the extent to which that primary and most essential branch of our military activities has been firmly established. Moreover, the paper must be an all-Russian paper. Unless we are able to exercise united influence upon the population and upon the government with the aid of the printed word, it will be utopian to think of combining other more complex, difficult, but more determined forms of exercising influence. Our movement, intellectually as well as practically and organisationally, suffers most of all from being scattered, from the fact that the vast majority of Social-Democrats are almost entirely immersed in purely local work, which narrows their horizon, limits their activities and affects their conspiratorial skill and training. It is in this state of disintegration that we must seek the deepest roots of the instability and vacillation to which I referred above. The first step towards removing this defect, and transforming several local movements into a united all-Russian movement, is the establishment of a national all-Russian newspaper. Finally, it is a political paper we need. Without a political organ, a political movement deserving that name is inconceivable in modern Europe. Without such a paper it will be absolutely impossible to fulfil our task, namely, to concentrate all the elements of political discontent and protest, and with them fertilize the revolutionary movement of the proletariat. The first step we have already accomplished. We have aroused in the working class a passion for “economic,” factory exposures. We have now to take the second step: to arouse in every section of the population that is at all enlightened a passion for political exposures. We must not allow ourselves to be discouraged by the fact that the voice of political exposure is still feeble, rare and timid. This is not because of a general submission to political despotism, but because those who are able and ready to expose have no tribune from which to speak, because there is no audience to listen eagerly to, and approve of, what the orators say, and because the latter do not see anywhere among the people forces to whom it would be worth while directing their complaint against the “omnipotent” Russian government. But now all this is changing with enormous rapidity. Such a force now exists the revolutionary proletariat. It has demonstrated its readiness, not only to listen to and to support an appeal for a political struggle, but to fight boldly in that struggle. We are now in a position, and it is our duty, to set up a tribune for the national exposure of the tsarist government. That tribune must be a Social-Democratic paper. The Russian working class, unlike other classes and strata of Russian society, betrays a constant desire for political knowledge; it demands illegal literature, not only during periods of unusual unrest, but at all times. Given that mass demand, given the training of experienced revolutionary leaders which has already begun, and given the great concentration of the working class, which makes it the real master in the working class quarters of large towns, in factory settlements and small industrial towns, the establishment of a political paper is a thing quite within the powers of the proletariat. Through the medium of the proletariat, the paper will penetrate to the urban petty bourgeoisie and to the village handicraftsmen and peasants, and I will thus become a real, popular political paper.

But the role of a paper is not confined solely to the spreading of ideas, to political education and to attracting political allies. A paper is not merely a collective propagandist and collective agitator, it is also a collective organiser. In this respect, it can be compared to the scaffolding erected around a building in construction; it marks the contours of the structure and facilitates communication between the builders, permitting them to distribute the work and to view the common results achieved by their organised labour. With the aid of, and around, a paper, there will automatically develop an organisation that will engage, not only in local activities, but also in regular, general work; it will teach its members carefully to watch political events, to estimate their importance and their influence on the various sections of the population, and to devise suitable methods of influencing these events through the revolutionary party. The mere technical problem of procuring a regular supply of material for the newspaper and its regular distribution will make it necessary to create a network of agents of a united party, who will be in close contact with each other, will be acquainted with the general situation, will be accustomed to fulfilling the detailed functions of the national (all-Russian) work, and who will test their strength in the organisation of various kinds of revolutionary activities. This network of agents1 will form the skeleton of the organisation we need, namely, one that is sufficiently large to embrace the whole country; sufficiently wide and many-sided to effect a strict and detailed division of labour; sufficiently tried and tempered unswervingly to carry out its own work under all circumstances, at all “turns” and in unexpected contingencies; sufficiently flexible to be able to avoid open battle against the overwhelming and concentrated forces of the enemy, and yet able to take advantage of the clumsiness of the enemy and attack him at a time and place where he least expects attack. Today we are faced with the comparatively simple task of supporting students demonstrating in the streets of large towns; tomorrow, perhaps, we shall be faced with a more difficult task, as for instance, supporting a movement of the unemployed in some locality or other. The day after tomorrow, perhaps, we may have to be ready at our posts, to take a revolutionary part in some peasants’ revolt. Today we must take advantage of the strained political situation created by the government’s attack upon the Zemstvo. Tomorrow, we may have to support the indignation of the population against the outbreaks of some tsarist bashi-bazuk, and help, by boycott, agitation, demonstration, etc. to teach him such a lesson as will compel him to beat an open retreat. This degree of military preparedness can be created only by the constant activity of a regular army. If we unite our forces for conducting a common paper, that work will prepare and bring forward, not only the most competent propagandists, but also the most skilled organisers and the most talented political Party leaders who will be able at the right moment to issue the call for the decisive battle, and will be capable of leading that battle.

In conclusion, we desire to say a few words in order to avoid possible misunderstandings. We have spoken continually about systematic and methodical preparation, but we had no desire in the least to suggest that the autocracy may fall only as a result of a properly prepared siege or organised attack. Such a view would be stupid and doctrinaire. On the contrary, it is quite possible, and historically far more probable, that the autocracy will fall under the pressure of one of those spontaneous outbursts or unforeseen political complications which constantly threaten it from all sides. But no political party, if it desires to avoid adventurist tactics, can base its activities on expectations of such outbursts and complications. We must proceed along our road and steadily carry out our systematic work, and the less we rely on the unexpected, the less likely are we to be taken by surprise by a “historical turn.”

May 1901.

1. It is understood, of course, that these agents can act successfully only if they work in close conjunction with the local committees (groups or circles) of our Party. Indeed, the whole plan we have sketched can be carried out only with the most active support of the committees, which have already made more than one attempt to achieve a united party, and which, I am certain, sooner or later, and in one form or another, will achieve that unity.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/selected-works-vol.-2/Selected%20Works%20-%20Vol.%202.pdf