A rich political biography from Karl Radek written on Sun Yat Sen’s death in 1925.

‘Sun-Yat-Sen’ (1925) by Karl Radek from Portraits and Pamphlets. R.M. McBride Publishers, New York, 1935.

March 14th, 1925

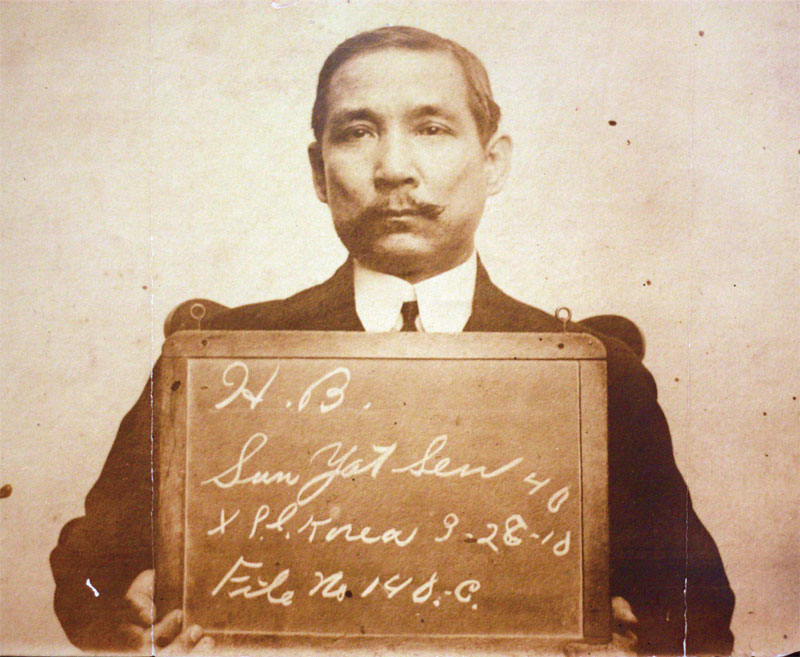

THE Chinese people have lost their best son. Sun-Yat-Sen is dead. He was a symbol of the revival of the Chinese people. The great masses of China, awakened to life by their great sufferings, will stand at his grave in deep sorrow. The capitalist Press which formerly glorified him as a great reformer will now sneer and represent him as a wild dreamer who in his old age fell under Bolshevik influence. The proletariat of the U.S.S.R. and the revolutionary part of the world proletariat will take leave of Sun-Yat-Sen in sorrow as a great leader of the people of China-a revolutionist whose forty years’ experience of revolutionary activity taught him that the salvation of the Oriental peoples lies in their union with the revolutionary proletariat of the West.

Not long ago, the more progressive currents of China joined with us in our great grief at the death of Lenin. This fact is witness that Sun-Yat-Sen is not an exception, that wide masses of Chinese society have realized who is their enemy and who their ally. We are deeply moved by the news of the death of Sun-Yat-Sen. As we lower the standard of the Communist International over his tomb we feel kinship with the struggling Chinese people in our joint loss. Just as the people’s revolutionaries of China seek to understand what it was that Lenin symbolized, what class forces he expressed, we must understand the life and work of the great teacher of the Chinese people. We must understand this in order to carry out Lenin’s great bequest to achieve the unification of the struggling international proletariat with the peoples of the East.

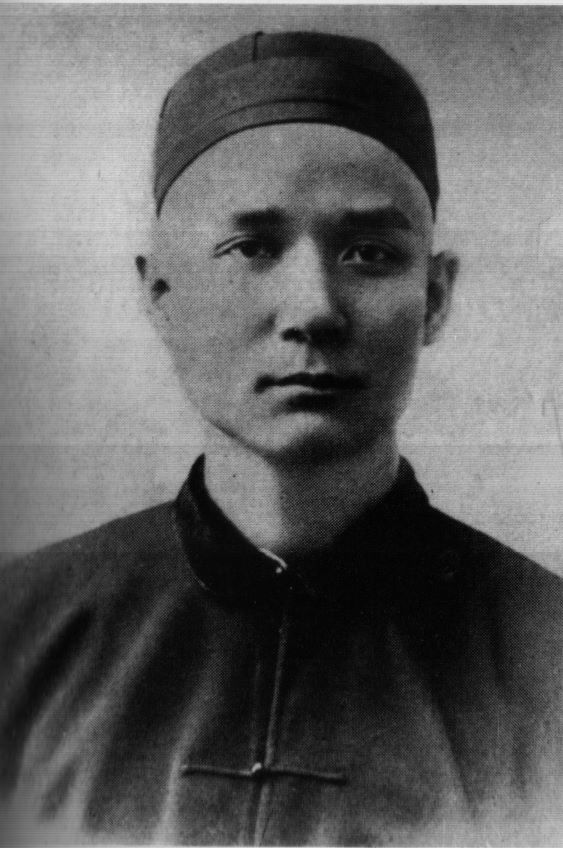

Sun-Yat-Sen was a son of poor parents. He was born in 1867 in the south of China in the province of Kwantung. He was born three years after the British Major Gordon at the head of a band of European adventurers and hired troops of the Manchu dynasty suppressed the uprising of the Taipings. When little Sun was born, homesteads were still burning, the guerilla struggle of the remnants of the rebel troops was still going on. But China lay defenceless at the feet of foreign capital. Only the economic depression which soon after began in Europe saved China from immediate dismemberment. The spies of capitalism were scouring the country, studying its wealth and its customs, choosing points for further attack. Capitalist influence penetrated the country through the open ports of Canton and Shanghai, and entrenched itself firmly first in the coastal provinces. The Pekin court was very troubled by this invasion. As for the masses of the nation, they suffered from lack of cohesion. They had lost some three million people in the Taiping revolt, and they had lost hope of freeing themselves by their own efforts alone from foreign domination or from the dynasty which by the aid of its bureaucratic apparatus was busy sucking away their last stores of strength. The French and British were advancing from the south; Japan from the north.

Among Chinese scholars with a knowledge of the international situation and a sense of the growing feebleness of their country, the opinion began to grow that only serious reform could save China. In 1880 the scholar Kang Yu-wei wrote a memorandum pointing out that the Chinese bureaucracy was mercenary and inefficient, and that the country was breaking up into many independent governorships. Kang wrote: ‘He who to-day adheres to the old methods and old views not only fails to understand the needs of the State, but has moved far away from the views of our wise men of olden times.’ He pointed to the reforms in Japan and stated that only similarly radical steps could save China. The directors of the Pekin Academy refused to pass Kang’s memorandum on to the Emperor; it seemed heretical. China, they said, might have lost her former strength, but she still had the only true knowledge that taught her by her great ancient teacher Confucius-and the overseas barbarians could not possibly be dangerous.

Then came the Sino-Japanese war. China was not merely conquered; her weakness and feebleness were exposed to the whole world. A peace scandalously humiliating for China was concluded at Shimonoseki. At a great gathering of scholars assembled in Pekin for the state examinations, held on May 29th, 1895, Kang presented a second memorandum demanding reform of the Chinese bureaucracy. In his memorandum he said ‘Chinese departmental positions are occupied not by those who know what to do to help peasant and craftsman, not by men with administrative ability, but by those who can pay the most for a soft job. Some are taught what they will never use, and others are not using what they were taught.’ He pointed to the progress of modern industry and trade and demanded their encouragement in China. He demanded abolition of the customs barriers between provinces and aid for the peasantry.

Under the influence of their defeat in war the Government censors did transmit this memorandum to the dowager and her son-emperor. The emperor ordered the memorandum to be sent to the provincial governors with instructions to put the proposed reforms into practice. He would have liked to receive the reformer personally, but this was forbidden, because Kang Yu-wei was not of the proper rank. But Kang obtained a position in the Ministry of Social Politics which gave him the right to present memoranda, and one after another he prepared them, in an attempt to familiarize the dynasty with the dangers menacing the country. He pointed to the tsarist and Japanese threats in the North, the threat of France in the South, the occupation of Kiao-Chow by Germany. China could be saved only by the formation of a modern army.

‘Since our shameful defeat in the war with Japan,’ he wrote, ‘the European powers look upon us with disdain as upon savages and treat us as stupid peasants; they place us on a level with negroes. Formerly they hated us as an arrogant people, now they make mock of us as stupid, blind and dumb. Foreigners from all over the world are trying to get concessions. They demand our bones, our flesh. They are carving pieces from our body and will go on till nothing remains. Foreigners are getting railway concessions. From north and south we are threatened by destruction. We must remember the fate of Turkey, Korea, Annam and Poland.’ Kang wrote Reflections on the Reorganization of Japan, Reflections on the Reorganization of Russia under Peter the Great. He wrote a biography of Peter the Great and sent it to the young emperor. The emperor appointed him as his advisor and began feverishly trying to put the proposed reforms into practice.

From the emperor’s palace emissaries were sent into the provinces with instructions to organize the Press and the schools, and to reorganize the army. This attempt at reforms from above lasted only a hundred days. The bureaucracy revolted against it. These reforms have put the masses on their feet, checked the high-handedness of the bureaucracy and limited their takings. But each man of them had paid a great deal for his place. The most influential strata of the scholars, the ‘custodians of tradition,’ saw these attempts at reforms as sacrilege against the old doctrines. The old empress, Tsi-si, headed these bureaucratic conspirators, organized a change of government, arrested the young emperor Hu An-su, and locked him in a beautiful palace on an island, where he died true to Kang’s teaching.

The theory that a dominant class is unable to reform itself, renounce its privileges, unless forced to by mass pressure, was proved once more by history. Kang fled abroad, and China went on decaying, victim of its own bureaucracy and of foreign capital. The old empress could see the growing discontent of the masses. She attempted to direct it against foreigners, and subsidized the organization of the ‘Boxer Rising.’ This rising was most barbarically suppressed by an international military expedition and merely delivered a help- less, completely crushed China over to foreign capital.

With the twentieth century began the partition of China. Almost the whole of international imperialist literature of the time was devoted to the dividing up of China among the imperialist powers. The economic development that began in the last decade of the nineteenth century compelled England, Germany and France to search for new markets. Tsarist Russia was afraid of not getting her share, and hastened to seize Korea and Manchuria. The Russo-Japanese war which concerned Chinese territory was prepared. Seemingly there was no salvation for China.

In the south, where the Taiping revolt had originated, where the reformer Kang was born, Sun-Yat-Sen grew up. When he had passed through a village national school, he spent several years in the Hawaiian Islands, where his brother was engaged in trade, and then returned to Hong-Kong and studied medicine in the English schools. But Sun-Yat-Sen, young, sensitive and warm hearted, was not satisfied with science. He looked about him and pondered on the destiny of his country. The popular rising of the Taipings filled him with deep disappointment. How could the illiterate Chinese people ever struggle against European powers armed with modern science and technique? He decided that it was first of all necessary to enable the people to rise culturally, to study; only that way would China become equal to the advanced nations of the West. But how were the great masses of China to be liberated? Sun did not belong to the scholar caste and did not believe in the revival of China by means of reforms voluntarily carried out by the old civil service led by the last dynasty.

He came to the conclusion that the first step would have to be the overthrow of the barbarous Manchu dynasty which had seized China in the seventeenth century. His idea was conspiracy, but he found only three associates prepared to follow him on that dangerous road. During the Sino- Japanese war he established a Society for China’s Revival. Propaganda began in the army; guns were purchased. The conspiracy failed and on September 9th, 1895, Sun-Yat-Sen’s comrade Luko Dun was executed. Sun-Yat-Sen escaped abroad.

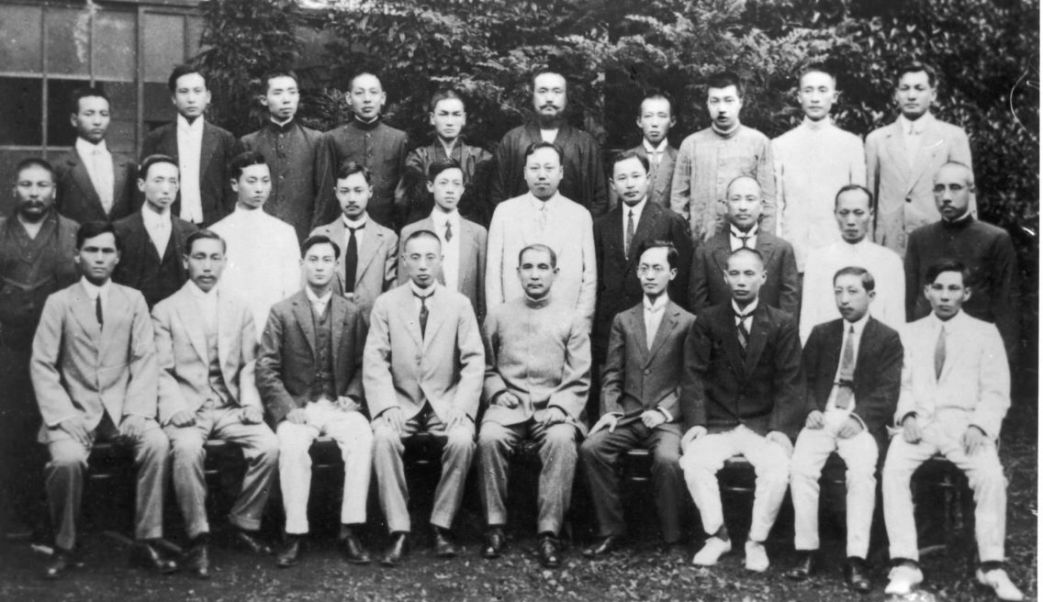

Years as a refugee, years of study, now followed, mostly spent in great poverty. Young Sun travelled to all the countries where there were Chinese living–Japan, the British colonies, America, England. Living by his scientific work, and a certain amount of help from supporters, Sun tried to get into touch with young Chinese studying abroad, and with Chinese traders. He made a careful study of the govern- mental structure of European and American states. He began to see that behind the facade of capitalist prosperity lay hidden the want of the masses. He himself had been born in poverty, and it was no matter of indifference to him. He was in sympathy with socialism, only he considered that socialist tendencies were premature in China because of the lack of an industrial proletariat. Democracy–especially American democracy–was his ideal of governmental structure. The way to the ideal led through conspiracy–and first of all through military conspiracy.

Kang’s experience had completely persuaded Sun-Yat-Sen that all attempts to reform the country under the Manchu dynasty were bound to fail. But on whom could he rely? Only a generation which understood the necessity for democratic reform would be able to bring about the change. This meant those students and young soldiers studying the art of war who were convinced that China’s salvation lay in breaking with the old way. Sun-Yat-Sen put students who were influenced by him on the right road, entered into relations with the garrisons, and himself went from town to town carrying on his propaganda. He was well versed in the international situation and conscious of the contradictions between the capitalist powers. So he intrigued in Japan, hoping to find aid in the country which by decisive internal changes had saved itself from foreign capital. He did find a certain amount of support in Japan, even in ruling circles, for they considered that his propaganda would help to weaken a China already in decay. He found support too in certain American circles, which hoped on the contrary that the revolutionary movement would at least compel China to reform and that this would strengthen the country. Being economically strong, America was not afraid of other countries’ competition and was against any attempt to divide China. She came out for the policy of the ‘open door,’ i.e., for the admittance to China of the foreign capital of all countries on equal terms.

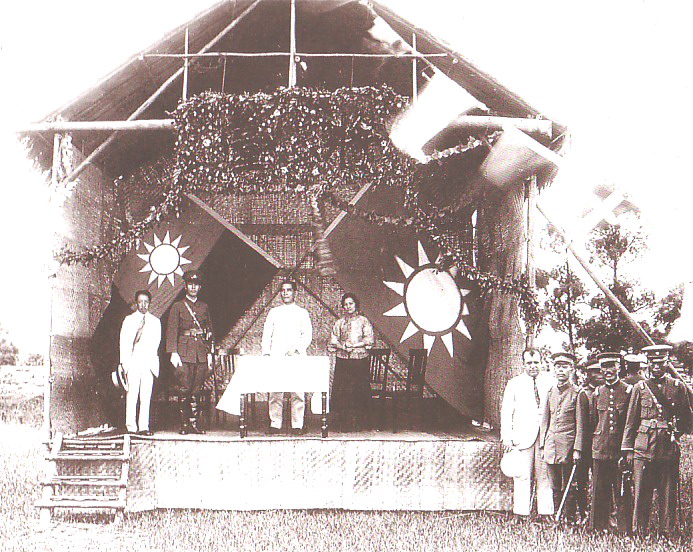

Sun-Yat-Sen’s group was successful in the army. Just like the Russian Decembrists who found response among the young officers who had been engaged in war against the French Revolution and Napoleon, and who comparing Russia with the West became persuaded that without reforms Russia would remain as a huge but helpless child, some of the young Chinese officers educated in Europe saw the great danger threatening China and joined the revolutionary camp. Financial disorder and a series of famine years caused dis- content in the army. In 1911 an uprising broke out at Uchango. It spread and gained one victory after another. Sun-Yat-Sen hurried from America via London to China, where he was the very symbol and leader of the uprising. After the victory and the overthrow of the dynasty he was elected president of the Chinese republic.

Sun-Yat-Sen seemingly had attained his aim. A parliament assembled at Nanking. But Sun-Yat-Sen’s victory now became defeat. The Manchu dynasty had been overthrown, but the whole apparatus on which it relied–the provincial bureaucracy, and the corps of military officers–remained untouched, because the revolt was one of the army only, and the masses of the people were only just beginning to move. The intelligentsia was hardly represented at all in the parliament.

The great powers which had refused to support the falling dynasty by loans would not grant any loan to Sun-Yat-Sen. They were afraid thorough reorganization might strengthen China; they saw in the Chinese revolution a most threatening manifestation of the influence of the Russian revolution of 1905 in the East, which might spread to India and the Asiatic colonies of France. International capital came to an understanding with the Chinese permanent official class and with the officer class. Yuan Shi-kai was the figure-head of this union. Sun-Yat-Sen had no effective forces to put up against Yuan Shi-kai and so had to yield the presidency to him and retire from the Government. The military conspiracy had been strong enough to sweep away the corrupt dynasty but was powerless to clear reaction out of the whole country or remove more than a few of the parasites that clung to the body of China. The foreign powers granted a loan to Yuan Shi-kai.

New years of emigration, of suffering, and of contemplation, came for Sun-Yat-Sen. The world war broke out. Japanese troops proceeded to ‘liberate’ China from the Germans but only in order to occupy Shantung themselves and prepare for seizing the whole of China. The great powers had their hands full in Europe. The United States had only just begun to build up a great fleet and enlarge its army, and could not yet offer resistance to Japan’s pretensions. In an agreement between the American Secretary of State, Lansing, and the Japanese Ambassador to America, Ishi, the United States recognized that Japan had special interests in China. Japan was at China’s throat trying to force her acceptance of a list of twenty-one demands which would have meant the complete bondage of the Chinese people.

China, seeking for salvation, declared war on Germany. She was, of course, not in a position to carry on any war, but as an ally of the great powers expected their support against the Japanese imperialists. Suddenly a ray of hope illuminated the seemingly dark future of China: Wilson began preaching the self-determination of nations. The great democracy of the North proclaimed ‘a mighty word.’ The hopes of the masses and of the Chinese intelligentsia were raised.

Then the day of the Versailles Peace arrived and gave the province of Shantung, with its forty million Chinese, into the hands of Japan. The disappointment and disillusionment of the Chinese were unbounded. Sun, who had carried on his propaganda all the time and was in constant touch with his own South, could see no way out. Echoes of the great Russian Revolution reached China. The British and American telegraph agencies disseminated the foulest and grossest libels about it, but the very ferocity of their attacks were proof for Sun-Yat-Sen that a new force opposed to world imperialism was growing on the plains of Russia. He began to pay close attention to all news really coming from that country. The victors of Versailles declared war on Soviet Russia, or, rather, began a war to exterminate it without declaring war. But the new Russia put up a defence, which from the masses, though fatigued by the imperialist war, called forth enormous fresh stores of strength. And after two and a half years of heroic struggle they conquered the Entente. Sun-Yat-Sen’s spirit revived. In the Russian revolution he perceived a new ally.

At first it was only an external ally for him. Sun did not yet understand the reason for the strength of the Russian revolution. Although he had seized power in the south of China, at Canton, he was still unable to make effective contact with the masses, for whom he was no more than a great patriot, a defender of China’s independence. He was still full of notions about liberating China by means of diplomatic intrigues and military campaigns. He thought that after his advent to power the foreign powers would stop their attempts to divide China and would render economic assistance to China, which would put her on her feet. But the defeat of Kolchak by the Red Army broke down the barrier between China and Soviet Russia. Regular communication was re-established between the two countries; Russian revolutionaries went to China, and Chinese to Russia.

Sun-Yat-Sen, old now, continued his studies. He realized his dependence upon the Chinese upper classes and the Canton merchants, who would not permit any really radical reforms, though without reforms Sun could not see his way to lead any national revolution. And without a national revolution China was unable to cope with the military clique, which after the fall of the dynasty had dismembered the huge country and was battening on the disconnected provinces. Union with Soviet Russia, which was what Sun was aiming at, could not remain a mere external political alliance. It set the industrial workers in motion (the factory proletariat in China was estimated at three million), it began to influence the peasants who had formerly been able only to form partisan or spontaneous guerilla detachments and uprisings.

The Workers’ and Peasants’ movement provoked counter- action by the bourgeoisie. They began to organize and arm against Sun in Canton. Sun then took a decisive step. He founded a revolutionary army to be used against the bourgeoisie and proposed a programme of peasant reforms and an advanced labour policy. Sun-Yat-Sen organized the forces of the people not only in Canton province but also throughout China. He met resistance in those circles of his own party which had middle-class connections, and so struggled against the people’s revolution. But Sun had made up his mind. Neither the threats of British imperialism, which was preparing to attack him, nor the danger of a split in the party, should deter him. He had chosen his path and, however thorny it might be, he was going to stick to it. But death has now overtaken him.

Before us is the life of a man who will go down to history as a great symbol of the awakening of the largest nation on earth. Before us is a life full of travail, suffering, hard thinking, and struggle. Before us is a great deed started but not yet completed. Chinese workers and peasants, the active intelligentsia whom Sun aroused, who consider him their teacher, will complete it.

But the especial greatness of this life is that the man who lived it was incessantly moving forward. After each defeat he rose again learning from his experience, studying anew. The revolution of the Taipings had begun in the South; it had had the same aims as Sun came to after his experience with the policies of conspiracy and diplomatic use of the contradictions between the imperialists. But the revolutionary movement in China to-day is in a different position from that of the Taipings. Hung, the great predecessor of Sun-Yat-Sen–the leader of the Taiping revolution-who perished in 1864, looked on the sufferings of the Chinese peasantry and evolved his ideal of a Kingdom of Labour–on the basis of the Bible!

The revolt of the Taipings was suppressed because it had no working-class support in Europe. The European working class did not even know of the tragedy of a nation which was being enacted on the shores of the Yang-Tse-Kiang. But the Chinese revolutionary movement of to-day has mighty backing in the Russian revolution, it has the growing strength of the world proletariat behind it. European imperialists cannot now attack revolutionary China without running the risk of serious trouble in ‘their own’ countries. And the forces of China itself have grown immensely during this time. In order now to hold China in its hands foreign capital would have to mobilize an army of millions. What Sun-Yat-Sen began will therefore be completed. The Chinese people may expect much suffering, the Chinese revolutionists have much to learn before they obtain the full support of the masses of China, but the seed sown by Sun-Yat-Sen is growing and the plant will produce rich fruit.

In 1916, at the height of the world war, at a small Bolshevik meeting in Berne, when discussing the question of the self determination of nations, Lenin threw out the idea of our joining forces with the future Chinese revolution. It seemed a mere fantasy. The Swiss group of refugees, five or six Bolsheviks, in Comrade Shklovski’s rooms, and the idea that the Russian proletariat and the multi-millioned masses of China would ever fight together! Who of us that were present at that meeting really thought we should see the dream fulfilled?

In 1918, when the Czechoslovakians, the Social-Revolutionaries and Kolchak were between us and China, Lenin asked if it would not be possible, among Chinese coolies come to slave in tsarist Russia, but awakened now by the October Revolution, to find some brave enough to form links with the forces of Sun-Yat-Sen. This contact with the masses of the Chinese people is now established. And it must be our life- aim as well as that of the Chinese revolutionists, to bring scores of millions into this union. Then half the victory of the world proletariat will have been won. Our graveside farewell to Sun can be made with calm assurance that his like-task will be accomplished.

One of the greatest historical services of Lenin is that in the union of the European proletariat with the oppressed people of the East he saw the lever with which the world will be moved. In their struggle for emancipation the Chinese people can be proud of Sun-Yat-Sen as the first great leader of peoples of the East to understand Lenin’s thought and to do all in his power to put it into practice. It gives him an honourable place among the greatest people of history and better than any other power will make his name live long in the memory of all peoples once oppressed.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.77166/2015.77166.Portraits-And-Pamphlets_text.pdf