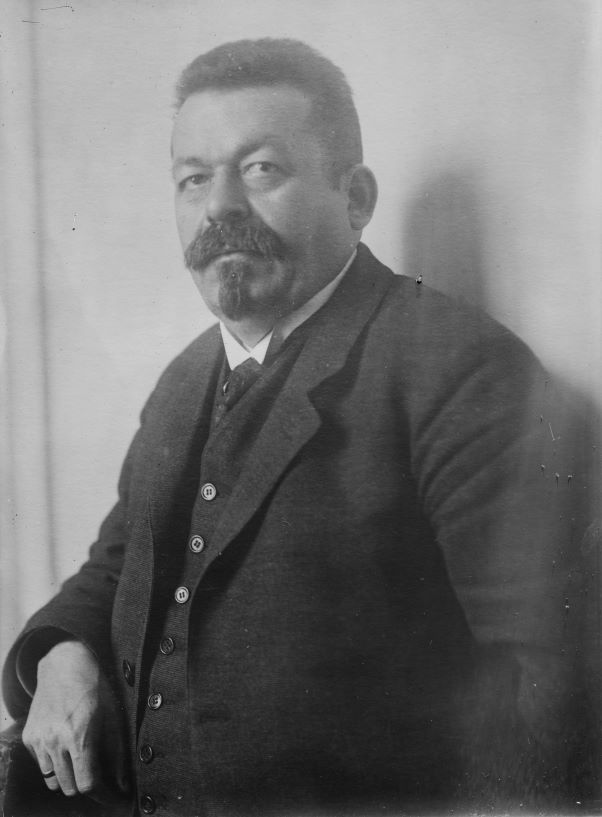

Over the still warm corpse of Fritz Ebert, Karl Radek pours scorn on the man whose ‘political biography…is the history of the fall of German Social-Democracy.’

‘Friedrich Ebert’ (1925) by Karl Radek from Portraits and Pamphlets. R.M. McBride Publishers, New York, 1935.

THE telegraph has brought the unexpected news of the death of Fritz Ebert, German Social-Democratic leader and President of the German Republic, at the very height of the struggle that was developing around him in connection with the end of his term as President. In Ebert the most typical member of German Social-Democracy has left the stage, a man who can without exaggeration be said to have been the helmsman of that onetime great workers’ party when it set its course for bourgeois waters. The policy of German Social-Democracy during the war was known as Scheidemann’s policy, yet Scheidemann was but the pennant at the masthead. If any single individual determined that policy, it was Fritz Ebert. The political biography of this man is therefore the history of the fall of German Social-Democracy, just as the biography of August Bebel is the history of its creation.

Ebert was born in 1871 in the south of Germany. His father was a tailor. South Germany was economically the most backward part of the country, still largely in a petty-capitalist stage of organization. Tailors were not industrial workers but handicraftsmen. Fritz Ebert’s whole surroundings were of the petty-bourgeois democratic type. The class antagonism between the handicraftsmen proletariat and the bourgeoisie in the south was not so pronounced as already in the Ruhr basin in the north or in Saxony. Politically the south was dominated by lower middle-class democracy. Ebert was brought up in the atmosphere of the oppression of Social-Democracy, because he was seven when Bismarck passed through the Reichstag the Emergency Law against the socialists.

But the law was not applied in the south as ferociously as it was in the north; and when Ebert began to go into politics the law was already repealed. This repeal of the Emergency Law aroused great illusions in a section of the German Social-Democrats, and the marked economic improvement which accompanied the repeal intensified those illusions. Ebert made himself prominent as a trade union worker. He was a saddler by trade, and he gave up working himself, and devoted himself to wholetime organizing work among saddlers. Trade union work was exceedingly congenial to Ebert’s temperament. A southerner who did not like abstractions, but facts, hard-headed, practically minded. Inspiring dreams were foreign to his nature; he was born for just the atmosphere that was then to prevail in German Social-Democracy.

Handicraftsman Bebel studied Lassalle’s books with their grand prospects of working-class advancement, and imbibed the principal ideas of the Communist Manifesto. While in prison, young Bebel flung himself like a starving man on the history of civilization and read everything available to enlarge his horizon. His book Women and Socialism, even in its first edition, showed the vast expanse of his creative imagination, his eagerness to understand both the past and the future of mankind.

But the generation which grew up politically in the nineties, after the overthrow of the Emergency Law against socialism and in the period of economic development, fed neither on economic theory nor on the history of revolutionary or labour movements, but on politics of social reforms, problems of labour legislation, and immediate trade union aims–on concrete issues, figures, facts, dates, and stubborn organizational work.

August Bebel was a many-sided man. He was equally capable of writing a book on the conditions of bakers or the caliphate period of Arab culture. Ebert was able to write only a statistical work on the conditions of the workers of Bremen. As Social-Democracy and the trade unions grew, as the country developed economically, reformist tendencies developed within German Social-Democracy. Vollmar was its first inspirer, Bernstein a later. A struggle within the ranks of the working class of Germany began over the revisionist question. Ebert, who was at that time elected to the editorial board of the Bremen Party paper, and later to the secretaryship of the Party in Bremen, joined that intermediate section of the Party which defended the principles of communism by word of mouth, but in practice followed a purely opportunist line. Even at that time in Bremen, Ebert was known as a ‘sound and practical politician.’ Other editors of the Party paper–Diderich, Heinrich Schultz, Henke–attempted to turn the Party paper leftward. But when it came to a choice between revolution and social-patriotism, all these gentlemen lined up under Ebert’s command, and proved that their radicalism was hardly any different from that of Ebert.

During the Bremen Party congress of 1904, old Singer, Bebel’s friend, the second chairman of the Central Committee of the German Party, ‘discovered’ Ebert. He liked Ebert’s good sense, his organizational ability, his firm will, and he recommended Ebert to Bebel as a suitable candidate for the Central Committee, to deal with organizational problems. At the Jena congress in 1905, Ebert was elected to the Central Committee of the Party. Ebert now became well known in the Party and won great respect for his organizational abilities, his even temper and his firm will. When Bebel fell ill, the practical policy of the Party passed more and more completely into Ebert’s hands. In the struggle against the revisionists he took up a very conciliatory position and when after Bebel’s death Hugo Haase, a Koenigsberg lawyer, with a reputation as a radical socialist, was elected first chairman of the Party, the revisionists rested their main hopes on broad-shouldered, low-browed Ebert, whose very fat radiated energy and will. Ebert avoided any open conflict with the revisionists, or with the trade union bureaucracy, with which he was closely connected in outlook and political method. He favoured the revisionists wherever possible.

I met Ebert in very characteristic circumstances in 1911. In Württemberg owing to the development of the metallurgical industry a militant spirit was growing among the working masses. In Stuttgart and Göttingen the leadership was in the hands of radicals, while the District Committee of the Party was in the hands of reformists. The Party paper in Göttingen, edited at that time by Talgheimer, was not only carrying on a relentless war with reformism but was also taking part in that struggle with Kautsky in which German communism was later to be forged. The District Committee discovered that the paper was in financial difficulties. Workers managing the paper did not know the laws, got into debt in circumstances which might have been utilized by the Public Prosecutor to earn them penal servitude. The reformists decided to take advantage of this and subsidize the paper in order to change its line. When Ebert arrived at Göttingen to settle the conflict between the local organization and the District Committee we showed him how the reformist leaders were trying to suppress the revolutionary paper. Ebert said coldly: ‘I came to settle this conflict, and here you wish to open a campaign against the reformists. I close the meeting and I tell you that the Party leadership will lance this abscess.’ We as well as the local workers felt at once that we had to ally with an absolute class enemy. Without a word the workers spontaneously blocked the doorway with a table and demanded our declaration to be recorded. We already had a feeling that the Left was going to be expelled from German Social-Democracy and warned Rosa Luxemburg about it, but she took our forecast rather sceptically.

In 1912 Ebert urged the Party to form an election bloc with the liberals–German Social-Democracy’s first open step towards a reformist policy.

From the very first day of the war Ebert supported German imperialism. Though quite a number of Social-Democrats did hesitate, Ebert had no doubts. That man was deeply convinced that the interests of the German working class demanded that it should stand shoulder to shoulder with the German capitalist classes. If the German capitalist classes were threatened by the danger of collapse all else for the moment was of lesser importance, and it was essential to support the bourgeoisie. Hugo Haase turned all ways, as if his socialist conscience told him that if he voted for the war credits he was betraying every principle of socialism. On the other hand there was his fear of the revolutionary struggle, and this allowed him to betray the working class rather than sacrifice the organizational unity of the Party. Ebert stood like a rock. Throughout the war he collaborated with the imperial government. We can say that this man did not have a single moment of doubt. All attempts of the opposition in the Party to divert him from his chosen way broke against his firm will. Support of the government till the conclusion of peace, support of any move to conclude a compromise peace, decisive struggle against any revolutionary tendencies of the proletariat–this was the road along which he moved, without turning either to right or left. By this policy Ebert gained enormous confidence among the ranks of the German bourgeoisie.

When the revolution broke out, Ebert, who had continuously fought against it, passionately and energetically, Ebert, who during the January strike had joined the strike committee in order to deceive the strikers and break up the strike in the interests of imperialism, now with his characteristic firmness changed his course and took on leadership of the revolution–for one purpose only–to keep the reins in his own hands. At the earliest possible moment he obtained an understanding with the general staff, and with the civil service, gave out the slogan of law and order, and attempted to come to an understanding with the Entente with the sole object of suppressing the revolution. In his eyes revolution was the worst thing that could happen, and it had to be suppressed as soon as possible, because revolution meant civil war, prolongation of the famine, whereas socialism, why, socialism was organization, organization and still more organization. But in his opinion organization was a possibility only thanks to ‘democracy’ and could only be achieved bit by bit. Therefore Ebert definitely and unequivocally aimed at taking power out of the hands of the workers’ councils and putting it into the hands of the capitalists. When in January, 1918, the working masses of Berlin rose in revolt against that policy, Ebert, again without any doubts, used Noske to suppress their discontent by armed force. Noske was only a weapon in Ebert’s hands—just as Ebert was merely executor of the will of the bourgeoisie.

The German bourgeoisie rewarded Ebert according to his deserts. They elected him President of the Republic. And observe, now that they consider the danger of revolution has passed, and that they can manage without the assistance of Social-Democracy, they are directing a considerable part of their efforts towards blackening both the name of Social-Democracy and of Ebert. But earlier, in 1922, I heard Stinnes utter words of the deepest esteem about Ebert. Stinnes told me, ‘Ebert and Legien are the only leaders of German Social-Democracy who have a sense of responsibility and are not afraid to be consistent. Without them Germany would have perished.’

Ebert was not merely a decorative president; behind the scenes he exerted a considerable influence upon the course of events. This influence he used for three aims; to suppress revolutionary movements, to keep on good terms with the Entente, and above all to safeguard Social-Democratic influence over the State administration. This policy reflected the interests of that important class, the labour aristocracy, the trade-union bureaucracy, which occupied tens of thousands of posts in the administrative apparatus of Germany. Though he had little personal interest in parade, Ebert observed all the ceremonials and customs in keeping with his position as president of a bourgeois republic. German workers who saw Saddler Ebert riding round in the Tiergarten attended by aides-de-camp or gracing the triumphant launches of Stinnes’ new ships, could say: “That is our work.”

Two million German workers perish in the imperialist war, twenty thousand workers are killed by the gangs of Whites led by Social-Democratic Noske in the civil war, seven thousand workers languish in the prisons of the Republic, ah yes, but, you see, Social-Democracy rules, and Ebert is President! Yet with bitter sorrow we have to record that there are still millions of workers in Germany who believe, though it is not very pleasant to see Ebert on horseback escorted by officers of the Junker class, still he is ‘ours and will do good.’ But though leaders of the working class may forget their class, the class they have sprung from, the class which has promoted them, the bourgeoisie which uses such leaders in the moment of danger, will always when the danger is over, show that it has not forgotten where they sprang from. Those very Ludendorfs whom Ebert saved in 1918 from the revolutionary masses, those Stinnes whom he has helped to maintain in power, consider that even so there is an odour of revolution about him, and a saddler on the throne of the Hohenzollerns is a challenge to capitalist Germany.

The revolutionary workers were unable to develop a furious campaign against Ebert because the capitalist Press took it out of their hands and began to depict that faithful servant of the German capitalist fatherland to the petty-bourgeois capitalist masses, the lesser middle class, as a revolutionary betrayer of his land. The saddlers’ union which Ebert organized expelled him from membership as a betrayer of the working class. The German bourgeoisie, now that death has made it unnecessary for them to remove him from the presidential post, will no doubt amnesty him and erect to him the monument he has deserved. He will enter the history of the working class as one of its greatest traitors, the more characteristic for not being motivated by pure self-interest. He was merely a sort of concentrate of mistrust of the working class, and it was this mistrust in the revolutionary possibilities of the proletariat that produced his servility to the bourgeoisie. The generation which has developed in the epoch of war and revolution will not produce Eberts. It will produce either honest revolutionary workers or opportunist scoundrels and unprincipled adventurers. Ebert became a scoundrel from reformism, his successors will be reformists because they are scoundrels.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.77166/2015.77166.Portraits-And-Pamphlets_text.pdf