Labor historian and workers’ educator David J. Saposs looks at the role of different European immigrations–German, Irish, Jewish, Eastern, and Southern Europe–and the nativist reaction had on the U.S. union movement.

‘The Immigrant in the Labor Movement’ by David J. Saposs from Modern Quarterly. Vol. 3 No. 2. February-April, 1926.

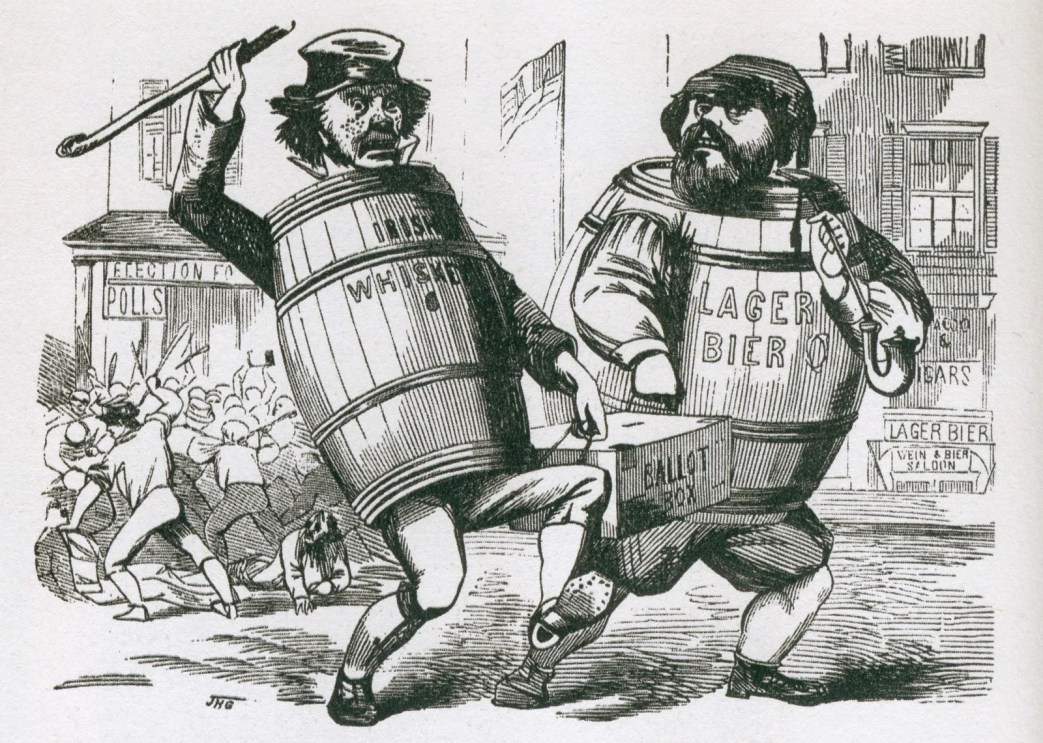

The American labor movement like the American nation is a creation of the immigrant. Likewise the American labor movement has been considerably influenced by the European movement. These are commonplace observations, and whereas stereotyped generalizations are usually misleading these are substantiated by historic facts. What might be called an indigenous labor movement functioned in the early history of the country. The participants and their leaders, in so far as it is known, were Americans of several generations. But the late Thirties mark the beginning of new mass immigration from three sources in the following importance: Ireland, Germany and England. The Irish fled from the domination of a foreign conqueror and starvation from famine. The Germans sought refuge from monarchial tyranny and persecution following the republican uprisings. The English, in common with the Irish and the Germans came in quest of economic opportunity. Nor were these early immigrants received any more cordially than the more recent immigrants. Even the English, although descendent from the same stock as the Americans, were unwelcome. In the case of the Irish and the Germans, the one Roman Catholic and of peasant stock, the other speaking a strange tongue and adhering to quaint customs–the hostile reception and persecution was bitter and persistent. Instead of the Ku Klux Klan there were the “Know Nothings” and “Native Americans,” and race rioting was but one form of anti-foreign manifestation.

But these sturdy immigrants were undaunted and immediately proceeded on their own initiative to adapt themselves to their new surroundings. The English immigrant workers, having trades, knowing the language and customs, and having had experience in the labor movement at home, soon became an influential part of the American labor movement. The Irish, emanating from backward agricultural communities possessed neither trades nor previous contact with the labor movement, became the common laborers of the country–the builders of our roads, canals and railroads. Gradually their children advanced up the rungs of the industrial ladder becoming the skilled workers. And because of their political predilections they also became the leaders of the American labor movement. Not having acquired a social philosophy in the country of their origin, they naturally accepted the views current in the labor movement. Because of the influence of the English workers and the convictions, borne of bitter experience, of such young immigrant leaders as Adolph Strasser and Samuel Gompers, the English-speaking branch of the American labor movement followed the British model of trade unionism. Their ideal was national craft unions with high dues, a strong treasury for strike and other benefit features, and concentration upon immediate improvements in working conditions, like higher wages, shorter hours and sanitary work shops. They accepted the present wage system eschewing independent, working class political action and any philosophy that aimed to overthrow capitalism. This has now become known as “pure and simple unionism,” and trade-marked “the genuine American article.”

The other strand of early mass immigration–the Germans— also did not wait for assistance but set about to adopt themselves to the new conditions. Unlike the Irish many of them came from industrial centers and were trained workers. And like the English they had been part of a virile labor movement. But instead of featuring pure and simple unionism their movement sponsored radical and socialist unionism and independent working class political action. The German mass immigration also included experienced labor leaders and intellectuals who were thoroughly familiar with the theoretical and practical aspirations of the labor movement. In addition, the German workers became the dominant factor in many industrial centers, as well as in many important industries, as wood-working, cigar-making, baking and brewing. Having had experience in the labor movement in the fatherland, and finding themselves the controlling factor in many unorganized industrial centers and trades, they naturally set about to found their own unions, their own labor press and other educational auxiliaries, and their own political or Socialist clubs.

Thus this country witnessed the simultaneous development of an English-speaking labor movement featuring pure and simple unionism, and a German-speaking labor movement sponsoring industrial and radical unionism, and independent working class and Socialist political action. Clashing over ideals these parallel movements nevertheless generally cooperated in practical matters. On the whole the German labor movement showed greater militancy, usually pioneering even in the practical or immediate demands of the labor movement. Hence, it was the unions with exclusive or large German membership that pioneered in the great eight-hour demand and strikes of the Eighties. The Germans were also the leaders in the cooperative movement of their time.

The recent immigration has in many respects repeated the course of the early immigration. The bulk of the southern and eastern European immigration comes from agricultural districts, is of peasant stock and Catholic. They resemble the Irish with the additional handicap of speaking strange tongues. Because of their helplessness they at first became the prey of mercenary fellow countrymen and greedy employers. Unacquainted with modern industry and knowing nothing of labor organization they remain unorganized, unless the existing unions, of which the United Mine Workers and the I.W.W. are the most noted examples, offer them a helping hand. Once they become schooled in the methods of organized labor they remain its staunchest and most progressive adherents. While at first labor leaders and students of labor were doubtful of the organizability of these recent immigrants, this doubt has been completely discarded since the great coal, steel and railroad strikes in which the largest portion of the strikers were immigrants. Indeed, it is generally conceded now that they are more responsive to attempts to organize them than unorganized American workers, and make better unionists than the latter. These recent immigrant workers are at present the backbone of most of the unions in such basic industries as mining, metal trades, railroad shops, meat packing and wood-working.

These immigrant workers at first followed unquestioningly the leaders of the unions which organized them. But after having become oriented they began to assert themselves through their own leaders and press. In the pure and simple unions they generally aligned themselves with those English-speaking workers who hold that their unions should supplement their activities for the betterment of immediate conditions with support of causes that advocate the attainment of a new social order. It is this combination that committed the United Mine Workers to nationalization of mines and independent political action at its convention in 1919. On the other hand the immigrant workers that were led by the I.W.W. abandoned it after a few years of practical experience. Their disappointment in the I.W.W. was not because of its radicalism, which had captivated their imagination and to which they subscribed wholeheartedly. On the contrary, they disapproved of its lack of sympathy for practical trade union policies, and its scorn for stable and permanent unions that would protect and further the immediate interests of its members while propagating for the overthrow of the wage system. As a result these immigrant workers founded unions independent both of the I.W.W. and the A.F. of L., since neither typifies their conception of trade unionism. Their new unions are industrial in form, socialist in philosophy, and devote themselves alike to the immediate and ultimate aspirations of their members. The Amalgamated Textile Workers and the Amalgamated Food Workers are two of these organizations, founded by immigrant workers who received their first schooling in the labor movement from the I.W.W.

Among the recent immigrants several races, particularly the Jews, closely resemble the Germans. While not coming entirely from industrial centers and practicing skilled trades, the Jews came largely from commercial centers, where they had contact with radical political movements. Many of them had practical experience as leaders in these democratically governed propaganda societies. And large numbers of their intellectuals possessed a theoretical and practical knowledge of the world labor movements. Hence, when the Jewish immigrant workers found themselves in unorganized trades and industries in this country, as in the needle trades, they did not long remain a helpless prey of either mercenary fellow countrymen or greedy employers. Like the Germans, they set about to organize their own labor movement with its unions, press, benefit societies, cooperatives and propaganda clubs. Their movement parallels, but at the same time is an integral part of, the American labor movement. Where national unions were in existence the Jewish workers, upon organizing themselves, sought affiliation with the existing unions. Where no national unions existed, or the existing national unions proved unsympathetic, the Jewish workers joined hands with other immigrant groups, the Italians, the Bohemians and others, and developed progressive unions, such as the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, United Cloth Hat and Cap Makers of North America, International Fur Workers Union, and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

These needle trade unions, not infrequently called Jewish unions, are really a composite of a number of southern and eastern European races. Their numerically strongest groups, after the Jews, are the Italians, the Poles, the Bohemians and the Lithuanians. Indeed, within recent years the Italian immigrant workers have manifested as keen and intelligent an insight in the labor movement as the Germans and Jews. Many of the substantial and influential leaders, as well as militant active spirits are Italians. Likewise, the rank and file of Italian workers has also risen to the responsibilities and understanding expected of devoted members of the labor movement. And the other races are rapidly assuming their full share of responsibility in the conduct of the affairs of these unions.

Nor have these needle-trades unions been content with merely imitating the progressive German and English-speaking labor movement. In addition to supporting the progressive policies of unionism, socialism and cooperation, they have been the pioneers in launching and initiating many vital activities.

The needle trades unions were the first to appreciate the significance of workers’ education. The International Ladies Garment Workers and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers particularly support workers’ education on a large scale through their respective educational departments, each manned by a paid staff.

These unions were among the first to appreciate the importance of research and investigation as a basis for effective and intelligent action. The Amalgamated Clothing Workers, for instance, maintains a well organized Research Department, which has done some notable work.

These unions were the first to improve on the old collective bargaining practices by introducing machinery that functions continuously, giving the worker an equal voice with the employer in the administration of the working conditions. This new method is being characterized as the beginning of constitutionalism in industry.

To the needle trades unions also goes the credit of being the first to wage successful campaigns for the 44-hour week.

Now these unions are leading in the attempt to stabilize industry and reduce unemployment to a minimum by unemployment insurance that will be financed by the industry. To the men’s clothing market of Chicago goes the credit for having put this system into practice.

The needle trades unions are at least equaling the efforts of the remainder of the labor movement in organizing labor banks so as to use the financial resources of the workers in controlling credit in the interests of labor. In Chicago and New York there exist banks founded by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union is heading a labor bank in New York which has been established with the cooperation of the Cap Makers and Fur Workers, and some of the other smaller immigrant unions.

Lately, because of greatly improved working conditions, native workers are getting into the needle trades, and these essentially immigrant unions are going through the very interesting experience of organizing the Americans. The fine past record of the unions under our consideration gives promise that they may succeed and master the new situation as they have done many a previous one.

Modern Quarterly began in 1923 by V. F. Calverton. Calverton, born George Goetz (1900–1940), a radical writer, literary critic and publisher. Based in Baltimore, Modern Quarterly was an unaligned socialist discussion magazine, and dominated by its editor. Calverton’s interest in and support for Black liberation opened the pages of MQ to a host of the most important Black writers and debates of the 1920s and 30s, enough to make it an important historic US left journal. In addition, MQ covered sexual topics rarely openly discussed as well as the arts and literature, and had considerable attention from left intellectuals in the 1920s and early 1930s. From 1933 until Calverton’s early death from alcoholism in 1940 Modern Quarterly continued as The Modern Monthly. Increasingly involved in bitter polemics with the Communist Party-aligned writers, Modern Monthly became more overtly ‘Anti-Stalinist’ in the mid-1930s Calverton, very much an iconoclast and often accused of dilettantism, also opposed entry into World War Two which put him and his journal at odds with much of left and progressive thinking of the later 1930s, further leading to the journal’s isolation.

PDF of full issue: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/iau.31858045478306