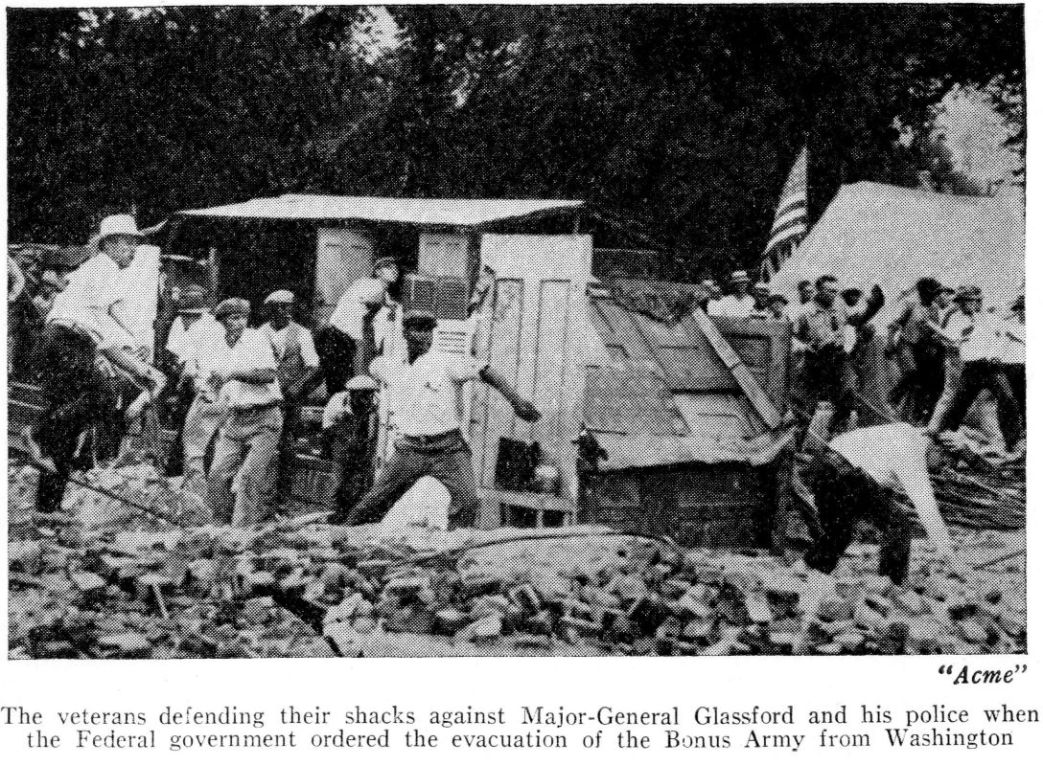

All the talk from the ruling class about ‘our veterans’ is bosh. Soldiers are cannon fodder, the sentimentality attached is purely for show. In 1932, veterans of the First World War marched on Washington D.C. demanding a bonus they were promised.They were shot down by the very army they served in. Joseph North was a witness to the bloody end of that contradictory movement.

‘Hoover Hands Down Bloody Thursday’ by Joseph North from Labor Defender. Vol. 8 No. 9. September, 1932.

(An Eye-witness of the Scenes Described Below)

BEFORE BLOODY THURSDAY

Washington, DC.

You can stand in any given point of Anacostia’s mud-flats and see the gleaming needle- point of Washington’s monument-the capitol dome and the spires of two warships lying in the federal shipyard. The historic frigate Constitution stands off the pier rearing its cross-bars and masts to the sky: its ancient hold newly packed with cases of munitions and rifles stacked to the portholes. Washington is in a state of emergency.

All quiet in Anacostia camp. The veterans sit around or wander in and out of the dug-outs burrowed in the hillside. In this camp there is apparently aimlessness, listlessness under the hot Washington sun-save for a feeble breeze now and then.

A lanky vet with a big Adam’s apple and a trench cap cocked over one ear lies against the hill-bank watching a few clouds in the July sky. A gust of wind and unobserved, he lazily pulls a leaflet from his grimy shirt and flicks it into the breeze. The paper goes dancing a hundred feet down the areaway between the tents. You catch a glimpse of a few black letters in big type: “Rank and file Committee.”

An Anacostia veteran a “Waters’ man” ambling by with a bucket of water eyes it: halts and with a hasty glance to all sides, picks up the leaflet, stuffs it in his pocket.

The lanky vet continues to lie there waiting for more gusts of wind.

A few plug-uglies of Little Mussolini Waters’ 500 M.P.’s walk by, wooden bludgeons in hand, squinting suspiciously in all directions. The vet with the Adam’s apple pulls a few blades of grass from the ground and casually chews on them. The M.P.’s go on. They look what they are. It is not beyond them to club a man suspected of “radical” ideas, into unconsciousness, and throw him into the Anacostia river.

In fact the vigilant rank and filers from the “Red’s” area–at 15th and B Streets, in Washington proper, have wandered into the city morgue and identified several of their men: the bodies bruised, and swollen from drowning.

It’s quiet in Anacostia camp: quiet in the city of Washington. The quietude of the zero hour. When the men go over the top in this offensive at Washington is a question. But it has its inevitable answer.

I sat in camp and watched W.W. Waters cavort. He is leader of the B.E.F. He has now had the name incorporated adding to it the term “Rank and File,” hoping thus to spike the guns of the “radical opposition.” I watched him strut about in his tent–in shiny boots and swagger stick. A modern would-be Ajax ready to do battle with circumstance to ensure a political career for himself. This former cannery boss of Oregon is modest. When he addresses the men from the high wooden platform he falls into gestures of his prototype Mussolini: the upraised hand, the palm outstretched, the swagger, the fingered cane.

I met the vet of the leaflets outside camp a few minutes afterward. We crossed the long bridge into Washington proper. We had met before in the headquarters of the Central Rank and File Committee of the Bonus Marchers. He was up from North Carolina–a Tar Heel.

“What Ah thinks ’bout hit?” He pursed his thin dry lips. “Hit ‘pears to me lak a express train what’s been sidetracked fo’ de time bein’ by de guv’ment men.”

He said what he thought about Waters. “Guv’ment man.” And about Robertson, leader of the contingent that left the day before to “barnstorm” the country. “Guv’ment man. Doak Carter, satellite of Waters and member of the B.E.F. High Command, “Guv’ment man. The world was divided into two classes–“guv’ment men” and the veterans. The scorn he packed in the phrase “guv’ment man”!

This vet was no “Red”–as the Washington Post would have it. He is rank and file. He had been suspected in Waters’ camp of independence of opinion. Rather than be clubbed and thrown into the Anacostia he had taken French leave to join the Rank and File contingent the Sixth area, as it is known.

“Leave Washington?” he scoffed. “Leave for whah? Most we uns hain’t got no home to leave to.”

And he told of his own home near Winston-Salem. “Man,” he said, “When Ah lef home: the wife look at me. ‘She haint et nothin’ but ‘erbs foh three days. She look and say nothin’. But Ah could tell what she mean. She say in her eyes “Git that bonus, man.” Ah look at mah fo’ children. They don’ say nothin’. Just look. And Ah could read in dey eyes. “Git dat bonus, man.”

He laughed short and stopped to look back at Anacostia camp. “Man,” he said, “Mah ‘houn’ dawg follow me on down de street. Dawg don’ say nothin’. But Lawd knows ef’n Ah couldn’t read in his eyes, too—

“Git dat bonus, man.”

BLOODY THURSDAY

Washington, D.C., July 29 The tanks moved down Pennsylvania Avenue as the sky above the capital grew rosy, throwing a reflection over all Washington over the Capitol dome and down the other end of the Avenue to the White House. Anacostia camp was burning. Hoover sitting in the Lincoln room watched the sky crimson. The rattle of the police fire had died down; one veteran lay dead, two dying, 60 critically wounded.

The military, youths in gas masks, advanced with unsheathed bayonets. The veterans, their wives and some with children were driven slowly, stubbornly down Pennsylvania Avenue.

Cavalrymen stationed across the street from the Robertson detachment sat high on horses awaiting the signal to advance.

Robertson’s men; every solitary one of them having refused to follow the ex-circus barker on the “barnstorming” trip away from Washington, stood across the way in bitter knots, watching the soldiery, refusing to step one yard out of the scene of action.

One of Robertson’s men–a stocky, stubble-faced veteran from Southern California, ran into the middle of the street. He stood shaking his first at the cavalrymen who sat like stone images.

“I fought for this country in 1918,” he shouted. “Now they call you out against us. And you come out! For Christ’s sake, are you men or rats?”

One of the horses turned his head toward the veteran; the cavalrymen stubbornly refusing to turn toward the screaming veteran.

“You young punks, it’s kids like you they send out agin’ us. Don’t you know the marines threw down the goddamned guns? They wouldn’t come out agin’ us.

Another horse turned his head. The veteran ran back on the pavement to a flagpole in front of the abandoned building where his detachment was billeted. He jumped high and tore the American flag from the pole. Flag in hand he returned to the middle of the street, threw the flag underfoot and stamped on it.

“This flag,” he cried, “this is the flag I fought for in 1918. Now this is what I think of it.” He danced on the flag; bent over and tore pieces out of it, tearing them into tiny bits.

“See this, you young punks,” he held up handfuls and flung them at the horsemen, “that’s what I think of the flag. If any one of you goddamned yellow bellied punks think different, get off your horse and come on down here and fight.”

The cavalrymen sat there, waiting for orders. They sat looking straight ahead; only the horses turned their heads and eyed the vet in the street. The other men in the detachment joined the lone vet and standing in a long straggly line in the middle of the street, jeered the soldiers; shaking their fists, some of them ripping up other flags, and tossing the pieces cavalry ward.

Hoover sat in the Lincoln study. “With him” the Washington News, Friday, July 29th, wrote, “was Henry M. Robinson of California, capitalist and presidential confidant. The third in the group was Seth Richardson, assistant attorney general. From the windows of the study which knew Abraham Lincoln so intimately, a crimson glow could be seen in the sky to the southeast. The glow gradually spread until the whole sky over Anacostia was red. The bonus camp, first fired by Federal troops, was being reduced to charcoal and its inhabitants driven into the streets of Anacostia at the point of the bayonet under a cloud of tear gas. Shortly afterward, President Hoover left the Lincoln study and the White House announced: “The President has retired for the night.”

The soldiery had advanced in waves: those without gas masks you can see are youths–the majority less than voting age. They had been handpicked by the generals. At Fort Myer the commander had lined the men up. He ordered those who were veterans to fall out of line. All who had seen three years of service or more were ineligible for the coming task. Youths husky kids who had run away from the farm to “see the world”–and youngsters from the city–who had been drilled into robots, who had not yet begun to think it out for them. selves, they were the ones selected for the job.

At 4:22 after William Hushka had been shot through the heart, President Hoover ordered out the troops to put an end to “rioting and defiance of civil authority.”

At 4:45 the troops had come on the scene. The tanks rolled down Pennsylvania Avenue, two machine guns revolving from each turret. The military set in to mop up. The citizenry lined the streets by the thousands. Their boos resound down the avenue: they plead with the military: they move closer.

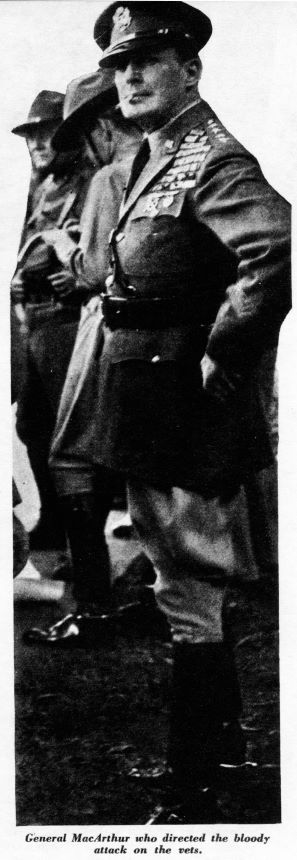

One veteran snatches at the hand of his wife who holds a baby in arms. The figures in helmets stalk straight ahead–their bayonets gleaming before them. Commander MacArthur is on the scene: resplendent in his uniform, a dozen medals sparkling from his chest.

At 4:47 the White House secretary announced that the Secret Service had learned those who led the fighting with the police were “entirely of the Communist element.”

One-half hour later the troops are ordered to “give them the gas.” The tear gas bombs arched through the air, the fuses leaving a white trail in wake. Some veterans run forward, pick up the bomb, and with experienced hand (they had learned the trick in the World War) they toss the bombs back into the advancing ranks. The troops lower their gas masks: they surge forward. Ahead of them prances the cavalry, the sabres swishing through the air.

The groan of the crowd grows: it seems to roll out of the earth. Two children standing at the corner pushed forward by the crowd are slashed across the chest. Hands reach from everywhere to snatch the children, a boy and his eleven-year-old sister, from the horses’ hoofs. The veterans retreat stubbornly: slowly down Pennsylvania Avenue. They fight every inch of the way, those with families caring for them as best they can. Shielding them from the sabres: the horses’ hoofs: the bayonets.

At 5:41 the troops have evacuated the veterans from the Third and Pennsylvania Avenue billet. Then they applied the torch to the shacks: the smoke rolls in heavy dirty waves toward the Veterans’ Bureau of statistics, a dingy, morgue-like structure half a block away.

The troops advance on the other billets at Third and Fourth streets and Maryland and Maine avenues. Here showers of bricks tumble two cavalrymen from their mounts. But the soldiery continue. The torch sets the shacks into blazes. By 7:15 the “radical vets” camp, at Fourteenth and B is attacked. Flames soon remove all traces of the billet. The veterans slowly retreat: carrying their sparse belongings with them. Here a veteran hunched forward bears his mattress on his back, his grip in his hand. There a mother leads her child by the hand, the child looking back. The men strike back: grim-faced, almost silent. The troops advance in strategy: cavalry first, infantry to mop up.

At 9:22 the troops move on Anacostia. Precision: clock-like in steadiness: General MacArthur before them in riding boots and shining medals.

Ten thousand live in this camp: before they have evacuated the troops set fire to several huts near the entrance. A veteran advances waving his shirt: the soldiers eye him.

“There’s women and children there, buddies,” he says to them, quietly. “If there’s a one of them harmed, you’ll have to shoot down the most of 10,000 fighting people.”

The soldiers are silent. A bystander cries out, “Can’t you see these men are your own buddies? You bastards, leave them.” A tear gas bomb arcs its way at the bystander’s foot. Puff, and he steps back uncertainly, his hands at his eyes.

Meanwhile those veterans who had already been evacuated move down the streets–like a migrant people of prehistoric days. The marble of Washington towers at all sides. The Capitol dome gleams: the sky is red.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1932/v08n09-sep-1932-LD.pdf