Louis Bunin, himself an innovator in puppetry, with a look at the ground-breaking Soviet stop-action film that remade the story of Gulliver’s Travels for the era of the proletariat, The New Gulliver directed by Aleksandr Ptushko. Includes a link to the film.

‘The New Gulliver’ by Louis Bunin from New Theatre. Vol. 2 No. 12. December, 1935.

The New Gulliver is in its fourth week at the Cameo as this article goes to press. The film has already been reviewed by every metropolitan paper and magazine that carries cultural and feature news, and the reviewers have elbowed each other in the rush to attain heights of praise. Some of them have even warned Clark Gable and Mickey Mouse to look to their laurels. One said that Gordon Craig was right: “The puppet is an ueber mensch, and the world’s greatest actor.” True, most of them objected to the “underlying propaganda” in New Gulliver’s brilliant technical achievement, but they hinted that Hollywood could correct this defect in future American puppet films. None of the reviewers even suspected that this film carried a profoundly disturbing message to the surprisingly large number of American workers in the puppet field. This article will explain the nature of the disturbance.

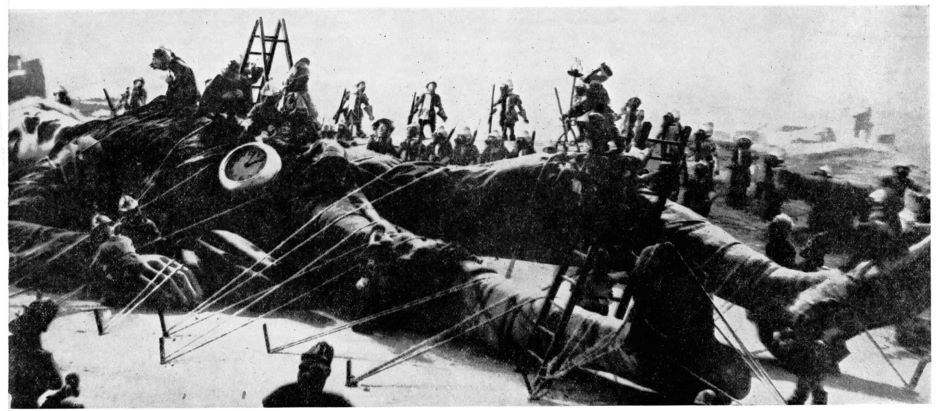

For many hundreds of years, puppets and marionettes have enjoyed a large mass following in all parts of the world. During all those years, puppets have been operated in one of two ways. Hand puppets are placed over the operator’s hands and the movement of the fingers within the puppet gives it life. Marionettes are operated from above by means of strings and controllers. But the New Gulliver has done something tremendously important to Puppet Punch. It injected him with a new and unheard of power and made him fantastically eloquent, flexible and alive. In this film, the puppets are not operated by strings like the string marionettes. Nor are they placed over the hand like the hand puppet. They have no inner mechanisms, no springs or levers.

They are about seven inches tall and are, by themselves, immobile. In America, we call such figures “stand-pats”–but see them on the screen! They sing and laugh; express joy, sorrow, anger, and every emotion desired of a skillful actor. After the hundreds of years of conventional life, puppets have been touched by the magic of the cinema and you would never recognize them.

In America, some puppet and marionette operators had their puppet shows filmed for the screen. After several attempts at using the conventional technique, however, the puppeteers became convinced that an entirely new technique would have to be developed if the puppet were to become a movie star. But puppeteers have never been conspicuous for their wealth. The time and money required for experimentation necessary and materials were obstacles that could have been removed by the movie financiers. However, as all creative artists in America know too well, financiers demand a finished product before they will gamble, and as a consequence puppeteers in America have been left to their own poor resources, hoping that, maybe, some day–

Contrast this with the experience of the collective artists, musicians, writers, puppeteers and craftsmen who created The New Gulliver in the Soviet Union. Obviously, this collective was patted on its back by the government of a great nation and told that time, money and materials were of little moment, if an important and beautiful movie medium could be created. It is precisely this contrast that the American puppeteers, mentioned in the first paragraph, felt so keenly, and were disturbed thereby.

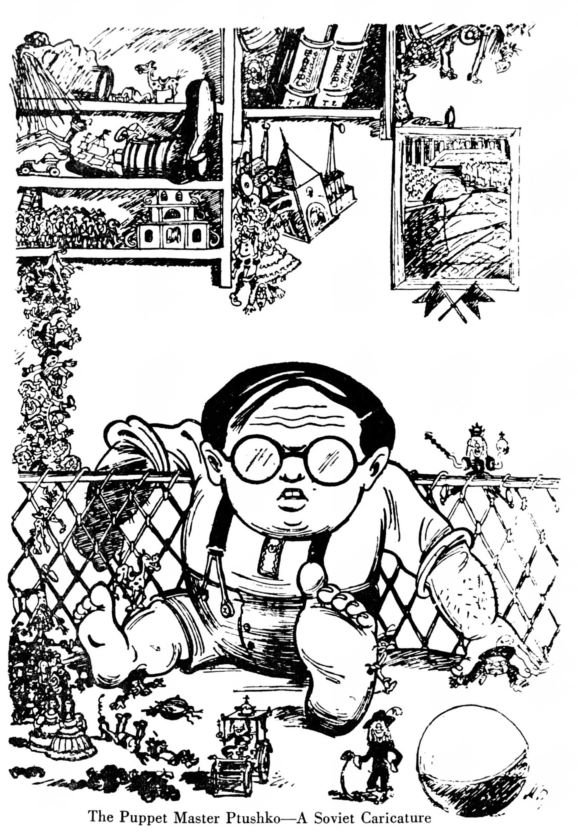

Now let us describe what this collective did to warrant the confidence of the government. The film The New Gulliver was made with thousands of puppets and one human being. The story is based on Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. But by having the young pioneer, Petya, dream that he was Gulliver, the director Ptushko was able to take liberties with Swift’s story and make a perfectly conceived marionette movie. In Petya’s dream, Gulliver sees the land of the Lilliputs through the eyes of a pioneer, and the childish confusion of ancient costume and people with modern machinery is very logical and charming.

The film was twenty-one months in the actual making plus a background of eight years of experimental work. It was made entirely by means of the same technique employed in the animated cartoon and object multiplication. The latter technique involves a tremendous amount of work, but the film proves how worth-while it was. Briefly, with this technique, to make a head change its expression from close-lipped anger to open-mouthed hilarious laughter, one must make from thirty to forty separate little masks; each mask with a slight change of expression, from one extreme to the other. The masks are then photographed on the figure some thirty or forty separate times. When these shots are combined and run off on the screen in the usual rapid sequence, the face seems to change its expression as though it were alive. We can imagine the joy of Sarah Mokil on first seeing the tests, when the hundreds of small separate parts she designed were combined on the screen in these astonishingly alive little people.

To puppeteers in America, the Soviet collective that created the film will be an object of envy and inspiration. Through this collective the screen has finally touched Puppet Punch and miraculously freed him from century-old limitations. This is the only important evolutionary change in the entire course of the life of the world’s oldest actor.

Hollywood, too, will see The New Gulliver. The enthusiastic press reviews will hold forth possible profits to producers. Puppeteers will undoubtedly be called in for consultations and propositions. Perhaps, technical improvements will feature the puppets’ appearance on the American screen, but it is safe to say that the vigor and life in The New Gulliver resulted from the fact that this film took sides in a social struggle, will be lacking in the Hollywood marionette film.

As for you craftsmen and puppeteers I know so well, you who worked in such films as The Lost World and King Kong, and proved beyond a doubt that technical efficiency and ingenuity are obtainable in America; you who were disturbed by the obvious advantages of the Soviet collective must bear the following important fact in mind. There are workers’ film groups in America. Among them are the New Film Alliance, Nykino, and the Film and Photo League. You can bring them your ideas and skill. They will recognize, thanks to The New Gulliver, that an acting company of grotesque, comical, and fascinating little people can win a permanent place in the affections of the great mass of American movie-goers.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

Online video of film: https://youtu.be/CkW8v_qbQbI?feature=shared

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n12-dec-1935-New-Theatre.pdf