Clara Zetkin’s lengthy critique of the Comintern’s new program drafted for 1928’s Sixth World Congress which would usher in the politics of the ‘Third Period.’ It includes a substantial section on the role of women.

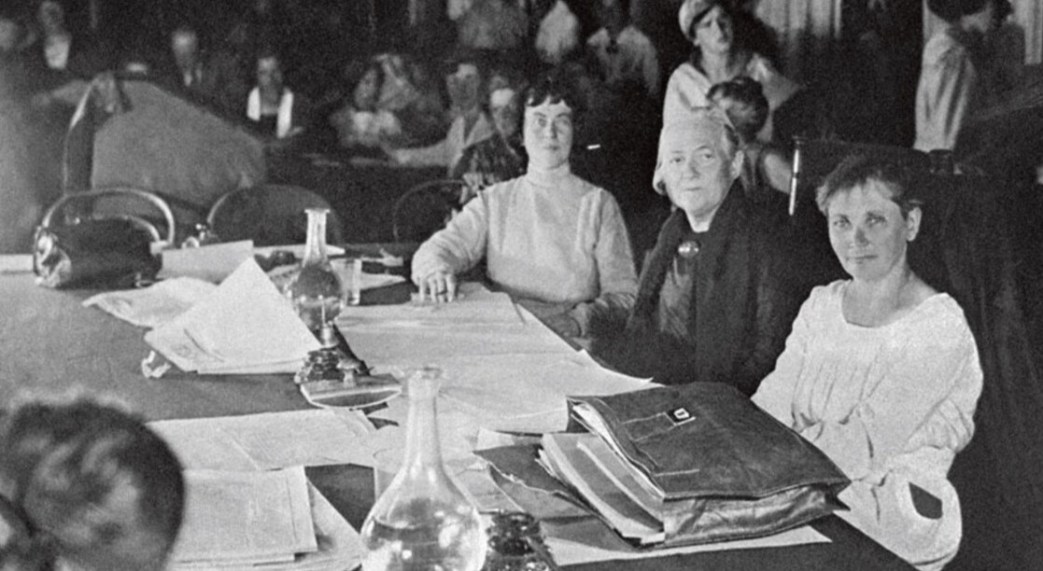

‘Some Critical Remarks on the Draft Programme’ by Clara Zetkin from Communist International. Vol. 5 No. 15. August 1, 1928.

THE mere existence of the Communist International proves the necessity and significance of a uniform, basic programme for all its sections. The Communist International wants to “make history” in the Marx-Engels sense as it should “make” history. Its task is to unite all revolutionary forces of the proletariat, as well as all workers, oppressed classes and peoples in a systematic manner, and to organise them and develop their capacity and desire for action. This requires to be done in order to lead these forces, developed to their utmost, to overthrow world capitalism and realise Communism as the new social order of the world. The Communist International will not, nor should it, allow itself to be driven by the course of historical events; it must constitute a driving force in the midst of the whirlpool of events, certain as to its aims and methods. If this tremendous task is to be fulfilled there must be international uniform guiding principles–true to Lenin’s theory that a good movement must have a good theory–and these principles must be set down in a programme.

“To the Masses!”

In accordance with the aim in view the Programme of the Communist International must satisfy Lenin’s slogan “To the Masses!” It must provide all Communist Parties united in the International with the basic principles of their policy and their entire activity; it must determine the international policy for activity in keeping with the revolutionary awakening and development of the proletariat and the working masses in the struggle for our final goal. This can only be attained, if these masses do not merely consider the Communist Parties as their faithful leaders in the struggle for daily demands, who know and understand their conditions of life and their needs to be free, but also, and above all, as the precursors and pioneers of a new world order (Weltanschauung), a higher social order, free from exploitation and oppression. The urge for this new, higher order, the unerring desire to create it must become a clearly recognised force, which knits the manifold daily struggles closely together and drives us forward stage by stage on a definite path, at the same time lending these struggles determination and significance beyond that of the moment.

Consequently the entire world-regenerating and creative content of Communism must be made clear to the consciousness of the masses and become an unfailing source of strength. Our Programme must serve this purpose by its content and structure. It should not be a compressed, learned compendium of our principles and tactics for comrades, who, thanks to their thorough theoretic training, understand historic development from the point of view of historic materialism. It should rather incite and fit all responsible officials and members of the Communist Parties to explain Communism as a liberating world-conception, as opposed to all the other ideologies, to their brother and sister workers in factories, trade unions and wherever else they may meet. And more than that our Programme must of itself awaken and rally, act as a determining and illuminative force amongst the masses of the proletariat and all classes and social strata, who rebel against the social order in consequence of the rule of trust capital and the decay of bourgeois culture in the imperialist epoch. Our Programme must become the common property of the masses generally.

From this point of view, in my opinion, the Draft Programme of the Communist International, adopted by the Programme Commission of the E.C.C.I., is not quite satisfactory. The text submitted by the Programme. Commission of the E.C.C.I. for examination and criticism seems to me to be not in the manner of a programme in its sections dealing with principles, or a programmatic introduction into the Communist social order and world conception as a whole, but rather a series of leading articles and studies on certain dominant and leading phenomena and problems.

The Programme Criticised

Naturally, it is a mere matter of course that requires no special mention, that in this era of the life and development of capitalism, imperialism, as a prominent decisive historical force, should occupy the chief position in the Communist programme. A profound and far- reaching analysis of the nature of capitalism and of its many-sided economic and social effects would be a necessary premise if our Programme were to provide a sharp and clear-cut definition of the working of the subjective and objective driving forces of social development; driving forces which incessantly and inevitably decide the fall of world capitalism by world revolution, the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the development of Communism as a world social order. The Draft strongly emphasises the fact that imperialism is the highest and last stage of capitalist development, it depicts imperialism as the purest and most developed historical expression of capitalism. But just because this is the case I think that our Programme should deal with imperialism in a correspondingly extensive manner.

Nevertheless, the broad basis of a programme exposition of the nature and effects of capitalism need not be a concise history of capitalism above. But I think it essential that there should be sharply defined and clearly stated definitions both of the economic basis and the ideological superstructure of the bourgeois order which culminates in imperialism. I miss any such definitions in the Draft, I miss an illuminating and concise survey of the economic and social structure of the bourgeois order, a survey which gives a clear characteristic of the different classes and their position, which determines their attitude to the question: Capitalism or Socialism.

Needless to say, the Draft notes the chief classes of the bourgeois order which oppose one another as deadly enemies the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. It establishes their strained relations, which drive the workers on to revolutionary struggles for the seizure of power on an international scale. But it does not penetrate into the historic nature of these relations and their decisive; manifold, economic and social ramifications. The intermediate classes between the two poles in the bourgeois order are only dealt with later; particularly in the sections on “The Strategy and Tactics of the Communist International” and “The Period of Transition from Capitalism to Socialism,” where an analysis is made of the role they could play in the proletarian fight for freedom, and the measures to be taken to win them as allies, or at least to neutralise them. But the Draft makes no analysis of their needs and position as a class, nor does it attempt to explain the contradictions and vacillations between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. In this, as might be expected, the peasantry gets more attention than the urban petty and middle bourgeoisie who with the intellectuals, form a very important section. Yet in highly developed capitalist, industrial countries the urban middle classes will be no less welcome than the peasants as indispensable allies–or maybe dread enemies of the belligerent revolutionary proletariat.

The Draft contains an exposition of the most important and burning problems which the bourgeois order fails to solve, which, on the contrary, imperialism accentuates, extends and multiplies in the course of new developments, thereby showing its complete impotence as a social and cultural factor in reproduction and construction. There is not even a modest reference in the Draft to such phenomena and problems even of a social nature. In my opinion the explanation for this lack is the treatment of imperialism as the dominant political force, especially as regards its destructive and far-reaching effects in foreign policy, which make its economic results retreat into the background and important social events disappear.

The Communist International has had heated debates on rationalisation, but in the Draft this subject is only touched on incidentally. The Draft does not indicate by a single syllable that rationalisation creates new problems and makes old ones more difficult, nor does it deal with the accompanying circumstances which have decisive influence on the working and living conditions of the proletariat. The imperialist era, the highest and last stage of capitalism, is marked by phenomena indicative of an increased and aggravated stage of decline and disintegration in the ideological superstructure of bourgeois society. Copious examples are to be found in science, justice, sanitation, public education, parliament and other organs of the bourgeois state and of public life. Fascism and the reign of terror, for instance, prove clearly that the bourgeoisie, in the struggle against the advancing forces of the proletariat, destroys the legal basis of its own social order. No day passes without its court scandals which corroborate the dishonesty and corruption of bourgeois morality. The bourgeois social order is incapable of banishing the terrifying phantoms: mysticism, pessimism, cynicism, all leave their spiritual imprint.

The Draft Programme does not as much as touch on phenomena of this nature. And yet it is such as these that make the still uninitiated, passive masses realise the common danger of capitalism, and the necessity for its destruction, rather than a straightforward interpretation of the basic laws of capitalist profit-making economy. For social problems serve to awaken class-consciousness in many and spur them on to inquire into the laws that operate blindly in the economic depths. Furthermore, on the basis of private property there are problems and disintegrating phenomena that clearly demonstrate that the bourgeoisie–as Engels said—is on the downward grade of its development, and is steering irretrievably towards its downfall. The picture of the historic situation which leads to world revolution and world Communism is incomplete without a clear interpretation of the decisive facts together with their causes and results. By utilising them in our Programme, confusion, uncertainty and weakness will be brought into the ranks of our enemies and the prospects of proletarian victory strengthened, and consequently, there will be a double advantage. We cannot afford to overlook this.

The shortcomings already mentioned are, in my opinion, responsible for the fact that there is not sufficient emphasis laid on the dynamics of the development, which hastens and guarantees the victory of the proletarian world revolution and the destruction of capitalism during the imperialist epoch. The Draft does not enable the reader to grasp this development by giving a short, plastic exposition of the material and ideological tendencies and phenomena which portend the death knell of the bourgeois social order, the class rule of the bourgeoisie. In the Draft there are far too many ready-made, abstract conceptions, which we Communists know well, but are partially or wholly incomprehensible for the uninitiated masses. Agitational catch-words take the place of the reality that they would understand. Repetition in this respect is no substitute for convincing proofs. The Draft lacks the historic clarity which should serve as a guiding force to awaken and enthuse the masses.

Conditions for the Overthrow of Capitalism

The “Introduction” to the Draft Programme declares: “But the development of imperialism not only creates the material prerequisites for socialism, it simultaneously creates the conditions for the overthrow of capitalism,” This is correct, but it would be better to substitute “completes” for “creates,” for imperialism is the completion of a historic process of development, which leads to the appointed goal. Also in other parts of the Draft the Communist perspective is proved with the assurance that the “material prerequisites for the creation of socialism” develop or exist. But only one kind of prerequisite is provided in the Draft, i.e., the organisational. As regards the conditions for the overthrow of capitalism those who study the Programme ascertain that the insufferable, growing exploitation and enslavement of the proletariat under imperialism cause a constantly, increasing national and international unification, which reaches its apex in the Communist International and its systematic, organised struggle for world Communism. Recognition is given to the increase in the revolutionary strength of the struggling proletariat in capitalist countries, which has been the result of the growth in rebellious outbreaks amongst the colonial and semi-colonial peoples.

The correctness of this line of development cannot be denied. But the statements which are made in the various sections of the Draft provide no clear, compact picture of the material and also of the ideological prerequisites and conditions, both for the conquest of capitalism and the development of socialism. The objective and subjective forces of social development, which inevitably cause both the one and the other, are not represented either in their multiformity or entirety, nor in their full vitality. The Draft Programme’s repeated references to the inherent contradictions within capitalism and imperialism, the uninterrupted rise in the organic composition of capitalism and the consequent fall in profits, which stimulate the quest for super-profits by exploiting the colonies and semi-colonies are but pale and lifeless phrases. The economic, political, social life and action, which these expressions embody remain the secret of the author of the Draft and of all those who know revolutionary Marxism and terminology. But for those masses who are still to be won and led the phrases are foreign and dead; they are as incomprehensible as the revolutionary method and dialectic materialism of Marx and Engels are to the uninitiated. The Draft Programme in this connection presupposes that which the Programme should make the common knowledge of the masses.

Women and the Revolution

I think it extremely important that some of the specially glaring shortcomings in the Draft already criticised should be made good. The Draft pays no attention to the complexity of facts, which, under the rule of imperialism, and especially in conjunction with rationalisation, hasten the destruction of the old-fashioned productive household and transform enormous masses of women from Lilliputian home producers to producers on a modern scale in big factories. This process of transformation is of tremendous consequence and constitutes a revolutionary factor of first-class importance. It creates the economic basis for the social equality of the sexes both in law and practice, for the complete social and human liberation of woman, for the abolition of marriage for money or other advantage, the dissolution of family property, the recognition of motherhood as a social service and the obligation of society to care and educate children and the young. And last but not least amongst the colonial and semi-colonial peoples the tortuous disintegration of domestic production and the family by the predatory claws of capitalism has a revolutionary effect, especially in breaking up ancient beliefs which reduced women to the level of domestic animals.

The tablets are crumbling on which are inscribed the “Thou shalts” about the social and sex relations between the sexes and the relations between parents and children. The most disgusting domestic conditions, conditions, family tragedies, prostitution, orgies and excesses protected by hypocritic bourgeois honesty, infantile mortality, appallingly large numbers of waifs and strays, and juvenile crimes cry out in capitalist countries for new social rules of life. The tendencies to introduce marriage and sex reforms, the fight for legal abortion, the decline in the birth rate and the rapid spread of the “birth control” movement, in other words neo-Malthusianism, are an eloquent language in themselves. Of no less importance are the endeavours to introduce fundamental educational reforms as regards method, character and goal. In all capitalist countries, and even in the East, organised masses of women are carrying on a struggle for equal rights with men. The army of proletarian women, women workers, who are fighting jointly with their class comrades in all economic and political struggles, is becoming more numerous and more certain of its goal. In China the women workers and peasants participate in the revolutionary movement.

What an instructive contrast to the attitude of the bourgeois social order is provided by the construction of the socialist state of proletarian dictatorship which faces all these phenomena and problems. In one the effort to hold on to the past, to preserve what is rotten and decayed, so that the power of dead property over living beings is portrayed as “the law of the family”; and unavoidable concessions for the protection of mothers and children’s education are carried out as though they were being handed out alms. In bourgeois democratic countries women’s suffrage in face of open and covert opposition is working for the actual realisation of the formal equality of women. In the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, on the other hand, there is the honest endeavour of the Soviet power to realise to the full throughout the entire country the legal right of women in all fields of social activity. In the fight with cultural backwardness and poverty numerous social institutions are being established and perfected, which relieve women from much domestic labour and facilitate their maternal duties There is a passionate seeking for new forms for the union between man and woman in order to establish a new legal system, which will ensure the liberty of the individual, whilst observing social bonds and responsibilities.

The Draft Programme does not breathe the slightest word about all this fermenting and to a certain extent chaotic life, which affects millions and often interferes in a much more destructive way with the personal life of the individual than many other events in the course of historical development. There is no doubt that both in the Soviet Union and outside it–for in this field too the Soviet Union serves as the great historical experimental field of world Communism–external and internal contradictions of development are in wild disorder, and that this period is far from ended. But is that not also the case in many other fields of social activity about which the Draft comes to theoretical and practical conclusions? In my opinion a Communist Programme should not omit stating its attitude to the revolutionary processes here referred to; it should make a cool and daring statement by the application of the revolutionary methods of dialectic materialism of what degrades and of what advances, or what is direction and goal in the tendencies of development in which natural and cultivated tendencies are closely interwoven. The revolutionary youth of all countries is waiting impatiently for the Communist International to make a statement on these points, so that it may gain clarity and guidance for its conduct of life. The educational advisers and friends of this youth also feel the necessity for such a statement in the Programme.

Conventional Phrases

The Draft Programme restricts itself to a few conventional phrases about the equality of women and propaganda amongst them, leaving untouched this very extensive, intricate and difficult complexity of questions here enumerated. It does not even mention what is immediately practical and undisputed. That is to say the extraordinarily great importance to be attached to the participation of masses of women in the revolutionary class struggles of the proletariat, and what is more important, their cooperation in the socialist work of construction for the development of world Communism. The very appearance of women on the battlefield of the class struggle constitutes in itself a tremendous piece of revolution. The Draft Programme, that completely ignores all this, was written on the ground that has already absorbed the blood of so many women in order that it might become the realm of proletarian dictatorship and of socialist construction. There is no mention made of the exemplary sacrifices and bravery of women in the struggle, their untiring devotion to the work of the Soviets in all organisations and social institutions in order to transform the Soviet State into a Communist social order.

The demands which Communists make for the period of struggle, for the conquest of power and for the transition stage from capitalism to socialism do not contain a single one on behalf of women. No demand is made for full civil rights, nor for the welfare of mothers and children. In the section dealing with “Strategy and Tactics” the systematic activity of Communist Parties for the training of the revolutionary masses of women is restricted to women workers and peasants. Statistics show that even in highly industrialised countries women manual workers constitute a minority of women proletarians, and that in practically all capitalist States, in industries of decisive importance for the conquest of power–mining, metal trade, railways–the number of women manual workers is very small. Experience has shown that women workers in these and other industries are the bravest collaborators of men in the struggle, that they often have decisive influence on the course and outcome of strikes and agitations. A classic example of this was the heroism of the women during the General Strike and the miners’ struggle in England. Why should workers’ wives and petty bourgeois women be excluded from the army of the world revolution, since the Draft Programme has recognised the necessity of recruiting both the peasantry and the urban petty bourgeoisie as allies? Furthermore, in extending the battle front against imperialism attention must be paid to the increase in the number of women employees as compared with that of women manual workers as a result of rationalisation. Statistics for Germany and the United States of America prove this fact, which cannot be ignored by the industrial proletariat when mobilising for the struggle for victory.

The chief principle for the systematic activity of Communist Parties amongst proletarian women as a whole, amongst women workers of all kinds, must be the greatest possible extension of the battle front against imperialism and of the working front for the establishment of socialism and in conjunction with this extension increase of activity. Our Programme must realise that the collaboration of the broad masses of women does not only mean the increase in the number of the revolutionary forces, but also the improvement in the quality. Woman is not only an unsuccessful copy of man, as a female being she possesses her special characteristics and value for struggle and construction, and the free development of long chained-up energy will help on the struggle and the work of construction. Therefore I miss from the section in the Draft “The Ultimate Aim of the Communist International,” not only the statement, that together with abolition of private property the industrial and social differences between the sexes and generations will also disappear as well as other effects of private property; but in a still greater degree I miss the stress that should be laid on the enrichment that will ensue in the culture of world Communism. Another gap in the Draft in this connection. There is no mention made of the importance for the versatility and the rich resources of culture in the Communist human family of the inclusion of the hundreds of millions of Eastern peoples–and together with them the women of the East–whose talents and capacities, oppressed through all the ages, will have freedom to develop and will be contributed to the general good.

The “Intellectuals”

The remarks about the “Intellectuals” are not, in my opinion, in keeping either with their position as a class, so full of contradictions and conflicts, or with their far-reaching importance as allies in the struggle of the proletariat, especially in the general transition to Communism. No thought is given to the varied necessities of learned men, technicians, artists, writers, teachers, officials, although therein is actually to be found the lack of liberty and the necessities imposed on science, art, national education and of culture itself by the bourgeois social order. The Draft contains no special slogans on behalf of the intellectuals beyond the general demands for education and culture. It affirms that the “intellectual technical forces” hang on the survivals of the bourgeois order, and that the proletariat, besides suppressing in an energetic manner all counter-revolutionary activities, must not lose sight of the necessity of attracting these qualified social forces to the work of socialist construction. The proletariat attempts to attract the intellectual, technical forces, to bring them under its influence and to secure their close collaboration in revolutionising society. In another place the demand is made for the extension of the influence of the Communist Parties to the lower strata of the intellectuals.

There can be no difference of opinion as to the necessity of recruiting the lower strata of the intellectuals for the struggle and work of construction of the revolutionary proletariat; by these are meant those intellectuals that have become proletarianised, or are on the brink of the proletarian class, who are separated from the workers only by the social status of their occupation and their bourgeois outlook. But, in my opinion, our recruiting should not be limited to the lower strata of the intellectuals. Such a conception is a variable, vacillating quantity, and besides there are frequently intellectuals to be found who are filled with enthusiasm for the Communist ideal and rebel against capitalists. Revolutionary thought and the desire to fight in individuals, despite class position, is not always bound up with property and income. And then why recruit only “technical intellectual forces” for the realisation of socialism? Does not this great goal require the conscious and free co-operation of scientific research workers and teachers, doctors, lawyers, teachers, artists, constructive and educative forces of all sorts? The proletariat has urgent need of the co-operation of the intellectuals in the difficult task of the socialist education of the middle and small peasantry, the raising of the standard of the toiling masses by the cultural revolution, the crystallisation of a firm, clear, far-reaching and at the same time purely Communistic world conception, and the victory over all bourgeois ideologies and their reformist variations. Philosophers, poets and other intellectuals were amongst the bravest and most successful fighters amongst the former revolutionary bourgeoisie in the battle against feudalism, and created the ideology of the new ruling class. Imperialism especially must thank the intellectuals that the idea of the greater fatherland” took hold of the masses and drove them into the World War. The intellectuals were in all countries the preachers of “the fight to a finish.” Teachers, doctors, agronomists–to mention just these three classes–neutralise the power of the clergy in villages and small towns and also the activities of other counter-revolutionaries. In this connection I wish to make a few parenthetical remarks. The declaration that religious ideology must be overcome is to be welcomed. But the form does not seem to me to be in keeping with the heights of historic materialism and the historical significance of religions in the life of the people; it borders on bourgeois free-thinking. In the demands for period of struggle and construction the state reorganisation of public health is omitted. It is the pillar of “human politics,” just as national education and labour protection are the pillars of the revolutionary proletariat in the State of the proletarian dictatorship.

The Draft Programme contains sections which I think require to be put more clearly, or to have explanatory notes if they are to avoid misinterpretation. For example: the phrase which says that the Communist International signifies a new principle for the organisation of the masses will make the uninitiated ask, What is this new principle? The expression about the one-time uniform world economy is correct in so far as there was no state until the 1917 revolution in which production was based on socialist principles. But there have always been, and there still exist within the framework of the capitalist method of production in world economy a considerable measure of pre-capitalist methods of production, feudal methods which capitalism opposed. The phrase, “The hierarchy established by the division of labour and with it the antagonism between physical and intellectual labour will be abolished” would be improved by readjustment. In my opinion, the abolition of this antagonism has other reasons besides the disappearance of the hierarchy established by the division of labour.

Imperialism and the Revolution

The Draft stresses the fact that “Unevenness of capitalist development becomes still more accentuated and intensified in the epoch of imperialism,” and also “the uneven development of its various parts is reflected in the uneven development of the revolution in separate countries.” To this should be added that it expresses the dialectic of history, that imperialism simultaneously cancels this unevenness–which is a prerequisite of its existence–increasing to the utmost the contradictions between capitalist classes in the various countries and, on the other hand, in spite of all the differences pointed out, it unites the proletariat nationally and internationally, brings over to its support colonial and semi-colonial peoples and drives the oppressed and exploited of the whole world on to the path of revolution. Germany is counted amongst the highly developed capitalist countries, with powerfully developed productive forces and highly centralised production, still it cannot boast of an old bourgeois-democratic regime. Up to November, 1918, the prevailing regime in this country was, to quote Bismarck, “absolutism in undress,” and now at the head of the German Republic the declared monarchist Hindenburg reigns as President with very far-reaching, undemocratic powers.

Quite apart from the greatest estimation of the unique historical importance of the proletarian dictatorship in the Soviet Union I consider the phrase vulnerable which points out that the proletarian dictatorship of the U.S.S.R. forms the main force of the international socialist revolution–the basis of its development. The main force of the process of the further development of the world revolution in the present capitalist countries consists in the strength and ripeness of the objective and subjective forces in those countries. The existence of the proletarian dictatorship in the U.S.S.R. has a powerful influence on their effect and creative activity. Therefore this sentence would be better if put thus: The proletarian dictatorship in the Soviet Union is one of the most important decisive driving forces for the advancing international socialist revolution, it is its vanguard and its best support in the process of its development. The praise meted out to the international proletariat by stating that its support helped its brothers and sisters in the Soviet Republic to withstand the armed attack of the internal and foreign counter-revolution is undeserved. The heroism of the Russian proletariat and peasants, strengthened by their belief in the support of the international proletariat, alone was responsible for this miracle; it is a debt of honour on the part of the workers in capitalist countries to wage a ruthless struggle against the imperialist desires to throttle the U.S.S.R. The construction, the ramifications and the functions of the Soviets should be treated in greater detail.

Tactics of the Transition Period

The tremendous importance of the agrarian revolution in the colonial and semi-colonial countries should be made absolutely clear by a characterisation of their economic and social structure. The “betrayal” of the national revolution by the bourgeoisie in these countries should be explained from the class point of view. The enthusiasm and fidelity of the bourgeoisie for national independence, the fatherland, had everywhere their special reasons, and were always connected with very tangible class interests as exploiters or rulers; the value of these ideals rises and falls with the benefit to be reaped. The bourgeoisie in the colonial and semi-colonial countries prefers to capitulate before imperialism and become its ally, than to capitulate to the revolution and the liberation of the toiling masses which it exploits. The bourgeoisie “betrays” its national ideology in order to preserve its class rule of property. In my opinion our Programme should state this, and thereby it would not only contribute to a better understanding of events in colonial and semi-colonial countries, but also help to destroy the social-imperialist legend of the reformists about the joint fatherland of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

The Draft Programme is very eloquent in the exposition of the transition period from capitalism to socialism; it enumerates a comprehensive number of measures which the victorious proletariat should carry out by means of the dictatorship in the various countries. It is a platitudinous matter, of course, that the proletariat of all countries will weigh the positive and negative experiences of the great socialist work of construction in the Soviet Union in the transition period to socialism. I feel that this unavoidable homage in the Draft has caused a certain automatic repetition of the measures to be taken. But historical developments in the various countries will necessitate many a deviation from the course indicated, deviations which will be permissible only in so far as they are in keeping with the basic goal.

Just one other point. Why does the Programme specify the seven-hour day as the goal, and what is the justification for deciding on the eight-hour day for colonial and semi-colonial people? The decision as to the normal working day seems rather petty when compared with the great revolutionary measures for the expropriation of the expropriators, for this can possibly be decided during the class struggle before the dictatorship of the proletariat. Besides, there is the possibility that in defence of the Soviet State and its socialist construction it may be necessary to prolong the working day for certain groups, or for the proletariat generally. I think it more important and more in keeping with the great change to be accomplished that workers be ensured the legal right to determine working hours, wages and all the conditions of labour through their workers’ councils in conjunction with representatives from trade unions and the economic organs of the Soviet State.

Strategy and Tactics

The section “Strategy and Tactics of the Communist International” should take precedence of the section dealing with the transition period, for it has to do with the struggle for the conquest of power. This takes precedence over the period of the actual exercise of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. The seizure of power is the next stage to be reached; it is the most pressing task of the moment, and no time should be lost in carrying it out by any unnecessary negotiations. The transposition of these sections is also justified by the fact that the measures taken for the conquest of power should prepare those of the transition to socialism. In addition to foreign political conditions the results of the struggle for power will determine the manner of dealing with the problem of war, Communism and N.E.P.

I think the ideological and organisational nature of the Communist Parties should be more sharply defined. Especially their relation to the trade unions as sections of the general revolutionary Labour movement, which should be under the leadership of the Communist Party as the supreme representative of the proletariat. Amongst the reformist organisations and masses the idea still prevails that trade unions should be “neutral,’ “non-political,” independent of the revolutionary class party and its leadership. There are also the traditions of trade unionism in Great Britain, syndicalism in France, the subjection of the German Social-Democrats to the commands of the General Commission of Trade Unions–this fatal victory of reformism in Germany. Furthermore, it would be of consequence to adopt a dcisive attitude towards the special functions which the trade unions should fulfil on the basis of capitalist society. This would help to overcome the influence of the reformist trade union bureaucracy.

The conclusion of the Programme should be: “The Ultimate Aim of the Communist International–World Communism.” This section could do with a more highly coloured exposition without any tendency to utopian pictures of mere details. I also consider it necessary that the Programme should contain a compendium of the scattered arguments against reformism and social-democracy. The scattered nature of these arguments disturbs and dims the basic line of the Draft Programme, and by superfluous repetition undermines the force of these arguments. These arguments include the critical characterisation of “Constructive Socialism” and the insignificant Guild socialist tendency. Both of these are varieties of reformism. The statements about “anarchism” and “revolutionary syndicalism” might also be included in this section, for in spite of all their revolutionary talk their activity has a similar effect the splitting of the forces of the revolutionary proletariat. The point might be raised as to whether all these arguments about all the non-Communist organisations and sects would not be better in a special section with a title something like: “The splitters and wreckers of the revolutionary Labour movement.”

In concluding my article I should like to make some critical suggestions in respect to the arguments against reformism in the Draft. The leitmotif of these arguments begins already in the “Introduction” with the betrayal of the social-democratic leaders, and the systematic bribery and corruption of the Labour aristocracy with the assistance of the extra profits gained by the bourgeoisie in colonial countries as the cause of the split in the ranks of the proletariat and the defeats suffered by its revolutionary vanguard. The statement about the betrayal of the social-democratic leaders is correct, and no term is too strong for their condemnation. It is also an incontestable fact that the bourgeoisie corrupts the Labour aristocracy. We must ultilise both of these facts and impress them on the consciousness of the masses. Still we must not deceive ourselves about the betrayal of the reformists and the corruption of the Labour aristocracy which only constitute the partial truth in answer to the question as to the causes of the defeats of the proletarian revolution and the temporary relative stabilisation of capitalism. The painful supplementary explanation must be made that in the most highly developed capitalist countries the great majority of the proletariat is still in the reformist camp and not in the revolutionary ranks.

The contradictions of imperialism include the advancement both of the national and international organisation of the proletariat and also its national and international disintegration. The first imperialist war was a powerful proof of this, and the post-war period is in no way inferior to it. Imperialism splits the proletariat as a class, not only by the bribery and corruption of the Labour aristocracy, and a large section of its political and trade union leaders, who have a big responsibility for the split, but also splits the workers nationally and internationally to their very depths by strengthening the illusion amongst the masses that they too can benefit by the bourgeois social order. The majority of the workers in the United States under Gompers rejected the revolutionary class struggle at a time when the country was in receipt of European capital, and there were as yet no colonial extra profits for bribes. In Germany the great majority of the proletariat decides for the coalition with the bourgeoisie, and not with the Workers’ and Peasants’ Government, even after nine years of accumulated misery, during which there can be no question even of the crumbs of colonial extra profits. The Communist Party was not lacking in its zealous exposure of the betrayers and corrupt elements, who themselves gave the game away by their inactivity and the bourgeois nature of their policy of sacrificing the interests of the proletariat. And yet the great majority of the proletarian masses rally to the black-red-gold banner of reformism. The last elections in Germany were a clear proof; in this respect they were typical of the international situation.

Our Programme as a Weapon of Struggle

Let us admit that in the various countries the weakness of the still young Communist Parties, the errors and shortcomings of their policy and leadership have delayed the adherence of the proletarian masses to the revolutionary ranks. But this, too, is only a partial truth from which we shall undoubtedly learn, but which does not cover the whole ground. The decisive factor in the attitude of the majority of the workers is that they are still ruled by reformist convictions. The masses of the proletariat, of the workers, hope and wait for the formal democracy of the bourgeois order, and its promised gifts; they fear the revolution and its sacrifice. They have more confidence in the bourgeois alliance with the class enemy than in their own revolutionary strength. The chief task of Communism lies in destroying the paralysing, enslaving mass adherence to democracy; the masses must be raised from reformists to revolutionaries. In a hand-to-hand struggle with the enemy, world conception against world conception on the one hand reformism, on the other Communism.

The significance of the Programme of the Communist International in this struggle is apparent. The Programme must be a mine of historical knowledge, which gives strength to pursue the path through the manifold complexity of daily events, which links up millions in the steadfast desire to march onwards to revolution! From this standpoint the Draft must fill up certain gaps and be more sharply defined theoretically. Of course, there should be no mercy shown to the crimes of the reformists and the Second International. This denunciation should be accompanied by a clear and thorough exposition of the main theories of the reformists with which they deceive and hoodwink the masses. Not only should the illusion about the democratic republic and the Utopia of ultra-imperialism be absolutely smashed, but also the foolish drivel about “the idea of the State,” which subordinates the class interests of the proletariat, the fable about “economic democracy,” that old Bernstein revisionist drug that Hilferding unearthed, which claims that the supremacy of the employer is to be overcome, without the revolutionary class struggle, by means of peaceful trade union policy, social reforms and ten-pound shares and all the rest of it. Our Programme must be a model both in content and form for our campaign for the masses of toilers, for the solution of our twofold task: to win over these masses once and for all from the reformists and unite them with the Communist Parties in a red united front, not for the struggle for daily demands, but for the struggle and victory of the revolution.

The Draft which will fulfil these demands will constitute a broad basis for a Communist Programme. I am convinced that our Programme after careful revision by a commission of leading theoreticians and practical workers should be submitted to all sections of the Communist International for a thorough public discussion. Such a discussion will be a fruitful method of securing inspiration from the fulness of social life and activity, which Lenin so often praised as an inexhaustible educative source. It will help to establish clarity and certainty in the national sections on theory and practice. It will accomplish necessary and good educative work amongst Party members, and in addition amongst the masses who have not yet been recruited. The collaboration of the masses in the work of drawing up our Programme will constitute a part of the work of liberating the working class, which must be the business of the workers themselves.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-5/v05-n15-aug-01-1928-CI-grn-riaz.pdf